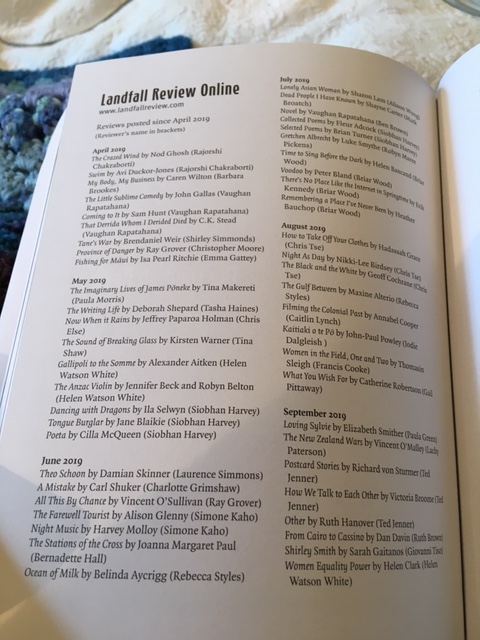

Summit, Thomson Gorge Road (looking towards Mount Aspiring).

Photo: Gregory O’Brien, October 2025

Backcountry

Now and ever

the mountain river.

A fantail flits.

Moss over branch,

the trees hurry.

Undying stone

continues the rhyme:

there is no time.

Richard Reeve

from Generation Kitchen (Otago University Press, 2015)

At the end of September, Gregory O’Brien sent me the media release for an online fundraising art show he was curating.

Nine well-established New Zealand artists have gifted works to raise funds in opposition to the proposed Bendigo-Ophir gold mine in Central Otago. The artists – all strongly opposed to the open pit mine – have come together under the banner “No-Go-Bendigo”, and are offering 100% of the funds raised towards fighting the fast tracked mine. All have been deeply affected by the majesty and singular character of the region—as the statements on the exhibition website underline. They all wanted to make a strong stand.

Dick Frizzell, Enough Gold Already, 2025,

limited edition of 12 screenprints, 610 x 860mm,

The artists who have contributed are Bruce Foster, Dick Frizzell, Elizabeth Thomson, Eric Schusser, Euan Macleod, Grahame Sydney, Gregory O’Brien, Jenna Packer and Nigel Brown. The works they have gifted for sale can be seen here.

Exhibition organiser Gregory O’Brien, said that the group of artists from all over the country was highly motivated to help. “The proposed desecration of a heritage area for purely monetary gain is an outrage to all of us, as it is to the citizens of Central Otago and to all New Zealanders.” He said that the initial group of nine artists have already heard from other artists enthusiastic to help “during the next round”. “Painters, photographers, writers, film-makers, choreographers and other arts practitioners from within Central Otago and further afield are incensed at the churlishness of both the mining consortium and the Government’s ruinous ‘Fast Track’ (aka ‘Highway to Hell’) legislation. The environmental cost of such a cold-blooded, extractive exercise is simply too high, as is the social impact and down-stream legacy.”

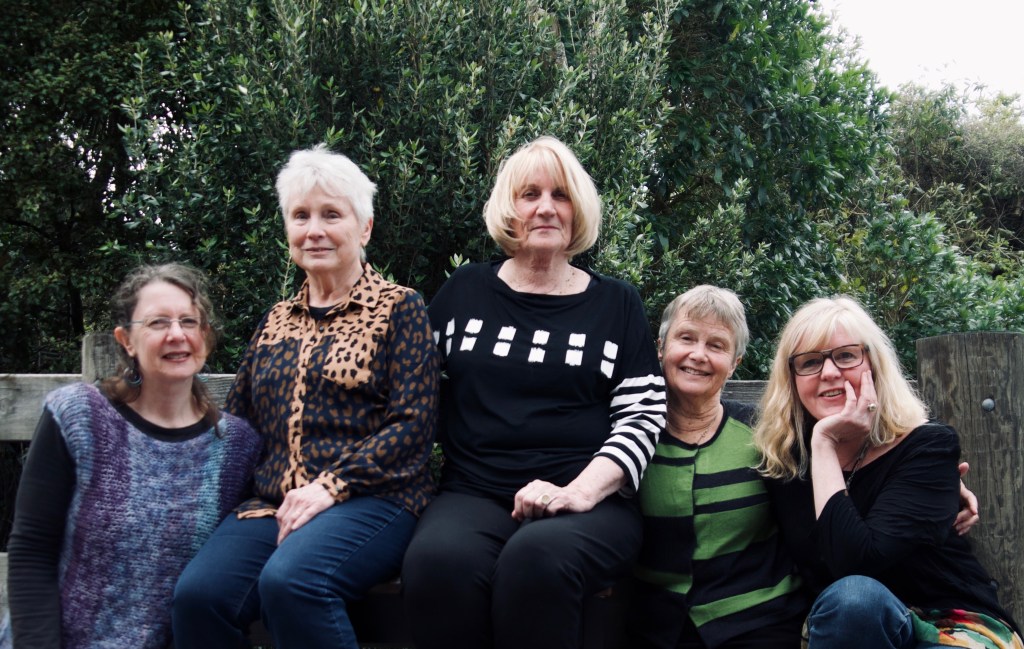

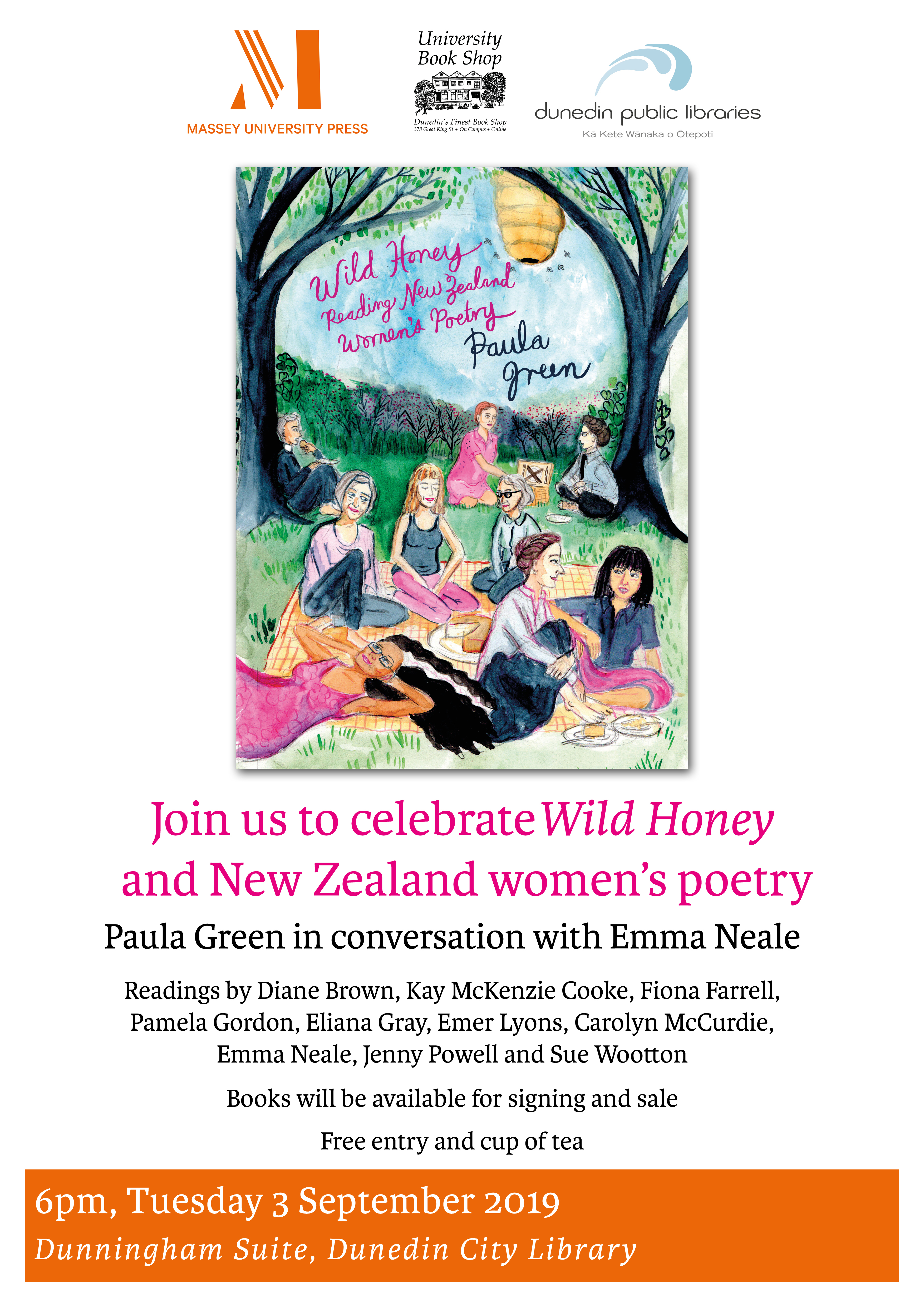

When Gregory said that this was just the beginning, at the end of the exhibition media release, I knew Poetry Shelf had to become involved. My new Poetry Protest series was the perfect opportunity – knowing that poetry speaks out and for and because of issues in myriad ways. Gregory, Richard Reeve and I invited a number of poets based in the area (and beyond) to contribute a poem. Jenny Powell’s poem catches sight of the Dunstan Range, David Kārena-Holmes has penned an aching lament, Emma Neale writes of her local blue swallows that can also be found near Benigo. And then there are poets with miners in the family history such as Jeffrey Paparoa Holman and Diane Brown. Twenty three poets have gathered on this occasion but there are so many poets in Aotearoa singing out in defence of the land. Some poets chose poems from collections, while others wrote poems on the spot, often out of anger and frustration.

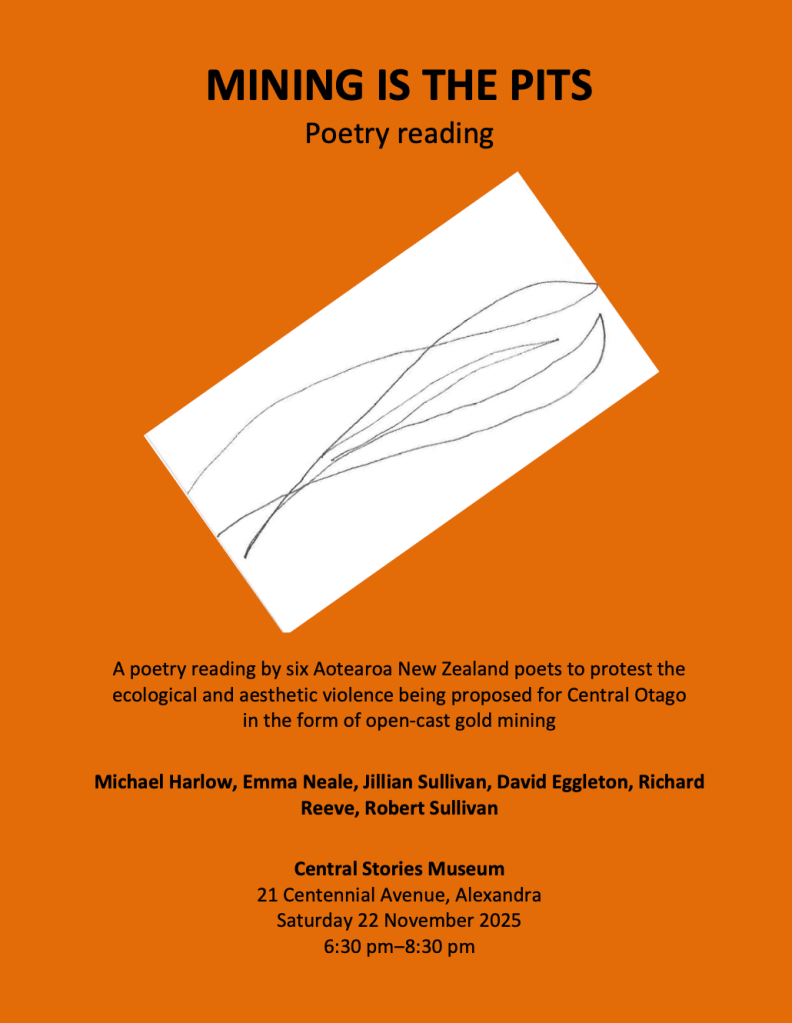

Richard Reeve, who is organising an anti-mining poetry reading in Alexandra in November (see poster), has written an introduction for the post. He sent me a suite of poems, both new and old, that touch multiple cords of beauty and outrage. I have included an older poem to head the post, and a longer new poem after his introduction. I have also included an extract from a recent media release by Sam Neill.

An enormous thank you to Gregory and Richard for co-curating this post, to all the poets who contributed, and to everyone who continues to read and write poetry. Today is a day of significant strikes by nurses, doctors and teachers in Aotearoa, a day with a major weather event still unfolding and widespread power outages, and the continuing heartslamming news from overseas.

To be able to connect with readers and writers who care, matters so very much, as I sit here weeping with a strange mix of sadness and gladness, beauty and outrage.

Thank you.

Thomson Gorge Road

Photo: Richard Harvey, October 2025

For Freddy – Ora pro nobis

A little while ago now, Lord Byron in his book-length poem The Prophecy of Dante mused, “Many are poets who have never penned / Their inspiration, and perchance the best”. By this he meant that even non-literary types can have poetic experiences. That of course begs the question, What do we mean when we talk about poetry? Is poetry, as some sceptics would suggest, purely prose with line-breaks, or does the concept embrace something more than words on a page to encompass the wider spectrum of lived experience?

Thomson Gorge Road in Central Otago is a place many would say has its own poetry, whether the subject of poems or not. A backcountry dirt road stretching from Matakanui near Omakau in the east to Bendigo near Tarras in the west, it cuts through a pass in the Dunstan Mountains that divides the Manuherikia Valley from the Upper Clutha Basin. Thomson Gorge Road is hawk country. Tussock country. The road is notorious for the sheer number of gates one has to open when using it as an alternative to the highway that skirts the base of the mountain range south to Alexandra and the Cromwell Gorge. The gates, livestock, steep winding track, stream crossings and mud mean Thomson Gorge Road is certainly not the fastest route from Omakau to Wanaka, even though more direct than the highway. Nevertheless, people travel it regularly enough.

Indeed, those who travel the road are off on an adventure. Punctuated with heritage sites associated with the colonial period (mine-shafts, abandoned huts, battery sites and so on), and before that significant to Southern Māori travelling the pounamu routes west to east, the passage exemplifies the interconnected complex of geophysical frontiers, native-vegetation-clad landforms and cultural touchstones that makes Central Otago uniquely important in our national psyche. The scenery is magnificent, encompassing in the course of the journey expansive views of two of the three great basins of Central Otago. Just as with the Hawkdun Mountains to the north or the Clutha-Mata-au River and Old Man Range to the south, Thomson Gorge Road is an essential component of wild Central Otago’s fabric, part of our collective heritage as a nation.

Despite this, flagged on by Minister of Resources Shane Jones and his “fast-track” legislative reforms, an Australian gold mining company – Santana Minerals – is now seeking permission to establish a giant open-cast gold mine not far from the crest of Thomsons Saddle, in an area situated within an officially designated Outstanding Natural Landscape and already subject to a conservation covenant. If consented, the base of the mine where huge volumes of tailings and toxic waste are to be stored will be only 6-7 kilometres from the Clutha-Mata-au River. In light of Minister Jones’ fast-track legislation, the general public have no right of input on the outcome of the proposal even though the open-cast mine is widely regarded as offensive, a public health risk and indeed a brutal and crass affront to the values of the region.

Those protesting the mine include not only poets and artists but also people who have no great interest per se in the literary arts or perhaps even the fine arts. Some have limited exposure to literature. Others likely know very little at all about Byron or indeed Cilla McQueen, Jillian Sullivan, Liz Breslin, Michael Harlow and others who have contributed poems to this edition of Poetry Shelf. Like the poets, they nevertheless understand intuitively and deeply that no amount of trumpeting by Santana or Minister Jones of the alleged financial value of the gold deposit will annul the violence being proposed to the fine poem – or fine wine, or fine painting, or good day on a bike – that is wild Central.

In this issue, Gregory O’Brien uses as an epigraph to his contribution, ‘Thomson Gorge Road Song’, Minister Jones’ now infamous comments to the effect that the days of deifying New Zealand wilderness are over:

We are not going to sit around and read poetry to rare lizards, whilst our current account deficit goes down the gurgler … If there is a mining opportunity and it’s impeded by a blind frog, goodbye Freddy.

Au contraire, Minister. In this issue we proudly dedicate poems to skinks, hawks, backcountry streams, tussocks, snow melt. We wilfully and without reservation pledge our heart and soul to Freddy. For, as Annabel Wilson asks in her poem ‘Gorge’, What would the real Santana – St Anna, mother of Mary – say? “Sancta Ana, ora pro nobis.” Pray for us, St Anna. God help us if we cannot as a people do better than this.

Richard Reeve – 20.10.25

Clutha Gold

People! Keep an eye on the prize before you. Emerging nugget,

the stuff “Black Peter” knew about, Bombay gentleman

who struck gold in 1857 at Tuapeka, scooping glinting gravel

from the riverbed with his cup years before Gabriel Read

saw flecks “shining like the stars in Orion on a frosty night”,

gold confirmed in Otago, a decade after New South Wales,

the glory – not to say reward – bestowed on the well-dressed candidate

(not the half-caste from Bombay whose honesty gave rise to no reward).

People! Keep an eye on the prize. Yes. The cycle trail we journey

in a meditative state, pausing to assess, for instance,

the scarification of the land above Beaumont Gorge,

native scrub scraped off just wherever possible given the steepness,

elsewhere, feral trees spilling out of the radiata along the tops,

sprouting under cliffs that once were waymarks to Māori

travelling up river from the coast along mahika kai routes.

If we are honest with ourselves, it is carnage. Chaos, plunder:

we ogle the fate of our kind who would move mountains

not far from here, nevermind scrub, in pursuit of the shiny stuff,

at so-called “Bendigo” in the Dunstan Mountains, Kura-matakitaki,

where men and women with geology degrees feverishly

calculate potential returns from the sparkling core samples

extracted under permit from the mountainback,

their CEO crowing future profits in the billions, regional growth,

speculation to accelerate the pulse of offshore investors.

Without cash, their fabled open-cast mine may not proceed.

Or it may. Certainly, the carnage we see from the riverbank

tells a story the trail people wouldn’t want us to focus on,

namely, the irrepressibility of our activity, humans in time

destined to be extracted from the view just like the mountains,

the land sliced up by farming, forestry, mining, infrastructure,

enterprise that in the end failed to save us from ourselves.

Those, at least, are the signs. What happens remains to be seen,

and we are getting ahead of ourselves. The end isn’t quite yet.

There is still sunlight and shadow, glitter of today’s fine day.

The prize is this deep blue vein of the motu, Clutha, Mata-au,

river that gave a pseudonym to Janet, a colour to Marilynn,

incrementally digging out its passage through culture,

resolving its way to the sea. We cycle from name to name,

past livestock, old gardens unravelling with age like memories,

derelict barns at the edge of paddocks, willow clusters;

the prize presumably is us, steering our contraptions

along the edge of a signature, at Beaumont saying goodbye

to the river, the trail now mostly following the highway,

gold country but no longer river country, dead Black Peter

ghosting the great disenfranchisements evident from the trail

as we ride through a converted landscape, sheep country

at Bowler’s Creek, pine plantations on the hills above Lawrence,

wholly transformed land, just riparian planting in the valleys

to give any indication of a time before now. The age of birds,

rivers, podocarps, sunlight, snow-melt, flax. Winking boulders

in which the ore retained its secret, faithful to the long moment

before our century of hard-hatted Ministers of Resources

tapping rocks and denouncing the catastrophe of the economy

(no mention of the slow-motion catastrophe of the land,

what is obvious all around us yet routinely overlooked

by those in rapid transit from name to name, place to place).

People! Anyway. Yes. Keep an eye on the prize before you,

we get that. And riding into Lawrence is certainly gold,

the sun setting on our handlebars, sheep laughing as we pass,

the fields outside town home to sun-drunk ducks, goats, horses,

good sorts in the only environment they have ever known,

lifestyle blocks, drained, fenced paddocks, previously bog

that before the man-driven fire was once primaeval forest.

Hard to believe, the gaudy general store on the main drag

now also extinct; also extinct the ironmongers, breweries, lions

that roamed the township, in its origins displaced by mining creep

to the present location. Not yet extinct the beauty of the town.

Rusted colonial rooftops pepper the view, seasoned by exotic trees.

Truth is, nature was always ahead of us. To the bitter end.

Whatever control any of us dreamed we had was an illusion.

Night colonises the shadows. Worn out, we pull up at the car.

We are the gift that keeps on giving, despite the prognosis.

Clutha Gold was awesome, we say. At the Night ‘n Day, we gorge.

And it is a fact, we are happy. Good work people! Keep it up!

Richard Reeve

TOXIC

It’s unbelievable, really. Unbelievable. Why would you visit this kind of environmental catastrophe onto a region that is thriving, that is in the midst of what many of us think of as a renaissance? The future of Central Otago lies in its bike trails, vineyards, cafes, in good farming practice, and a diverse and growing population of people, young and old, who genuinely care about the future of where we live.

All aspects of life in the province will be permanently affected by the toxic presence of a mine at Thomson Gorge. The initial mining proposal (and it will only get bigger, you can be sure of that) includes four mining pits, one of which will be a kilometre long and two or three hundred metres deep. All fouling our water, risking arsenic and cyanide pollution among other poisons. Don’t even mention the mad noise, the carbon, the ruin of our rivers, land and air pollution, the road traffic, the dust… the incalculable environmental cost.

Of one thing you can be certain: If the Thomson Gorge Mine goes ahead, there will be further mining proposals to follow. Watch out, Bannockburn. Watch out, Central. Remember this – ‘fast track’ can mean hasty and fatal mistakes.

Coming in here with their bogus claims, their invented figures (’95 per cent of the locals support the mine’– come off it!), these people should be ashamed. Those of us who love Central Otago are going to fight this. Because, make no mistake, this mine would be the ruin of our region, and importantly its future.

Sam Neill – 22nd October 2025

Near turn-off to Thomson Gorge Road, Tarras

Photo: Gregory O’Brien, October 2025

Reading Poetry to Rare Lizards

SONG FOR THE TUSSOCK RANGE

‘I will up my eyes unto the hills …’

– Psalm 121

Deep Stream, Lee Stream, Taieri River

and their tributary waters –

all your lovely water-daughters,

Lammerlaw and Lammermoor –

dear to me and ever dearer,

Lammerlaw and Lammermoor!

Deep Stream. Lee Stream, Taieri river –

where I wandered in my childhood

with a fishing bag and flyrod –

Lammerlaw and Lammermoor,

dear to me and ever dearer,

Lammerlaw and Lammermoor!

Deep Stream, Lee Stream, Taieri River –

let no profiteers deface these

windswept, wild, beloved places –

Lammerlaw and Lammermoor,

dear to me and ever dearer,

Lammerlaw and Lammermoor!

David Kārena-Holmes

AT WEST ARM, LAKE MANAPOURI

Tourists on tourist buses enter

‘The Earth’s Arsehole’* (blasted, grouted,

|as though the Earth itself were buggered)

to view the powerhouse in the bowels,

where all the weight of thunderous water

that once was the glorious Waiau river,

flowing freely South to the sea,

is prisoned now in pipes and turbines

to serve the mercilessness of man.

And so, it seems, the mythic grief

of Moturau and Koronae

(whose tears, in legend, filled this lake)

is vented in a cry transformed,

exhaled as an electric current

from generators underground,

to howl through cables strung on pylons,

gallows-grim, from here to Bluff.

Are we who turn on lights at evening,

or use the smelted aluminium,

exploiters of anguish, buggerers of the Earth?

David Kārena-Holmes

*The site of this power project was, in the construction period, known to the workers (as is, no doubt, commonly the case in such environments) as ‘The arsehole of the Earth’. Most, or all, of the the power has gone to supply an aluminium smelter at Bluff.

Swoon

Skylark ripples the edge of silence,

icy hollows mirror its hover,

lines of dry grass quiver.

Winter’s travelling light transforms

the field of shaded frost

to shallow melt, and then, again.

Mountains drift into distance,

curve in whiteness. On either side,

hills and sky swoon at vision’s end.

Jenny Powell

Leave the arthropod alone

I saw a centipede in the crack of a rock

flipped the grey shape to view the earth underneath, watched

tiny legs scurry to safety, skittering from my unwanted gaze

I found a story in the hem of my coat

picked it apart, ripping the seam stitch by stitch

till the torn fabric, this undoing, was all I could see

I peered through a telescope at the southern sky’s gems

winced at the big-man voice next to me, joking about ladies who covet

– if only we could own them, if a man would get them for us, we’d be happy

I light the quiet fire of this poem: a resilient critter, a seam

that holds, the sparkling truth lightyears from man’s reach – these things

shining in the untouched crux

Michelle Elvy

A Faustian Bargain

Can I speak as a descendent

of Cornish tin miners?

Hunger led them to flee

to Australia and Kawau Island,

where they survived and profited

in minor ways, digging up gold and copper.

None owned a mine, some died

of the dust, and in 1867

my great-great grandfather

died in a mine collapse

in Bendigo, Victoria

leaving a widow, and nine children,

one unborn. Is the tiny opal

in my wedding ring

handed down from him?

Can I speak, knowing nothing

of this heritage before I shifted south

and my husband took me

to the old schoolhouse site

in Bendigo, Central

where we camped on the hard dryland.

Born in Tamaki Makaurau,

in view of the Waitemata

I took time to love this new land,

the forbidding mountains, cold lakes

and rivers, shimmering tussocks,

and now vineyards and tourists

annoying as they may be

bringing a more benign form of riches.

Can I speak, knowing my ancestors

left their toxic tailings,

their dams of arsenic and lead

still poisoning the water

150 years later?

Too late for apologies or compensation,

the best I can do is speak up,

say, beware these salesmen

with their promises of jobs,

and millions to be made.

Once the land is raped,

its gold stored safely in a vault

for nothing more than speculation,

the money men will walk away

leaving land that feeds no one,

water that will slake no thirst.

Diane Brown

An Anti-Ode to Mining in Central Otago

There’s Lord Open Cast, pompous in yellow smog.

Corporate blokes raise another hair of the dog,

and pump more pollution for the water-table.

Dirty dairying brings bloody algal bloom;

so much cow urine until nitrogen’s poison,

that the arse has dropped out of the rivers.

Yes, the day looks perfect with road tar heat;

gorsebush fires flame above the lakeside beach.

Spot mad scrambles of rabbits gone to ground,

as orchards totter and grape-vine soils erode;

while every avenue is twisting itself around,

looking for the fastest way out of town.

Roadside lupins in Ophir echo purple sunsets.

Bendigo’s carbon offerings are burnt by nightfall.

A hundred per cent pure express their distance,

when smell of decayed possum chokes the air.

Don’t let land’s dirge be your billy-can of stew,

the petrol reek of your tail-finned septic tank.

Tailings will anchor environs turned unstable.

Once hymns were sung to hum of the tuning fork,

as the ruru called out, Morepork, morepork;

now drills hit post-lapsarian pay-dirt,

just where Rūaumoko rocks an iron cradle,

and the raft of Kupe fades to a roof of stars.

They would mine hills hollow because earth shines gold.

Clouds packed in sacks, a bale-hook making way.

Hear creeks burble and croon in violin tones,

over lost honey-thunder of long-gone bees.

Join the boom and bust of prize pie in the sky;

chase lizards of rain running down bulldozed trees.

David Eggleton

The Underside

Under the house the dust is dry

as an archaeologist’s brush, stippled

by the motionless rain of those particulars

that make our bodies, my body

groping, stooped and short-sighted,

under the loom of joists and time.

In this lumber room of mothlight

and clotted webs are countless lives

burrowing down and flitting between.

There is a workbench, joyously scarred.

There are bedsprings for sleeping bones.

There are scaffolding planks, rusty bricks,

the cheek of the hill that holds us up.

There is fire and there are stars

beneath this upturned palm

on which the piles of our home tremble.

And beyond, the astringent glory

of brindled hills that calls me to dwell

on the underside: this drowning-fear

that has us scrabbling up the ladder

of never enough, forgetting the ground

it foots upon. This lapse in listening to

the depositions of the earth.

Megan Kitching

nothing to do with you

For a cup of coffee,

you would strike the heart

with an axe, mine stone

for its marrow.

Maim

what rolls on into sky. Screw

metal poles into quiet land,

warp and crush

its offer

of light and air.

*

For greed,

on whenua

nothing to do with with you,

you would trammel

quilted, southern ground, leave

a trail of stains,

thrust twisted iron

nto its soft belly.

*

Rocks the wind or sun

cannot move, sleep on.

Tussock-backed

they carry soft gold

sound

we can hear for miles.

From somewhere,

a farmer

calls his dogs. Somewhere

the blaring throats

of young bulls

we cannot see.

Under our feet the gravel

coughs. Fallen apples

form a wild carpet

below a crooked tree.

*

The mist freezes

where it wafts, solid

lace. Cold, bloodless

and beautiful. Still for days

on end, the sun a smear

across the sky’s white mouth.

Bulrushes stuck fast

in frozen ponds.

Willows and poplars

as wan as horse-hair.

*

In summer, the grasshopper

screams. In summer

the road floats

grey. Purple lupins

and orange poppies

dribble paint.

When we stop the car

we hear overhead

a pair of paradise ducks,

their alternating cries

the unfenced sound

of a mountain tarn.

*

Seized by the sun,

valleys do not resist

the line and fall

of riverbeds and trees.

On whenua

nothing to do with you, somewhere

the sound of a tiny bird.

Somewhere, lovely light,

the sound of nothing, of no one,

of the air.

*

Kay McKenzie Cooke

This poem, ‘nothing to do with you’, differs slightly from the original published in the book Made For Weather (Otago University Press, 2007).

Burn

It’s Brian Turner rolling around in the bed

of a dry burn. Ghost poet

Brian Turner galloping the fence line, hunched over a hockey stick.

Brian Turner, order of merit,

spectral at a precipice,

rubbing scree in his beard.

Brian Turner opens his mouth and out comes the roar of the sun.

The broom fries.

The hawks microwave.

Ghost poet Brian Turner teleports up and

kicks at the plateau with a heel.

To the living, the clouds are invisible.

But, squirting over stones, the skinks have

Brian Turner’s tiny eyes.

Tussock have his hands, the wind

his keys.

The hilltops had hoped to be rid of him.

And they are.

Nick Ascroft

Otago: A Ballad (golden version)

Another golden Aussie

in his big golden truck,

crossing the water

to try his golden luck.

Rips up the golden tussock.

Digs a golden hole.

Finds a lot of rock

and a bit of golden gold.

While Shane and all his buddies

stand around and cheer

in a land called Desolation.

No vision. No idea.

But they take their golden pennies,

buy a house, a car, a yacht.

And they sail away

on a plastic sea,

to nowhere you

would want to be.

On this barren rock

they’ve scraped blood red,

trashed and burned

and left for dead.

Leaving us nowhere to run.

Circling round and round the sun.

Ripped out our heart.

our breathing space.

This golden land

that was our place.

Fiona Farrell

Mine

i.m. Pike River miners 19 November 2010

Son, there was a time when you were mine

Brother, when the shining day was ours

Friend, there was an hour when all went well

Darling, for a moment we were love

Father, you were always close at hand

Human, we were people of the light.

And now, the mountain says ‘he’s mine’‚

And now, the rivers say ‘he’s ours’‚

And now, the darkness says ‘my friend’‚

And now, the silence says ‘my love’‚

And now, the coal says ‘father time’‚

And now, we wait for the day to dawn.

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman

from Blood Ties, Selected Poems (Canterbury University Press, 2017)

This is something of a raw topic for me, given my background as a miner’s son, growing up in a mining town. I’ve just looked in my copy of Blood Ties, Selected Poems, from 2017, and there is a section there with twenty poems related to mining and miners, much of it related to my growing up in Blackball. There are three poems there that speak to Pike River, a sore wound at the moment, with the film’s premiere in Greymouth last night. I have a family member who could not face going. Her father died in the Strongman Mine explosion in 1967, when nineteen miners lost their lives. JPH

The Blue Language

In our local park, five welcome-swallows

swoop and dart for midges, their red chests

swell as they sing their high, sky dialect;

the thin vowels in their lyric glint as if rung

from glass bells blown in South Pacific blue.

The quintet shifts, leans in the italics of speed:

moves now like mobile acrostics,

now a faithful, swaying congregation

every bone adoring air

until an unseasonal despotic wind

flings them out of sight —

scatters twigs, dirt, smashed tail-light, laundry, leaves and newspapers

like those that reported how, across Greece,

thousands of migratory swallows dropped

on streets, balconies, islands and a lake,

small hearts inert

as ripped sheet music.

In our throats, the wild losses dilate,

squat like rock salt

in a browning rose

a grief clot, untranslatable.

Emma Neale

Note: There is a shadow of the phrase ‘the green language’ here; also known as la langue verte; in Jewish mysticism, Renaissance magic, and alchemy, this was a name for the language of birds; often thought to attain perfection and offer revelation. Also see ‘High winds kill thousands of migratory birds in disaster over Greece’, Guardian, April 2020.

Is the whole world going into Mutuwhenua?

I’m looking at No Other Place to Stand (te whenua,

te whenua engari kāore he tūrangawaewae)

and it gets me wondering about the end

of the whole blimmin’ world. Blimey.

What will I do then? Can’t swim in ash.

Can’t plant akeake. Can’t eat mushrooms

like our tūpuna, the ones that grew

on trees and used for rongoā,

or practice as children on gourds

the tā moko tattoo patterns of our tūpuna

with plant juices from tutu and kākāriki

(pp. 98–100 of Murdoch Riley’s Māori Healing

and Herbal). Soot from kauri was rubbed

into tattoos to make them black forever.

Robert Sullivan

from Hopurangi / Songcatcher: Poems from the Maramataka (Auckland University Press, 2024)

E hoa mā, please buy No Other Place to Stand: An Anthology of Climate Change Poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand Edited by Jordan Hamel, Rebecca Hawkes, Erik Kennedy and Essa Ranapiri (Auckland University Press, 2022)

Mining Lament

I went to see the golden hill

but it had all been mined away

all that’s left is an empty bowl

of yellow gorse and rutted clay

But it had all been mined away

except a clay bluff topped with stone

in yellow gorse and rutted clay

one stubborn relic stands alone

Only a clay bluff tipped with stone

remains of the hill the painter saw

one stubborn relic stands alone

of a rounded hill of golden ore

Remains of the hill the painter saw

rutted clay and a stumbling stream

a rounded hill of golden ore

sluiced away with a sluicing gun

Rutted clay and a stumbling stream

all that’s left is an empty bowl

sluiced away with a sluicing gun

I went to see the golden hill

(after a painting by Christopher Aubrey, c. 1870 of Round Hill, Aparima, Southland)

Cilla McQueen

from The Radio Room (Otago University Press, 2010)

Thomson Gorge, Gregory O’Brien, Oct 2025

Old Prayer

Hawk, as you

lift and flare

above the river’s

slide, take us not

in thy talons. Take us not

from the bank

or branch or wrench us

from the earth, lifted by

calamitous wings.

Fix us not with your eye.

Take us not up

the way you raise the sparrow

and the finch. Leave us

as the covey of quail

in the willow.

Leave us be.

Jenny Bornholdt

from Lost and Somewhere Else (Victoria University Press, 2019)

Gorge

Somewhere

in deep time, this collection of

chemical / isotopic / insoluble

composition signatures rises

and falls —

and falls —

falls —

rises

No one still, silent surface

along this space

in this intense South,

Gwondwana: floods, grey-washed

avalanches, rumbling glaciers, slips

hot water rushing through cracks

engorging crystalline schist

with veins of quartz

layers of platy mineral grains

{ graphite, pyrite, arsenopyrite }

Variations roaring through endless seasons

myriad manifolds must melt

surfaces scrape

gales salve

escarpment creep

alps keen, pine, take

Glaciers loose from time

Ice must, is—

grey, weathering—

heat, rousing—

Mata Au quickening—

Give, heave, cleave, groan

water milky blue, rock particles

scattering sunlight beginning and beginning and

Fast track to hammer / / Fast track to tamper \ \ Fast track to “explore”, drill, dredge, bore / / Fast track to gorge gorge gorge \ \ Fast track to contamination / / Fast track to hollowed out \ \ Fast track to haunted / / Fast track to dust \ \ Fast track to coarse-veined lies / / Fast track to nowhere \ \ Fast track to what would the real Santana, St Anna, say? / / / Sancta Ana, ora pro nobis.

Annabel Wilson

a suitable machine for the millions

for/after Hannah Hayes

forge and smithy

durability before cheapness

do the work of a dozen men

colonise

settle, spin the wheel

first cost, last cost, stop

the machine

if necessary check

up press and guard before

you start up

all cut, all shaped

all mannered the same two

tubes snug

one turns another

turns one turns a way

to make

it work invention

is the mother on two

wheels

and everything

is material or it is

immaterial

floating, dust

between us

Liz Breslin

from show you’re working out, (Dead Bird Books, 2025)

Stone

After all, stones remember

the opening and closing of oceans

the thrust of volcanoes; they remember,

in their sediments, ancient creatures and trees,

rivers, lakes and glaciations.

After all

stone is the firmness

in the world. It offers landfall,

a hand-hold, reception. It is

a founding father with a mother-tongue.

You can hear it in the gravity

of your body. You can hear it

with the bones of your body.

You can hardly hear it.

See that line of coast…

See the ranges ranging…

they seem to be

saying

after you,

after you,

after all…

Dinah Hawken

from Ocean and Stone (Victoria University Press, 2015)

Māori Point Road, Tarras

You and not I, notice the change in light at this time. On my side, it’s all busted

rough-chewed grass, stink of silage, black bulls in drenched paddocks. Rusted

mailboxes punctuate the long gravel line. Drenched sheep. We are haunted

by the chortle of a trapped magpie, the Judas bird made to betray. The black glove comes down once a day.

On your side, twilight bathes paddocks Steinlager green, all the way to those

wedding cake Buchanans, the white crown in the distance. The human need to

see shapes in things: a rock that looks like a wing. We carry on, not speaking.

We carry on not speaking. You know I want to ask you something.

Annabel Wilson

Substratum

We are so vulnerable here.

Our time on earth a time of

how to keep warm and how to be

fed and how to quell our most

anxious thoughts which come back

and back to connection.

How do we stay here on this earth

which is right below our feet?

Soil, clay, substrates of rock,

magma, lava, water, oil, gas;

the things we want to bring up and use,

the things we want to use up.

If all we ever wanted was to know

we would be warm and fed and listened to,

would we be kinder?

Would we in turn listen? Would we understand

the importance of those close to us

and the importance of what is under us?

We have the far sight. And we are what

the shamans warned against.

Jillian Sullivan

Previously published in Poems4Peace, Printable Reality

Deserts, for Instance

The loveliest places of all

are those that look as if

there’s nothing there

to those still learning to look

Brian Turner

from Just This (Victoria University Press, 2009)

Ōpawaho Heathcote River

As a child we fished and swam the Ōpawaho

Now Ōpawaho is muddy full of silt

unswimmable unfishable for days after rain

as cars leach poisons, some factories spill metals,

subdivisions and farms without 20 metre wide riparian plantings spread,

as shallow rooting pine forests get blown and burn

Opawaho’s waters grow thick with mud sediment and poisons

For our tamariki to swim and play safely in our river

we want 20 metre wide riparian plantings on each side of any stream or creek flowing into the awa

where the awa flows muddy we can plant raupo

build flax weirs to stop sediment with holes to let fish through

lay oyster shells on the river floor

Any other ideas let us know

Ōpawaho pollution is our mamae pain

Her harikoa joy brings smiles to the faces of our people

Her rongoa healing restores our wetland home

Kathleen Gallagher

Great Men

(after Brecht)

‘Great Men say dumb things.’

And then they do them.

When that plumped-up someone

is trying to talk to you about themselves

and they are using ‘fat word’ you can be

sure they are as spindle-shanked in heart

as anyone can be. ’The dumbness of their

third-rate ideas’ not even a tattered wonder.

And you know that whenever they are

smooth-talking about peace, they are preparing

the war-machine. Just to show you how dumb

they really are, they keep talking to each other

about how they are going to live forever.

Michael Harlow

from Landfall 243, 2022

Poet’s note: Bertolt Brecht was a Poet, Playwright, and Theatre Director. He was renowned for The Three Penny Opera, and his most famous plays Mother Courage and Children, and The Caucasian Chalk Circle. His most famous quotation: ’Terrible is the Temptation to be Good’. As a Marxist and Poet he was noted for his social and political criticism.

Thomson Gorge Road Song

“Those people who have sought to deify our wilderness … those days are over. We are not going to sit around and read poetry to rare lizards, whilst our current account deficit goes down the gurgler… If there is a mining opportunity and it’s impeded by a blind frog, goodbye Freddy”. (Shane Jones, Minister of Resources, May 2025)

Stand me a while

in this warming stream then

stay me with flagons, apples—

the sustainable industries

of each numbered morning. Or bury me

in arsenic, in heavy metals,

blanket me in blackened earth

and scatter my ashes

beside the Mata-Au,

in the bright orange of its contaminated

flow. Bury but do not forget me

under what was once

a greenwood, then lay that ailing tree

to rest beside me. Steady

and sustain me, streets

of the noble town

of Alexandra, strike up

your municipal band and

bring on the blossom princesses

of early spring. Forget if you can

this season’s toxic bloom.

Bury me in sodium cyanide,

then set me adrift

as toxic dust, carry me high above

your ruined waters, your tailings.

Bury me

in spurious claims, the cheery sighing

of cash registers, volatile stocks

and the non-refundable deposits of a town

that goes boom. Lay me down

in bedrock and slurry,

in overburden and paydirt,

fast-track me to the next life.

Bury me

under the freshly laid asphalt

of Thomson Gorge Road

in gravel and aggregate—bury me there,

beneath your highway

to hell, but please don’t take me

all the way with you, Minister Jones.

Play instead this song on every stringed instrument

of the province: on the wiring of

O’Connell’s Bridge, each note

strung out on vineyard wiring

and well-tempered,

rabbit-proof fencing. Sing me this

open-cast, sky-high song

above Rise & Shine Valley,

bury me in the company of

the last native frog of Dunstan,

the last attentive lizard,

lay me to rest, this once quiet road

my pillow, sing me this song

but do not wake me.

Gregory O’Brien