The Day

Cambrian Valley

The dog lies down in the shade of the table.

Knives lie down with pieces of lunch on them.

The mountains lie down across the valley

and the sunlight lies down across everything.

When we drive Neil says I love this:

the car and the music and the dog

and the sun and the spring and the lambs

and the light and the mountains and the sky.

The sky is so blue you can almost hear it skying.

Lynley Edmeades from Listening In, Otago University Press, 2019

Lynley Edmeades is a poet, essayist and scholar. Her debut collection As the Verb Tenses (2016) was longlisted for the Ockham New Zealand Book Award for Poetry and was a finalist in the UNESCO Bridges of Struga Best First Book of Poetry. She has a PhD in avant-garde poetics, and lives in Dunedin with her partner.

Otago University Press author page

Poetry Shelf review of Listening In

Listening In Lynley Edmeades, Otago University Press, 2019

Most of the time things slip

The seed on your plate slides

in the mess of leftover dressing

the hum of three street lights

making bright for no one

But every now and then

it feels as if things might hold

like here in this room

with its air and its airlight

from ‘Blue Planet Sky’

This is my summer holiday: reading gardening cooking walking on the wind-whipped beach. Trying to get better at sour dough. Most of all it is reading. Most of all it is reading novels. But some Aotearoa poetry books I dipped into in 2019 have been tugging at me, diverting me from the glorious satisfactions of fiction. I would hate to be a book-award judge this year as my shortlist of astonishing NZ poetry reads is Waikato-River long!

Here is another one is one to add to my list: Lynley Edmeades’s Listening In.

I adore this book. I adore the the extraordinary scope of writing.

The playful title evokes the reader bending into the frequencies of the poems but also underlines the attentiveness of the poet as she ‘listens in’ to her life, her preoccupations, the way words sing, misbehave, connect, disconnect, soothe, challenge. The linguistic play is breathtaking. You get different rhythms: from stammering staccato to sweet fluency, wayward full stops that introduce breathlessness, pause, discomfort, further pause. Verbs are signed posted (as is Lynley’s debut book As the Verb Tenses), as though each poem is a movement, as though each thing made visible is movement. A poem becomes a matter of being and doing in the now of the present tense.

The day unravels in the precarious throws of verb.

It’s everywhere we look: kitchen, bathroom, garden.

Even the floor waits in its doingness.

from ‘Things to Do With Verbs’

This is poetry as the flux of life where things are in place and out of place, where a great swell of language repeats and sidetracks and repeats again. You get to laugh and you get to feel. If we had all day, sitting together in a cafe or atop the dunes, I would tell you about the delights of each poem because there is such variation, such diverse impact as you read. ‘The Way’ is a knife-in-the-heart love poem and you have no idea the knife is coming and the love heat makes way for heartbreak. ‘Where Would You Like to Sit’ is an anxiety poem where questions pose as statements in a therapist’s chair.

You have to read the poems to see how they gather inside you. How the language gathers inside. How you can’t stop feeling the poems: the wit, the music, the originality.

Lynley takes three politicians as poem starting points. ‘Speetch’ is a transliteration of ex Prime Minister John Key’s valedictory speech in parliament. ‘Again America Great Make’ quantifies Donald Trump’s inauguration speech. ‘Ask a Woman’ juxtaposes Margaret Thatcher quotes that Lynley found online. All three poems are quite disconcerting!

(..) But long

before Wall Shtreet my political views hid been shaped by my Aushtrian Jewish

mutha Ruth, who single handedly raised me and my sisstas in now the infimiss

state house at nineteen Hollyfird Av Christchurch. My mutha wazza no nonsense

womin who refused to take no in answer. She wuddun accept fayure.

from ‘Speetch’

On other occasions a single word (stone, because) prompts a poem like an ode to a word that shadows an ode to experience. ‘Poem (Frank O’Hara Has Collapsed)’ spins on the word ‘collapse’ like a free wheeling stream of consciousness unsettling whirlpool. I adore these poems. ‘Islands of Stone’ leads from physical stones to language play. A quote from Viktor Shklovsky heads the poem and it is how I feel about the book: ‘Art exists that one may recover the sensation of life, it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony.’

Stone-sober stone

Getting-stoned stone

Stepping-stone stone

Sticks-and-stones stone

Leave-no-stone-unturned stone

Blood-from-a-stone stone

Two-birds-with-one-stone-stone

A-stone’s-throw stone

Then there are the poems that glow. That fill you with poetry warmth. I am thinking of ‘Constellations’, a in which Chloe tells us ‘we draw stars/ around the adjectives/ to identify them’. She is writing a story about friends and lunchtime at school and whether friends are kind or nice.

It has little shadows

of very and kinda

that reach out

towards the stars.

Perhaps another way to view Listening In is as translation. A small poem ‘The Order of Things’ makes multiple appearances (it originally appeared in As the Verb Tenses) as half-translations and iterations. I am thinking each book we write is enmeshed in the books that we wrote before, and the books we write foreshadow the books to come. Lynley is translating the world (life) with an exuberance of words, out-of-step syntax (a nod to Gertrude Stein), repeating motifs, word chords, word cunning and delicious humour. She tests what a poem can do by testing what words can do and the effect is awe-inspiring. It makes me want to write. It makes me want to put the book in your hand. Because. Because. Because. Life is here out in the open and hiding in the crevices. Because. Because. Because. Her words open up like little explosions inside you and you know poems can do anything. I have barely touched upon what this poetry does. I love love love this book.

Otago University Press author page

Lynley Edmeades is a poet, essayist and scholar. Her debut collection As the Verb Tenses (2016) was longlisted for the Ockham New Zealand Book Award for Poetry and was a finalist in the UNESCO Bridges of Struga Best First Book of Poetry. She has a PhD in avant-garde poetics, and lives in Dunedin with her partner.

Global

Search for counter-attack

Replace with hold

Search for attack

Replace with attach

Search for murdered

Replace with heard

Search for killed

Replace with serenaded

Search for ambushed

Replace with invited

Search for missile launchers

Replace with, oh, red silk fans

Search for front line

Replace with lamp-lit threshold

Search for grenades

Replace with iris bulbs

Search for smart bombs

Replace with crayoned paper folded into lilies, swans

Search for generals

Replace with farmers, orchardists, gardeners, mechanics, doctors, veterinarians, school-teachers, artists, painters, housekeepers, marine biologists, zoologists, nurses, musicians

Search for combatants

Replace with counsellors, conductors, bus drivers, ecologists, train drivers, sailors, fire-fighters, ambulance drivers, historians, solar engineers, designers, seamstresses, artesian well-drillers, builders

Search for profits

Replace with prophets

Save as

New World.doc

Emma Neale

from Tender Machines (Dunedin: OUP, 2015)

Emma Neale is the author of 6 novels and 6 collections of poetry. She is the current editor of Landfall.

Otago University page

Otago University Press media release: Unpredictable powers of non-human world inspire winning collection

Lyttelton poet Philip Armstrong has won the 2019 Kathleen Grattan Award with his poetry manuscript ‘Sinking Lessons’.

‘Sinking Lessons’ was described by judge Jenny Bornholdt as an ‘accomplished, engaging collection of poems that displays literary skill and a sharp intelligence at work.’

‘There’s great affection for life of all kinds – human and the natural world – coupled with an awareness of the fragility of existence,’ she says.

Philip Armstrong says the poems in his collection are shaped by two main themes: the sea and the agency of the non-human world in general.

‘I grew up in a house beside the Hauraki Gulf, and for the last two decades I’ve lived within sight of Lyttelton Harbour, and the sights and sounds and smells of salt water make their way into my poetry whether I intend it or not’.

‘The other theme linking these poems is my attempt to recognise the active, mobile, lively, unpredictable capacities of the non-human world, from animals and plants through to waste matter and refuse, through to land forms and weather patterns.’

The biennial poetry award from Landfall and the Kathleen Grattan Trust is for an original collection of poems, or one long poem, by a New Zealand or Pacific permanent resident or citizen. Landfall is published by Otago University Press.

Philip Armstrong receives a $10,000 prize and a year’s subscription to Landfall, and Otago University Press will publish his collection in 2020.

For more information about Kathleen Grattan and the history of the award

About Philip Armstrong

Philip Armstrong works at the University of Canterbury, teaching literature (especially Shakespeare), human–animal studies, and creative writing (including poetry).

He has written a number of scholarly books (two on Shakespeare, and two on animals in literature) as well as a book for a general audience (about sheep in history and culture). In 2011 he won the Landfall Essay Prize for a piece about the Canterbury earthquakes, entitled ‘On Tenuous Ground’. ‘Sinking Lessons’ is his first collection of poetry.

Nodding is Soft

I can only tell you. What I saw.

And all I can. Say is that you.

Wouldn’t have wanted. To see it

yourself no. Sir it was not.

For public. Consumption it was

very hard and very. Bad probably

the hardest and. Baddest thing

to see but yes. I saw. It I saw

it hard and it was. Bad but even

when I. Saw it I didn’t say. Wow

that is the hardest. Thing I’ve ever

seen I just. Said when. Are we

leaving and you. Said well we

can leave when. You’ve finished

looking at the. Thing you’re looking

at. And so I turned. Away but

already I. Knew it was. Not

worth telling you. About this

most hardest and. Baddest thing

it is not. Soft not like your. Nodding

is soft. But why are. You nodding

don’t you know. That this is. The

hardest and baddest. Thing. No you.

Don’t understand it is. The worst.

I can only. Tell you what.

Lynley Edmeades, Listening In, Otago University Press, 2019

Lynley Edmeades completed an MA at the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry at Queen’s University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, in 2012. Her first collection of poetry, As the Verb Tenses (Otago University Press, 2016) was longlisted for the Ockham NZ Book Awards for Poetry, and shortlisted for the UNESCO Bridges of Struga Best First Book Award. She has a PhD in avant-garde poetics and teaches literature and creative writing at the University of Otago.

Otago University Press page

Lynley in conversation with Lynn Freeman (it’s terrific) Standing Room Only

Diana Bridge reads ‘A pounamu paperweight’ from Two or more islands (Otago University Press, 2019)

Diana Bridge has a PhD in Chinese classical poetry from the Australian National University, received the 2015 Sarah Broom Poetry Prize and has published numerous collections of poetry. She received the Lauris Edmond Memorial Award in 2010 for her outstanding contribution to New Zealand poetry. Elizabeth Smither writes: Diana’s ‘range is both local and international, delicate and down to earth, and at the same time, probing and intensely rewarding.’ Vona Groarke wrote in her judge’s report for the Sarah broom Poetry Award that Diana’s work ‘is possibly amongst the best being written anywhere right now– for the arresting composure of the poems, for their reach and depth, for their carefully wrought thought and language, for the beauty of their phrasing, for how they are both intellectually astute and also sensual and accessible, for the way they catch you up short and make you wonder.’

Cold Hub Press published In the Supplementary Garden: New and Selected Poems with an introduction by Janet Hughes in 2010. Two or more islands came out in June of this year from Otago University Press. About eighteen months before, she completed, with Peter Harris, a collaborative translation of a selection of Chinese classical poems. As well, last year she was interviewed, as one of eleven New Zealanders who have worked on aspects of China, for a project called ‘The China Knowledge Project’. The collected interviews are to be published.

Harry Rickett reviews Two or more islands on RNZ National

Poetry Shelf interviews Diana Bridge

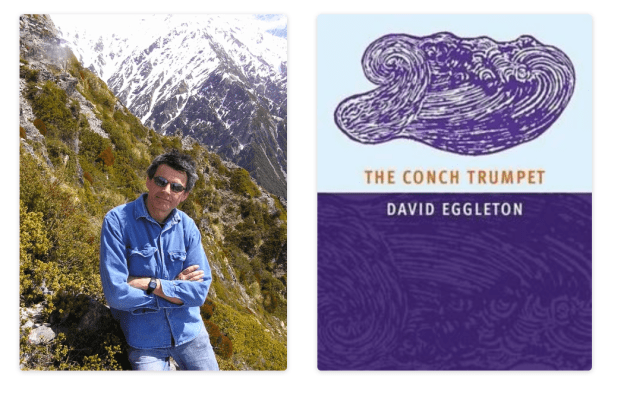

To celebrate the announcement of our new Poet Laureate, David Eggleton, I have scoured the Poetry Shelf archives and rediscovered this interview. I welcome David as Poet Laureate: he is a charismatic poet and performer, and a longtime ambassador for poetry in Aotearoa. It is good to have a Dunedin-based Laureate.

I posted this interview in 2015 on the publication of The Conch Shell (OUP). Since then The Conch Trumpet won the Poetry Award at the 2016 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. He has held the Fulbright-Creative New Zealand Pacific Writer’s Residency at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, received the Prime Minister’s Award for Poetry (2016) and published edgeland and other poems (OUP, 2018).

An interview with David Egggleton

Photo credit: F. J. Neuman

Photo credit: F. J. Neuman

David Eggleton is a poet, reviewer and non fiction writer. His books include: Here on Earth: the Landscape in New Zealand Literature, (Craig Potton Publishing, 1999); Seasons: Four Essays on the New Zealand Year, (Craig Potton Publishing, 2001); Ready to Fly: the Story of New Zealand Rock Music, (Craig Potton Publishing, 2003); Into the Light: a History of New Zealand Photography, (Craig Potton Publishing, 2006); and Towards Aotearoa: A Short History of Twentieth Century New Zealand Art (Reed/Raupo, 2008). His poetry collections include: Rhyming Planet, (Steele Roberts, 2001); Fast Talker, (Auckland University Press, 2006); Time of the Icebergs, (Otago University Press, 2010); and The Conch Trumpet (Otago University Press, 2015). He is the current Editor of Landfall and of Landfall Review Online (now Emma Neale). He lives in Dunedin.

To celebrate the arrival of his new poetry collection, The Conch Shell, David kindly agreed to answer some questions for Poetry Shelf.

‘Stone clacks on stone

so creek lizards slither,

runnels slip through claws,

each cloud’s a silver feather.’

from ‘Raukura’ in The Conch Trumpet

Did your childhood shape you as a poet? What did you like to read? Did you write as a child? What else did you like to do?

I had very little to do with books as a child, apart from prolonged weekly exposure to the King James Bible. However, it was a rich, sensual and even privileged environment, with wide exposure to a variety of cultures and a strong sense of the carnivalesque about everyday life. My father at that time was a soldier ant, when the last Pacific colonies were gaining independence, and then there were my mother’s ancestral voices and her extended family. This idyll was abruptly terminated when our family relocated permanently from Fiji to New Zealand. It was a bit like the post-Edenic Fall, though gradually I became aware of a different kind of richness, including eventually the world of the library.

In early adolescence my options veered between seminary school and reform school, though neither eventuated. I began to understand that truth, social truth at least, is not absolute but institutional and class-bound, and you need a ticket to get in — but if you are a poet you can construct your own truth. ‘I am the shadows my words cast’, as Octavio Paz wrote.

My early literary influences, besides the Bible, included Phantom comics, church music, gospel choirs and listening to pop music on the radio: an auditory riot. The Bible contained fascinating and troubling verses: ‘Eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe…’

Meantime, living in South Auckland there were not the quiescent, somnolent afternoons of lawn tennis such as you might have found in the leafy avenues of the inner suburbs, but rather the lingering smell of tanneries and abattoirs — offal being boiled down at the freezing works, corned beef being cooked for shipment to the Islands. This became partly associated in my mind with the lives of saints and martyrs I had already spent time reading about: believers being boiled in oil by non-believers, and so forth. There was also much bellowing in the streets and the roar of motorcycles.

When you started writing poems as a young adult, were there any poets in particular that you were drawn to (poems/poets as surrogate mentors)?

I got interested in writing at high school, my first published efforts appearing in the Aorere College literary magazine. Around the same time, I was discovering Dylan Thomas, Gerard Manley Hopkins, T. S. Eliot, Gunter Grass — some of these were on the school curriculum.

Then I got immersed in the American Beats and their ‘action writing’: Go! Howl! On the Road! I heeded the call; I dropped out of school and tried to get a job on a cargo ship. I wasn’t taken on, so I got a job in a South Auckland carpet warehouse instead. Kerouac’s road novels were a word-spattered canvas wide as America and seemed related to the Ab-Ex canvases of the artist Jackson Pollock, whose paintings I also got interested in.

Energised, I sought to emulate the yackety-yak spoken word rhythms of Jack Kerouac, the biting wisecracks of William Burroughs and the vatic yawp of Allen Ginsberg in my own screeds of verse. And then there was the one-man typographical liberation front of e.e. cummings: ‘anyone lived in a pretty how town and down they forgot as up they grew…’

I was pretty much unaware of New Zealand writing, apart from the plummy-voiced Bruce Mason, who had visited our school out in the sticks with his one-man theatrical show.

I remember when you were awarded London Time Out’s Street Entertainer of the Year in 1985. From that time you have gained a solid reputation as a performance poet. Do you still see yourself as a performance poet? Did the award alter the path of poet for you at all?

Well, 1985 was New Zealand’s special moment in the sun, with David Lange roaming the globe as a kind of No Nukes! ambassador, and Keri Hulme winning the Booker Prize. There was a big travelling Maori art exhibition, plus the Rainbow Warrior bombing, the Flying Nun catalogue. All that kind of created a climate where things New Zild were of interest in the UK, and I was able to get on and stay on the cabaret circuit at the time.

Performance for me became a poetry vehicle and there was a national consciousness locally it tapped into: grass roots, flax roots, ground up, underground, public assemblies to hear, watch, attend to, what poets and other performers were saying — and maybe have all this on at a variety night down at the community hall.

Things have changed, become more sophisticated, more ironic, more knowing. Perhaps there is less of a communal thing now and more of a tightly-organised, clearly-defined niche market, maybe even a gentrification of poetry scenes — where the confessional genre and the misery memoir have top billing, everyone competing to prove that they have the tiniest violin in the world and they know how to play it. I enjoyed, and still enjoy, the Dadaist nature of the wilder poetry performance. The novelist Henry James said about a poetry reading by Robert Browning that, if the audience didn’t understand his poems he seemed to understand them even less: ‘He reads them as if he hated them and would like to bite them to pieces.’ That sounds like my kind of event.

I love the way your poems absorb and replay the world in a dazzling eruption of detail, hallucinogenic at times. It is like standing in the street or bush just after it has rained. Luminous. Invigorating. Yet as much as each poem is an aural feast, there is an engagement with the world on multiple levels. What are key things for you when you write a poem?

Incantation, cadence, rhythm, pacing, matter more to me than formal metre stress and scansion. I like overgrown gardens and rainforest: that which is lush. I like absurdity and contradiction as closer to real experience rendered more accurately. In poetry, arguably, lexical meaning is less important than rhythm and emotionally-charged sound, which have their own echo-chamber allusiveness.

All that said, I also like psychedelic dream-fever imagery, and teasing evocations of mythical ancestors and invented traditions: invented traditions which engage with canonical poems, the poems which begin, as Yeats put it, in the foul rag and bone shop of the heart, but then become marble, monumental.

Poems are generated in many different ways, of course. Sometimes a poem might begin as a psychotherapeutic notion, as automatic writing, where as long as you keep writing you eventually find the solution to whatever it is that ails you, psychosomatically or existentially. Other poems may be less fluent; instead they are painstakingly assembled, built up like a movie in an editing suite from many separate images in order to create a mood, an atmosphere, a climate.

What one does not want is what Yeats (again!) described as ‘the stale odour of spilt poetry’: we want the fresh bouquet of wild flowers — or of hothouse blooms transfigured. Poetry remains in the service of the subversive. That’s its power. The magical thinking of the ancient gods has been replaced by a future of junk science, which explains that emotions are only neuropeptides attaching to receptors and stimulating an electrical charge on neurons. Easy-peasy. How might a poet extract a poem from this revised reality? That’s the challenge.

Do you see yourself as a political poet? Overtly so or in more subtle ways?

Poetry is politics by other means; anthologies prove this. But I think what you are getting at is the idea of poets on the barricades leading the revolution. OK, the revolution may not be televised, as Gil Scott-Heron prophesied in his debut album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox back in the 1970s, but these days it’s corporatised and monetised. As Arundhati Roy has pointed out, in the era of the free market, ‘free speech’ has become a valuable commodity, too valuable to be wasted on the underclass. Poetry must find ways to remain anarchic, not for sale. As the Zen poem has it: ‘Sitting quietly doing nothing/ Spring comes and the grass grows by itself.’

My favourite poets include the Nightingale and the Skylark: Keats and Shelley — not yet Pixar characters — and Shelley undoubtedly was a revolutionary bard who believed that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. Likewise, William Blake was a revolutionary, but he wasn’t arrested and beheaded because they considered him mad. Nowadays we consider him a visionary.

I am inspired by the poetry of witness: that of Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, Georg Trakl, John Clare, Pablo Neruda. These poets spoke truth to power and sometimes paid with their lives.

New Zealand is a relatively lucky country, but it also means, I think, that we have an obligation to speak out against injustice, though not necessarily through simple polemics. Poetry, said Auden, makes nothing happen — well, many poets would disagree. Poetry can help generate social earthquakes — or be part of them in subtle ways. Globalisation is all subtle interconnections.

One poem in my new book was inspired by the sight of a superyacht belonging to a Russian oligarch in Auckland’s Viaduct Basin, an impressive white vessel designed by Philippe Starck. I stayed on the wharf for a while, and revisited, watching the comings and goings on this superyacht, and then researched the background — or rather added to what I already knew. That’s the starting point for a poem, which is not so much about Putin’s Russia as about the approved neo-liberal narratives of today and the warped truths which seem to accompany unbridled power. Yet nothing is spelt out — the reader must surmise, or suspect.

Pablo Neruda said that a poem is a net, and in a net it’s not just the strings that count but also the air, or the ocean, that escapes through them. To which I might add about my poem that while ‘knowledge’ is steady and cumulative and a satisfying form of story-telling, ‘information’ is random and miscellaneous and frustrating. My poetry sometime plays around with these twinned perceptions. For, as Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote: ‘the poet knows he speaks adequately only when he speaks somewhat wildly, not with the intellect alone, but with the intellect inebriated by nectar.’

The fact is that the black rain of tragic images is unending. The poet must put out his bucket and collect enough, and then endeavour to make sense of them; find a way to transform the surplus into poetry. Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry said Auden of Yeats, rather contradicting his other statement that poetry makes nothing happen. The ambitious poet is a voyant, a seer still, despite the scoffers, disdainful of rolling up their sleeves, spitting on their hands and going to work. Delmore Schwarz was right: in dreams begin responsibilities.

From the frantic antics of the nuclear meltdown to the shirtfronting of the financial meltdown, there’s plenty happening politically that cries out for poems. Then, too, as New Zealanders we need to constantly catechise our past in poetry so as to attest to our grasp of identity. Because this collective past, the stuff of song, ballad and pontificating political speech, is only approximately remembered, or else only partly told. Different people will tell, for example, the story of the Treaty of Waitangi in skewed fashion, laying emphasis on different details, and carry this away as poetic myth. The poet of conscience searches out social stigmas, personal stigmas, linguistic stigmas — the difficult subjects — and finds new ways to address them.

Do you think we have a history of thinking and writing about the process of poetry? Any examples that sparked you? Have you done this?

Yes, of course we have a tradition of thinking about what poetry is. Manifestos, prefaces, books and essays by Allen Curnow, A.R.D. Fairburn, Alan Brunton, Riemke Ensing, Kendrick Smithyman, Ian Wedde, Bill Manhire, Murray Edmond, C.K. Stead and Robert Sullivan are amongst those I value most. A writer is a descendent of other writers. I’ve written a lot in response to reading other poets; that is, to specific instances, but not manifestos or generalising, barrow-pushing commentaries.

New Zealand has its own quirky bicultural literary history. There’s also a strong puritanical tradition, nowhere so pronounced, I think, as in the repressed verses of Charles Brasch. He reminds me of what Anthony Burgess once said about himself: that he was so much of a puritan that he couldn’t describe a kiss without blushing. That said, there’s a value in circumspection, in euphemism, in artful disguise: telling by other means.

Actually, I think that all the theorising stacks up to mere post-rationalisation, to temperaments attempting to influence posterity, whereas, as John Steinbeck put it: ‘Time is the only critic without ambition’. Instead, I would argue that we learn most by example — the example of careful noticers, and for me one of the influential is Katherine Mansfield, still one of our best, perhaps our best, echo-locators: ‘All that day the heat was terrible. The wind blew close to the ground, it rooted among the tussock grass, slithered along the road, so that the white pumice dust swirled in our faces.’ So much menace, so close to home.

What poets have mattered to you over the past year? Some may have mattered as a reader and others may have been crucial in your development as a writer.

It would take a book to answer this question adequately. I’ve read the work of around 1000 poets over the past year, and all of them mattered at the time of reading. To read a poem properly is to engage with it, alertly. Listing names and poems that grabbed me would be counter-productive, because each would require an explanation of the encounter: what the sense and what the sensibility? Deconstruction at warp speed cannot happen in this format.

What New Zealand poets are you drawn to now?

Currently my favourite New Zealand poet, in the terms of the poet I am thinking most about, is Robin Hyde, followed by Ursula Bethell and A.R.D. Fairburn. So many clues, or soundings, to where we are now lie in the inter-war years. Other than that, I pretty much read everybody.

Do you think your writing has changed over time?

My own feelings about this are, necessarily, extremely subjective, but I would advance a cautious perhaps. According to Heraclitus, everything flows and all movement is history. William Blake said that without contraries there is no progression. In short: change is the only constant in life; one writes not as one was, but as one is.

Certainly the cultural climate has changed, and my corporeal self has changed. The typical New Zealand afternoon of the recent past had all the excitement of a damp tea towel and all the urgency of a dripping tea urn, with somewhere the smell of scones burning. Somehow this no longer seems applicable. Along with Denis Glover though, I do not dream of Sussex downs or quaint old English towns — I think of what may yet be seen in Johnsonville and Geraldine.

You write in a variety of genres (poetry, short fiction, non-fiction, critical writing). Do they seep into each other? Does one have a particular grip on you as a writer?

All of my writing is really just personal essays by other means — that is, if you consider the personal essay a form of self-correction, a form of self-contestation, an interior monologue conducted in solitude in preparation for being presented in public. Otherwise, the prescriptions of each genre apply, distinctly.

However, in my view, literature is or should be a site of struggle, no matter what the genre. Each mode is always inherently in a state of primal conflict about purpose and meaning. Otherwise it is moribund, mere cliché-recycling.

There are elements of hybridity, the mongrel, in my writing. The mixed bag, the medley, the odd job lot, the tall order; that’s what I’ve ended up doing. To pluck out just one continuity: I have an overarching interest in the iconoclastic — how might we tear all these false idols down. And aren’t they all false anyway? So there you go; we’re always casting about for the new, the next, supreme fiction.

The detail you collect makes place so vital — and that place emerging is particular, local, recognisable. For me, the poems transcend poetic exercise or form as they establish contact with what it might or might not mean to be human. These poems tick with humanity. Is a sense of home an important factor as you write? Or connections with humanity?

The Rumanian philosopher E.M. Cioran wrote that you don’t inhabit a country, you inhabit a language, and as Caribbean poet Derek Walcott pointed out, when you inhabit a language you enter into a relationship with its imperial width. A language is not a place of contemplative retreat or escape; it’s a site of struggle. Struggle for control, or, to use Kendrick Smithyman’s formulation, ‘a way of saying’. So, it starts with the language, which works on homegrown imagery. As Ian Wedde once neatly put it, my poetry is preoccupied with ‘growth into location’. Not just that, but this regionalism reflects the society’s obsession with where it is: Anne French’s one big waka, Robert Sullivan’s hundred small waka.

This, in a way, is ‘small country syndrome’ and Dylan Thomas wrote something eloquently pertinent to this sense of us against the world in a letter to his wife: ‘the world is unbalanced unless, in the very centre of it, we little mutts stand together all the time in a hairy, golden, more-or-less unintelligible haze of daftness.’

By not living in exile, by living here, the whole past stays in the pulsating present. Wherever I turn, I see reminders of things past, of ghost trails, phantoms. As I write this, autumn rains are bashing at the windows in silver-grey lights as the furthermost fringe of Cyclone Pam brushes past. That’s what being here means to me. That and folk memories: cow cockies used to tighten Number 8 wire with a strainer until it literally sang when it was flicked. Now whole rugby stadiums hum that same tune.

This is a land of miraculous icons, a poet’s task is to discover and celebrate them before the local version of the Taliban, often in the form of a property developer, moves in and breaks them up.

What irks you in poetry?

I’m not sure that any poem irks me. Rather, the challenge is: what is the poet doing? Has it been achieved? Sometimes poems feel hollow, or are expressed in sentiments that have a breathy earnestness, yet you know that they know that you know they haven’t got there and earned it. Kate Clanchy wrote recently in the UK Poetry Review about a new collection of poems by Ruth Padel that some poems took your assent, your acquiescence, for granted because these were poems about ‘the Holocaust’. In fact, poems should take nothing for granted but must make their case through genuinely felt details, line by scrupulous line, even when about a supposedly sacrosanct subject. Even when a poem’s a failure, it remains interesting, through falling short.

What delights you?

The achievement, the mastery of the thing. Or else it falls away sharply to hit the ground with a thump. That said, value judgements are complex things, governed by notions of taste, knowledge of context, histories of contestation. A poem that appears to fly high to you — an ode to the west wind, a hymn at heaven’s gate — may not seem that way to another reader or listener.

Name three NZ poetry books that you have loved.

Just quickly. Runes (1977), by James K. Baxter. He was, at one time, both my spice paladin and my herb goblin. No Ordinary Sun (1977), by Hone Tuwhare. He could use his diaphragm like a sounding board, a sea chest. Inside Us the Dead (1976), by Albert Wendt. I was delighted by his witty reportage in the immediate post-colonial moment in the newly emergent Pasifika.

I love the title of your new collection (The Conch Shell). The blurb suggests that this collection ‘calls to the scattered tribes of contemporary New Zealand.’ What tribes do you belong to? What literary tribes? How does the word ‘contemporary’ modify things?

Yes, I’m blowing my own (conch) trumpet at sunrise. That title refers to tide-lines of life, to surf-like sounds, to gathering good vibrations, to gods of the sea who, clarion-like, lull the waves, and to the summer of shakes, the year of quakes. And so on, to the final burnout of the run-ragged consumer. The rest is the tribal outcast, and everything you cannot pin down, or ascribe a bar code to.

In fact, the word ‘tribe’ is fraught. I think James K. Baxter brought it into the literary realm. My own tribal background is distinctly heterogeneous rather than Fonterra-homogenous, but if I look around at my contemporaries, poets and otherwise, I see most of them making it up as they go along. A poem tests a proposition; it doesn’t always prove it.

These new poems offer shifting tones, preoccupations, rhythms. What discoveries did you make about poetry as you wrote? The world? Interior or external?

My poems like to dwell on the silver wake of a container ship, or the wet sand beneath the upturned hull of a dinghy, or the half-seen, the overheard. Poets re-arrange, but they have duties of care. X.J. Kennedy has pointed out that: ‘The world is full of poets with languid wrenches who don’t bother to take the last six turns on their bolts.’

It’s been five years since my last poetry collection Time of the Icebergs appeared, and one reason my collections have been regularly spaced that far apart is the need for more elbow-grease and line-tightening to get the burnish just so.

The poet’s mind, like anyone else’s is made up of reptilian substrate, limbic empathy and neo-cortical rationality. These shape your reveries and hopefully together lift them out of banality. Our ideas are dreams, styles, superstitions. We rationalise our temperaments, draw curtains over our windows, but poems carry an anarchic charge that reveals the force that through the green fuse drives the flower.

A poet is in the business of the unsayable being said, showing you fear in a handful of dust. A poet is amanuensis to the subconscious ceaselessly murmuring, and indeed to the planetary hum, the gravitational pull of the earth, the wobble of placental jellyfish in the womb — anything alive, mindless and gooey.

Is there a single poem or two in the collection that particularly resonates with you?

Every poem resonates on its own wavelength, but I found constructing an immediate elegiac response to my father’s death one of the most turbulent. A bit like getting to grips with a storm, with a howling wind that has shape and substance.

Returning to the notion of detail, I see the accumulation of things in your poems as an overlay of highways to elsewhere whether heart, issues, ideas, fancy, memory. Yet the things also pulsate as things in their own right. What draws you to ‘the thisness of things’ (the blurb)?

Things accumulate in my poems in almost haptic fashion, wrestled there like sculptural ingredients. They accumulate, as in the random haphazard assemblages of the Dadaist Kurt Schwitters, built out of found objects in the streets. Yes, I want to acknowledge the ‘thisness’ of things, but not in the sense of ‘property’. Rather, in the sense of: he who kisses the joy as it flies, lives in eternity’s sunrise.

Is doubt a key part of the writing process along with an elusive horizon of where you are satisfied with a poem?

I can’t get no satisfaction. Actually, poets need to be their own sophisticated antagonists. After all, why write? There’s always a struggle going on between self-revelation and self-concealment. Poetry is a kind of verbal tic; it runs in parallel with consciousness. To be conscious and verbal are vital signs, as Les Murray has pointed out. Then comes the self-questioning: are these fifty poems, fifty varieties of same-same? Is this what the thunder truly said? Is this poem really language dancing, and is it top of the poppermost — that is, is it the best you can do? All this nervous self-doubt surrounds the birth of a successful poem, I think.

The constant mantra to be a better writer is to write, write, write and read read read. You also need to live! What activities enrich your writing life?

Much time is taken up by arts-related stuff: gallery-going, movie-going, theatre-going, concert-going, poetry recitals, beer-sampling, weekend dabbling in arty-crafty matters. And then also I like to get out and about in the landscape: tramping through national parks, exploring West Coast walkways, cycling around Waiheke Island, or across the Mackenzie Country, climbing the lower slopes of the Southern Alps, and on and on. Typical Kiwi pastimes that keep one modestly prepared for the long sedentary hours ahead.

Some poets argue that there are no rules in poetry and all rules are to be broken. Do you agree? Do you have cardinal rules?

Poets are actually not their own creatures. They imitate their forebears. In her diaries, Susan Sontag wrote: ‘Poetry must be exact, intense, concrete, significant, honed, complex.’ She wrote this sentence as a high Modernist priestess when that kind of poetic faith was at its apogee, nevertheless I’d go along with that as an aspirational motto. Yeats again: ‘How but in custom and ceremony are beauty and innocence born?’

There are always rules. A poem — even one generated by a computer — follows rules. But these rules vary poem to poem, and the end result is not about the rules but about organic coherence and meaningfulness.

Here’s another Katherine Mansfield sentence (she’s endlessly quotable), and one William Burroughs would surely have applauded. The reasons why she wrote this don’t matter. What matters is the imagery and the pacing, the rhythm: ‘I took the revolver into the garden today and practised with it, how to load and unload and fire.’ A great New Zealand sentence.

Do you find social media an entertaining and useful tool or white noise?

Hyperreal, hyperventilating, hyper-opinionated, it’s the new centre of gravity — or else a black hole that will swallow the sun, and take all the time you have. I try to minimise my involvement. As for poetry, the internet works well as an events noticeboard, but actual poems feel anaemic on it, drained and destabilised, apt to float away into cyberspace, never to be seen again.

Finally if you were to be trapped for hours (in a waiting room, on a mountain, inside on a rainy day) what poetry book would you read?

Well, today, a big compendium that includes Auden’s ‘ 1 September 1939’, Owen’s ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ and ‘The Road to Mandalay’, ‘The Waste Land’, Christina Rossetti, and bits of Don Juan, the Sonnets of Shakespeare… ‘But I think my head is burning and in a way I’m yearning to be done with all this measuring of proof…’

Otago University Press page

New Zealand Book Council author page

New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre page

m y h i g h l i g h t s

I have had endless opportunities to transform the days and nights of 2018 with poetry musings. What good is poetry? Why write it? Why read it? Because it energises. Because it connects with the world on the other side of these hills and bush views. Because it gives me goose bumps and it makes me feel and think things.

I am fascinated by the things that stick – the readings I replay in my head – the books I finish and then read again within a week – the breathtaking poem I can’t let go. So much more than I write of here!

I have also invited some of the poets I mention to share their highlights.

2018: my year of poetry highlights

I kicked started an audio spot on my blog with Chris Tse reading a poem and it meant fans all round the country could hear how good he is. Like wow! Will keep this feature going in 2019.

Wellington Readers and Writers week was a definite highlight – and, amidst all the local and international stars, my standout session featured a bunch of Starling poets. The breathtaking performances of Tayi Tibble and essa may ranapiri made me jump off my seat like a fan girl. I got to post esssa’s poem on the blog.

To get to do an email conversation with Tayi after reading Poūkahangatus (VUP) – her stunning debut collection – was an absolute treat. I recently reread our interview and was again invigorated by her poetry engagements, the way she brings her whanau close, her poetry confidence, her fragilities, her song. I love love love her poetry.

My second standout event was the launch of tātai whetū edited by Maraea Rakuraku and Vana Manasiadis and published by Seraph Press. Lots of the women read with their translators. The room overflowed with warmth, aroha and poetry.

At the same festival I got to MC Selina Tusitala Marsh and friends at the National Library and witness her poetry charisma. Our Poet Laureate electrifies a room with poems (and countless other venues!), and I am in awe of the way she sparks poetry in so many people in so many places.

I also went to my double poetry launch of the year. Chris Tse’s He’s So MASC (AUP) – the book moved and delighted me to bits and I was inspired to do an email conversation with him for Poetry Shelf. He was so genius in his response. Anna Jackson’s Pasture and Flock: New and Selected Poems (AUP) delivers the quirkiest, unexpected, physical, cerebral poetry around. The book inspired another email conversation for the blog.

Tusiata Avia exploded my heart at her event with her cousin Victor Rodger; she read her challenging Unity and astonishing epileptic poems. Such contagious strength amidst such fragility my nerve endings were hot-wired (can that be done?). In a session I chaired on capital cities and poets, Bill Manhire read and spoke with such grace and wit the subject lit up. Capital city connections were made.

When Sam Duckor-Jones’s debut collection People from the Pit Stand Up (VUP) arrived, both the title and cover took me to the couch to start reading until I finished. All else was put on hold. I adore this book with its mystery and revelations, its lyricism and sinew; and doing a snail-paced email conversation was an utter pleasure.

I have long been a fan of Sue Wootton’s poetry with its sumptuous treats for the ear. So I was delighted to see The Yield (OUP) shortlisted for the 2018 NZ Book Awards. This is a book that sticks. I was equally delighted to see Elizabeth Smither win with her Night Horses (AUP) because her collection features poems I just can’t get out of my head. I carry her voice with me, having heard her read the poems at a Circle of Laureates event. I also loved Hannah Mettner’s Fully Clothed and So Forgetful (VUP), a debut that won best first Book. How this books sings with freshness and daring and originality.

I did a ‘Jane Arthur has won the Sarah Broom Poetry Award and Eileen Meyers picked her’ dance in my kitchen and then did an anxious flop when I found Eileen couldn’t make the festival. But listening to Jane read before I announced the winner I felt she had lifted me off the ground her poems were so good. I was on stage and people were watching.

Alison Glenny won the Kathleen Grattan Award and Otago University Press published The Farewell Tourist, her winning collection. We had a terrific email conversation. This book has taken up permanent residence in my head because I can’t stop thinking about the silent patches, the mystery, the musicality, the luminous lines, the Antarctica, the people, the losses, the love. And the way writing poetry can still be both fresh and vital. How can poetry be so good?!

I went to the HoopLA book launch at the Women’s Bookshop and got to hear three tastes from three fabulous new collections: Jo Thorpe’s This Thin Now, Elizabeth Welsh’s Over There a Mountain and Reihana Robinson’s Her limitless Her. Before they began, I started reading Reihana’s book and the mother poems at the start fizzed in my heart. I guess it’s a combination of how a good a poem is and what you are feeling on the day and what you experienced at some point in the past. Utter magic. Have now read all three and I adore them.

At Going West I got to chair Helen Heath, Chris Tse and Anna Jackson (oh like a dream team) for the Wellington and poetry session. I had the anxiety flowing (on linking city and poet again) but forgot all that as I became entranced by their poems and responses. Such generosity in sharing themselves in public – it not only opened up poetry writing but also the complicated knottiness of being human. Might sound corny but there you go. Felt special.

Helen Heath’s new collection Are Friends Eectric? (VUP) was another book that blew me apart with its angles and smoothness and provocations. We conversed earlier this year by email.

A new poetry book by former Poet Laureate Cilla McQueen is always an occasion to celebrate. Otago University Press have released Poeta: Selected and new poems this year. It is a beautiful edition curated with love and shows off the joys of Cilla’s poetry perfectly.

Two anthologies to treasure: because I love short poems Jenny Bornholdt’s gorgeous anthology Short Poems of New Zealand. And Steve Braunias’s The Friday Poem because he showcases an eclectic range of local of poets like no other anthology I know. I will miss him making his picks on Fridays (good news though Ashleigh Young is taking over that role).

Highlights from some poets

Sam Duckor-Jones

I spent six weeks reading & writing poems with the students of Eketahuna School. They were divided on the merits of James Brown’s Come On Lance. It sparked a number of discussions & became a sort of touchstone. Students shared the poems they’d written & gave feedback: it’s better than Come On Lance, or, it’s not as good as Come On Lance, or, shades of Come On Lance. Then someone would ask to hear Come On Lance again & half the room would cheer & half the room would groan. Thanks James Brown for Come On Lance.

Hannah Mettner

My fave poetry thing all year has been the beautiful Heartache Festival that Hana Pera Aoake and Ali Burns put on at the start of the year! Spread over an afternoon and evening, across two Wellington homes, with readings and music and so much care and aroha. I wish all ‘literary festivals’ had such an atmosphere of openness and vulnerability!

Jane Arthur

Poetry-related things made up a lot of my highlights this year. I mean, obviously, winning the Sarah Broom Poetry Prize was … pretty up there. I’m still, like, “Me?! Whaaaat!” about it. I discovered two things after the win. First, that it’s possible to oscillate between happy confidence and painful imposter syndrome from one minute to the next. And second, that the constant state of sleep deprivation brought on by having a baby is actually strangely good for writing poetry. It puts me into that semi-dream-brain state that helps me see the extra-weirdness in everything. I wrote almost a whole collection’s worth of poems (VUP, 2020) in the second half of the year, thanks broken sleep!

A recent highlight for me was an event at Wellington’s LitCrawl: a conversation between US-based poet Kaveh Akbar and Kim Hill. I’m still processing all its gems – hopefully a recording will show up soon. Another was commissioning Courtney Sina Meredith to write something (“anything,” I said) for NZ Poetry Day for The Sapling, and getting back a moving reminder of the importance of everyone’s stories

This year I read more poetry than I have in ages, and whenever I enjoyed a book I declared it my favourite (I always do this). However, three local books have especially stayed with me and I will re-read them over summer: the debuts by Tayi Tibble and Sam Duckor-Jones, and the new Alice Miller. Looking ahead, I can’t wait for a couple of 2019 releases: the debut collections by essa may ranapiri and Sugar Magnolia Wilson.

Elizabeth Smither

Having Cilla McQueen roll and light me a cigarette outside the Blyth

Performing Arts Centre in Havelock North after the poets laureate

Poemlines: Coming Home reading (20.10.2018) and then smoking together,

cigarettes in one hand and tokotoko in the other. Then, with the relief that

comes after a reading, throwing the cigarette down into a bed of pebbles, hoping

the building doesn’t catch on fire.

Selina Tusitala Marsh

To perform my ‘Guys Like Gauguin’ sequence (from Fast Talking PI) in Tahiti at the Salon du Livre, between an ancient Banyan Tree and a fruiting Mango tree, while a French translator performs alongside me and Tahitians laugh their guts out!

Thanks Bougainville

For desiring ‘em young

So guys like Gauguin

Could dream and dream

Then take his syphilitic body

Downstream…

Chris Tse

This year I’ve been lucky enough to read my work in some incredible settings, from the stately dining room at Featherston’s Royal Hotel, to a church-turned-designer-clothing-store in Melbourne’s CBD. But the most memorable reading I’ve done this year was with fellow Kiwis Holly Hunter, Morgan Bach and Nina Powles in a nondescript room at The Poetry Cafe in London, which the three of them currently call home. It was a beautiful sunny Saturday that day, but we still managed to coax people into a dark windowless room to listen to some New Zealand poetry for a couple of hours. This is a poetry moment I will treasure for many years to come.

Sue Wootton

I’ve had the pleasure of hearing and reading plenty of poems by plenty of poets this year. But far and away the most rejuvenating poetry experience for me during 2018 was working with the children at Karitane School, a small primary school on the East Otago coast. I’m always blown away by what happens when kids embark on the poetry journey. Not only is the exploration itself loads of fun, but once they discover for themselves the enormous potentiality in language – it’s just go! As they themselves wrote: “Plant the seeds and grow ideas / an idea tree! Sprouting questions … / Bloom the inventions / Fireworks of words …” So I tip my cap to these young poets, in awe of what they’ve already made and intrigued to find out what they’ll make next.

Cilla McQueen

1

25.11.18

Found on the beach – is it a fossil?

jawbone? hunk of coral? No – it’s a wrecked,

fire-blackened fragment of Janola bottle,

its contorted plastic colonised by weeds

and sandy encrustations, printed instructions

still visible here and there, pale blue.

Growing inside the intact neck, poking out

like a pearly beak, a baby oyster.

2

Living in Bluff for twenty-two years now, I’ve sometimes felt out on a limb, in the tree of New Zealand poetry. I appreciate the journey my visitors undertake to reach me. A reluctant traveller myself, a special poetry moment for me was spent with Elizabeth Smither and Bill and Marion Manhire at Malo restaurant, in Havelock North. Old friends from way back – I haven’t seen them often but poetry and art have always connected us

Tayi Tibble

In September, I was fortunate enough to be able to attend The Rosario International Poetry Festival in Argentina. It was poetic and romantic; late night dinners in high rise restaurants, bottles of dark wine served up like water, extremely flowery and elaborate cat-calling (Madam, you are a candy!) and of course sexy spanish poetry and sexy poets.

On our last night, Marcela, Eileen and I broke off and went to have dinner at probably what is the only Queer vegan hipster restaurant/boutique lingerie store/experimental dj venue in the whole of Argentina, if not the world. Literally. We couldn’t find a vegetable anywhere else. We went there, because Eileen had beef with the chef at the last place and also we had too much actual beef generally, but I digress.

So anyway there we are eating a vegan pizza and platter food, chatting. I accidentally say the C word like the dumbass crass kiwi that I am forgetting that it’s like, properly offensive to Americans. Eileen says they need to take a photo of this place because it’s camp af. I suggest that Marcela and I kiss for the photo to gay it up because I’m a Libra and I’m lowkey flirting for my life because it’s very hot and I’ve basically been on a red-wine buzz for five days. Eileen gets a text from Diana, one of the festival organisers telling them they are due to read in 10 minutes. We are shocked because the male latin poets tend to read for up to 2584656 times their allocated time slots, so we thought we had plenty of time to like, chill and eat vegan. Nonetheless poetry calls, so we have to dip real quick, but when we step outside, despite it being like 1546845 degrees the sky opens up and it’s pouring down. Thunder. Lightening. A full on tropical South American storm!

It’s too perfect it’s surreal. Running through the rain in South America. Marcella and I following Eileen like two hot wet groupies. Telling each other, “no you look pretty.” Feeling kind of primal. Throwing our wet dark curls around. The three of us agree that this is lowkey highkey very sexy. Cinematic and climatic. Eventually we hail a taxi because time is pressing. Though later that night, and by night I mean at like 4am, Marcella and I, very drunk and eating the rest of our Vegan pizza, confessed our shared disappointment that we couldn’t stay in the rain in Argentina… just for a little while longer….

We get to the venue and make a scene; just in time and looking like we’ve just been swimming. Eileen, soaking wet and therefore looking cooler than ever, reads her poem An American Poem while Marcella and I admire like fangirls with foggy glasses and starry eyes.

“And I am your president.” Eileen reads.

“You are! You are!” We both agree.

Alison Glenny

A poetry moment/reading. ‘The Body Electric’ session at this year’s Litcrawl was a celebration of queer and/or non-binary poets (Emma Barnes, Harold Coutts, Sam Duckor-Jones, essa may ranapiri, Ray Shipley ). Curated and introduced by poet Chris Tse (looking incredibly dapper in a sparkly jacket) it was an inspiring antidote to bullying, shame, and the pressure to conform.

A book. Not a book of poetry as such, but a book by a poet (and perhaps it’s time to be non-binary about genre as well as gender?). Reading Anne Kennedy’s The Ice Shelf I was struck by how unerringly it highlights the salient characteristics of this strange era we call the anthropocene: crisis and denial, waste and disappearance, exploitation, and the destruction caused by broken relationships and an absence of care.

A publishing event. Seraph Press published the lovely tātai whetū: seven Māori women poets in translation, with English and Te Reo versions of each poem on facing pages (and a sprinkling of additional stars on some pages). An invitation, as Karyn Parangatai writes in her similarly bilingual review of the book in Landfall Review online (another publishing first?) ‘to allow your tongue to tease the Māori words into life’.

Best writing advice received in 2018. ‘Follow the signifier’.

essa may ranapiri

There are so many poetry highlights for me this year, so many good books that have left me buzzing for the verse! First book I want to mention is Cody-Rose Clevidence’s second poetry collection flung Throne. It has pulled me back into a world of geological time and fractured identity.

Other books that have resonated are Sam Ducker-Jone’s People from the Pit Stand Up and Tayi Tibble’s Poūkahangatus, work from two amazingly talented writers and friends who I went through the IIML Masters course with. After pouring over their writing all year in the workshop environment seeing their writing in book form brought me to tears. So proud of them both!

Written out on a type-writer, A Bell Made of Stones by queer Chamorro poet, Lehua M. Taitano, explores space, in the world and on the page. They engage with narratives both indigenous and colonial critiquing the racist rhetoric and systems of the colonial nation state. It’s an incredible achievement, challenging in form and focus.

I’ve been (and continue to be) a part of some great collaborative poetry projects, a poetry collection; How It Colours Your Tongue with Loren Thomas and Aimee-Jane Anderson-O’Connor, a poetry chapbook; Eater Be Eaten with Rebecca Hawkes, and a longform poetry zine; what r u w/ a broken heart? with Hana Pera Aoake. Working with these people has and continues to be a such a blessing!

I put together a zine of queer NZ poetry called Queer the Pitch. Next year I’m going to work to release a booklet of trans and gender diverse poets, I’m looking forward to working with more talented queer voices!

The most important NZ poetry book to be released this year, it would have to be tātai whetū. It was published as part of Seraph Press’s Translation Series. It features work from seven amazing wāhine poets; Anahera Gildea, Michelle Ngamoki, Tru Paraha, Kiri Piahana-Wong, Maraea Rakuraku, Dayle Takitimu and Alice Te Punga Somerville. These poems are all accompanied by te reo Māori translations of the work. I can only imagine that it would be a super humbling experience to have your work taken from English and returned to the language of the manu. By happenstance I was able to attend the launch of tātai whetū; to hear these pieces read in both languages was a truly special experience. It’s so important that we continue to strive to uplift Māori voices, new words brought forth from the whenua should be prized in our literary community, thanks to Seraph for providing such a special place for these poems. Ka rawe!

Anna Jackson

This has been a year of particularly memorable poetry moments for me, from the launch of Seraph Press’s bilingual anthology Tātai Whetū in March and dazzling readings by Mary Rainsford and Tim Overton at a Poetry Fringe Open Mike in April, to Litcrawl’s inspiring installation in November of essa may ranapiri and Rebecca Hawkes hard at work on their collaborative poetry collection in a little glass cage/alcove at the City Art Gallery. They hid behind a table but their creative energy was palpable even through the glass. I would also like to mention a poetry salon hosted by Christine Brooks, at which a dog-and-cheese incident of startling grace brilliantly put into play her theory about the relevance of improv theatre theory to poetry practice. Perhaps my happiest poetry moment of the year took place one evening when I was alone in the house and, having cooked an excellent dinner and drunken rather a few small glasses of shiraz, started leafing through an old anthology of English verse reading poems out loud to myself, the more the metre the better. But the poems I will always return to are poems I have loved on the page, and this year I have been returning especially to Sam Duckor-Jones’s People from the Pit Stand Up, while I look forward to seeing published Helen Rickerby’s breath-taking new collection, How to Live, that has already dazzled me in draft form.

happy summer days

and thank you for visiting my bog

in 2018

Cilla McQueen Poeta: selected and new poems Otago University Press 2018

Cilla McQueen’s new collection of poems is a treasure. The publisher has acknowledged Cilla’s standing as a poet by producing the most beautiful edition of poems out this year: hard back, gorgeous cover, exquisitely designed.

The poems are arranged in ‘rooms’ or preoccupations that form a thematic span and are largely chronological. The South Island landscape, cities and people are strong feature along with riddles, seasons, time, friendships, hens and the kitchen table. Some of my favourite poems by Cilla are here along with some delightful new discoveries. I have always admired her poetry with its deft musical chords, attention to detail and intimate moods. She has the ability to re-catch a moment or place that matters to her and allow it to shine for the reader.

Here again.

Dark’s falling. Stand

on the corner of the verandah

in the glass cold clear

night, looking out

to emerald and ruby harbour

lights

from ‘Homing In’ (1982)

This is the power of this anthology. It takes you to places and you become embedded in the scene.

thin waterskin over underfoot cockles here and there old timber

and iron orange and purple barnacled crab shells snails green

karengo small holes

from ‘Low Tide, Aramoana’ (1982)

You are also transported into the heart of friendships in poems that generate warmth and intimacy.

I visit my friend’s kitchen.

There are roses on the floor

and a table with pears.

Her face is bare in the light.

from ‘Joanna’ (2005)

I find these friendship poems moving as as though just in the moment of reading I am invited into a life.

Dear Hone, by your Matua Tokotoko

sacred in my awkward arms,

its cool black mocking

my shallow grasp

I was

utterly blown away

from ‘Letter to Hone’ (2010)

Cilla’s language is always on the move: pirouetting, linking, breaking, repeating, echoing, circling, defying gravity. Her poem ‘Anti Gravity’ takes me to self seeking bearings but also to a poem both establishing and defying them.

touch fingertips and out into

blue suede fields clear coloured with

dew sparkling prisms in sunlight

how fast the changes are

like balancing on a big beach ball

in bare feet running backwards

burnout she said aagh I thought burnout

sounds like a rocket stage falling away

from ‘Anti Gravity’ (1984)

I often read the ultra agile ‘Dog Wobble when I visit schools and the children are instantly alive with the possibility of words. Here she is being equally playful – the lines in the second stanza run in reverse order:

Poem a poem

the inside poem

the words other in

inside drawn eyeless

toe to top fingered

light, gnostic

valiant, innocent

fruit and rind.

from ‘Poem’ (2010)

There are also sections from Cilla’s terrific poetic memoir In a Slant Light published in 2016. I wrote a rave review about this book on my blog and wanted it win book awards and find a zillion readers.

Soup simmering on the coal range.

I’ve brought a loaf of bread. He pours red wine,

holds the glass up to the light.

Shades of red.

In harmony.

from In a Slant Light (2016)

There are so many rewarding routes through Cilla’s poetry ; I love the way she surprises then holds me as in ‘City Notes’ from 2017:

How much does the city weigh?

The earth beneath it shudders.

Thunderstorm kicking around.

They go on making concrete.

A recent poem invites us into her writing space which includes a study, a lounge and a kitchen, a view and the wind outside.

Sun bleached poetry spines. On the arm-rest of my chair lies a grey and white

baby possum’s skin, extremely soft to stroke.

Downstairs, etched on the glass door between the lounge and the kitchen, art

deco style, a slender dancing nymph.

The kitchen looks over the front lawn, low fence, footpath and the

road, a young cabbage tree beside the wooden letterbox.

from ‘Writing Place’ (2017)

This is a book to treasure. Cilla has won the NZ Book Award for Poetry three times, she has received an Hon. Litt. D. from the University of Otago and the Prime Minister’s Award for Poetry, and she was the New Zealand Poet Laureate 2009 -11. She lives in the southern port of Motupōhue near Bluff.

I love this book.

Otago University Press page