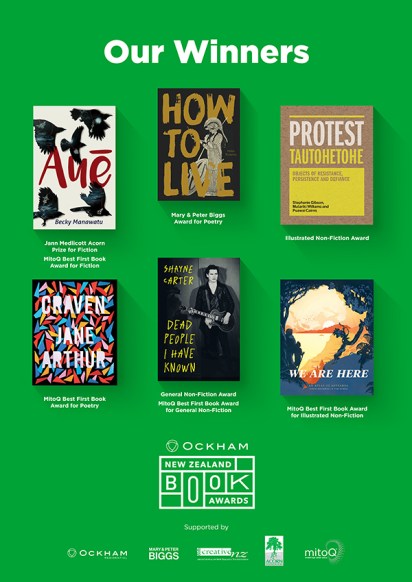

Warm congratulations to all winners! This is a year where well-deserving and much-loved books have taken the winning spots – each book is worthy of a place on our book shelves.

I look at this list (and indeed the shortlists) and it reminds me that NZ literature is in good heart. These are heart books. These are books born from love and labour, by both inspired and inspiring authors and publishers.

The Award’s poetry section was a drawcard for me. I loved each shortlisted finalist so much, but I leapt for joy at the kitchen table to see Jane Arthur win Best First Book and Helen Rickerby win Best Book.

Yes, some extraordinary books did not make the longlists let alone the shortlists – but this is time to celebrate our winners.

I toast you all with bubbles and bouquets and can’t wait to see what you write next.

Right now we need to support our NZ book communities, so I strongly advocate putting an Ockham winner in our pile, the next time we visit our local booksellers.

In these strange Covid times my email box has has never been so full of poems – we’re making sour dough and we’re writing poetry, and it has been such a connecting comfort.

Long may we cherish poetry in Aotearoa.

My toast to the Poetry Winners:

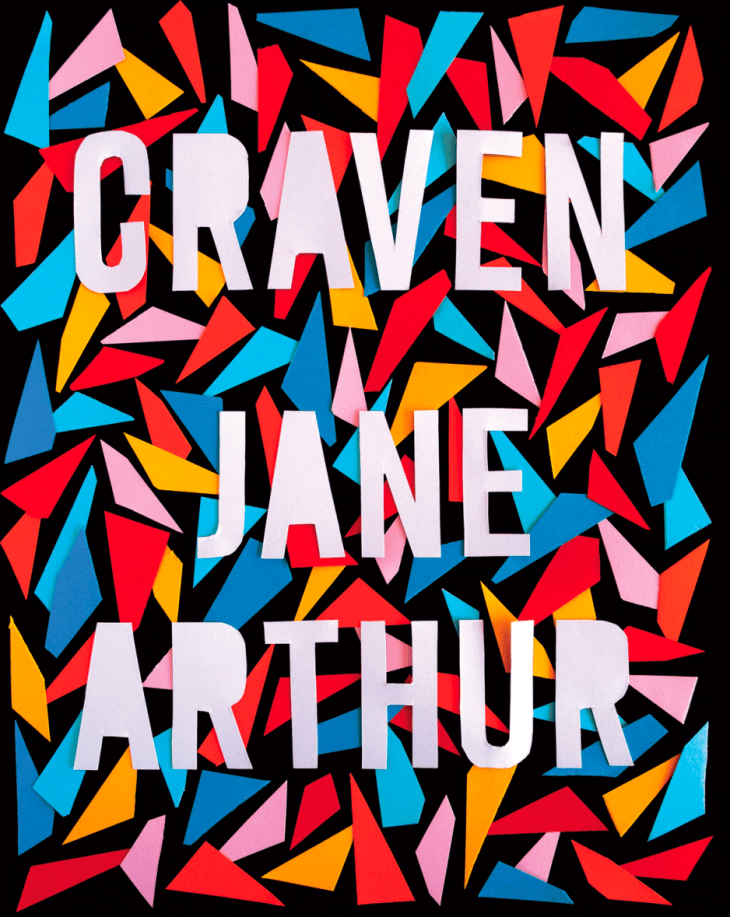

Craven, Jane Arthur, Victoria University Press, 2019 Best First Poetry Book

I have a broth at a simmer on the stove.

Salty water like I’ve scooped up some ocean

and am cooking it in my home. Here,

gulp it back like a whale sieving plankton.

Anything can be a weapon if you

swallow hard enough:

nail scissors, a butter knife, dental floss,

a kindergarten guillotine, hot soup,

waves, whales.

from ‘Circles of Lassitude’

Jane Arthur’s debut collection Craven inhabits moments until they shine – brilliantly, surprisingly, refractingly, bitingly. Present-tense poetry is somewhat addictive. With her free floating pronouns (I, you, we) poetry becomes a way of being, of inhabiting the moment, as you either reader or poet, from shifting points of view.

It is not surprising it has won Best First Book at 2020 the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

The collection title references lack of courage, but it is as though Jane’s debut collection steps across a line into poetic forms of grit. This is a book of unabashed feeling; of showing the underseam, the awkward stitching, the rips and tears. Of daring to expose. The poems are always travelling and I delight in every surprising step. You move from taxidermy to piano lessons to heart checks and heart beats, but there is always a core of exposed self. And that moves me. You shift from a thing such as a plastic rose to Brad Pitt to parental quarrels. One poem speaks from the point of view of a ship’s figurehead, another from that of Constance. There is anxiety – there are dilemmas and epiphanies. The poetic movement is honeyed, fluid, divinely crafted – no matter where the subject travels, no matter the anxious veins, the tough knots.

An early poem, ‘Idiots’, is like an ode to life, to ways of being. I keep crossing between the title and the poem, the spare arrival of words punctuated by ample white space, elongated silent beats that fill with the links between brokenness, strength and pressing on.

Idiots

I’ve known people who decided

to carry their brokenness like strength

idiots

I’m a tree

I mean I’m tall, I sway

I don’t say, treat me gently

No¾I say, cool cool cool cool

I say, that really sucks but I guess I’ll survive it

or, that wind’s really strong

but so are my roots, so are my thighs

my branches my lungs my leaves my capacity to wait things out

I can get up in the morning

I do things

I heard Jane read for the first time at the Sarah Broom Poetry Prize session at the Auckland Writers Festival in 2018. Her reading blew my socks off, just as her poems had delighted American judge, Eileen Myles, and it was with great pleasure I announced her as the winner. Eileen described Jane’s poetry: ‘poetry’s a connection to everything which I felt in all these [shortlisted] poets but in this final winning one the most. There’s an unperturbed confident “real” here.’ In her report, Eileen wrote:

The poet shocked me. I was thrust into their work right away and it evoked the very situation of the poem and the cold suddenness of the clinical encounter, the matter of fact weirdness of being female though so many in the world are us. And still we are a ‘peculiarity’ here and this poet manages to instantly say that in poetry. They more than caught me. I like exactly how they do this – shifting from body to macro, celestial, clinical, and maybe even speaking a little out of an official history. She seems to me a poet of scale and embodiment. Her moves are clean and well-choreographed & delivers each poem’s end & abruptly and deeply I think. There’s a from the hip authority that inhabits each and all of these poems.

I am revisiting these words in view of Craven’s multiple poetry thrills. So often we talk about the way a poem steps off from the ordinary and blasts your heart and senses, if not your mind, with such a gust of freshness everything becomes out of the ordinary. This is what happens with Craven. A sense of verve and outspokenness is both intoxicating and necessary:

I’m entertaining the idea of never being silent again,

of walking into a room and shouting, You Fuckers Better Toe the Line

like a prophylactic.

from ‘Sit Down’

A sense of brittleness, vulnerability and self-testing is equally present:

I’ve been preoccupied with what others think again.

I’ve been trying not to let people down.

Nights are not long enough.

Lately there’s been more sun than I would’ve expected.

I keep the weather report open in its own tab and check it often.

From ‘Situation’

The movement between edge and smooth sailing, between light and dark, puzzle and resolution, and all shades within any dichotomy you might spot – enhances the reading experience. This is a book to treasure – its complexities and its economies, its confession and its reserve. It never fails to surprise. I am delighted Jane read as part of my Poetry Shelf Live session at Wellington’s Writers Festival in March. It was a divine reading.

Victoria University Press page

Poetry Shelf Monday poem: ‘Situation’ by Jane Arthur

Poetry Shelf audio spot: Jane Arthur reads ‘Snowglobe’

Poetry Shelf: Conversation with Sarah Broom Prize finalist, Jane Arthur

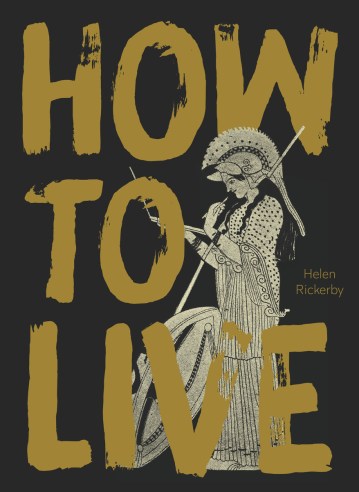

How to Live, Helen Rickerby, Auckland University Press, 2019 Best Poetry Book

Helen reads ‘How to live through this’

When that philosopher said life must be lived forwards

but can only be understood backwards

he was not thinking of me

I have lived all kinds of lives

from ‘A pillow book’

Helen Rickerby’s latest poetry collection How to Live is a joy to read. She brings her title question to the lives of women, in shifting forms and across diverse lengths, with both wit and acumen. Like many contemporary poets she is cracking open poetic forms – widening what a poem can do – as though taking a cue from art and its ability both to make art from anything and in any way imaginable.

Reading this book invigorates me. Two longer poems are particularly magnetic: ‘Notes on the unsilent woman’ and ‘George Eliot: a life’. Both function as fascination assemblages. They allow the reader to absorb lyrical phrases, humour, biography, autobiography, insistent questions. Biography is enlivened by such an approach, as is poetry.

6. It seems to me that poetry usually begins with the self

and works its way outwards; and the essay, perhaps, starts

outwards and works its way in towards the self.

from ‘Notes on the unsilent woman’

Thinking of the silent woman I am reminded of Aristotle’s crown of silence that he placed upon she. I then move across centuries to Leilani Tamu’s poem ‘Mouths Wide Shut’ where she sits on a bus with her mouth taped shut silent. The skin-spiking poem (and the protest) considers silence in the face of racism. Even now, even after the women’s movements of the 1970s and the explosion of feminism and feminisms over ensuing decades, men still talk over women, still dismiss the women speaking (take women in power for example, or a young woman at the UN challenging climate-change inertia).

What Helen does is remind us is that silence is like snow – it is multi-hued and deserves multiple names and nuances: ‘Silence isn’t always not speaking. Silence is sometimes / an erasure.’

Ah the stab in my skin when I read these lines. In ‘Notes on the unsilent woman’ Helen draws me in close, closer and then even closer to Hipparchia of Maroneia (c 350 – c 280 BC).

5. But I do have something to say. I want to say that she

lived. I want to say that she lived, and she spoke and she

was not silent.

Helen gathers 58 distinctive points in this poem to shatter the silence. Sometimes we arrive at a list of women who have been both audible and visible in history, but who may have equally been misheard, misread and dampened down. At other times the poet steps into view so we are aware of her writing presence as she records and edits and makes audible. In one breath the poet is philosopher: ‘Silence might not be speaking. It might be / listening. It can be hard to tell the difference.’ In another breath she apologies for taking so long to bring Hipparchia into the picture.

Elsewhere there is an ancient warning: ‘”If a woman speaks out of turn her teeth will be / smashed with a burnt brick.” Sumerian law, c. 2400 BC.’

A single line resonates with possibilities and the ‘we’ is a fertile gape/gap/breathing space: a collective of women, the poet and her friends, the women from the past, the poet and I: ‘There are things we didn’t think we could tell.’ Yes there are things we didn’t think we could tell but then, but then, we changed the pattern and the how was as important as the what.

Another single line again resonates with possibilities for me; it could be personal, it could equally be found poetry: ‘I would like to be able to say that it was patriarchy that stopped me talking on social media, but it wasn’t, not / directly.’

I read ‘Notes on the unsilent woman’ as a poem. I read this as an essay. I am tempted to carry on with my own set of bullet points as though Helen has issued an open invitation for the ‘we’ to speak. Me. You. They. She quotes Susan Sontag: ‘The most potent elements in a work of art are, often, its silences.’

The other poem I dearly love, ‘George Eliot: a life’, is also long form. Like the previous poem this appears as a sequence of numbered sections that are in turn numbered in smaller pieces. It is like I am reading a poem and then an essay and then a set of footnotes. An assemblage of fascinations. Biography as fascination allows room for anything to arrive, in which gaps are curious hooks, reflective breathing spaces and in which the personal is as compelling as the archives. Helen names her poem ‘A deconstructed biography’ and I am reminded of fine-dining plates that offer deconstructed classics. You get a platter of tastes that your tongue then collates on the tongue.

To taste ‘George Eliot: a life’ in pieces is to allow room for reading taste buds to pop and salivate and move. This is the kind of poem you linger over because the morsels are as piquant as the breathing spaces. It delivers a prismatic portrait of George Eliot but it also refreshes how we assemble a biography and how we shape a poem. Helen brings her acerbic wit into play.

10.7.1. But the fact is, and I don’t want to give you spoilers, that for such an

extraordinary woman she sure did create some disappointing female

characters. Even the heroines don’t strike out – they give up, they stop,

they enclose themselves in family, they stand behind, they cease, they die.

They found nothing.

10.7.2. Did she think she was too exceptional to be used as a model for her

characters? Did she think that while she was good enough to be involved

in intellectual life, and she could probably even be trusted to vote, the same

could not be said for her inferior sisters?

A number of smaller poems sit alongside the two longer ones including the moving ‘How to live though this’, a poem that reacts to an unstated ‘this’. ‘This’ could be anything but for me the poem reads like a morning mantra that you might whisper in the thick of tough times or alongside illness or the possibility of death.

‘How to live’ is a question equally open to interpretation as it ripples through the poems; and it makes poetry a significant part of the myriad answers. I haven’t read a book quite like this and I love that. The writing is lucid, uplifting, provocative, revealing, acidic, groundbreaking. The subject matter offers breadth and depth, illuminations, little anchors, liberations, shadows. I am all the better for having read this book. I just love it.

I slept my way into silence

through the afternoon, after days

of too many words and not enough words

to make the map she needs

to find her way from here

I wake, too late, with a headache

and she, in the garden wakes up shivering

from ‘Navigating by the stars’

Auckland University Press author page

Helen‘s ‘Mr Anderson, you heartbreaker you’

Helen on Standing Room Only