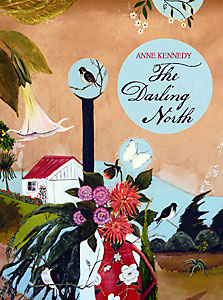

Anne Kennedy has many strings to her writing bow. She writes fiction, poetry and screenplays, and has gathered wide readership with her ability to draw upon a keen intellect, empathy, humour and a musical ear. This year she won the Poetry Category of The New Zealand Post Book Awards, with her collection The Darling North (Auckland University Press, 2012); a decision that delighted her poetry fans (Sarah Jane Barnett, who was also shortlisted, sung the praises of Anne’s poetry in a Listener interview). Anne’s debut collection, Sing-song (AUP, 2003) won The Montana New Zealand Book Awards and her follow-up, The Time of the Giants (AUP, 2005), was short-listed. Very few New Zealand poets have received such sustained honours (perhaps Cilla McQueen?). This year also saw the release of her critically acclaimed novel, The Last Days of the National Costume. Anne has spent a number of years teaching fiction and screenwriting at the University of Hawai’i, as well as teaching part-time at Manukau Institute of Technology.

Anne’s poetry is a joy to read. While you might find traces of similarity, her poetry is unlike that of any other New Zealand poet. Narrative energy is at the heart of her poems, poems that range from long to longer to book length. Her poems emerge from a life of reading and the reading of life. In ‘The Darling North’ poem there is a strong debt to Frederick E Manning’s Old New Zealand along with North by Seamus Heaney (she acknowledges these debts in her endnote), but the poem reaches deep into other experiences. There is a vivacity of detail, words that tremble and surprise on the line, a movement that is as much onwards as it is hesitation. Onwards, because you are in the sway and swerve of narrative motion, hesitation because the elasticity and surprise of words stalls you. Each line is a musical haven, where a note is struck and then counterbalanced or echoed or augmented:

I put my coat on over my nightdress and navigate

the trembling upper veranda, its nervous

kauri planks penned like wild horses under my feet

and I bounce down the foaming moonlit steps

to the garden, where a cat scallops, and hedgehog

snuffles obliquely into flax. It is cool.

Anne kindly agreed to an interview for Poetry Shelf:

Did your childhood shape you as a poet? What did you like to read? Did you write as a child? What else did you like to do?

To me, writing is partly about searching, and that’s what I was brought up to do. There were always books, and they were treasured (from Paradise Lost to A Town Like Alice), but I don’t know how anyone got time to read them because the house was busy with people, debate, drama. Looking back, we contended with philosophical gulfs on a daily basis: My parents came from different social classes, the Sixties happened, and in those days the Catholic schools peddled a sense of difference from mainstream society. (I don’t know if this was good or bad, but the artist needs to stand apart some of the time, if we are to believe Bourdieu). Overall, everything was up for question, and so the thing was to keep on searching.

One day, not long after I started school I, realized with a rush that if you could write, you could write a book. I threw a sickie (easy in our house), and wrote a tiny poem book (in Anne Carson’s ‘off hours’) in which every page ended in the sound ‘ee’. I was very proud of it and after that never stopped writing.

I don’t think we can underestimate how important literacy is, ‘in the first place’ (to quote Janet Frame), for creative writing. A while back, people were chuckling over John Key handing out Prime Minister’s awards for ‘literacy’ to three of our most eminent writers. No doubt he meant literature, but there’s some truth in the mistake. It all begins with being given the power to read and write well, yet more and more children miss out. I’m lucky that being taught early on meant the page represented freedom, only freedom. I’ve taught students who are intensely creative and great wordsmiths but struggle to translate that into writing because they’ve been failed by the education system.

Poetry on the page begins when you are five.

I was never without a novel (Rosemary Sutcliffe, C. S Lewis, Dodie Smith) , but when I was about seven I was given Peacock Pie, a collection of little story poems for children by Walter de la Mare, which I loved, and worse, copied. Later I was given an anthology for kids called This or That or Nothing, which was more confronting, with poems about nuclear bombs and suicide. It had an assortment of wonky fonts and a bright orange cover – very 1968. Poetry suddenly seemed subversive and shocking. I lived in that book for a year – and also copied it shamelessly. This is how people learn, I just didn’t know it then. (This is why your work with children’s poetry is so important, Paula.)

There was also the Bible, listened to at Mass. (‘Consider the lilies of the field, they toil not neither do they spin.’) I don’t remember anyone ever cracking open the text themself: it was always aural, and the rhythms and the far-fetched stories are still with me. That might seem contradictory to my point about literacy, but literature is the spoken written down.

You had developed a substantial reputation as a fiction writer (innovative, musical, poetic, complex, with strong relations with the real world, imagined worlds, and literary worlds), before you published poetry. What drew you to this different form?

I always wrote poetry. My first two fiction books are partly in poem form, but yes, I did leap over a kind of doorstep. My fiction seemed to be being read by a poetry audience which is strangely more accepting. Also I felt like my fiction was a failure, and I needed to stop!

I agree that your fiction is sumptuous and poetic (no way a failure!) and generates a reading experience that is quite breathtaking. Your poems are narrative driven — as a reader I get caught up in the arc and sidetracks of the narrative impulse, but there is so much more going on (as with your fiction). On so many occasions, musicality is the poem’s lifeblood, along with luminous and often surprising detail, light-footed and shifting syntax, and snatches of story that draw people and places close. What are key things for you when you write a poem?

One of the key things is a kind of key, or a tonal centre. As a reader, I find myself looking for a departure from a central idea or theme and a return to it – there’s a glorious tension in that. I’m drawn to modern and contemporary narrative poets like Anne Carson, Albert Wendt, W. S. Merwin, Williams Carlos Williams, T.S. Elliot, and also and especially Virgil, who daringly stray a long way from ‘home’, but inevitably return. When Vela travels away from his time, his people, his seriousness, even his story, coming back is all the better.

While I can admire a short poem that is a thing in itself but not a story, I couldn’t write one to save myself. There would be so much pressure on it! A poem only lives for me if it is part of a network, a litany.

On a line level, I love the element of surprise, but also plainness, because surprise is only interesting when it is set like a gem. Ian Wedde is very good at this.

Yes! I think it is the plainness that elbows room in the surprise and the surprise that makes little leaps in the plainness. You continue to write poetry, you continue to write fiction. Is this a supportive relationship? What is different about doing one rather than the other?

I wish I knew, and I’d stick to one or the other, probably fiction! Sometimes I try to work out the differences between the genres but can never get very far.

What poets have mattered to you over the past decades? Some may have mattered as a reader and others may have been crucial in your development as a writer.

My brother, Philip, was the first adult poet I read. Most of what we still have of his was written in his teens. He died at 22. I’m working on a sequence grouped around one of his poems, which I find a very moving experience. It’s taking me a long time. (I hope I haven’t jinxed it by talking about it.)

There were poetry books in the house because of Philip: Hone Tuwhare, James K Baxter, Sam Hunt, who were so important for their New Zealand vernacular – and because they are incredibly good. But they’re all men, and as I got older I sought out women poets – Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, Maya Angelou, and imagist poets like H. D.

When I first read Gertrude Stein, it was like a wall crashing down. But another went up, a Steinish wall: I think I embarked on a years-long phase of not caring about the reader. I put it down to not caring enough about people. Emotional maturity is important in a writer.

All these poets I read as a reader and as a writer. I don’t separate the two.

Perhaps this emotional maturing strengths the presence of heart in the risks you take as a writer. What New Zealand poets are you drawn to now?

Some young poets I’ve noticed recently make you swell with the knowledge that this business is in good hands: Sarah Jane Barnett, Amy Brown, Ya-Wen Ho, Courtney Sina Meredith, Steven Toussaint, Ashleigh Young. And Ellie Catton’s The Luminaries is intensely poetic. I read it in the same way as I do a poem.

I agree with you on The Luminaries. A number of reviews have used the word ‘luminous.’ Poetically luminous, at the level of the sentence for a start. Do you think your poetry writing has changed since Sing-song was published in 2003?

I hope so. I hope I’ve got better, but you can never really know. As Flannery O’Connor says, ‘Mystery isn’t something that is gradually evaporating. It grows along with knowledge.’

You have spent the past decade living between New Zealand and Hawaii. Is a sense of home an important factor as you write? I wonder if your writing is a way of laying down roots, both familial and literary. Or do you feel torn between places and thus restless as a writer?

I laid down roots through writing a long time ago, and moved on from that. I think that’s quite a common pattern. But moving between countries, having two realities, has undoubtedly played into the collision of worlds that the imagination continues to be.

Do you think the poetry writing landscape in New Zealand is vastly different than that in Hawaii? Is ethnicity or race an issue?

Ah, this is all so complicated! Ethnicity is a hot issue in Hawai`i. People talk about it constantly, and are defined by it (‘that Chinese girl’ kind of thing), which is at once refreshing and difficult. And of course poetry lives in that world. One of the big recent movements is Pidgin poetry, which has such a gorgeous sound because it is essentially a spoken language. Two of my favourite Local poets who write in Pidgin are Lois Ann Yamanaka (who also writes novels), and Ann Inoshita: ‘Going come dark so my madda call me / fo go back inside da house’ (‘TV’). Indigenous Pacific poetry with a political drive is also strong in Hawai`i, with poets like Brandy McDougall, Craig Santos Perez, and Robert Sullivan, being part of the Pacific-wide picture. (See my piece on Hawai`i poetry in Ka Mate Ka Ora: http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/kmko/03/ka_mate03_kennedy.pdf)

On returning to Aotearoa, I remembered that ethnicity is like sex, you can’t talk about it publicly. And yet, this is a very racist country. Maori and Polynesian poetry, and in fact all non-white poetry, is largely ghettoized. I’ve been shocked to be involved in event after event that is entirely white. I’d forgotten that could even happen. So while it is considered tasteless to mention ethnicity, people happily exclude based on it.

I put this racism down to a reluctance to entertain different aesthetics. The kind of poetry I like is ABOUT being open to difference, to different codes, to different musics.

Pakeha writers have got to hope that when they are in the minority, which will happen eventually, the people in the majority remain open to the aesthetics of other.

What irks you in poetry?

The ‘isn’t-my-life-lovely’ poem.

What delights you?

Curious narrative. Hidden form. Tossed-offness. Humour. And the thing I didn’t know would delight me until I read it.

Name three NZ poetry books that you have loved.

It’s probably too nepotistic of me to mention Voice Carried My Family, by Robert Sullivan, so: Wild Dogs Under My Skirt, by Tusiata Avia; Thicket, by Anna Jackson; The Lifeguard, by Ian Wedde.

Name three overseas poetry books that you have loved.

I’ll limit myself to North America for now: Glass, Irony, and God, by Anne Carson; Povel, by Geraldine Kim; Rebellion is the Circle of a Lover’s Hands, by Martín Espada.

The constant mantra to be a better writer is to write, write, write and read read read. You also need to live! What activities enrich your writing life?

Being with family trumps everything.

But lots of other things. If you feed only off creative writing and its world, you might end up with the literary equivalent of mad cow disease.

Some poets argue that there are no rules in poetry and all rules are to be broken. Do you agree? Do you have cardinal rules?

Form is a kind of gravity. If there wasn’t any, everything would fly away. I enjoy formal constraints and the freedom to muck them up. For instance, in The Family Songbook John Newton’s handling of meter is spectacular, and yet the lines on the surface seem roughed up in best possible sense. That kind of controlled spokenness I can only dream of writing.

In the end, the elements of a poem are there for the greater good. I like Eavan Boland’s quite essentialist take on what images do in a poem: ‘Images are not ornaments; they are truths.’

Do you find social media an entertaining and useful tool or white noise?

How could we live without it now? It brings people together in new configurations. Also, the written word is lifeblood again. It was languishing for a while there.

You have dedicated significant time to teaching creative writing at The University of Hawaii and, in a more part time role, at Manukau Institute of Technology. What do you see as important in your role as mentor?

I think I’m there to open some conceptual doors. It took me a while to work out process. Teaching is like constructing a narrative – in what order should you introduce ideas so they make sense? I’ve spent a lot of time trying to get this right, usually using close readings of texts. It’s exhilarating to have a class share a text, to get it, enjoy it, learn from it. (I got some of that just from reading and talking to people, but you don’t get a degree from hanging out with friends!)

I was surprised to find that I like teaching students who will probably not end up as writers, it’s just something that will enrich their lives. But of course it is also incredibly exciting to work with someone who is dripping with talent.

Women writers have often managed a writing life along with domestic demands and have been denigrated for writing that embraces domestic concerns. Any thoughts on this? Is there still a case for feminist appraisals of writing and the institutions that both reproduce and critique it?

Poetry isn’t sealed off from daily life, so until women have equal pay, equal opportunity, and don’t have to live in fear, feminist principles must have a place in writing and criticism. Although women poets are published in greater numbers now in Aotearoa (it could hardly be fewer than when it was just Jan Kemp!), there’s still chauvinism, still old farts and not so old farts who view women’s domestic-themed poetry as ‘soft’.

The big names of poetry are still mostly men, and the theorists we revert to are men even though there’ve been generations of feminist theorists now.

When I was young, feminist poets and theorists were vital to my vision of myself as a writer. To my list above I could add Denise Levertov, Anna Akhmatova, Anne Waldman, and Hélène Cixous, Elaine Showalter, and Simone de Beauvoir. I don’t think I would be in print without them. I’m worried we may have stopped making consciously feminist poetry too soon. But Pasifika women seem to not have forgotten the struggle. Tusiata Avia, Selina Tusitala Marsh, Courtney Sina Meredith are inspiring a new generation of young women.

Finally if you were to be trapped (in a waiting room, on a mountain, inside on a rainy day) for hours what poetry book would you read?

As long as I can be trapped from November on, Bernadette Hall’s forthcoming book, Life & Customs.

Thank you, Paula.

Thank’s Anne. Bernadette’s book is due in November and is published by Victoria University Press. I will review it on Poetry Shelf.

Links:

Auckland University Press page

New Zealand Book Council page

Scottish Poetry Library introduction to Anne Kennedy

Anne Kennedy on the New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre

Anne Kennedy’s author page at Allen and Unwin

Anne Kennedy on the New Zealand Electronic Text Centre

Anne Kennedy in Best New Zealand Poems 2005

Anne Kennedy’s bibliography in the Auckland University Library’s New Zealand Literature File

NZ on Screen page

Interview for Unity Books

Review of The Darling North in Metro

Review of The Darling North in Landfall

Review of The Darling North in NZ Books

Review of The Darling North in The Listener