Low Tide, Aramoana

Sky with blurred pebbles

a ruffle on water

sky with long stripes

straight lines of ripples

sky-mirror full of

sand and long pools

I step into the sky

the clouds shiver and disappear

thin waterskin over underfoot cockles here and there old timber

and iron orange and purple barnacled crab shells snails green

karengo small holes

I look up from walking at

a shy grey heron on

the point of flight.

oystercatchers whistle stilts and big gulls eye my quiet

stepping over shells and seaweed towards the biggest farthest

cockles out by the channel beacon at dead low tide

It’s still going out.

I tell by the moving

of fine weeds in

underwater breeze.

takes a time to gather these rust and barnacle coloured whole

sweet mouthfuls

Low.

and

there’s a sudden

wait

for the moment

of precise

solstice: the whole sea

hills and sky

wait

•

and everything

stops.

high gulls hang seaweed is arrested the water’s skin

tightens we all stand still. even the wind evaporates

leaving a scent of salt.

•

I snap out start back get moving before the new tide back

over cockle beds through clouds underfoot laying creamy

furrows over furrowed sand over flats arched above and below

with blue and yellow and green reflection and counter reflection

•

look back to

ripples

begun again.

Cilla McQueen

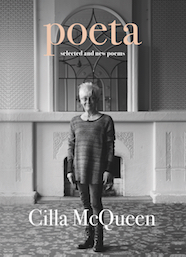

from Homing In (McIndoe, 1982), also published in poeta: selected and new poems (Otago University Press, 2018)

From Rhian Gallagher

Sometime in the early 1980s I heard Cilla read ‘Low Tide, Aramoana’ on TV. I was utterly spellbound.

Cilla does not so much read her poems as enact them. They seem written to a music score, a sound choreography. Her work is also very visual and ‘Low Tide, Aramoana’ is a big canvas.

Whatever expectations the title sets up are given a tilt at the outset. For it is not the tide that is encountered but the sky. It is a simple notion, the sky being reflected in the water, but I experience it in the poem as if it were a brand new thing and

‘I (too) step into the sky’

In more than one way ‘I step into the sky’. The tides are a condundrum, taking place on earth yet the movement is being conducted by the moon and sun. The spaciousness of the poem on the page has me feeling this mystery all over again — my mind is up there with the moon and the sun.

The meditative opening lines are followed by a hurried, heaped-up rhythm, detailing forms and life-forms encountered on the sand flats:

‘thin waterskin over underfoot cockles here & there old timber/& iron orange & purple barnacled crab shells snails green karengo small holes’

This alternating rhythmn shapes the poem. It is a movement from a contemplative interior to the external world and back again, flowing in and out, almost as a tide itself.

On one level this is a foraging poem: going ‘out to the channel beacon at dead low tide’ for ‘the biggest farthest/cockles’. Foraging is also a metaphor for the making of the poem: the gathering is going on right from the first footstep onto the sandflats and the poem is, indeed, made of ‘whole/sweet mouthfuls’.

Some decades past before I heard Cilla read this poem again, at the Dunedin Writers Festival. It was almost eerie. The poem has a tipping point. It takes us there, way out to the edge – a brink of change, when something amazing (or horrendous) is about to happen. That moment when ‘we all stand still’.

I may risk overloading the achieved simplicity of the poem. The environment it brings to life, the multiple invocations it sets going in me, is why it has stayed close. Cilla’s pared-down language and accessibility belies an underlying multi-layered sophistication. ‘Low Tide, Aramoana’ has never given up all its secrets.

— Rhian Gallagher

Rhian Gallagher‘s debut poetry collection Salt Water Creek (Enitharmon Press, 2003) was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for First Collection while her second collection Shift, ( 2011/ 2012) won the 2012 New Zealand Post Book Award for Poetry. Gallagher’s most recent work Freda: Freda Du Faur, Southern Alps, 1909-1913 was produced in collaboration with printer Sarah M. Smith and printmaker Lynn Taylor (Otakou Press 2016). Rhian was awarded the Robert Burns Fellowship in 2018.

Cilla McQueen is a poet, teacher and artist; her multiple honours and awards include a Fulbright Visiting Writer’s Fellowship 1985,three New Zealand Book Awards 1983, 1989, 1991; an Hon.LittD Otago 2008, and the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Poetry 2010. She was the National Library New Zealand Poet Laureate 2009 -11. Recent works include The Radio Room (Otago University Press 2010), In A Slant Light (Otago University Press, 2016), and poeta: selected and new poems (Otago University Press, 2018).