Michelle and Iva, winning emerging poets

This event, steered by Siobhan Harvey, has become an annual event in Auckland on National Poetry Day. Check out the winning poems by following the link. Both terrific!

The 2016 Divine Muses XIII : evening of poetry was this year MC’d by Linda Tyler, Director of the Centre for Art Studies at The University of Auckland. The University’s Gus Fisher Gallery with its beautiful stainglass dome provided the wonderful venue for the readings.

Linda Tyler welcomed and invited this year’s stellar line up of poets to read from a selection of their own poems. Vivienne Plumb, current writer in residence at the Michael King centre in Devonport, read first; followed by Riemke Ensing, Maris O’Rourke, Siobhan Harvey, Jenny Bornholdt, and Gregory O’Brien.

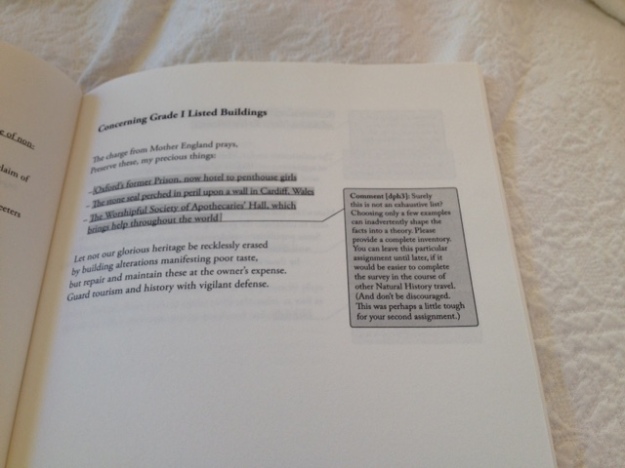

At the close of readings the winners of the 2016 NEW VOICES – Emerging Poets Competition were announced by judge Vana Manasiadi. Michelle Chote and Iva Vemic then read their winning poems. Unity Books of High Street kindly donated the book prizes for this year’s winners.

The last event of the evening was the launch of two new letterpress broadsheets. Limited Poetry Broadsheets were introduced last year by the organisers to help raise funds to support New Voices. The two new broadsheets were printed by Wellington letterpress printer Brendan O’Brien of Fernbank Studio. They featured poems by Gregory O’Brien and Jenny Bornholdt. Click here for further details

The winner is Michelle Chote and runner up is Iva Vemic.

New Voices, Emerging Poets Judge’s Report, 2016 (Vana Manasiadis)

I loved reading the entries for this year’s competition; it was an honour and a privilege to be entrusted with voices that took me to places as diverse as K road, Jerusalem, Santiago, Pike river, Prague and Kakamatua; and allow me presence during conversations with New Zealand poet elders, Denis Glover, Lauris Edmond; and American, Marge Piercy, Susan Howe. In all the poems I read, there was a magic and transport, and for me that is always the most important thing. I looked forward to reading the entries while I was still in Crete trying to find the threads myself, the connections in my case between words in different languages. And I thought about the words ‘language’ and ‘translation’ a lot – and certainly poetry contains a multiplicity of languages: of image, of sound, of turn, of contact. So when I finally got my hands on the entries, I looked for these different languages and their relationships to each other; and ultimately, to the translations. How was lonliness, love, loss being translated, sculpted and crafted and being offered to me, the reader, as something transformed? Water was a recurrring theme in this year’s entries, as was journey, and moving relationships with the dead and the living. So, fluidity, and arrival. I read the entries many times until I arrived myself at the shortlisted ten which succeeded particularly well in translating ideas of arrival, journey, surprise; and which showed deft use of the many languages of poetry. And I especially congratulate these poets tonight.

Highly Commended: I chose three highly commended poems this year, and the first of these is ‘Poppa’s Boat’, by Christel Jeffs, for the moving way themes of loss (of a beloved person, of childhood) and love, are evoked via turn and meticulous crafting. All five senses are alerted in this poem to memorable effect, the voice is authentic and assured, and it tells a story of presence, absence, presence in absence that is relateable, and felt true.

The second highly commended is ‘Home Thoughts, after Denis Glover’s poem’, by Annabel Wilson, a poem that insisted itself upon me. There’s a quiet confidence in the poem, a humility and ability to step back and let the images do the talking, that impressed me. The sustained image of the line drew me in and kept replenishing itself, and the implied dialogue with the poem’s inspiration, Glover’s ‘Home Thoughts’ pointed to the something bigger in poetry, to the community of voices.

The third highly commended is ‘Shoe Pads’, by Linda Lew, which was both delicate and dynamic in its treatment of the grandmother protagonist. The camera here pans wide and close in turns, as enormous historic events are checked by the grandmother’s quiet acts of love and shielding. I walked alongside her as she walked through decades of change, from Beijing to New Zealand. Always direct, never sentimental, she was kind and sturdy company.

Finalist: The second place goes to ‘A poem a day’, by Iva Vemich which, with its pace, choric repetitions, and surprising leaps of imagination made for memorable reading. I read this poem as a poem-essay, a poem that asks a question and shows its workings – in this case, ‘will poetry rescue’ (the poet, the community going about its daily business)? The responses – wry and perhaps a little ironic, but in a good way – were unexpected and evocative, and I was thrilled by many of the line breaks, and stream of consciousness connections.

Winner of the 2016 New Voices Competition: The winning entry tonight is ‘A colonised woman speaks’ by Michelle Chote. This was one of the first poems I read, and it absolutely refused to slip away quietly. It kept calling with its layers of polemicism and consonant crash. In this poem, expression is not the means to an ends, but the thing itself – the syllables and the hollows a body allows us. So tongue, air, taste and belly establish the organic imagery, embody fury and revolt in lines like ‘dash dipthongs at the drop of a beret’. Listen for the ending which is a perfect coming together of sense and sound. Having read the poem aloud several times in an effort to absorb the sound effects, I’m particularly excited to hear this powerful poem read tonight in this beautiful space, as the winner of this year’s competition.

Vana Manasiadis

![Performance photo Tusiata Avia[1]](https://nzpoetryshelf.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/performance-photo-tusiata-avia1.jpg?w=625&h=418)