Many years ago I was working two jobs to save to go overseas. One of these two jobs was an early morning shift in a coffee cart, just off Courtenay Place in Wellington, outside a building that housed corporates of many kinds. I worked at the coffee at cart with Jenny, who became a good friend.

Jenny was everything I thought going overseas would make me: effortless artistic, politically informed, culturally savvy. Her parents were both artists, and her uncle was once a Labour Prime Minister. Unlike me, she didn’t need to go overseas; she already knew about the world. In fact, when I told her I was saving to go to India, she just shrugged and said, sweet. No bravado, no interest in impressing. The opposite to me.

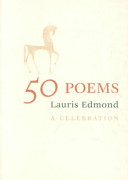

Jenny knew I was interested in poetry and that I’d been trying to write for a while. She knew I’d been reading people like Simone de Beauviour and Anaïs Nin, and that I carried this deep-seated belief that real life happened beyond these shores. Probably in France in the 1960s, but that didn’t stop me from going in search of it. Instead of challenging me on this warped idea, she simply slipped a beautiful cream paperback into my hands the day before I set sail; a parting gift. The book was 50 Poems: A Celebration, by Lauris Edmond. As if to say, there might just be some life here too.

I took Edmond with me in my rucksack, and together we would travel through India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and later, onto the UK, where I met up with Jenny in Glasgow some years later. I never said anything to Jenny, but even now, twenty or so years later, as I write this from my home in Dunedin, I still think about that parting gift and what it taught me.

There are several poems from this book that I have continued to come back to over the years. Including this one:

Epiphany

for Bruce Mason

I saw a woman singing in a car

opening her mouth as wide as the sky,

cigarette burning down in her hand

– even the lights didn’t interrupt her

though that’s how I know the car

was high-toned cream, and sleek:

it is harder for a rich woman…

Of course the world went on

fucking itself up just the same –

and I hate the very idea of stabbing at

poems as though they are flatfish,

but how can you ignore a perfect lyric

in a navy blue blouse, carolling away

as though it’s got two minutes

out of the whole of eternity, just

to the corner of Wakefield Street –

which after all is a very long life

for pure ecstasy to be given.

Lauris Edmond

Who was Bruce Mason, and why was Lauris Edmond writing a poem for him? More importantly, who was Lauris Edmond, and how could she write a poem that had the lines “the world went on/fucking itself up just the same,” in such close proximity to “Wakefield Street”? In my extraordinary naïvety, this poem took me by the hand and said: see, there are people here that think. Here was the poet, looking and noticing, thinking carefully, trying to understand, playing, slowing reality down a little … There was a form of existential enquiry happening in New Zealand, right under my nose — I’d just been too ignorant and ill-informed (and religiously adhering to a stereotype) to take notice. Which seems to me the whole point of the poem — there is stuff happening right in front of us all the time, we’re just too egotistic or preoccupied to see or hear it.

Lynley Edmeades

‘Epiphany’ is from 50 Poems: A Celebration (Bridget William Books, 1999) and was originally published in New & Selected Poems (Oxford University Press, 1991) and is posted with kind permission from the Lauris Edmond Estate.

Lauris Edmond (1924-2000) completed an MA in English Literature with First Class Honours at Victoria University. She wrote poetry, novels, short stories, stage plays, autobiography and edited several books, including ARD Fairburn letters. She received multiple awards including the Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship (1981), an OBE for Services to Poetry and Literature (1986) and an Honorary DLitt from Massey University (1988). Edmond was a founder of New Zealand Books. The Lauris Edmond Memorial Award was established in her name. Her daughter, Frances Edmond, and poet, Sue Fitchett, published Night Burns with a White Fire: The Essential Lauris Edmond, a selection of her poems, in 2017.

Lynley Edmeades is the author of As the Verb Tenses (Otago University Press, 2016), and her second poetry collection, Listening In, will be published in September this year (with Otago University Press). She is also a scholar and essayist, and currently teaches on the English program at the University of Otago. Her writing has been published widely, in NZ, the US, the UK and Australia.