go here

If you were to map your poetry reading history, what books would act as key co-ordinates?

I couldn’t read as a child. I didn’t read a book till I was 20. My father read me all sorts of crazy stuff. However, I did read poetry. Because it was short and the sounds were wonderful. I read Keats and Shakespeare and the war poets very young, maybe around ten. It’s slow music, really, poetry. I had no idea what many of the words meant. I liked the beat, the rhythms and the small stories of those poems. I remember carrying little poetry books around everywhere, like they held some secret. And they did!

Around that time my mother sent me to an old woman in Avondale for elocution lessons. My mother thought I was swearing too much! ‘Ain’t’ and ‘not never’ etc. Old Mrs Davy was paid to ‘straighten me out.’ Huh! What she did was teach me the beauty of reading poetry, aloud. She made The Highwayman provocative and wild and fun!

C.K. Stead and Allen Curnow were milestones too, because they read to me at university, and made poetry go beyond the page into a life. And Riemke Ensing because she was wildly passionate, and she unpicked poetry like my father ate flounder; sucking the juice around every small bone.

Later I found a seductive freedom in the voice of Hone Tuwhare’s No Ordinary Sun – in Jenny Bornholdt and Paul Muldoon, and Simon Armitage’s Seeing Stars. Check out his poem, Song – perfect beauty.

What do you want your poems to do?

I guess I write to see and hear more about the world I’m in, to be surprised and bear witness to its wonders. I want these poems to be true to their geography, and their people.

When I wrote Walking to Africa, I wanted the poems to stand tall and be loud, and tell the world that adolescent depression is Shit!

In this Large Ocean Islands sequence I want the poems to go beyond the cliché of Pacific Islands, beyond the beachside resorts, to their stronger, truer and older heart.

Which poem in your selection particularly falls into place. Why?

For me each poem is loaded with the story of its writing, and the wider events that surround it. ‘Large Ocean Islands’ is part of a bigger work in progress, and I’m still being challenged to balance the whole, and to give each poem its place and an integrity of its own too.

‘The White Chairs’ is the ‘oldest’ poem of the sequence. You could say it belongs.

UNDRESSING THE LIVES OF THE SILENT HEROES

ADORNED IN SPECTACULAR SUNLIGHT

In reply to C K Wright’s The Obscure Lives of Poets; Revelation lives on a large ocean island

Three serve time in New Zealand. Two in fruit canneries

where golden peaches become the names of their children; Queenie

and Bonnie, who is really Bonanza. One mama brings a nectarine

stone through airport customs in her underwear. Another time,

between two breasts of Kentucky Fried Chicken. Neither flourish.

One thousand roosters with insomnia. One survives the storm that takes

his only son, spends his days in view of the sea, much of it riding.

The sound of one mango falling. Three named after the fathers

of the fathers of monolingual seafarers who came ashore, and left

behind narrow eyes and a new mode of cranial wiring. One of ten

is taken and becomes one of fifteen, unrelated; family ties mapped

back to uplift and shift and fire. One too many three legged dogs.

One joins the police because he believes he can take his dog to work.

One walks around Avatiu harbour at night looking for stars

that have slipped their leash, fallen into the sea. He will be there

to rescue them. One family, the size of fifteen islands connected

by ocean currents. One dances in the lagoon, waist high

in blue, and bouncing for the effect it could have on his waistline,

but only after sunset, and only on the neap tide. One big family.

One maintenance man is sent to prison for acquiring money

that did not belong to him. He has a penchant for high

performance running shoes and real diamonds.

One teaspoon of pawpaw seeds alleviates diarrhoea, and maybe hook worm.

One hands a machete to his son, says just get on with it boy,

not meaning the taro patch or the elephant grass or the palm fronds

hanging over the windows, pulling a blackness over his house.

One Ian George painting is not enough; one stone turtle on the rough grass.

One stays on even after his wife and kids leave, sleeps on a mat

on a friend’s deck, till the mosquitos find him, and immigration says

there is a fine for that sort of behaviour. One wave after one wave.

One island is all one needs to join the dots. One small paradise

emerges in the path of the old navigator, and sets the scene

for growing silent heroes in spectacular sunlight.

There is no blueprint for writing poems. What might act as a poem trigger for you?

I remember Jenny Bornholdt saying how a poem’s form finds itself in the writing, and I think that’s true. In Cyclone Season, the unrelenting heat and the way it lingers for weeks here, triggered a list of observations, repetitive and often banal.

Every day I write ‘stuff’ on my phone. Anything. Sometimes I’m amazed how something so ordinary here is spectacular, and starts a chain of surprise and insight. Like seeing a man at the lagoon at dusk with two small turtles in a tub of water. Watching him later taking them out swimming with him, like they were his children.

Poems are like vehicles; they have doors and windows, and they take you places.

Listening and watching, closely, ruminating, tasting, breathing them in – and sometimes being courageous – that triggers poetry.

If you were reviewing your entry poems, what three words would characterise their allure?

I’m not sure I am seeking to be ‘alluring’ in the poems I write.

In Large Ocean Islands I’d like the reader to see the wonder of the Cook Islands, and honour it. Each small island is big, and delicate and vibrant, and heavy with old wisdom. Sometimes I get a glimpse of something here that is so far removed from where I come from it feels like I’ve moved in time to what ‘we’ were before consumerism and capitalism and industrial economies. There’s a deep truth and a beauty here, that’s both joyous and heart-breaking.

You are going to read together at the Auckland Writers Festival. If you could pick a dream team of poets to read – who would we see?

Seamus Heaney, Robin Hyde, Yehuda Amichai Hone Tuwhare … OK, not a ‘real’ dream then? So many great poets to choose from! Let’s go with… Selina Tusiatala Marsh, Chris Tse, Tusiata Avia, Glenn Colquhoun …

Jessica Le Bas has published two collections of poetry, incognito (AUP, 2007) and Walking to Africa (Auckland University Press, 2009), and a novel for children, Staying Home (Penguin, 2010). She currently lives in Rarotonga, where she works in schools throughout the Cook Islands to promote and support writing.

The Starlings

Anger sang in that house until the scrim walls thrummed.

The clamour rang the window panes, dizzying up chimneys.

Get on, get on, the wide rooms cried, until it seemed our unease

as we passed on the stairs or chewed our meals in dimmed

light were all an attending to that voice. And so we got on,

and to muffle that sound we gibbed and plastered, built

shelves for all our good books. What we sometimes felt

is hard to say. We replaced what we thought was rotten.

I remember the starlings, the pair that returned to that gap

above the purple hydrangeas, between weatherboard and eaves.

The same birds, we thought, not knowing how long a starling lives.

For twenty years they came and went, flit and pause and up

into that hidden place. A dry rustle at night, fidgeting, calling,

a murmuration: bird business. The vastness and splendour

of their piecemeal activity, their lives’ long labour,

we discovered at last; blinking, in the murk of the ceiling,

at that whole cavernous space filled, stuffed like a haybarn.

It was like gold, except it was more like shit and straw,

jumbled with their own young, dead, desiccated, sinew

and bone, fledgling and newborn. Starlings only learn

a little thing, made big from not knowing when to leave off:

gone past all need except need, enough never enough.

Tim Upperton

from A House on Fire, Steele Roberts, 2009

Sarah Jane Barnett:

Since I first read Tim’s poem, it’s been my favourite by an Aotearoa writer. When I was a kid living in Christchurch, a hive of bees lodged themselves in our bathroom’s exterior wall. We could see them go in and out through a tiny hole in the stucco concrete. They’d land, pause for a moment on the hole’s lip, and disappear into the hollow. Eventually my parents had them fumigated.

There is so much to admire in Tim’s poem – the vibrating yet unpretentious language; the gentle comparison he creates between the labour of the family who ‘gibbed and plastered’ and the labour of the starlings’ ‘bird business’; his use of the collective noun, ‘murmuration’. I recommend listening to Tim read the poem to really see how good it is.

For me, the emotion of the poem comes from the family trying to ‘muffle’ the starlings. It makes me think about growing up in a house where ‘anger sang’ but was never acknowledged, and the way a child will push their fear and feelings down by concentrating on something else: starlings for example, or bees.

Sarah Jane Barnett is a freelance writer and editor. Her poetry, essays, interviews and reviews have been published in numerous journals and anthologies in Aotearoa and internationally. She has two poetry collections: A Man Runs into a Woman (finalist in the 2013 New Zealand Post Book Awards) and WORK (2015). Her poems often inhabit the lives of others, and ask how we find connection and intimacy when affected by trauma. Her essays explore the multifaceted theme of modern womanhood. Find out more here.

Tim Upperton’s second poetry collection, The Night We Ate The Baby, was an Ockham New Zealand Book Awards finalist in 2016. He won the Caselberg International Poetry Competition in 2012 and again in 2013. His poems have been published widely in New Zealand and overseas, and are anthologised in The Best of Best New Zealand Poems (2011), Villanelles (2012), Essential New Zealand Poems (2014), Obsession: Sestinas in the Twenty-First Century (2014), and Bonsai (2018).

Photo Credit: Sophie Davidson

If you were to map your poetry reading history, what books would act as key co-ordinates?

My poetry reading history – by which I mean paying attention to poetry and seeking it out on my own terms – begins with Anne Carson, whose long poem “The Glass Essay” was introduced to me by Anna Jackson in my final undergraduate year of uni. Her translations of Sappho in If Not, Winter and her shadowy, hybrid work Nox suddenly split open for me the limits of what poetry could mean. That’s when I began to feel at home in poetry, maybe because I’ve always been drawn to things that can’t be explained.

Very quickly in my literature degree I realised that the ‘Western literary canon’ we studied was the product of a violent colonial legacy. Instead I felt a pull towards the fringes of contemporary poetry, where I found poets doing extraordinary things with poetic form and linguistic boundaries, especially in The Time of the Giants by Anne Kennedy, The Same as Yes by Joan Fleming, and Lost And Gone Away by Lynn Jenner.

But it wasn’t until I discovered Cup by Alison Wong during my MA year that I recognised something of my own childhood and background in New Zealand poetry. Loop of Jade by Sarah Howe, published in 2016, was the first poetry book I ever read by someone half-Chinese like me. Ever since, I’ve been building my own poetry canon made up of works that negotiate displacement, loss, diaspora, living between cultures, and the ongoing damage caused by European colonisation. Schizophrene by Bhanu Kapil, Citizen by Claudia Rankine, Whereas by Layli Long Soldier, and Poukahangatus by Tayi Tibble are all books that I would like to carry around me at all times like talismans to keep me safe.

What do you want your poems to do?

I want a poems that are spells for curing homesickness, I want poems that are notebooks and witness accounts and dream diaries, I want poems that create a noticeable shift in the temperature of the air and transport you to your grandma’s kitchen.

Which poem in your selection particularly falls into place. Why?

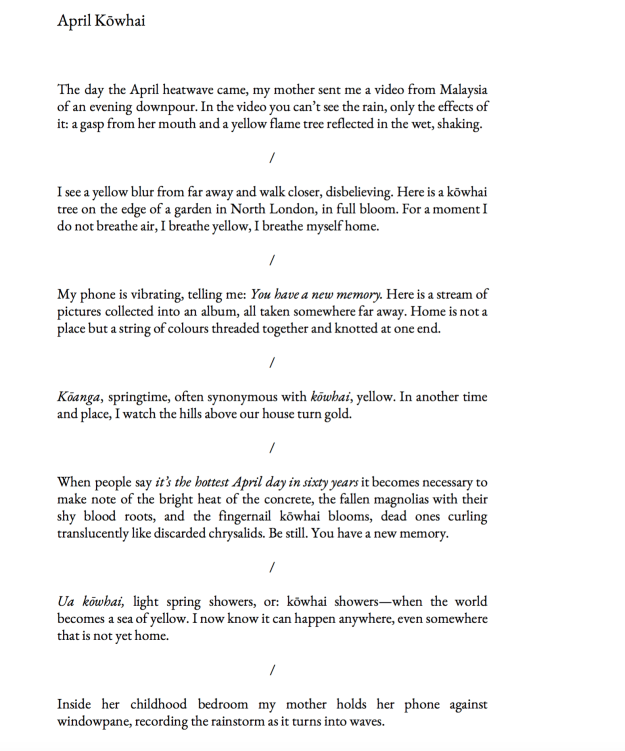

I knew that when I saw a kōwhai tree in full bloom in a garden in north London, close to where I was working at the time, I would need to write about it because it was the only thing I could do. It was spring and in spring I tend to feel really melodramatic about things. I don’t think the poem is melodramatic, though; I think it ended up somehow capturing what I was feeling, in fragments: both very far away and very close to home at exactly the same moment.

There is no blueprint for writing poems. What might act as a poem trigger for you?

Recent poem triggers: silken tofu, being near the sea, tracking sunlight across my tiny garden in order to figure out where particular plants will grow, a house on fire by the side of the motorway, chocolate ice cream, dreams about whales, Chinese supermarkets, reading, reading.

If you were reviewing your entry poems, what three words would characterise their allure?

(This is too difficult and I wish I could ask someone else). Dreamlike, downpour, heatwave.

You are going to read together at the Auckland Writers Festival. If you could pick a dream team of poets to read – who would we see?

It would have to be a few American and British poets who I’ve discovered only since moving to London, because I want them and their work to travel as widely as possible. But I wouldn’t want to read alongside them because then I would be too nervous / too in awe / tearful to listen properly. Ocean Vuong – because sometimes at poetry readings he bursts into song. Also Tracy K. Smith, Raymond Antrobus, Bhanu Kapil, and Rachel Long.

Nina Mingya Powles is of Pākehā and Malaysian-Chinese heritage and was born in Wellington. She is the author of field notes on a downpour (2018), Luminescent (2017) and Girls of the Drift (2014). She is poetry editor of The Shanghai Literary Review and founding editor of Bitter Melon 苦瓜, a new poetry press. Her prose debut, a food memoir, will be published by The Emma Press in 2019.

You can hear Nina read ‘Mid-Autumn Moon Festival 2016’ here

Owen Leeming, Through Your Eyes: Poems Early and Late Cold Hub Press, 2019

Owen Leeming has a fascinating bio on the back of his new poetry collection: he was a radio announcer, briefly studied musical composition in Paris, lived in London, published his poetry in various English magazines, became a UNESCO expert in Africa, settled in Provence, was the first writer to receive the Katherine Mansfield Menton fellowship (1972), joined Club Med in Spain where he met his future wife, worked as a translator for the OECD in Paris. He has remained based in France. His debut poetry collection, Venus is Setting, was published by Caxton Press in 1972.

This new collection is in debt to a trip back to New Zealand with his wife, Mireille but also assembles earlier poems from previous visits home. David Howard endorses the book, likening it to a vessel with two masts (the poems ‘Sirens’ and ‘Khalwat’) that set sail from Owen’s classic poem ‘The Priests of Serrabonne’. That poem was first published in Landfall in 1962.

Owen travels across four decades worth of fascinations, anchors and connections to place, people and ideas. The poems offer deft musical keys, lapping and lilting like little oceans, an undulation of consonants and vowels, assonance and rhyme. The sequence of physical returns form an elastic stretch between homes – France and Aotearoa. The poems often act as surrogate translations as though Own is translating his country of birth for Mirielle but also, and equally importantly, for himself transplanted at a distance. As he says in the terrific opening poem, ‘Crossing the Tasman’: ‘A sea still flows and Morse / messages stutter from a place you still call home.’

In a book that offers a measured pace, an attentive ear and evocative images, the opening poem is my favourite poem:

Bracing yourself against your life, you gaze

across ten years’ chop and swell:

That water widens still from then to now,

from home to now—(but where is home?)—sprays

on bitter wind the rail, your knuckles, eyebrow

and eye, pouring between your past (…)

Ruth Hanover, Other Cold Hub Press, 2019

Ruth Hanover, with a degree in English and a background teaching ESOL to refugees in Cairo, Stockholm and New Zealand has published a collection born of this experience, along with the experience of travel and years in therapy. Her poems have been published in London Grip, a fine line, takahē, Poetry New Zealand and Manifesto Aotearoa: 101 Political Poems (Otago University Press). Her poem, ‘The Tent’ gained the Takahē Poetry Prize 2017 and a new work was longlisted in the Peter Porter Prize in 2019.

To be reading the collection in the wake of the Christchurch terrorist attacks is to be acutely aware of certain issues. What do we mean when we say ‘we’ or ‘us’ or ‘them’, for example? To what degree should we voice the lives, pains, joys of others? Ruth’s book is dedicated to ‘the seekers of asylum and for those who reach towards them’. It is a timely arrival as we grapple with tragedy and how to reach out and indeed how to speak.

Ruth’s poems are not a matter of speaking on behalf of but a speaking towards, a speaking out of imagining, placing light on dislocations, violences, deprivations, catastrophes, inhumanity. They poems are written along a pared back line, with exquisite economy, as a sequence of voices, other voices – perhaps imagined and perhaps experienced – speaking from real situations.

I had gone in for oranges early persimmon —

the lush fruit the abundance. Behind me

‘but Europe — the réfugees did-you-see?

‘They were everywhere

The reply. The tone. I turn unstable

unable to bear the weight

of the oranges drop them drop

them in among the persimmon feel —

complicit as if I had committed

some act. (…)

from ‘The oranges’

We move from Nauru to Syria to Paris to Stockholm. We move with refugees, with the displaced and, as I move as reader, I feel other. Moved yet motionless in my state of privilege. I feel the helpless slap of what I can do in the face of intolerance.

Poetry can be the occasion of listening; Ruth offers subtle melodies in her finely crafted poems but she also offers other points of view. Both melody and viewpoint employ gaps on the line, fragments, with punctuation adrift to underline the difficulty of speaking of catastrophe. With an alluring blend of grace and sharpness, ease and discomfort, I can’t wait to see what else Ruth writes.

Victoria Broome, How We Talk to Each Other, Cold Hub Press, 2019

We are quite separate in this big house. Nana is a

good cook but she doesn’t hug, it’s hard to know

what makes us such companions. I think there are

things we know about each other we don’t know.

A bit like the mysterious chemistry of placing

flour and butter and eggs and sugar into a bowl

and then an oven and then a plate and then a mouth.

from ‘Nana in the Upstairs Bedroom’

Victoria Broome has published poems in literary journals and anthologies, was awarded the CNZ Louis Johnson Bursary (2005) and has twice been placed in the Kathleen Grattan Award (2010, 2015). How We Talk to Each Other is her debut collection.

The poems in How We Talk to Each Other arc over ten years, drawing upon familial experience, particularly memories of her parents, hooking the luminous detail that has endured. Poetry becomes a family imprint and like Ruth, Victoria pares back a scene until it shines. Big events are viewed on the fringes; how the young child witness feels, what she does, the glinting physical detail.

Victoria’s collection shows so beautifully the power of domestic poetry – poems that connect at the level of family – to slip under your skin and stay.

Sunnyside

Grandad went to the Mental Hospital

when we were in Wellington, he made us

sheep’s wool slippers, mine were royal blue

they came in a brown parcel in the post.

Then on a Sunday Mum got a phone call.

I heard her cry, ‘Oh no, oh no.’

At first she said, ‘He had a heart attack.’ The Dad said, ‘No,

he killed himself in the garage, he drank some poison.’

I aw the Irish Peach tree by itself at the back of the long yard.

Mum flew down and cleaned out the house. Nana came to stay.

I wore Mum’s rage, she chased me round and round the house

screaming while Nana stood with her hands up to her face.

Some nights I went riding on the train in the dark lit up by the yellow

light of the carriages, past the harbour to the city and then back again.

I stopped when Dad said I’d be made a ward of the state.

This book filled me with a warm glow – yes poetry can do anything and can affect us in so many vital ways, including the discomfort I felt reading Other – but on some occasions the deft translation of life, of everyday goings on, the view out the window, the family behaviours along with the losses, the absences, the deaths – produces poetry that is like a gold nugget. I need this. It restores me, it nourishes me, it reminds me that in poem empathy we witness humanity.

Owen Leeming Cold Hub Press author page

Ruth Hanover Cold Hub Press author page

Victoria Broome Cold Hub Press author page

Scotland Unfree

Two hundred long winters and thirty forbye

Have narrowed to nought since you first were unqueened, —

When cold, cunning usury made you the teind*

To Empery’s coffer, black treason unweened,

Undreamed of where yonder your mightiest lie,

Scotland unfree.

But they hear, but they heave, blessed mounds on the heath,

That house their true clay for you, mourner and mother,

Mounded for God and for you, not another,

Hear the moor-sloganing, brother to brother,

Hear it from Orkney to Tweed and to Leith,

Scotland unfree!

Mother of martyrs, now hear ye the living;

Mother of makers, world-marches away,

Who set your high mark, in their bold hodden gray,

On masterless wild and blue, bounteous bay, —

Palms for your honour, brave air, but, the giving,

Scotland unfree!

Hear you the living that fare never forth

From your guerdonless thrift in the halted out-flowing.

Too long your life-river, all-hoping, unknowing,

Gold-ribboned the seas from the dawn to down-going

Of sums that had set for your cradling North.

Scotland unfree.

Gold ribbons you gave to the seas of the west.

The world had your best of divine discontent.

Your parasites battened; despoiled and forspent,

‘Twas the babes of your breast, ’twas your children that went;

No steading in life, and no anchor of rest,

Scotland unfree!

What now and what more, when the world is at halt? —

When winds of all destinies clash in the blue?

The gadflies of battles are stinging anew,

Meanly to risk, or unhallowedly rue,

The redeless old nations in fear and at fault,

Scotland unfree.

Redeless they gather, no nation are you,

Mother of sages, the seal on your lips,

The gyve on your arm, by dead havens of ships,

Silent, interned, and betrayed to eclipse;

Scarce a name, not a nation! Is Caledon through,

Scotland unfree?

Lure-word of sophistry, “Britain!” quo’ she,

Weaver of phrases—high word and poor favour!

Your peers they are bidden—jejune and a-waver,—

To brag and to bicker; what salt and what savour?

“Britain?” what Britain that’s wanting of thee,

Scotland unfree!

Scotia, North Britain, draw biddably nigh,

Re-born to the day, and for ever re-born,

To the mock of moor-purple and crackle of thorn,

Your hour of re-queening: come, preen and adorn!

For your fairings you have but to dance and to die,

Scotland unfree!

Dance featly and fair, for your lords would be pleasured.

Skirl to their fancy, the caber let fly;

There’s gold for the lifting and silver forbye;

But, redeless, quiescent, to-morrow you die,

When for ever of yours shall your glens be untreasured,

Scotalnd unfree.

Be done with the talking, let scorning be done.

Bid Britain be Britain; whose vassal be ye,

Druidess, Norna, and chrissom Culdee?

One in a triad blent, one, two, and three;

God’s in His heaven, and Albyn is one,

Scotland the free!

Riddle us fairly that triad of yore;—

Sisterly queens that for ever are twain,

Sisterly queens that have done with disdain,

En-sceptred in one at the gates of the main

Live you, so live you, or none shall live more,

Scotland the free!

* Tribute

Note from Jessie: At the date of writing, May 31st, 1935, no answer has been reported to the recent joint demand of Scotland and Wales to be granted immediate Dominion status. The position has become increasingly impossible under the conditions of this century. For fifty years Scottish Home Rule Bills have been introduced, talked out or thrown out. Now national feeling demands the full and only solution of an impossible situation.

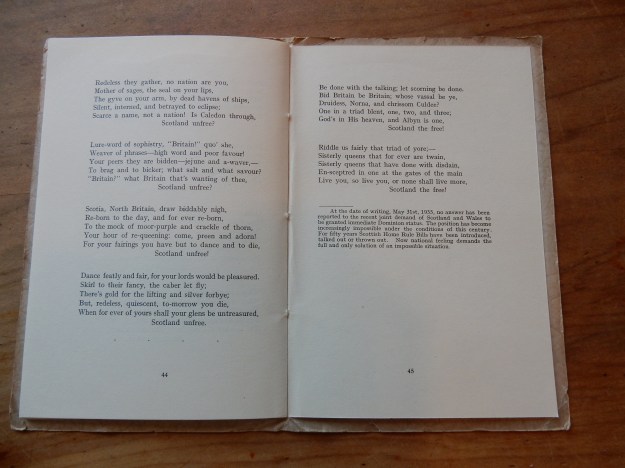

Jessie Mackay, Vigil and Other Poems, Whitcombe & Tombs, 1935

‘Scotland Unfree’ is the final poem in Jessie Mackay’s final book, Vigil and Other Poems.

Jessie Mackay (1864 – 1938) We have a poetry prize honouring Jessie Mackay’s legacy: the Jessie Mackay Best First Book Award for Poetry in our national book awards. Jessie was born in Rakaia, Canterbury and grew up on several remote sheep stations. She trained as a teacher, taught briefly and then devoted her life to politics and poetry. Jessie wrote countless letters to newspapers and articles on issues such as the plight of women, the vote for women, prohibition, ending the war and Scottish Home Rule. The latter affected her deeply as her Scottish parents spoke of their beloved homeland and the cruel land clearances. Perhaps this is why she revealed such a concern for Māori issues in a number of poems: the fact that land, language, stories and culture make a people. To take them away is to dispossess them. Cruelly. Unforgivably. Pākehā might write poems differently now, after decades of interrogating colonialism; perhaps less likely to borrow myth but, like Jessie, many poets are showing history in a new light (such as Parihaka). Jessie often drew us to the women’s point of view.

Towards the end of her life over 300 admirers presented Jessie with a testimonial letter that praised her outstanding humanitarian work and contributions to New Zealand literature. On her death the media sung her praises yet you are hard pressed to find her work in anthologies and we have no Jessie Mackay in print. When I first started reading her work it felt like a foreign country but the more time I spent in the archives, and the more time I spent with her writing, the more she moved me.

The first chapter in my forthcoming book, Wild Honey: Reading New Zealand Women’s Poetry, seeks to draw Jessie’s poetry closer. I am moved by her political stamina and by her battle to be heard as a woman writing. I have picked one of her Scottish poems to post as it feels very timely. What would she think? What would she think about Brexit and our own local tragedies? She would be weeping with her feet in the southern stream, and she would be speaking out. She would be writing poetry.

My book is out in August with Massey University Press.

This year’s poetry finalists in the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards will be appearing at the Auckland Writers Festival Award event: Tuesday 14 May, 7 pm- 8.30 pm, ASB Theatre, Aotea Centre.

The finalists: Helen Heath, Therese Lloyd, Erik Kennedy, Tay Tibble

This is an occasional series where I invite a group of poets to respond to the same question. First up: Why write poetry? I selected this question because a number of writers have mused upon the place of poetry when facing catastrophes that devastate our human roots. I pondered that question. I then asked myself why I have written poetry for decades regardless of whether it is published or applauded. It is what I love to do. It is my way of making music and feeling and translating and being happy no matter the life challenges. I also feel poetry is thriving in Aotearoa; at all ages, in multiple forms and in myriad places, many of us are drawn to write poems.

Albert Wendt

I write poetry because I can’t stop doing it: it demands that I do it, and it is ‘language’ that I feel most passionately about. When I’ve deliberately tried not to write poetry, I’ve ended up feeling unfinished, incomplete. When the poetry is shaping itself well in my tongue and throat, I feel healed, and healing.

Emer Lyons

I talk too much. A male Irish poet visited last year and said my poetry had none of the “jerkiness” of my personality. In writing poetry I find silence and the ability to give that silence space. After drinks with two men from the university last week, the one I had just met sent me a message on Twitter to ask me if I, like him, had Borderline Personality Disorder. Speaking in non sequiturs is not nearly as convincing as writing in them. As women, there are expectations about how we should speak, how we should take up space, how we should be more silent, more stable. Writing poetry is a minor release from social constraints, and the voluntary application of others. I can bind my breasts and write sonnets. On the page, I can be enough.

Erik Kennedy

I write poetry for the same reason that architects draw up concepts for floating cities: 1) to see what a better future might look like before it is possible, 2) to make the blueprints of progress public so that others can avoid making the mistakes that I have.

Therese Lloyd

Poetry remains mysterious to me. It’s such a strange beast and to be honest, sometimes I wish I had been bitten by the fiction bug instead. But I’ve been writing poetry for a long time. I think the first poem I ever wrote was when I was about 6. The poem was about fireworks and I remember the last line was “beautiful but dangerous”. Even at 6 years old I had a dark turn of mind! It may be a total cliché, but for me, poetry is a way to figure out how I feel about something. Writing poetry, especially that first thrilling draft, is an exercise in bravery. I love the feeling of having only the slightest inkling of what might appear on the page, and then to be surprised (sometimes pleasantly) by the string of lines that emerge.

Why write poetry? Because it’s confounding and liberating in turn. Because, as Anne Carson so famously says:

It is the task of a lifetime. You can never know enough, never work enough, never use the infinitives and participles oddly enough, never impede the movement harshly enough, never leave the mind quickly enough.

Michele Leggott

Why write poetry? To sound distance and make coastal profiles, to travel light and lift darkness. I go back to what I wrote about these and other calibrations: A family is a series of intersecting arcs, some boat-shaped, others vaults or canopies, still others vapour trails behind a mountain or light refracted through water. None is enclosed, all are in motion, springing away from one another or folding themselves around some spectral inverse of the shape they make against sea or sky.

essa may ranapiri

I write poetry because I love what poetry can be and can do. With poetry you can create these rather dense language objects that have the ability to confront many realities very quickly without sacrificing complexity. It is a space where I feel the English language can be at its most decolonised and queer and wonderful. And it also a space I feel most comfortable exploring the language of my tīpuna te reo Māori, a language I have only really just started learning. Poetry’s capacity for fragmentation and error, gives me permission to try out who I am and who I want to be. It also encourages in me a radical imagination about the society we live in and the societies that we could live in. A poem can be built in a day and take years to understand, it can both encapsulate and be the moment. A poem can give people who are marginalised a space to really embody their voice, make the air vibrate with their wairua, and in so doing provide an opportunity for community for those that struggle to find it wherever they are.

Bernadette Hall:

Why write poetry? Why not write poetry? Why should a poem choose you to be its vehicle? ‘Poetry is a terminal activity, taking place out near the end of things’ wrote John Berryman in a review article in 1959. I feel a great excitement when I read his words. An enchantment. Since childhood, I have been immersed in language that’s not my own. In fact it’s dead. Or so the old school rhymes used to say about it, about Latin. And every now and then, a kind of ‘speech’ would emerge, in my native tongue, English, well out of the range of my everyday talking, things I would write down on paper. Secrets. Janet Frame has been quoted apparently as saying that her writing wasn’t her. Which would give you a huge amount of freedom, wouldn’t it, that embracing and distancing at the same time. Berryman went on to say of poetry, ‘And it aims …at the reformation of the poet, as prayer does.’ The re-formation. No wonder I’m hooked.

Cilla McQueen

It seems healthy for thoughts to have an outlet into the real world.

Thinking is in the poem and is the poem.

You attend to the material and the spiritual. You perceive humanity, see inside yourself and other people, listen to the language of insight, catch words from the deep layers of consciousness.

Writing something down in concentrated form is mental exercise. The elastic syntax inside language asks for attention and skill so that it can be used with subtlety, to contain many shades of meaning and feeling.

Writing is a pleasure. Whether it ends up as a poem or not doesn’t really matter.

Words can unblock. The complete absorption in writing, in silent concentration, can provide a psychic release. A poem both releases energy and generates it.

The act of writing can be a refuge and comfort, also a way of talking things out in order to understand. The page is always listening, a patient companion in times of solitude or loneliness.

Don’t know what I’d do without it. I’ve spent most of my writing life thinking about poetry, but am still wary of defining it (this is part of its charm).

♣

Albert Wendt has published many novels, collections of poetry and short stories, and edited numerous anthologies. In 2018, along with four others, he was recognised as a New Zealand Icon at a medallion ceremony for his significant contribution to the Arts.

Emer Lyons is an Irish writer who has had poetry and fiction published in journals such as Turbine, London Grip, The New Zealand Poetry Society Anthology, Southword, The Spinoff and Queen Mob’s Tea House. She has appeared on shortlists for the Fish Poetry Competition, the Bridport Poetry Prize, the takahé short story competition, The Collinson’s short story prize and her chapbook Throwing Shapes was long-listed for the Munster Literature Fool For Poetry competition in 2017. Last year she was the recipient of the inaugural University of Otago City of Literature scholarship and is a creative/critical PhD candidate in contemporary queer poetry.

Erik Kennedy is the author of Twenty-Six Factitions (Cold Hub Press, 2017) and There’s No Place Like the Internet in Springtime (Victoria University Press, 2018), and he selected the poetry for Queen Mob’s Teahouse: Teh Book (Dostoyevsky Wannabe, 2019). Originally from New Jersey, he lives in Christchurch, New Zealand. There’s No Place Like the Internet in Springtime is shortlisted for the 2019 Ockham and New Zealand Book Awards – he will be appearing at the Auckland Writers Festival in May.

Therese Lloyd is the author of the chapbook many things happened (Pania Press, 2006), Other Animals (VUP, 2013) and The Facts (VUP, 2018). The Facts has been shortlisted for the 2019 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards and she will be appearing at the Auckland Writers Festival in May.

Michele Leggott has published eight collections of poetry, most recently Vanishing Points (Auckland University Press) and has edited and co-edited a number of anthologies including the poetry of Robin Hyde.She was the inaugural Poet Laureate (2007-9) under National Library administration and in 2013 received the Prime Minister’s Award for Poetry. She founded the New Zealand Electronic zPoetry Centre and is professor of English at the University of Auckland. She recently contributed the introduction to Verses, a collection of poetry by Lola Ridge (Quale Press).

essa may ranapiri is a poet from kirikiriroa, Aotearoa and are part of the local writing group Puku. rir |Liv.id. They have been published in many journals in print and online, most recently in Best New Zealand Poems 2018. Their first collection of poetry ransack is being published by Victoria University Press in July 2019.

Bernadette Hall lives in a renovated bach at Amberley Beach in the Hurunui, North Canterbury. She has published ten collections of poetry, the most recent being Life & Customs (VUP 2013) and Maukatere, floating mountain (Seraph Press 2016). In 2015 shereceived the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Poetry. In 2016 she was invested as a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to literature. In 2017 she joined with three other Christchurch writers to inaugurate He Kōrero Pukapuka, a book club which meets weekly at the Christchurch Men’s Prison.

Cilla McQueen is a poet, teacher and artist; her multiple honours and awards include a Fulbright Visiting Writer’s Fellowship 1985,three New Zealand Book Awards 1983, 1989, 1991; an Hon.LittD Otago 2008, and the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Poetry 2010. She was the National Library New Zealand Poet Laureate 2009 -11. Recent works include The Radio Room (Otago University Press 2010), In A Slant Light (Otago University Press, 2016), and poeta: selected and new poems (Otago University Press, 2018).

Many years ago I was working two jobs to save to go overseas. One of these two jobs was an early morning shift in a coffee cart, just off Courtenay Place in Wellington, outside a building that housed corporates of many kinds. I worked at the coffee at cart with Jenny, who became a good friend.

Jenny was everything I thought going overseas would make me: effortless artistic, politically informed, culturally savvy. Her parents were both artists, and her uncle was once a Labour Prime Minister. Unlike me, she didn’t need to go overseas; she already knew about the world. In fact, when I told her I was saving to go to India, she just shrugged and said, sweet. No bravado, no interest in impressing. The opposite to me.

Jenny knew I was interested in poetry and that I’d been trying to write for a while. She knew I’d been reading people like Simone de Beauviour and Anaïs Nin, and that I carried this deep-seated belief that real life happened beyond these shores. Probably in France in the 1960s, but that didn’t stop me from going in search of it. Instead of challenging me on this warped idea, she simply slipped a beautiful cream paperback into my hands the day before I set sail; a parting gift. The book was 50 Poems: A Celebration, by Lauris Edmond. As if to say, there might just be some life here too.

I took Edmond with me in my rucksack, and together we would travel through India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and later, onto the UK, where I met up with Jenny in Glasgow some years later. I never said anything to Jenny, but even now, twenty or so years later, as I write this from my home in Dunedin, I still think about that parting gift and what it taught me.

There are several poems from this book that I have continued to come back to over the years. Including this one:

Epiphany

for Bruce Mason

I saw a woman singing in a car

opening her mouth as wide as the sky,

cigarette burning down in her hand

– even the lights didn’t interrupt her

though that’s how I know the car

was high-toned cream, and sleek:

it is harder for a rich woman…

Of course the world went on

fucking itself up just the same –

and I hate the very idea of stabbing at

poems as though they are flatfish,

but how can you ignore a perfect lyric

in a navy blue blouse, carolling away

as though it’s got two minutes

out of the whole of eternity, just

to the corner of Wakefield Street –

which after all is a very long life

for pure ecstasy to be given.

Lauris Edmond

Who was Bruce Mason, and why was Lauris Edmond writing a poem for him? More importantly, who was Lauris Edmond, and how could she write a poem that had the lines “the world went on/fucking itself up just the same,” in such close proximity to “Wakefield Street”? In my extraordinary naïvety, this poem took me by the hand and said: see, there are people here that think. Here was the poet, looking and noticing, thinking carefully, trying to understand, playing, slowing reality down a little … There was a form of existential enquiry happening in New Zealand, right under my nose — I’d just been too ignorant and ill-informed (and religiously adhering to a stereotype) to take notice. Which seems to me the whole point of the poem — there is stuff happening right in front of us all the time, we’re just too egotistic or preoccupied to see or hear it.

Lynley Edmeades

‘Epiphany’ is from 50 Poems: A Celebration (Bridget William Books, 1999) and was originally published in New & Selected Poems (Oxford University Press, 1991) and is posted with kind permission from the Lauris Edmond Estate.

Lauris Edmond (1924-2000) completed an MA in English Literature with First Class Honours at Victoria University. She wrote poetry, novels, short stories, stage plays, autobiography and edited several books, including ARD Fairburn letters. She received multiple awards including the Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship (1981), an OBE for Services to Poetry and Literature (1986) and an Honorary DLitt from Massey University (1988). Edmond was a founder of New Zealand Books. The Lauris Edmond Memorial Award was established in her name. Her daughter, Frances Edmond, and poet, Sue Fitchett, published Night Burns with a White Fire: The Essential Lauris Edmond, a selection of her poems, in 2017.

Lynley Edmeades is the author of As the Verb Tenses (Otago University Press, 2016), and her second poetry collection, Listening In, will be published in September this year (with Otago University Press). She is also a scholar and essayist, and currently teaches on the English program at the University of Otago. Her writing has been published widely, in NZ, the US, the UK and Australia.

Reception frame

the goose waddles

down the cobbled

sidewalk that leads

to the bath with

glass wings

it washes its pigeon

English and swallows

its honk to cluck like

a creole chicken

only the goose God

understands this

the rest of us

be silent.

stop gawking.

wait patiently.

light a warm fire

when the goose

is done

Mere Taito

Mere Taito is a Rotuman Islander poet and flash fiction writer living in Hamilton with her partner Neil and nephew Lapuke. She is the author of the illustrated chapbook of poetry titled, The Light and Dark in Our Stuff.

Ellen’s Vigil

Benjamin Isaac Tom

Passchendaele Ypres and Somme

three ovals float

on the cold wall

plastered whiter

than their bones,

young, khaki’d

their bud-tender eyes

premonition filled.

Ellen,

Her three boys gone,

transplanted seventy years

from Lurgan’s linen

no longer counts crops

in season

but digs diligently, delicately,

digs down

further down

her spade searching

her garden for

three lost sons

Thomas Isaac and Ben.

Lorna Staveley Anker

from Ellen’s Vigil Griffin Press, 1996

(The poem also appeared in The Judas Tree, 2013 and is published with kind permission from the Lorna Staveley Anker Estate)

I discovered the poetry of Lorna Staveley Anker in The Judas Tree, a selection edited by Bernadette Hall (2013, Canterbury University Press). The collection claims Lorna as New Zealand’s first woman war poet. She was born in Ōtautahi, Christchurch in 1914 and died in 2000. Her father died of throat cancer when she was two and her mother took in boarders to survive. Three of Lorna’s uncles were killed in WWI and her mother, Elizabeth suffered terribly. From childhood Lorna endured a lifetime of crippling nightmares, night terrors. She married Ralph Price Anker, a student she met at teachers’ college; they had four children and adopted a fifth. Lorna began writing and publishing in the 1960s, but her first collection, My Streetlamp Dances, did not appear until 1986. Two further collections appeared in her lifetime: From a Particular Stave (1993) and Ellen’s Vigil (1996). I so loved the posthumous volume, The Judas Tree, I reviewed the book on my blog.

Shortly after the review appeared, Lorna’s daughter, Denny, sent me a copy of Ellen’s Vigil and again the poetry resonated. Much later I found myself in the Turnbull Library doing research for Wild Honey and listening to various audio tapes. I was completely captivated by an interview between Lorna and Susan Fowke (from the Gaylene Preston Productions Women in World War Two oral history archive managed by Judith Fyfe).

There were many occasions when I was profoundly moved in the Turnbull and this was one of them. I was writing a book that engaged with the work of almost 200 poets and that required a very different focus to a book that considered a single poet or perhaps even ten. However sometimes a particular poet held my attention; I got lost in the maze and astonishments of unpublished writing, letters, interviews, diaries, scrapbooks. In Lorna’s case, to hear the poet speak was a special thing indeed. Gaylene has kindly given me permission to share some gems from Lorna on being a poet but I do encourage you to explore the oral history archive Gaylene has helped assemble.

♥

Lorna’s father sometimes wrote poetry, ‘particularly couplets’ for her mother and her mother ‘s meals ‘were a poem’: ‘she’d pickle nasturtiums and we’d have caper sauce with our mutton’. I can just picture the kitchen: ‘The shelves in the pantry would be shiny with rows and rows of goods.’

The poem ‘Ellen’s Vigil’ stems from the time Lorna’s grandmother went digging for her war-dead sons in her garden. Lorna said in the interview that her grandmother was ‘grandmother to all mothers and wives who had lost their beloved men – she was a symbol for me.’ Knowing this amplifies the ‘buried’ grief. Lorna had lived with her grandmother and grandfather for a period from 1921; her grandmother, we hear, had favoured imagination rather than ‘strict discipline techniques’.

Lorna suffered from an eye defect which hindered her reading but at the age of 52 she began writing: she said it was strange to have a slim reading history when then, at the age of 52, ‘out burst all this language and poetry’. In her introduction to The Judas Tree Bernadette muses on events that perhaps prompted Lorna’s poetry writing in the 1960s (the death of her son Staveley aged 21 and the fact his daughter was adopted out by the birth mother) and the way she began publishing after the death of her beloved husband (1983).

She recounts an incident where her poetry was rejected as middle-class rubbish: ‘I came home and I wrote out of indignation and rejection, passion, fury, disbelief, and it was the mildest poem the most restrained tender poignant poem about the death of affection’. Writing was often a physical thing for Lorna: ‘a fusing in my head’, ‘a rush of blood’.

Lorna shared a number of things on being a poet that stuck with me. She didn’t call herself poetic ‘but being poetic means you have a different print out’, and when you write poetry ‘your mind is going sideways’.

Lorna’s family helped publish her collections while Pat White, David Howard and james Norcliffe offered help and assistance with her debut collection. Two of her poems were published in Kiwi & Emu (1989) while Lauris Edmond selected her essay, ‘Has the Kaiser Won?’ for Women in Wartime (1986).

I recommend taking timeout in the archives and listening to the interview, tracking down Lorna’s individual collections and perusing the book that Bernadette assembled with such love and care. To return to the poetry with her autobiography, to remember the impact of war upon her well being and later her writing, to consider the way words flooded out when she was older rather than younger, is to enrich reading pathways through her work.

From my review of The Judas Tree

Lorna’s poems reflect a mind that engaged with the world acutely, wittily, compassionately. There is a plainness to the language in that similes and metaphors are sidestepped for nouns and verbs. These are poems of observation, attention, reaction, opinion, experience. The starting point might be the most slender of moments — and the poetry opens out from there, surprisingly, wonderfully.

In the first section (and indeed the largest section), war makes its presence felt; from the pain of departures, to the pain of the wounded, to the ache of loss. At times Lorna filters a poem through the eyes of her young self (for example, trying to make sense of Armistice Day). At times a concrete detail makes the poem more poignant (‘her spade searching/ her garden for/ her three lost sons’). In ‘Arie’s Tale’ the detail that renders the pain sharper is the ‘tyreless rims.’ In this poem the dead are carried away on a bicycle that makes such a clatter it is the hardest thing to bear (‘He felt it wasn’t respectful/ to his customers’). Lorna’s war poems stretch in all directions — they never forget the life that goes on and they never forget the heartbreak and loss that are etched indelibly. One of my favourite poems, ‘V.E.Day … and Neenish Tarts,’ moves beautifully between these two opposing but entwined forces. From the darkness of battle (now over), the poem moves to the grandmother dancing on the bed (as warm flesh weaves/ pink circles/ under a nightgown’; and from there to ‘Let’s have Neenish tarts for tea’ (this is cause for celebration). This first section of the book is a terrific addition to New Zealand war poetry because it casts a light on women at war (even when they remain in the kitchen).

‘Vision of Escape’, a poem by Lorna

Canterbury University Press author page