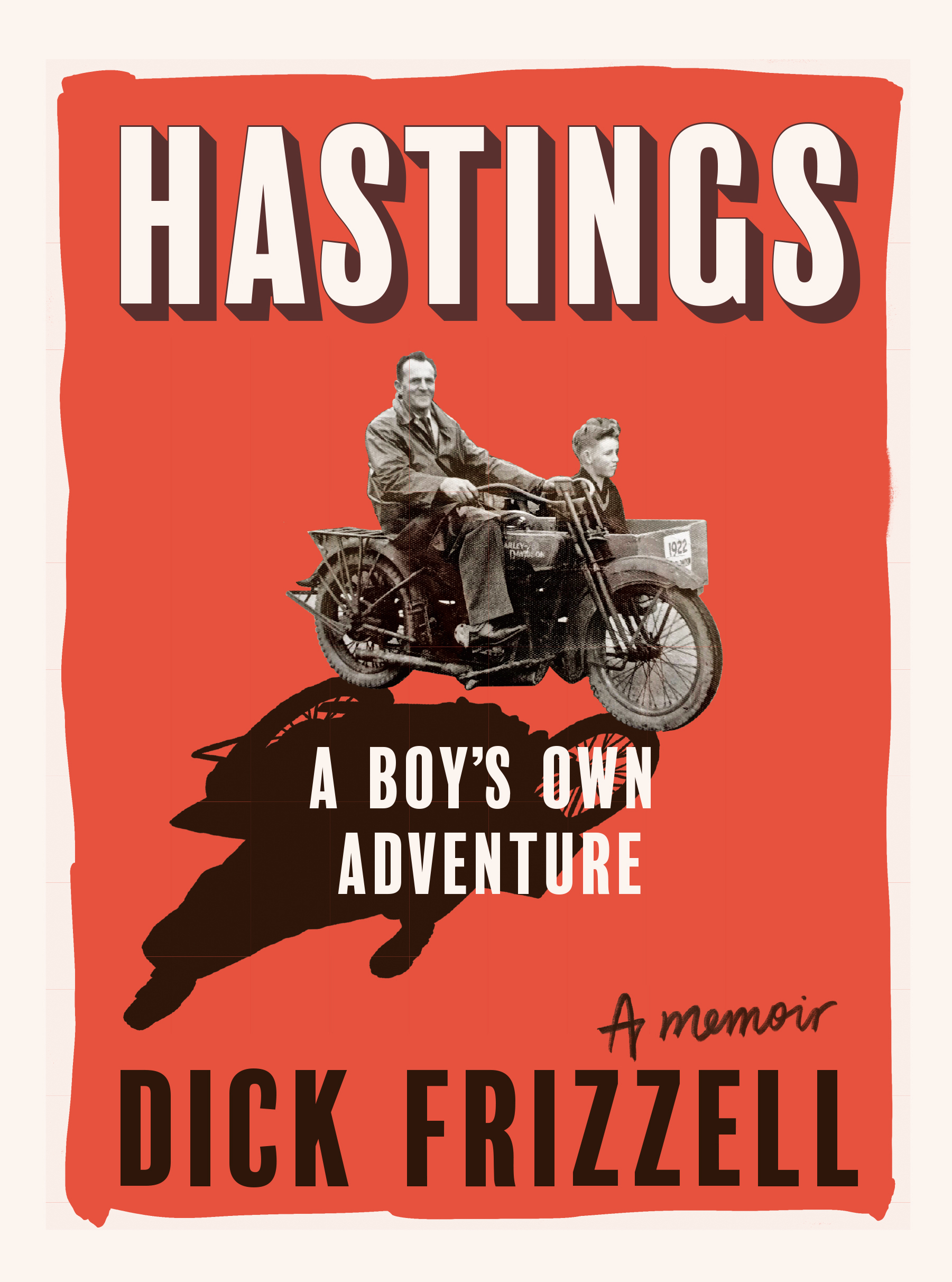

Hastings: A Boy’s Own Adventure, Dick Frizzell

Massey University Press, 2025

I purposefully saved Dick Frizzell’s new memoir, Hastings: A Boy’s Own Adventure, to read when Gow Langsford exhibition, ‘The Weight of the World’, was on. It’s not very often you get to inhabit an artist’s childhood and their latest work in the same viewing/reading. I am fascinated how the past can shine multiple lights on the present, and how the present can open fertile windows on the past.

Let me say from the outset, I adored the book and I adored the show. Dick begins his memoir with a key question: “How, or how not, to write a memoir? I’m slowly coming to the conclusion that there’s no right way to do it.” He opts to draw upon both truth and fiction: “a little memory, a little licence and a lot of humour”. He lays down a story frame guided by real life then fills in the gaps guided by imagination and wit. The result is an utterly readable voice, infused with an enthusiasm for life, for writing and for making art. An infectious voice, a voice that nails the rhythm of writing, speaking, revealing.

Dick was born in Auckland, moved to Hastings as a young boy, where he suggests living In Hastings, Napier, Clive and the Heretaunga plains felt like living at the centre of universe. It was a locus of escapades, delights and fascinations, with a drawcard library housing metaphorical and literal alleyways of ‘head-spinning’ books. There was the attraction to comics and a desire to copy them, the first encounter with paint on a tin roof, the school art room a beloved hideaway, shooting fish in a barrel, siblings galore, including a temporary stand-in brother.

There is a brilliant series of children’s books (Little Books, Big Dreams) published in the UK that offer miniature biographies of inspirational figures across time (Bob Marley, Virginia Woolf, Leo Messi, Frida Kahlo, Salvador Dali, David Attenborough to name a few). What I love about them, especially in these out-of-kilter times, is how they focus on childhood, on how sparks were ignited and seeds planted, often against all odds, and how the dreams of the child were allowed to find flight and anchor, and how the child could roam and delve and discover.

Reading Dick’s memoir I absorb a fascinating portrait of a time and place, within the shifting tides and trends of the 1950s and 1960s and, within that, the genesis of an artist. I am utterly moved by the portrait of Dick’s mother, a woman who was drawn to arts and craft, as so many women were of her generation, how a “she went to art school but was no bohemian”, stocked the house to the brim with art hobbies, played in skiffle bands, favoured the full glass of happiness. When Dick was in hospital after appendix surgery, his mum brought him art materials and everyone wanted him to draw them something. Wow!

Voice carries family, Robert Sullivan once said. Well voice carries memoir, and this memoir nails voice. It’s in the rhythm, it’s in the wit and detail, it’s in the grey areas (“Yes I know she was my mother, but who the hell was she?”). More than anything, it’s in the multiple dirt roads of boyhood that make an exhibition of landscape paintings even richer viewing.

Gate, 2025, oil on canvas, 700 mm x 900 mm

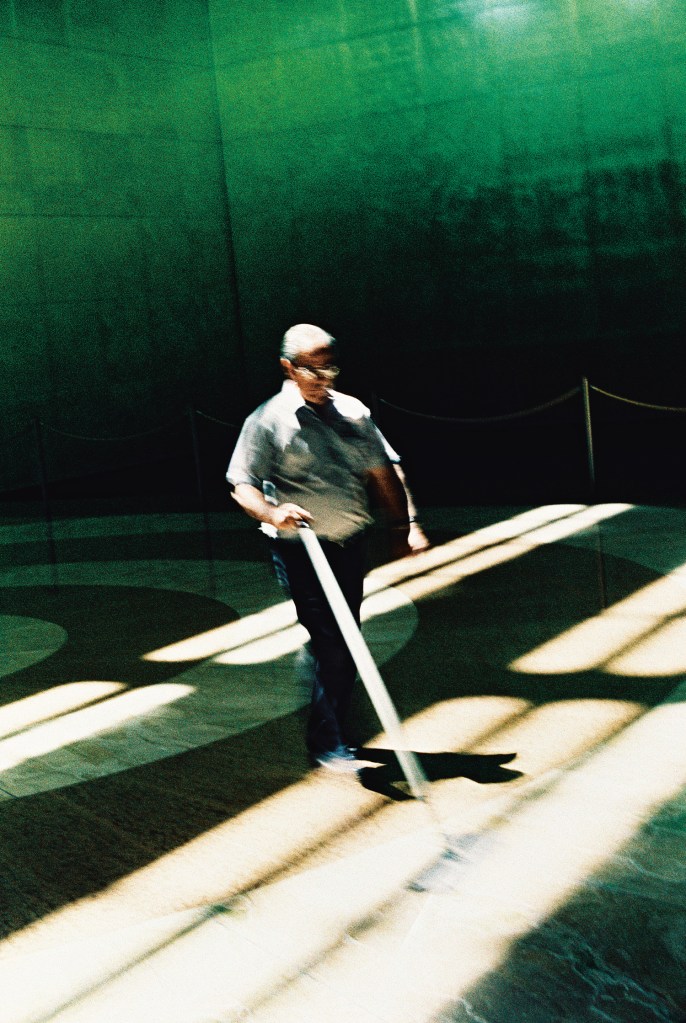

I am standing in the middle of Dick’s show, mesmerised. An opening chapter of the memoir places a map on Hastings, and this feels like a painterly map on experienced landscapes. How will I navigate my way through hills and sky and vegetation? Viewing art, like reading poetry, offers many trails, eye-catching vantage points, vital epiphanies. On this occasion, I am drawn into the familiar, a palette that is both restrained and vibrant, with shifting lights, the shimmer of brush upon hill and tree (especially trees!). I move from the intensified blue of a sky to shadows that loom across a wet paddock, loitering by a gate that invites (or forbids?) entry, almost feeling feet crunch into the texture of the dirt roads.

Why do I love this show so much? It’s not just standing within a nose-breath of the rural vistas, but finger-tapping lines of nostalgia. It’s admiring the visibility of brush stokes and painterly movement, and it’s the way each work is a repository for story. Where does this painting transport me? I get an extra taste of viewing uplift when I am at the show, sharing the space with a number of other captivated viewers. People are talking about the work nonstop, talking art, memory, story, place. One minute I am thinking the painting ‘Corn’ carries a whiff of Van Gogh and the next minute, a couple further along are saying the same thing. Everyone is talking paint and sky, tree and memory, and I wish Dick could witness it.

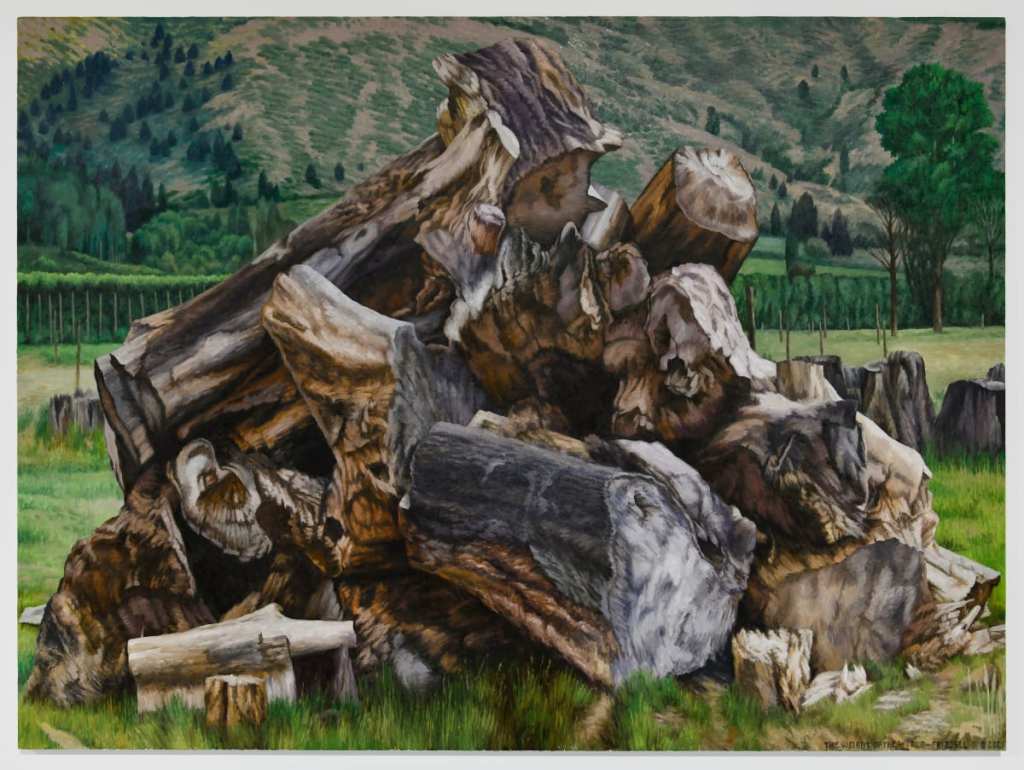

The Weight of the World, 2025, oil on canvas, 1800 mm x 2400 mm

I come back to the title of the show, which is also the title of a work. The painting features a huge stack of hacked tree stumps that block out the wider view and light, the everyday and the beauty that we see in the other paintings. This tree stump mound might be symbol or politics or personal anecdotes. Or simply cue the viewer to the visual attraction of gnarly muscular bark in a gnarly muscular pattern, that is taking visual delight in detail at a distance from postcard beauty. Yet couple the work’s title with one of the largest works in the show, ‘Milling Whakaangiangi’ (2025), it is impossible not to be reminded of the contentious deforestation of the land with its subsequent impact on soil and climate. The weight of the world indeed.

As reader, writer and spectator, I am boosted by art and poetry that gets me thinking, feeling, sidetracking. Heart mind eye, maybe even skin. Take ‘Sea View Castlepoint’, where the thin gap on the thin dirt road between the bulging trees affords a thin sea view, and there I go, sinking into the thin view as I widen it into the light of the world.

Sea View Castlepoint, 2025, oil on canvas, 700 mm x 900 mm

I am midway through Dick’s memoir as I view the show, and it feels like his paintings frame the landscape with a hint of the roving and fascinated eye of the child and his burgeoning creativity. Stop and view the trimmed hedge, the dark poplars, the whitebaiter’s huts, the dirt road, the wind swept tree, another dark tree. How easily I might become immune to my local landscape, the view out the car window, the paddocks up the road, but standing in the gallery space, absorbing the initial impact of light, colour and texture, I am immeasurably moved by the points of view, the way the gravel road hums with both journey and destination, the way an enthusiasm for comic books as a young boy, grew into myriad enthusiasms and, how on this occasion, an enthusiasm for patterns and detail in these experienced landscapes, in the quotidian and the physical, is utterly contagious. Wow!

Trimmed Hedge, 2024, oil on canvas, 400 mm x 500 mm

Massey University Press website

Gow Langsford Gallery website

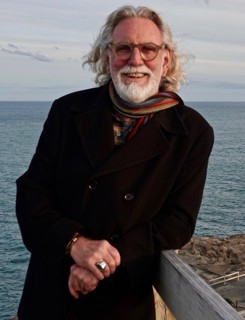

Dick Frizzell MNZM is one of New Zealand’s best-known painters. He studied at the Ilam School of Fine Arts at the University of Canterbury from 1960 to 1963 and then had a long career in advertising. Alongside his career as a painter, Frizzell is also the highly sought-after designer of a range of products from toys to wine. He is the author of Dick Frizzell: The Painter (Random House, 2009), It’s All About the Image (Random House, 2011) Me, According to the History of Art (Massey University Press, 2020) and The Sun Is A Star (Massey University Press, 2021). Dick exhibits regularly and often works in collaborations with writers and other artists. He lives in Auckland with his wife, Jude.

With a remarkably diverse repertoire of imagery and styles, Dick has created a unique body of work. His output includes works of landscape, cartoonish portraits, works of homage to notable artists including Picasso and McCahon, pointedly kitsch kiwiana, text-based artworks, abstract paintings, and much more. He has exhibited extensively, with career highlights that include the major travelling retrospective Dick Frizzell: Portrait of a Serious Artiste (City Gallery, Wellington, 1997), his residency in Antarctica as part of the Invitational Artist Programme (2005) and the publication of the monograph Dick Frizzell: The Painter (Random House NZ, 2009). His work is now held in collections throughout the country, most notably Christchurch Art Gallery, The Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery and Te Papa, Museum of New Zealand.