Bill Manhire occupies a significant position in our literary landscape — as both a poet and as founder of the International Institute of Modern Letters. As poet he is lauded on an international stage and at home was recognised as our inaugural Te Mata Poet Laureate. As teacher and mentor at Victoria University, his outstanding contribution to our writing communities was honoured by the naming of the Bill Manhire House at IIML (April 2016). I have read Bill when he is not writing poems and have admired his clarity and elasticity of thought, but I had not read the early fiction in his recently released The Stories of Bill Manhire (VUP). Things escape us for all kinds of reason. In the 1990s, I focused on all things Italian as I wrote my doctoral thesis and missed too many local things. What a loss!

Amongst so many books I have loved, three books have really got under my reading skin in the last month: Cilla McQueen’s memoir, In Slanted Light, Tusiata Avia’s Fale Aitu, and Bill’s short stories.

Each of these books took me by surprise. Like little thunderbolts where you can feel your heart rate pick up as you read. Bill’s book didn’t cleave me apart like Kafka’s axe to the head or heart (he says the frozen sea within) but felt like the utterly satisfying thirst-quenching intake of sparkling water. Writing that is effervescent, clear, restorative. I guess that is doing something miraculous to your parched state (a different kind of frozen sea). This is what words can do.

To celebrate this book – a short review from me and an interview with Bill.

A wee review:

The stories in this collection are gathered from The New Land: A Picture Book, South Pacific and Songs of My Life. There are previously unpublished stories, The Brain of Katherine Mansfield where you choose your own adventure, and the memoir, Under the Influence.

The writing is inventive, refreshing, surprising, on its feet skipping kicking doing little jumps.

How can I underline how good it is? As I read my way into days of reading pleasure, I squirmed cringed gasped laughed out loud sighed did wry grins wriggled on the spot leapt over the gaps laughed out loud again and felt little stabs that moved.

The stories highlight place and character, become nostalgic with detail that glints of when we were young (well for me anyway). You might move from the Queen’s visit and telling jokes to a dog named Fairburn, to a sci-fi keepsake on the tongue, to questions and answers on writing, to a dead-end job. Yes, the subjects are captivating but it is not so much what the stories pick as a starting point but how they travel. Take any story and it is a rejuvenating read. ‘Nonchalance’ for example, is like a series of postcards, travel or writing tips; or arrival tips with love and broken heart, soldiers, soldiers’ wives and the locals. You enter a realm of first things and floating elements. The readerly effects are kaleidoscopic.

To give you a taste of the book (I hope this doesn’t ruin things for you), here are some of the first and last lines. So important in a short story – these just nail it.

First lines:

Some critics write me off as just another ghost character activist, whereas I think I add up to a lot more than that.

The bishops come ashore.

Through here?

You are just an ordinary New Zealander.

The poet looks at the poet’s wife and says: You are my best poem.

He says: ‘Give me something significant.’

A slight scraggy moustache.

There are many tricks I have used repeatedly throughout my career to date, and others that I have done only really as one-offs.

Last lines:

Like a gasping in the chest.

The paddocks are left grey, stretching out to the edge of the frame.

Clouds pour across the sky and my lungs fill with air as though they might be sails.

No.

But jokes are too difficult: I’m getting someone else for that.

God bless him, and all the other poets.

That is how it is, adventure and regret, there is no getting away from it, we live in the broad Pacific, meeting and parting shake us, meeting and parting shake us, it is always touch and go.

The ‘Ghost Who talks’ made me laugh out loud with all its literary references alongside or inside the tricky business of getting ‘you’ and ‘I’ active in a story. Ha! It felt like the pronoun ghost out stalking. Then again the playful absurdities in ‘Kuki the Krazy Kea’ made me squirm with its dry wryness. Or the magician’s performance tips. Head back to the stories at the start of the book and the bits that taste a little different: details of a nuclear winter, Ghandi’s funeral pyre, the melancholy of an empty pool, a mother colour-tinting photographs at the kitchen table. Bill enters the story to give writing tips here and there, to tilt the world a touch so you have to steady your reading feet (where next! What next!), to frame a judicious amount of missing bits, to be a little bit cheeky, to catch something provocative or lovely or poignant. This is a book I will recommend to friends.

A wee interview:

What satisfies you about writing a story?

Pretty much what satisfies me about writing a fully-functioning poem. There’s pleasure in the mix of surprise and inevitability, which needn’t be plot and character based. Sometimes it can just be a sense of musical completion.

I also like it if readers are given room to move and even a little work to do, and they end up feeling pleased about this, rather than grumpy. Maybe that’s explicit in The Brain of Katherine Mansfield, which is my shot at a choose-your-own-adventure story. But the best writing always invites readers to make choices as they go along. I’ve always liked Whitman’s take on the text-reader relationship: “I seek less to state or display any theme or thought, and more to bring you, reader, into the atmosphere of the theme or thought—there to pursue your own flight.”

Were there any rules you wanted your stories to obey? Or disregard? I love the way some of the stories sneak in instructions for start-out writers.

I think that by and large I’ve written against rules and tried to avoid what’s sometimes called the beige short story, of which the great exemplar is probably Joyce’s ‘The Dead’. Glorious stuff, but . . . well, Joyce didn’t want to go on doing it, did he? Mark Haddon was writing about beige stories in the Guardian recently: ‘modest, melancholic stories, not arcs with beginnings, middles and ends, so much as moments and turning points.’ I’m a big fan of melancholy, but you read too many stories like that in a row, quiet epiphany after quiet epiphany, and the whole world starts to feel a bit insipid.

I suppose those instructions for beginning writers represent a complaint against the formulaic. What I mean is this sort of advice, which comes from a New Zealand book called How to Write and Sell Short Stories published back in the 1958:

PLOTS TO AVOID

(a) Plots with a sex motif.

(b) Where religion plays a dominating role.

(c) Plots where sadism or brutality appear.

(d) Plots with a basis of divorce.

(e) Plots where illness or disease must be emphasised.

(f) Plots dealing with harrowing experiences of children.

(g) Plots dealing with politics.

And so on. Remove plots like those, and it’s hard to see what’s left. I’m generally quite troubled by short story writing manuals, and by creative writing workshops that behave like short story manuals.

I also love the detail that catapults the reader to specific times and places — how much did that sort of thing matter to you?

Getting the voice right in each case felt like the most important thing, and of course details are a crucial part of that. Quite a few of the stories are really dramatic monologues, opportunities to try out some other voice or personality. That’s most obvious when they’re written in first person, but also in a strange way it’s also there in close third person. The story called “Highlights” is third-person but it comes across in a flat, somewhat affectless voice – because it’s about a rather passive person. Anyway, the voice thing mattered to me, and I found myself trying on a range of idioms. I don’t think in general it’s a good idea to read a lot of short stories in a row, especially if they’re by the same writer, but I hope there’s quite a variety of narrating voices in the book.

Can you recommend some short-story writers?

There’s so much I haven’t read, but I’d go for Grace Paley every time. Also Donald Barthelme and Lydia Davis. Gogol is my greatest favourite, especially “The Nose”, which I was once able to read in Russian. Early Sargeson. Some of Ashleigh Young’s personal essays feel to me like beautifully told short stories – they just happen to be true, or true-ish. And the best of Barbara Anderson’s stories go on being brilliant – full of such sudden things. William Brandt’s collection, Alpha Male, has rather dropped out of sight, but it’s pretty fantastic – he does these wonderfully indignant, damaged narrators.

Do you have a favourite in the collection?

Probably “The Days of Sail”, though that may be because I know the back-story – it’s prompted by a covered-up assassination attempt on the Queen in Dunedin during the 1981 Royal tour. A 17-year-old took a potshot at her from the top of a Med School building in Great King Street. Imagine if it had been successful! Dunedin would be totally on the map! Anyway, I built a rather cranky story around that fact. There’s a nice radio adaptation that used be in the RNZ archive that I’d quite like to hear again. It ends with a children’s choir singing “God Defend New Zealand”.

Do you find endings difficult (I have to say I loved the endings!)?

Yes, they’re the hardest things. I think I manage to get them right most of the time – except maybe for “The Death of Robert Louis Stevenson”, which of course is obliged to end with his death. Not exactly a twist in the tail. Maybe the best ending is in “The Brain of Katherine Mansfield”. Or, I should say, endings. I’ve met people who feel quite put out by the apparently brutal instruction, “Close the Book”, which comes at the close of several of the plot strands.

But “The Brain” is also about white middle-class complacency and its right-wing tendencies – so there is a “real” ending, too. I won’t quote it, but anyone who wants to see what I mean can try to get to section 50 online, courtesy of Richard Easther and Jolisa Gracewood: I’d also advise readers to pause on Greg O’Brien’s illustrated section headings. There are lots of good visual arts jokes, along with a couple of depictions of C K Stead as a mad Nazi brain surgeon.

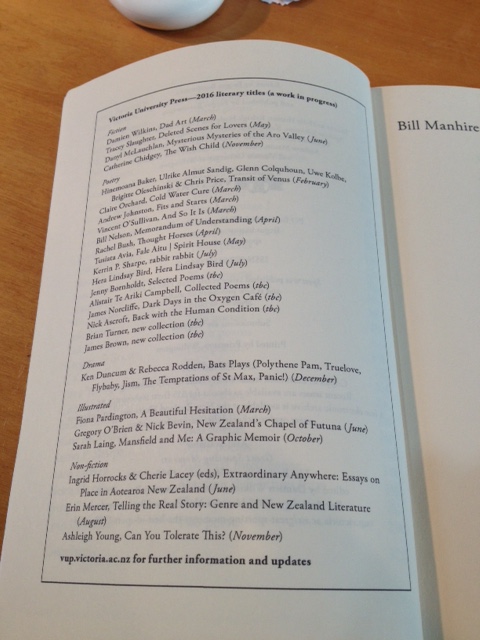

Victoria University Press page