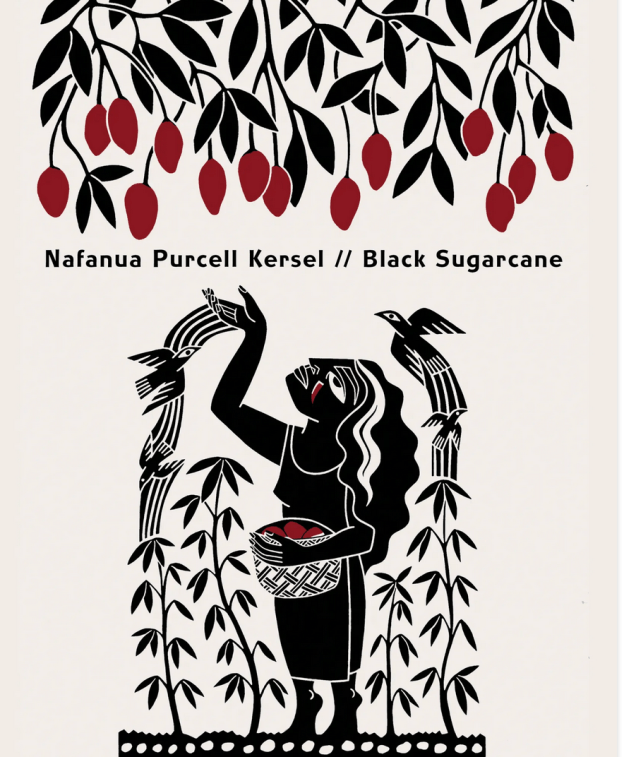

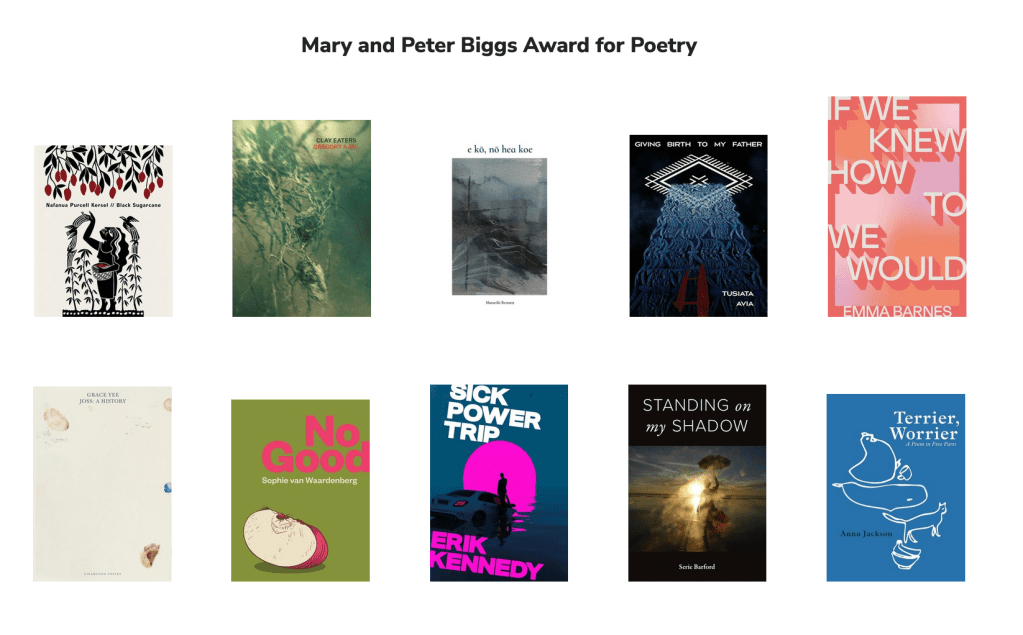

Black Sugarcane, Nafanua Purcell Kersel

Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2025

Moana Pōetics

We build a safe around our birth stones.

Craft it with a dream, a gourd, a drum-made

chant.

Pile it high with frigate bird bones,

song bones, bones of

cherished names.

We rub sinnet along our thighs and lash

our cache. Our stories kept sound, where words

and names and songs are not forgotten.

One day before, now, or beyond, something

with a heart drops a hank of its flesh

before us. It sounds like a drum and we know

it’s time

to undo the rope, iron-rock and bone-sand.

The stories, they tell us

that if we are the dark blue seas then we are

also the pillowed nights and days, soft with

clouds, spread half-open.

We are a tidal collection, hind-waters of the

forever we rally on, to break the staple

metaphors from the fringes.

Safe.

We sound together on a dance or

bark an intricate rhyme.

We, are the filaments of a devoted rope. We,

who contain a continuance and

call it poetry.

Nafanua Purcell Kersel

Nafanua Purcell Kersel’s debut poetry collection, Black Sugarcane is a book to savour slowly, with senses alert, ready to absorb the aroha, the myriad pathways, the songs, the prayers, the dance of living. The first line of the first poem, ‘Moana Pōetics’, is a precious talisman: ‘We build a safe around our birth stones.’ It is a found poem that uses terms from the glossary in Mauri Ola: Contemporary Polynesian Poems in English, edited by Albert Wendt, Reina Whaitiri and Robert Sullivan (Auckland University Press, 2010). The poem draws us deep into the power of stories, night and day, the ocean, safety, the power of rhythm. And that is exactly what the collection does.

The book is divided into five sections, each bearing a vowel as a title (ā, ē, ī, ō, ū), the macron drawing out the sound, as it does in so many languages like an extended breath. When I read of vowels in the poem, ‘To’ona’i’, the idea and presence of vowels lift a notch, and poetry itself becomes a ‘sweet refresh’, a warm aunty laugh: “Aunty Sia’s laugh is like a perfectly ripe pineapple / a sweet refresh of vowel sounds”.

Let me say this. There is no shortage of poetry books published in Aotearoa this year to love, to be enthralled and astonished by. We need this. We need these reading pathways. Sometimes I love a poetry book so much I transcend the everyday scene of reading (yes those bush tūī singing and the kererū fast-swooping) to a zone where I am beyond words. It is when reading is both nourishment and restoration, miracle and epiphany . . . and that is what I get with this book.

Begin with the physicality of a scene, a place, an island, a home. The scent of food being prepared and eaten will ignite your taste buds. Pies filled and savoured, luscious quince, the trickster fruit slowly simmered, a menu that is as much a set of meals as a pattern of life. Move into the warm embrace of whanau, the cousins, aunties, uncles, parents, grandparents, offspring. And especially, most especially, the grandmother and her lessons: ‘”If you want to learn by heart, / be still and watch my hands” (from ‘Grandma lessons (kitchen)’).

Find yourself in the rub of politics: the way you are never just a place name and that where you come from is a rich catalogue of markers, not a single word. The question itself so often misguided and racist. Enter the ripple effect of the dawn raids, or the Christchurch terrorist attack, or poverty, or climate change, crippling hierarchies. And find yourself in the expanding space of the personal; where things are sometimes explored and confessed, and sometimes hinted at. I am thinking pain. I am thinking therapist.

Find yourself in shifting poetic forms, akin to the shifting rhythms of life and living: a pantoum, a found poem, an erasure poem, long lines short lines, drifting lines. Find yourself in the company of other poets, direct and indirect lines to the nourishment Nafanua experiences as a writer: for example, Lyn Hejinian, Kaveh Akbar, Karlo Mila, Tusiata Avia, Selina Tusitala Marsh, Serie Barford, Konai Helu Thaman, Dan Taulapapa McMullin. So often I am reminded we don’t write within vacuums. We write towards, from and because of poetry that feeds us.

Bob Marley makes an appearance so I put his album, Exodus, on repeat as I write this. It makes me feel the poetry even more deeply. This coming together, this ‘One Love,’ this getting together and feeling alright, as we are still fighting, still uniting to make things better in a thousand and one ways.

I give thanks for this book.

Listen to Nafanua read here.

‘

Nafanua Purcell Kersel (Satupa‘itea, Faleālupo, Aleipata, Tuaefu) is a writer, poet and performer who was born in Sāmoa and raised in Te-Whanganui-a-Tara, Aotearoa. Her poetry has been widely published. She has an MA from the IIML at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington and won the 2022 Biggs Family Prize in Poetry for Black Sugarcane, her first book. She lives in Te Matau-a-Māui Hawke’s Bay.

Te Herenga Waka University Press page