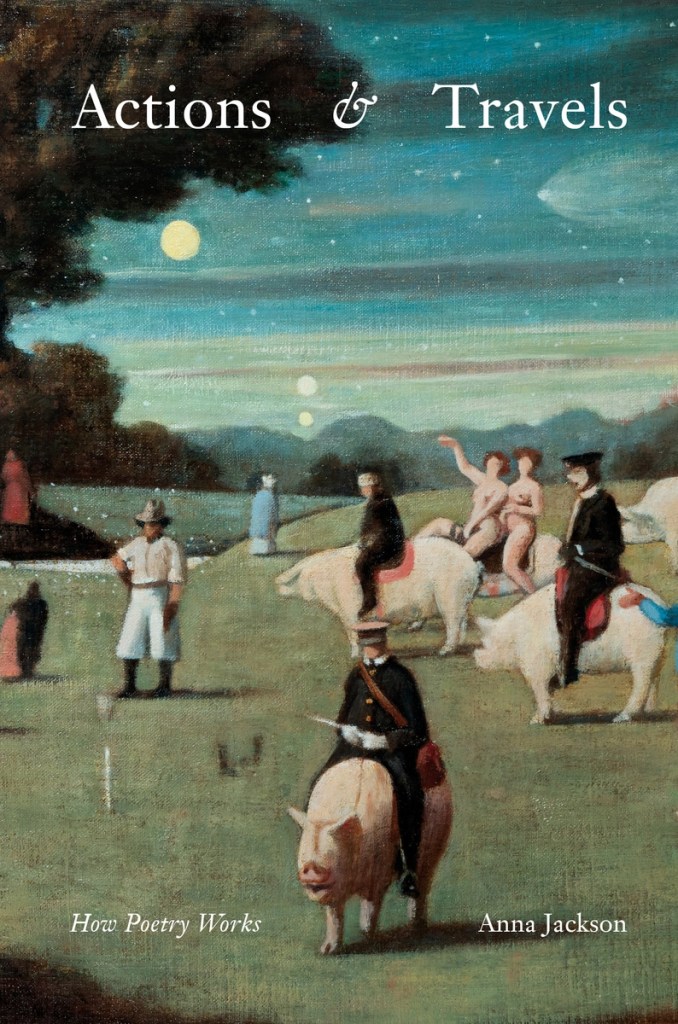

In 2022 I aim to have email conversations with poets whose work has inspired me over time. First up, Anna Jackson. Very apt, as Anna’s new book, Actions & Travels: How Poetry Works, is published by Auckland University Press today.

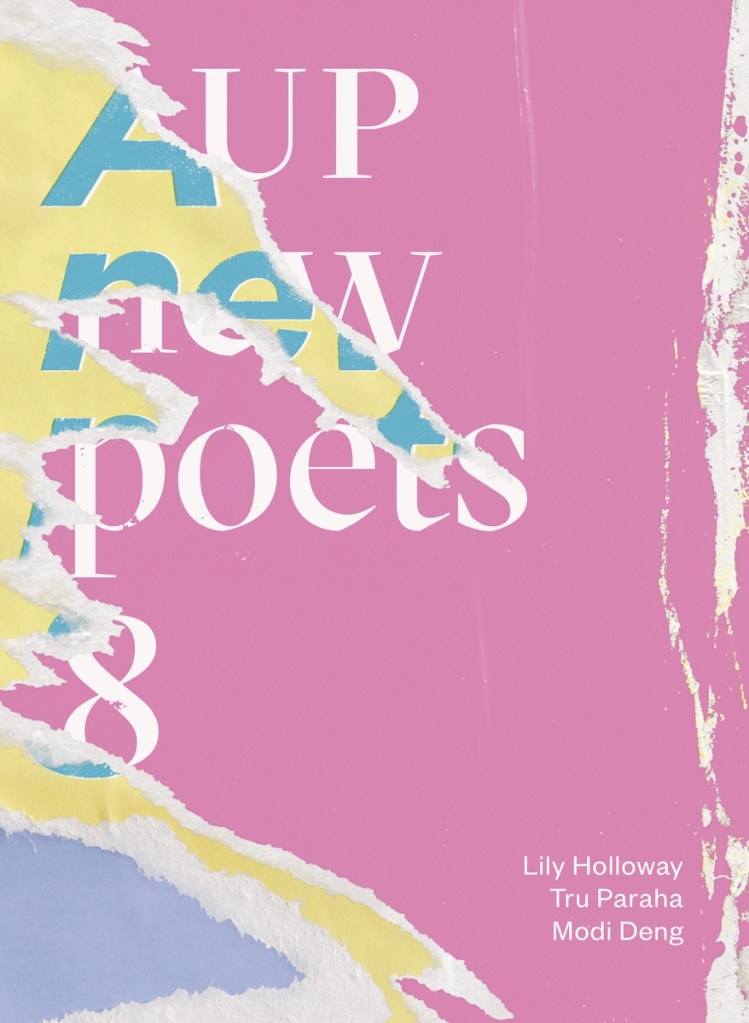

Right from the start Anna’s poetry has touched a chord with me. In the early poems, the litheness on the line, the measured wit, the roving curiosity captivate, as in AUP New Poets 1 and The Long Road to Teatime (2000). In The Gas Leak (2006) Anna steps into narrative, but family remains in acute focus. There is a humaneness at work, little wisdoms, a playful yet serious pushing at familial boundaries. When Pasture and Flock: New & selected poems arrived in 2018, I admired the new growth, myriad viewpoints, shelter and flight. We discussed poetry and the Selected Poems in a Poetry Shelf interview.

Paula: Not long after my debut poetry collection Cookhouse appeared (1997) you popped a note in my pigeon hole at the University of Auckland inviting me to afternoon tea. We meet up for the first time and have been sharing afternoon tea ever since, exchanging thoughts on poetry, what we read and write, the world at large and the world close at hand.

To celebrate the arrival of your book Actions & Travels: How Poetry Works, I thought a slowly unfolding email conversation as I read the book would be perfect.

I love the title because it underlines the way poetry is full of movement. I also like the open-spirited ‘how poetry works’. I started listing verbs under the umbrella word, ‘works’: sings, captivates, challenges, narrates, mystifies, dreams, soothes, astonishes, functions. Was it hard settling upon a title?

Anna: I still love Cookhouse, I used to carry around my copy of it so I could read an afternoon tea poem wherever I was in the day. Yes, movement is exactly what I love in poetry, movement and pace. The title comes from a quote I love by Anne Carson, from an interview with her, in which she calls a poem ‘an action of the mind captured on the page’, an action that the reader has to enter into, and move through – so that reading poetry is a form of travelling. Actions and Travels was my working title for the book from the start, but I did try to come up with something that would be a bit less obscure. Instead, the subtitle has had to make it clear that this is a book about poetry. ‘Works’ is a very functional sort of word, less poetic than sings, or mystifies. But when I’m writing poetry myself that is what I am looking for, whether the poem is working or not.

After I’d finished the book, and was editing the final chapter for the last time, a chapter about the poet’s invisibility, and a poem’s flights, I thought Flight and Invisibility could have made a good title for the book. But I like the more prosaic quality of Actions and Travels too.

Paula: Before I move onto the book, is there a poetry book (or two) you have carried with you in the past few months or so?

Anna: Oh, there is, actually – Anne Kennedy’s The Sea Walks into a Wall (AUP). It is a collection that fits different spaces of time, with some shorter poems and some longer poems, so I am quite often picking it up again, and the longer poems in particular I return to at different times. They repay rereading and the collection as a whole also gains in substance and resonance with rereading. It has been a good summer book, and a good counterweight to the Knausgaard novels that have been my other summer obsession.

Paula: I am fascinated how a poetry collection reaches us in different ways over a period of time. In the introduction to Actions and Travels, you discuss John Keats’ brilliant short poem and the hand reaching out: ‘I hold it towards you’. This is poetry. I always think of the bridge I cross as I enter a book. So many ways of crossing, sometimes impossible, so many different bridges. I am thinking of the Bridge of Wonder. The Bridge of Knots. The Bridge of Song. Heaven forbid The Bridge of Dead Ends. What matters to you as you enter a poetry book?

Anna: Different things matter according to the book – I suppose it depends on what mattered to the poet. Wonder, knots and song – those are all things that might draw me in. I was talking to artist/curator Nathan Pohio about the importance of grit in writing and thinking – it was what he was working to include in his own writing – and I thought this was such a good word, something that slows you down and maybe even hurts a little bit, something that makes you need to bring something of yourself to the experience. Grit rather than a dead end – something that invites collaboration and involvement rather than shutting you out. But not something too smooth, either – not something you are forgetting as you read it.

Paula: Collaboration seems important. Openings for the reader rather than closures. When you first came up with the idea for Actions and Travels, what sort of things did you hope it would do. From my early stage of reading, I am finding it a source of openings and inspiration. It prompts me to action as a writer and travels as a reader, and vice versa.

Anna: I hoped it would allow readers to take some time over some poems I love, some of which they might already know, some of which may be new discoveries for them. A lot of people I talk to don’t read poetry but read novels or non-fiction, books they can be immersed in. Part of what I love about poetry is what a quick reading hit it can give you, how you can come across it on social media, in magazines or on posters and be instantly transported. And poetry is reaching more and more readers this way. But Actions and Travels offers a slower reading experience for readers who want to follow my own responses to the poems I read. I hope readers will also want to stop and think about their own responses to the poem and be interested in any differences there might be between their own initial responses and my own. I hope slowing down the reading, and returning to some poems that might already be familiar, will also make space for the poems to resonate deeply, and maybe continue to haunt the reader after the book is finished.

Paula: I was thinking similar things when I wrote Wild Honey. I love the way poetry can fit in small moments, in a pocket, a bag, or while you drink morning coffee. Long poems are immensely pleasurable, but short poems equally so. Bill Manhire sent me a poem he recently had published in PNReview, and I haven’t stopped thinking about it. It’s musical, enigmatic, physical, a haunting Covid snapshot. Tell me a short poem you have read recently that has lingered in your mind.

Anna: Yes, I loved the way Wild Honey gave us time with each of the poems you discussed, and with the poets too – I loved the way it brought the poets into the picture with biographical details. Actions and Travels doesn’t have the same scope but I hope it does open space up in a way that is a little bit similar. As for a short poem, for brilliance with brevity my favourite poet would have to be Lydia Davis, and the short poem of hers I think of most often is ‘Improving my German’, which goes like this:

All my life I have been trying to improve my German.

At last my German is better

—but now I am old and ill and don’t have long to live.

Soon I will be dead,

with better German.

And the poem I’ve been talking most about lately is Erin Scudder’s Jewel Box. It is definitely the best poem about grit I can think of. It can be found in Sweet Mammalian Issue 8.

Paula: I love ‘Jewel Box’. It has got me thinking of poems in this way. Yes as jewel boxes, but also the grit that rubs against you. There’s the ‘peach meat’ and there’s the grit. Glorious. As I said long poems are equally rewarding. I wrote long poems when I was doing my Doctorate and my daughters were young, as I felt I could fit something big in small moments. Your long-poem chapter is entitled ‘Sprawl’ and that is so fitting. I am thinking of the way your ‘I, Clodia’ sequence (can I call this a long poem?) both sprawls and concentrates on small poems. Clodia’s voice is the connective tissue. And I am also thinking of The Gas Leak. I see grit and peach meat in both these projects. What draws you to the long poem? Do you like writing them?

Anna: I think of ‘I, Clodia’ and ‘The Gas Leak’ in terms of sequence rather than sprawl, because of the concentration, as you say, in each of the small poems. Every poem of those sequences I think of as quite tightly wound. I did love having the space that the sequence gave to build narrative and to develop ideas over its course. That is what sprawl offers too but I think of the sprawling poem as having more looseness and more fluidity to it, so it can be very relaxed, open and looping. I don’t think I’ve ever really written a sprawling poem though I would like to try. I love your ‘Letter to Anne Kennedy’ which I include as an example of sprawl for the way it unfolds so loosely and easily across the pages. There are patterns too, an intricate architecture of departures and returns, repetitions and echoes, and shifts in perspective, but they are very unobtrusive.

Paula: ‘Tightly wound’ is apt – and it also resonates with wound/ injured. ‘Resonates’ is a word you explore in ‘Simplicity & resonance’. If the stars align in a poem for a reader, it resonates – as in the examples you navigate. I find I am reading the book at a snail’s pace because of the interior resonances. The way I stall on a poem, and then want to read more of Emily Brontë, Robert Frost, Bill Manhire, Rebecca Gayle Howell, Eileen Duggan, William Butler Yeats (or return to). Yet I am also compelled to keep reading – as I might with a detective novel -regardless of what else needs to be done. Did you find this book a challenge to write? It seems to be a book written out of deep love for the subject matter and that shows.

Anna: Resonance is interesting to think about because as you say it depends on the relation between the reader and the poem – what resonates for one reader may not be what resonates for another – but also on how the poem sets up the possibilities for resonance. So it is both internal to the poem and external to it – the way the thought of a wound or injury is suggested by the word wound as in wound up, but is not actually present in the phrase tightly wound. I wondered at the time, actually, about writing “wound up” instead of tightly wound, because I didn’t particularly want the association with injury to come into play, but then I thought, tightly wound is better – it is how you might describe a person, a mood, whereas wound up suggests clockwork, something more mechanical, and something wound up in order to then do something else. And I thought, after all, there is also some kind of injury or wound at the heart of each of those narratives.

Language is complicated! And part of the beauty of poetry is how the poet works with all those complications and manages the interplay of associations. That is what I loved most about writing the book, the close attention it made me pay to all these sorts of details in the poems I was reading. So yes, the writing was totally driven by my love of the poetry.

Paula: It shows. Your sentences are exquisitely crafted. There is a fluency about the book that invites the reader in. I like the way the footnotes are not evident until you see the notes at the back. This is a book of ideas but it resists academic jargon and theory speak. What were your thoughts on how you would write it?

Anna: I loved it when you said, earlier, that you were reading it like a detective novel! It doesn’t have a lot of plot or suspense but I did want readers to be able to follow my thinking and my reading. So yes, instead of footnotes there are notes at the back you only need to refer to if you want to know where a quote comes from. For the same reason, I cut back on references to other critics, so that each chapter would just be shaped by my own thinking and observations. There are times when another critic’s reading really helps me make a point of my own. I give Edward Hirsh’s account of his childhood reading of the Emily Bronte poem because it is such a good example of how resonance can come both from inside and outside the poem – the experience he brought to it, the idea that his grandfather was talking to him through the poem, was his own experience, but the ways the poem allowed that sense of being haunted and the ways it conveyed the exact sense of loss he felt are very specific to the poem, with its stormy scenery, insistent rhythms and echoing rhymes. So some critics are referenced but it is mostly just my own voice, talking my way through the poetry, as the discussion of one poem leads to the introduction of the next, to develop an idea about the political work a poem can do, for instance, or what is going on when poets translate or rework poetry from the past.

Paula: I love the way you weave in the voices of other critics. To me these appearances service connection and building rather than dismantling and disconnection. If as poets we write on the shoulders of the poems and ideas that have preceded us, we also write within the ‘fire’ of the present and the urgency of the future (as you explore). We reach out to the established poets and we listen intently to the new and younger voices. I found I had to leave things out of Wild Honey and it kept me awake at night (chapters, poets, poems). Did you have similar struggles and pain?

Anna: Yes, I did, although Actions and Travels is a very different book. Wild Honey is so inclusive and so wide-ranging and comprehensive an account of women’s writing in New Zealand, you can include so many more poets than I had the space for, and write about their work in so much depth and detail, but even though the book is so inclusive I know how much you agonised over the limits even to so large a book. In some ways it is harder, when a book is so inclusive, to leave any particular poet out. Actions and Travels is so much smaller and it covers poetry from the US and UK as well as New Zealand, and goes back to the sixteenth century and even earlier, much earlier in the case of Sappho. So there was no way I could include every poet who is important to me, or even all my most absolute favourite poems. There are absolute touchstone poets I left out, like Stevie Smith, Anne Kennedy, Lydia Davis, Seamus Heaney, Robert Sullivan, to name just a few, and poems I often return to that are not in the book at all, or are mentioned briefly in passing, like Gerard Manly Hopkins’ ‘Oh, the mind, the mind has mountains’.

I did begin with an idea of some of the poems I wanted to include, but I allowed the readings in each chapter to suggest connections between poems, and I wanted observations to be able to develop into arguments or extended thoughts on how poetry can sustain the particular qualities I was finding in it, so often the poems are chosen for how well they illustrate an idea I am exploring, or how well they fit in the chapter between two other poems. It isn’t a canon-building or a curatorial exercise, just a free-flowing discussion of poetry and ideas. Having said that, I do love every one of the poems that I have included, and I do think they make a beautiful collection together in the book.

Paula: I love the addition of writing prompts linked to each chapter at the back. I really like: ‘Find the words that resonate with you – at a paint shop? In a fabric shop? In a knitting pattern? Put one or more of these words in the centre of a short poem.’ Have you tried any of your prompts?

Anna: The poetry prompts are meant to be taken lightly, tried out to see if anything comes of them. They are a way of setting the writer on a different course of thought than they might have been on. If you write with a loose grip on the instructions and let the writing go wherever it wants to, it will probably arrive at some concern or obsession of your own or draw on something of your own life, but coming at it from a different angle may lift your own story into something both stranger and perhaps more universal. Some of the poetry prompts are based on how I wrote some of the poems I’ve written – describing a physical action in such detail it becomes metaphysical (‘Evelyn, after apple-picking’), adding the word ‘Dear’ to turn a poem into a letter (‘Dear Tombs’), adding rhyme to turn free verse into terza rima (‘Dear Tombs’ again, and ‘Eleanor at the beach’), adding in elements to the scenario in Sappho’s love triangle poem (‘Being a poet’), some of the others too. But I haven’t actually started with any of my own prompts, to generate a new poem. I really should try them out.

Paula: I am particularly drawn to the ‘Poetry in a house on fire’ section as it seems apt for the difficult times we share – what with pandemic, protest, looming war, poverty, despair. Locally, globally. You turn to the poetry of younger writers such as Ash Davida Jane and Tayi Tibble (and yes, more established writers), and it excites me. I take heart from these younger poetry voices. I find poetry is so important at the moment. I want Poetry Shelf to be a place of connection and celebration. The edgy grit along with the soothe. What gives you solace at the moment? How does poetry fit into this ‘house on fire’?

Anna: Yes I think poetry is particularly important in turbulent times, both as solace and as a kind of resistance. Poets are writing more politically now I think than when I began publishing poetry, maybe because social media is already bringing together the personal and the political, maybe because these are such turbulent, politically charged times, though I also love, too, the way poets like Tayi Tibble and Ash Davida Jane are so funny even when they are at their most political. The poems that I find most soothing when events in the world are most overwhelming are poems of quiet but implacable resistance or refusal, there’s a kind of humour but it is very astringent. There was a time I wanted to read Robert Lax’s 1966 poem ‘The port was longing’ over and over again, as a kind of meditation, not of acceptance but of refusal. At the moment, Ilya Kaminsky’s ‘We lived happily during the war’ has a terrible resonance. His reading of it is extraordinarily powerful. It certainly isn’t soothing, it is terribly disquieting, raising such a difficult question of how to live in times of crisis. Does happiness become immoral? Poetry insists not only on an ethical but on an emotional response to such a question. I don’t think we ever want to let go of feeling.

Anna Jackson is a New Zealand poet who grew up in Auckland and now lives in Island Bay, Wellington. She has a DPhil from Oxford and is an associate professor in English literature at Victoria University of Wellington.

Anna made her poetry debut in AUP New Poets 1 before publishing six collections with Auckland University Press. Her most recent book, Pasture and Flock: New and Selected Poems, gathers work from her previous collections as well as twenty-five new poems. The book includes poems from Catullus for Children and I, Clodia, the two collections that engage with the work of Catullus, as well as poems about badminton, billiards, salty hair, takahē, head lice, indexing, proof-reading, hens, truth and beauty.

As a scholar, Anna Jackson is the author of Diary Poetics: Form and Style in Writers’ Diaries 1915–1962 (Routledge, 2010) and, with Charles Ferrall, Juvenile Literature and British Society, 1850–1950: The Age of Adolescence (Routledge, 2009).

Auckland University Press page

Anna Jackson website