Photo credit: Time Out Bookstore

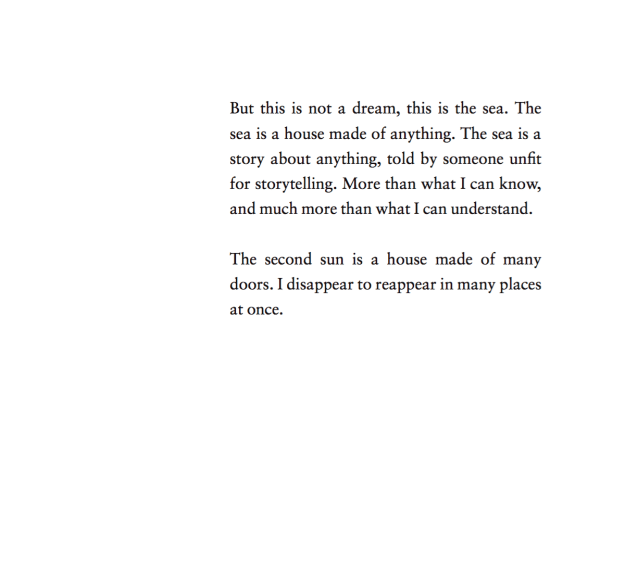

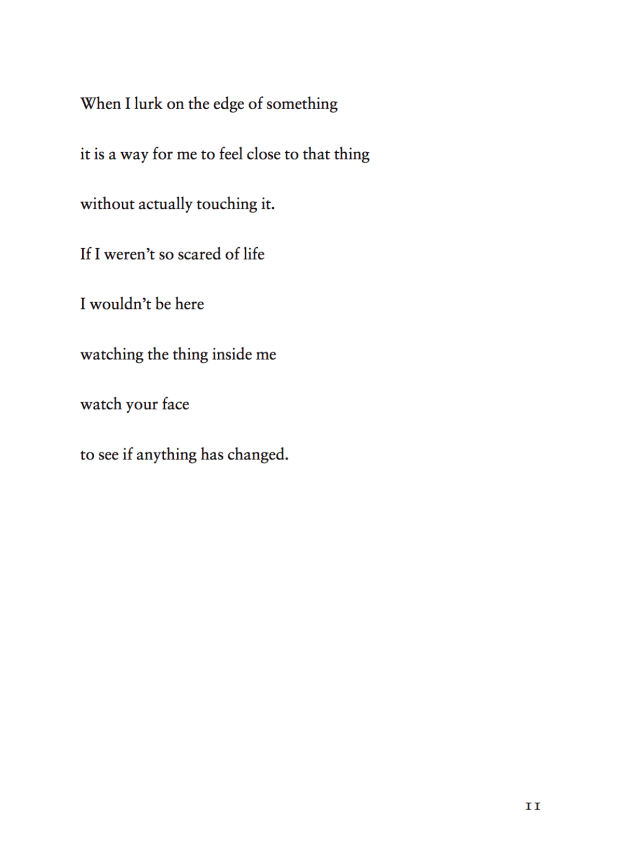

Gregory Kan’s poetry has featured in various literary journals including Atalanta Review, Cordite, Jacket, Landfall, The Listener and Sport, in the annual Best New Zealand Poems, and in art exhibitions, journals and catalogues. His debut collection, This Paper Boat (Auckland University Press, 2016) was shortlisted for the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. His new collection, Under Glass, has gripped me as much as his debut. While his first book was unified by themes – he contemplated the poet Robin Hyde, his family, ghosts – Under Glass is also unified by form. A dialogue develops between a sequence of prose poems and a sequence of verse poems. The former features a protagonist moving through a strange and at times estranging landscape with its blazing sun. The latter establishes an interior landscape where the speaker struggles to make sense of things in a glorious interplay of gaps, knots, silence, physical things, ideas, yearnings, dream, hinges, contact, light, dark. The title underlines the way everything trembles and meaning is both prolific and unstable. The glass is a barrier, a way through, transparent, a longing to see, breakable, dangerous, a distortion, a view finder. I loved this book, this poetry haunting, and set about an email conversation with Gregory over nine weeks with pleasure.

Gregory Kan, Under Glass, Auckland University Press, 2019

Paula: Your new book is beautiful, mysterious and haunting, I really like the idea of skirting its edges rather than breaking through the ‘glass door’ of its making. What psychological, physical and heart states did its writing place upon you?

Gregory: Writing the book was a process of discovery from start to finish. For me, writing poetry involves a set of transactions or exchanges with the unknown. It is a fragile but ecstatic space to inhabit. I was privileged enough to be on the Grimshaw-Sargeson Fellowship when I wrote the bulk of it. I bounced a lot between our place in Wellington and the Sargeson Centre in Auckland. Perhaps that complemented the liminal, the interstitial states that come to characterise a good portion of my work: in-between, incomplete, on-the-edge-of, peripheral, fragmentary, perforated with holes. Radically finite. Distant but not disconnected. The Sargeson Centre is a beautiful but haunting place in and of itself. There’s a long bookcase in the apartment lined with portrait photos of all the previous fellows. At night there is nobody around except for passers-by and the occasional reveller in Albert Park. Ghosts everywhere. There is sometimes nothing more haunting than the process of writing, and the artefacts of writing. The overwhelming sense of the past in the present meant that my sense of linear time dissolved severely. I went looking for things to see if I could escape them.

Paula: Hmm. I wonder if all writer’s residences are like this? I had a similar experience at the Robert Lord cottage in Dunedin.

As I read the various hauntings in your collection three motifs stood out: the map, the mouth, the maze: ‘I started marking the walls with my knife / so I’d know where I’d been.’

The reading of the poetry took me into a maze of sea, land and self. I got ‘lost’ in reading. And that was a joy. The unconventional ‘maps’ were the navigational points. I am reminded of the blurb on Hinemoana Baker’s book, waha | mouth: ‘I’d like to think that opening this book to read is like standing at the mouth of a cave, or a river, or a grave, with a candle in your hand.’ So much for skirting the edges! Here I am drawing in close on a stanza like this:

Today the world overwhelms me.

I feel a garden

growing in my mouth

and eventually touch stone.

I am afraid of appearing sentimental about sentimental things.

Was the mouth also important as you wrote? Along with the maze and the map?

Gregory: Thanks for sharing that image from Hinemoana Baker’s book/blurb. I love it. Yes, I suppose the mouth marks several interrelated ideas for me: gap/hole/gate, threshold/limit, transition/passage, entry vs. exit, inside vs. outside, private vs. public, and a lot more. Someone, I can’t remember who, writes about the mouth being a place where the soft inside opens up to meet the outside. At the same time, I should qualify that this wasn’t part of any conscious or conceptual intent when I was writing the book. It’s something that I can see in hindsight. On the other hand, the map and the labyrinth were both entities I was conscious of letting loose in the strange game of writing the book. In retrospect, I think of all these entities constitute the problem-space of finite agents, with finite resources and knowledge, trying to understand a volatile and alien world.

It’s always fascinating to me, the differences between what one anticipates, speculates and discovers, when writing. I look forward to hearing about what other people notice when they read the book!

You think I don’t know you anymore

and I never read your emails

but I wonder if we have the same nightmare

about some final thing

for which there is no forgiveness.

Paula: I think the movement between the unconscious and conscious that a poet leaves in a poem contributes to the way a poem is both fertile and open. And that is exactly why Under Glass is a joy to read; mysterious yes, musical yes, multilayered yes. The movement is also heightened by the open pronouns. Who speaks? Who is playing? Who hides? In your last collection you engaged in self-revelations by way of Robin Hyde. Do you do so here by way of ambiguous pronouns? Or are the speaking characters both porous and invented?

Gregory: Yes, the “I” and “you” in the book are varying mixtures of real, imagined and abstract. I’ve been interested in the fragility of the address and of the self for a long time.

Both the “I” and “you” in the book are fluctuating identities. Some of the poems involve addressing real individuals in my life to begin with, but then depart from them. Sometimes they are completely abstract and/or imaginary addressees. The “I” also shifts within and from each poem. In all these ways (and many others besides), there is an intense fragility to the transmission of information and intent. I wanted to challenge the transparency of the lyric poem and the lyric “I” and “you” in this particular way. I wanted to push it to a kind of limit, to de-privatize the self. I wanted something both incredibly personal and incredibly abstract.

Paula: Such movement, such uncertainty, fluctuations, flickers. Reading this has sent me back to the book to follow those tremors. Conversely, do you think a poem or a line or even a word can offer a temporary but comfort-rich anchor? For me: ‘Every day the coast looks the same, as/ though I haven’t moved’.

Gregory: In order to write, I need to believe so. I need to believe that hope and overcoming are as universal as hardship. We have seen how a single event can completely rewrite the way we see the past, and the future. Despite such an event, some good things persist, and some new good things can even grow. While a lot of my poems imply a world of flux and uncertainty, where little can be taken for granted, I hope they can also provide a sense of solace, of possibility. The exceeding of limits and thresholds. The possibility of change and doing some good. The strength of being together and moving with others. The relief from pain.

In an idealised model of the world, there is an answer to every question. There is a reason for every event. Things can always be explained, if not anticipated. Everything is as it seems. But this is not the world I know. I think many of us experience a world far in excess of this idealisation. Flux and stability, pain and comfort, despair and hope, uncertainty and understanding – they walk together. The book is in a constant dialectic between entrapment and escape.

Paula: Indeed. The event in Christchurch tilted us at such a human level. I am a great believer in hinges as opposed to confrontation, connections rather than disconnections. For me that is what marks the pleasure of my reading experiences, such as your book. What poetry books have offered you solace or connection or breathtaking possibilities over the past year or so, but at any point in your life?

Gregory: I agree. The world can be seen in terms of its disconnections, animosities – its radical otherness. But I see that as the enabling space for bridges, for empathy and understanding. This is the condition for knowledge and for being together with others, for the grasping mindsoul looking for an island to rest on, awash in a dizzying ocean.

As for poetry books, there are so many! Since we’ve been talking about my book, I’ll use that as my constraint. Reading and writing are almost indistinguishable for me (you gotta eat to live), and these books were absolute pillars when I was writing Under Glass…

Tusiata Avia’s Fale Aitu | Spirit House. Soul-slaying. I often lament the lack of action and politics in New Zealand poetry. I sense a general sentiment that politics in poetry is “too prescriptive” or “ham-fisted” but I think that’s a cop-out. Those are not reasons to remain silent. My opinion is that our poetry community needs to speak up more, to do more work, to not be lost in the complacency of this privileged bubble of liberal high (and white) culture. Race, class, gender – they’re all here, beautifully woven into Tusiata Avia’s work. She’s not fucking around.

Anne Carson’s Nox. A sparse and fragmented work. Grief and memory. Love. Such a beautiful object, too. What she makes of the scant traces of her brother.

Raul Zurita’s Dreams for Kurosawa. Otherworldly. Heartbreaking. A very strange combination of elements: traces of trauma under the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, homage to Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, and ghosts everywhere.

Mary Burger’s Sonny. This book has been very influential to me – even since my first book, This Paper Boat – in form, in diction, in tone, in subject matter. I think it was Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle who recommended it to me. It showed me the power of plain prose and diction, and the power of arrangement and organisation. Like me, Burger is invested in interrogating and pushing the limits of the writing of selves. Like me, she is also invested in interrogating the conditions and limits of knowledge. The writing about her past collides with that of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American physicist who was credited for being the “father” of the atomic bomb.

Paula: This is a terrific list. Thank you. I have been thinking about the fingertip traces your book has left on on me – that sometimes act as tiny questions and that sometimes resemble little melodies. Did writing this book raise a question for you – large or small? In the process of writing or upon completion?

Gregory: All kinds of questions. A lot of self-centred ones, especially if I’m in an anxious mood. Will people accept this book as poetry? Is it even any good? Did I do my best? What constitutes success for this book, and for myself? What does my poetry mean to me? These are questions that have no real answers, and I’ll be taking them to my therapist, ha.

And some bigger, more difficult questions, after the book’s release and after Christchurch. What are the possible functions of poetry in our contemporary world? At one of its lowest points, poetry, for me, is so often an institutional and institutionalised form of nostalgia and conservatism. Why is it so enamoured with its own past? I don’t know if I’ve encountered another medium that is as hell-bent on dogmatically validating itself based on historical precedents and norms. At another low point, poetry is a site of postmodern whimsy, irony and impotence. If I were being charitable, I can understand that perhaps this is driven by the belief that almost everything can be and is subsumed under the totality of capitalism, and that resistance involves finding the most non-utilitarian, non-functional gesture possible. At other times, I think that this is simply a sneering cynicism. And I find that to be incredibly lazy and dispiriting. When our world is confronted by planetary annihilation and the increasing visibility of fascism and white supremacism, these attitudes are unacceptable to me. So what does it mean for poetry to adapt, and move forward?

What should the New Zealand poetry community be asking itself? I am afraid of particular kinds of silence. The silence of grief and shock, and the impossibility of witness and testimony, is of course understandable. But why do I also have the sense that there is also the silence of privileged complacency and passivity? The roots of colonialism – and the conditions of white supremacism – run deep, and I believe it’s our responsibility to start digging in our own backyards. It is a necessary labour for all of us.

Paula: I utterly agree. A necessary labour for all of us.

What do you like to do as a counterbalance to poetry?

Gregory: I work as a programmer and that offers me a world with a lot more certainty. There is still a lot of creativity and imagination involved in programming, especially in how you approach a problem. There is a caricature of programming that implies there is always a correct way to do things but that isn’t accurate. There are many possible solutions to any one problem. However, in the context of my work, the ends of programming are often certain – the problem itself is usually fairly determinate. What you are trying to get out of the program is usually fairly determinate. With poetry, utility and ends are always in question, and I may never know ultimately what “purpose” or function a poem serves. So having this kind of existential stability in my working world as a programmer can be a real comfort, as a point of difference. At the same time, there is such a thing as speculative programming, but I don’t yet have the intent, vision or skill to get there. In saying all of that, sometimes programming and poetry can feel very similar to me, both language-driven, both world-building. From that perspective my escapes become more recreational and indulgent ones. I love hanging out with my partner and watching Netflix. I love playing video games. I love watching trashy horror movies. Also activities that involve my body to a greater degree than the mind – swimming, cooking, listening to music, playing with the cat, eating, sleeping!

Auckland University Press page