Gregory O’Brien at Tjibaou Cultural Centre, Noumea, March 2015

Photo Credit: Elizabeth Thomson

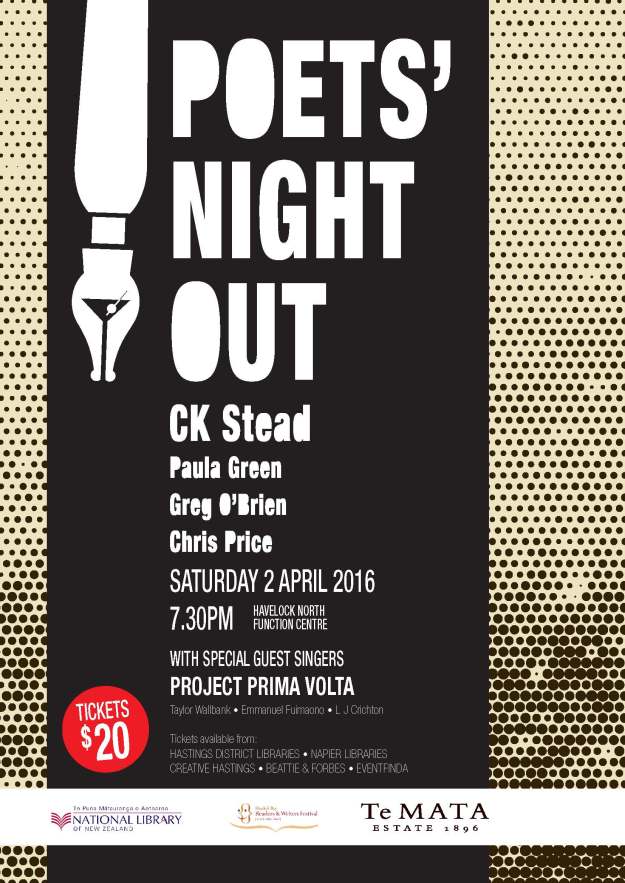

Gregory O’Brien is the 2015 Stout Memorial Fellow at the Stout Research Centre, Victoria University, where he is currently working on a book about poetry, painting and the environment. His new collection of poems is Whale Years (Auckland University Press). He has published numerous books of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. Since 2011 he has contributed to the ongoing Kermadec art project, works from which are on show at the Tjibaou Cultural Centre, New Caledonia, until July.

The interview

‘Ocean sound, what is it

you listen for?’

Did your childhood shape you as a poet? What did you like to read? Did you write as a child?

As far as I can recall, I drew more than I painted. And I always gravitated towards illustrated books—Tove Jansson’s ‘Moomin’ books stand out, and I remember The Lord of the Rings, as much for its illuminated maps as for the words. I went through a phase of reading comics—Whizzer & Chips rather than Batman. I date my interest in the interplay of words and visual images to those early encounters.

I doodled at every available opportunity and I remember being hauled out of class and punished for drawing, rather well, a crouching deer on the inside cover of my maths book. I usually captioned my drawings—so maybe those captions could be thought of as my first writings. Occasionally I filled in speech- or thought-balloons above various life-forms.

When you started writing poems as a young adult, were there any poets in particular that you were drawn to (poems/poets as surrogate mentors)?

I can trace this pretty exactly, I think. Aged 14: Bob Dylan’s ‘Writings & Drawings’. Aged 15: Dylan Thomas. Aged 16: James K. Baxter and Flann O’Brien (I liked to pretend Flann was an actual relative. I even screen-printed his book-title AT SWIM-TWO-BIRDS on a singlet—an item I still have in my wee box of treasures.) Aged 17: John Cage (Silence, and A Year from Monday). By the age of 18, I was living in Dargaville, and it was as if everybody suddenly jumped on board the NZ Road Services bus or bandwagon—I was reading Kenneth Patchen, William Blake, Edith Sitwell, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, e e cummings; also Allen Curnow, Janet Frame, Sam Hunt… I had known about Eileen Duggan for some years, because she was a relative, on my mother’s side. More than anything else, however, it was discovering Robin Dudding’s journal ISLANDS that turned my world around, that brought the whole business home…. Therein I discovered Ian Wedde, Bill Manhire, Elizabeth Smither, CK Stead…

Did university life transform your poetry writing? Theoretical impulses, research discoveries, peers?

I was six years out of school by the time I finished my BA, so my university life was mixed in, very much, with everything else that was going on: with 15 months in Dargaville, a year or so in Sydney… At university, I certainly wasn’t drawn to theory except in so far as I thought it was a grand imaginative game that might, periodically, yield unpredictable and outlandish results. I enjoyed the pottiness of Ezra Pound’s literary (rather than his political) theorising… An ABC of Reading is a great book. Probably the Zen-inclined John Cage and the Trappist Thomas Merton were the two non-fiction writers I held closest to me.

Reading your poetry makes me want to write. I love the way your poems delve deep into the world, surprisingly, thoughtfully yet never let go of the music of the line. Words overlap and loop and echo. There is an infectious joy of language at work. What are key things for you when you write a poem?

I listen to a lot of music. I want the poems to have something of the music that I love. I spend a lot of my time looking at art. And I want my poems to have something of the art that I love. There are aspects of composition, tone, rhythm and character which span all these different creative modes. Those are the key factors for me when I write… At a certain point, an appropriate form makes itself known…. The poem has to dive down into and surface from some essential state of being… There is certainly a joy in doing the things that you love; so there’s joy in the making and, preceding that, in the state of being that leads to the making….

Do you see yourself as a philosophical poet? Almost Zen-like at times?

My concept of philosophy is broad and shambolic enough to accommodate what I do as a writer. I’ve never read extensively in the field of Zen (apart from the books of John Cage and the writing of my friend Richard von Sturmer). I’ve read a little, and somewhat randomly, in the field of non-conformist Catholic thought: Simone Weill, Meister Eckhart, Merton, Baxter… These peregrinations may have affected me more than I realise or am prepared to say.

Do you think your writing has changed over time?

I guess writing has to evolve – otherwise it will become predictable and a total drag. I’m as entranced as I ever was with the process, the business, the labour of it. At the same time, I remain devoted to the finished form of it: The printed book, with its covers and half-title and title-page; and the shapes of words on the page and maybe illustrations. Poetry is an art that, if it’s working, is constantly reinventing itself.

I look back at my early poems and find fault. I find myself blaming an over-voracious intake of French Surrealism; too much Kenneth Patchen one year, too much Stevie Smith the next… Too much John Berryman! And, next year, not enough John Berryman! But the ship sails on, and finds new oceans to ply.

You write in a variety of genres (poetry, non-fiction, critical writing). Do they seep into each other? Your critical writing offers the reader a freshness of vision and appraisal – not just at the level of ideas but the way you present those ideas, lucidly, almost poetically. Does one genre have a particular grip on you as a writer?

I’m only starting to realise the inter-relatedness of these different genres. A few years back I started to explore poetry’s potential to carry information, also to elaborate upon a thought in a more detailed kind of way, ie. to have an almost essayistic function. So quite a few of my longer poems (some of the odes and, particularly, ‘Memory of a fish’ in my new book) are laden with facts, figures and reasonably clearly articulated information.

Needless to say poetry infuses the writing I produce in relation to the visual arts. I find looking at art exciting; it appeals to my poetic self. I don’t really have a critical self. I hope my non-fiction writing has a cadence, a music and a subconscious (rather than a conscious) purposefulness. Pondering my recent writings on artists such as Pat Hanly, Barry Brickell and Michael Hight, I remember in each case hearing a note—a song, almost—in my ear, and I was beholden to it.

Do you think we have a history of thinking and writing about the process of poetry? Any examples that sparked you?

James K. Baxter wrote wonderfully about writing poetry. Bill Manhire’s Doubtful Sounds is an immensely useful and energising book. 99 Ways Into New Zealand Poetry is terrific too. I refer back to my set of the journal ISLANDS and, yes, it seems to me we New Zealanders have been writing about the process as well as the product. Janet Frame’s oeuvre might be our greatest, most enduring instance of writing about writing, thinking about writing, writing about thinking, and thinking about thinking.

Your poetry discussions with Kim Hill are terrific. The entries points into a book are paramount; the way you delight in what a poem can do. What is important for you when you review a book?

I think a book has to become part of your life to really make an impression. It’s the same with music or visual arts. It can’t be a purely intellectual thing, it has to take you over, to some degree. It has to be disarming. Accordingly I tend not to discuss books that don’t ‘do it’ for me. Life’s too short. Fortunately, I have catholic tastes. There are things I enjoy very much in Kevin Ireland, as there are things I enjoy in Michele Leggott. I guess this makes me a lucky guy.

I agree wholeheartedly. I am not interesting in reviewing books on Poetry Shelf unless they have caught me, stalled me (for good reasons!).

What poets have mattered to you over the past year? Some may have mattered as a reader and others may have been crucial in your development as a writer?

Two years ago I went to Paris and met up with one of my all-time heroes, the French poet and art-writer Yves Bonnefoy. He turned 90 last year (Joyeux anniversaire, Yves!) During my recent travels around the Pacific (from New Caledonia to Chile), I’ve taken bilingual editions of Yves with me everywhere. I am interested in the way he has turned the creative conundrum of being an Art Writer and a Poet into something unified and compelling (channelling earlier French poet-art-writers from Baudelaire to Apollinaire, with a nod to Yves’s near-contemporaries, that wondrous group of wanna-be French-art-poets, John Ashbery and the New Yorkers). I also took the poems of Neruda and Borges with me everywhere I went.

What New Zealand poets are you drawn to now?

New Zealand poetry is interesting at the moment. It’s all over the place. As it should be. There are plenty of people I read voraciously. As well as the poets mentioned already: Anna Jackson, Vince O’Sullivan, you Paula, Lynn Davidson, Kate Camp, Geoff Cochrane… Last year I edited a weekly column for the Best American Poets website—that was a good chance to ‘play favourites’, as Kim Hill would say. (All those posts are archived here: http://blog.bestamericanpoetry.com/the_best_american_poetry/new-zealand/) There are some great first books appearing at the moment: Leilani Tamu’s The Art of Excavation; John Dennison’s Otherwise. This bodes very well indeed.

Name three NZ poetry books that you have loved recently.

I was rereading Riemke Ensing’s Topographies (with Nigel Brown’s illustrations) the other day; I found that book very inspiring when it appeared way back in 1984. Lately I’ve also been reading Bob Orr’s crystalline Odysseus in Woolloomooloo and Peter Bland’s Collected Poems… I could go on.

Your new collection, Whale Years, satisfies on so many levels. These new poems offer a glorious tribute to the sea; to the South Pacific routes you have travelled. What discoveries did you make about poetry as you wrote? The world? Interior or external?

The Kermadec voyage, and subsequent travels—most recently to New Caledonia—opened up a huge areas of subjective experience as well as of human and natural history. How do you write about that kind of space, that energy, that life-force? Wherever you travel, the air is different; the ‘night’ has a different character; the smells and textures of the vast Pacific vary from place to place. And people move differently wherever you go – they claim a different kind of space within the environment. My recent travels have been like a door opened on a new world. The last three years of my poetry-writing have been the most intense since I was in my early twenties.

That shows in this book Greg. I am looking forward to reviewing it because it touched a chord in so many ways. I love the idea that poems become little acts of homage. What difficulties did you have as traveller transforming ‘elsewhere’ into poetry? To what degree do you navigate poetry/other place as trespasser, tourist, interloper?

The artist Robin White likes to point out that there is only one ocean on earth. All our oceans are joined together—it’s the same body of water. So, if you take the sea to be your home (which, as Oceanians, believe it or not, we should do), then as long as you’re at sea you’re still, to some degree, in your home environment.

As a poet entering a new environment, I bring with me my responses, my eye, my mind and various kinds of baggage. I’m a curious person by nature so I always want to find new things—things I don’t know anything about. I like it when my preconceptions fall apart. I love being wrong about things; I enjoy the subsidence of the known world. I quote the great post-colonialist writer Wilson Harris in Whale Years: ‘If you can tilt the field then you will dislodge certain objects in the field and your own prepossessions may be dislodged as well.’

I feel that, as a poet, I am most in my element when I am sitting on the ground and learning new things. When the field of the known has been tilted. And filling my notebooks with various tracings of that new knowledge or sensation.

This is a good way to look poetry that takes hold of you; it ‘tilts’ you. I also loved the elasticity of your language – the way a single word ripples throughout a poem gleaning new connections and possibilities. Or the way words backtrack and loop. At times I felt a whiff of Bill Manhire, at others Gertrude Stein. Yet a poem by Gregory O’Brien is idiosyncratic. Are there poets you feel in debt to in terms of the use of language?

Strangely, I can’t read Gertrude Stein anymore. She is one of a very few writers I have been in love with and then the relationship has waned. Maybe, early on, she loosened up my use of language, the extent to which the rational mind is left to run things. There was a music I found in Stein, for sure. But this was something—increasingly—I found in more conventional writers like Wallace Stevens, Robert Creeley and, most recently, in Herman Melville. Moby Dick is a piece of great, symphonic, oceanic music. The novel (for want of a better term) is an incredible noise, a racket of spoken and sung sounds. Melville’s style reminds me of all the depth-finders, radars, monitors and gauges on the bridge of HMNZ Otago as we sailed north to Raoul Island in May 2011. All that information pinging and popping…

Is there a single poem or two in the collection that particularly resonates with you?

The long poem, ‘Memory of a fish’, is the piece that connects various experiences from the three year period in which the book was written, and brings them together—in an essayistic fashion, almost. I enjoy the ebb and flow of the triplets, and the world’s details tripping along them, like things washing ashore on Oneraki Beach… When I was writing that poem I felt I was living inside it, totally. And I haven’t quite climbed out of it yet, to be honest.

The book also demonstrates that eclectic field you plunge into as a reader with its preface quotes. What areas are you drawn into at the moment? Any astonishing finds?

The quotations at the beginning of the three sections of the book are constellations in the night sky above the poetry-ground. They mark points of reference, further co-ordinates, which have guided the writing: W. S. Graham’s ‘The stones roll out to shelter in the sea.’ The Flemish proverb: ‘Don’t let the herring swim over your head.’ Those are verbal artefacts I have carried around with me, much as you would pick up a shell or a colourful leaf. They were/are talismans. So I have stored them inside the book as well. Cherished things.

‘Constellation’ is perfect. I was thinking underground roots that nourish. Or one of any number of maps you can lay over the poems (the map of domestic intrusion, the map of childhood, the map of objects, the map of reading). But yes the process of writing has its constellation-guides as you venture into and from both dark and light.

Poetry finds its way into a number of your paintings (as it does with John Pule). There are a number of drawings included in the book that add a delicious visual layer. How do you negotiate the relationship between painting and poetry? Does one matter more? Do they feed off each other?

My notebooks contain a thick broth of visual and verbal ingredients. These materials arrive in my journal simultaneously. When writing or painting, I separate the words from the visual images and work on them more-or-less separately. When it comes to putting together a book, like Whale Years, these two disparate activities are reunited again. I’ve always loved illustrated books. (I think immediately of Bill Manhire’s The Elaboration, with pictures by Ralph Hotere; Blaise Cendrars’ long Trans-Siberian poem, illustrated by Sonia Delaunay; William Blake illustrating himself, and so on)

NOTES ON THE RAISING OF THE BONES OF PABLO NERUDA AT ISLA NEGRA by John Reynolds & Gregory O’Brien, etching, 2014

You have collaborated with a number of other artists and writers. What have been the joys and pitfalls of collaboration?

There are no pitfalls, as far as I can see. Somehow, I’ve found my way into a few collaborative circumstances and very much enjoyed the results. In the past year I’ve made etchings with my two painter-friends John Reynolds and John Pule. Like Charles Baudelaire and Frank O’Hara before me, I seem to have been lucky enough to fall in with a good crowd of painters (and also photographers—but that’s another story).

SAILING TO RAOUL by John Pule & Gregory O’Brien, etching, 2012 (John titled this work, riffing off Yeats’s ‘Sailing to Byzantium’)

The constant mantra to be a better writer is to write, write, write and read read read. You also need to live! What activities enrich your writing life?

Certainly my recent travels around the Pacific have been hugely enriching. I’m not a proper swimmer, but since I was a child I have had a great passion for floating in, or being upon salt water. (My book News of the Swimmer Reaches Shore grew out of that propensity.) The everydayness of existence is the most enriching thing—as the poems of Horace and Neruda and Wedde keep reminding me. What a great and pleasant swarm of information and sensation we find ourselves amidst, every day of our lives.

Finally if you were to be trapped for hours (in a waiting room, on a mountain, inside on a rainy day) what poetry book would you read?

I keep coming back to the Collected Poems of James K. Baxter. Not because it’s the best book ever written but because of the simple fact that it occupies a huge and resonant place in my life.

Auckland University Press page

New Zealand Book Council page

Arts Foundation page

The Kermadecs page

National Radio page (discussing poetry highlights of 2014 with Kim Hill)