Category Archives: NZ poetry

Poetry Shelf noticeboard: National Poetry Slam winner Te Kahu Rolleston performs some of his poetry and speaks with Kathryn Ryan

Leave a reply

Wonderful radio!

National Poetry Slam winner Te Kahu Rolleston performs some of his poetry and speaks with Kathryn Ryan about giving rangatahi voice to hopes and dreams through performance poetry. E Tū Whānau is running a spoken word competition, the kaupapa being “hopes and dreams for my world, my future, my whānau”. Te Kahu’s offering tips and encouraging everyone to enter and get involved. He’s no stranger to enthusing young people. Listen duration 31′ :32″ Add to playlistDownload

Alumni of the prestigious Banff Centre’s Indigenous Writing Programme, Te Kahu runs spoken word workshops with rangatahi in schools around the country to endear them to a life-long love of reading and spoken word poetry. Te Kahu’s approach is to fill the room with joy and happiness, so learning – and writing – is a joy.

Poetry Shelf celebrates new books: Editor Pat White reads from Rejoice Instead: the Collected Poems of Peter Hooper

Rejoice Instead: the Collected Poems of Peter Hooper, ed and introd by Pat White,

Cold Hub Press, 2021

Pat White reads from Rejoice Instead (Part One)

Pat White reads from Rejoice Instead (Part Two)

Peter Hooper (1919–1991): was a West Coast poet, novelist, teacher, bookseller and conservationist. In a writing career that spanned the decades following World War II until his death in 1991, his reputation as a poet has tended to depend on poems published in slim volumes no longer easily accessible. The exception was Earth Marriage (Fragments III, 1972), a selection of previously published and new work with photographs of the West Coast, which sold two thousand copies within a year. A rather meagre Selected Poems was published by John McIndoe in 1977. Between 1977 and his death in 1991 Hooper published a trilogy of novels: A Song in the Forest (1979); People of the Long Water (1985); and Time and the Forest (1986) which won the New Zealand Book Award for fiction. A collection of short stories, The Goat Paddock and other stories appeared in 1981. Hooper also wrote and published extensively on conservation and environmental subjects.

Pat White is a writer and artist living near Fairlie. He has an MFA from Massey University, and an MA in Creative Writing from IIML Victoria University. In August 2018 Roger Hickin’s Cold Hub Press published Watching for the Wingbeat; new & selected poems. In 2017 Notes from the margins, his biography/memoir of the teacher, author, environmentalist, the West Coast’s Peter Hooper, was published. An exhibition, Gallipoli in search of family story, has been shown in museums and art galleries a number of times in recent years.

Cold Hub Press page

Pat White discusses Rejoice Instead: Collected Poems: Peter Hooper with Lynn Freeman on RNZ National

Poetry Shelf Theme Season: Twelve poems about kindness

Kindness, the word on our tongues, in this upheaval world, in these challenging times, as we navigate conflicting points of view, when our well being is under threat, when the planet is under threat, when some of us are going hungry, cold, without work, distanced from loved ones, suffer cruelty, endure hatred because of difference. Kindness is the word and kindness is the action, and it is the leaning in to understand. I had no idea what I would discover when I checked whether poetry features kindness, and indeed, at times, whether poems are a form of kindness. I think of poetry as a form of song, as excavation, challenge, discovery, tonic, storytelling, connection, as surprise and sustenance for both reader and writer. In the past year, as I face and have faced multiple challenges, poetry has become the ultimate kindness.

The poems I have selected are not necessarily about kindness but have a kindness presence that leads in multiple directions. Warm thanks to the poets and publishers who have supported my season of themes. The season ends mid August.

The poems

Give me an ordinary day

Ordinary days

Where the salt sings in the air

And the tūī rests in the tree outside our kitchen window

And the sun is occluded by cloud, so that the light

does not reach out and hurt our eyes

And we have eaten, and we have drunk

We have slept, and will sleep more

And the child is fed

And the books have been read

And the toys are strewn around the lounge

Give me an ordinary day

Ordinary days

Where I sit at my desk, working for hours

until the light dims

And you are outside in the garden,

clipping back the hedge and trees

And then I am standing at the sink, washing dishes,

And chopping up vegetables for dinner

We sit down together, we eat, our child is laughing

And you play Muddy Waters on the stereo

And later we lie in bed reading until midnight

Give me an ordinary day

Ordinary days

Where no one falls sick, no one is hurt

We have milk, we have bread and coffee and tea

Nothing is pressing, nothing to worry about today

The newspaper is full of entertainment news

The washing is clean, it has been folded and put away

Loss and disappointment pass us by

Outside it is busy, the street hums with sound

The children are trailing up the road to school

And busy commuters rush by talking on cellphones

Give me an ordinary day

And because I’m a dreamer, on my ordinary day

Nobody I loved ever died too young

My father is still right here, sitting in his chair,

where he always sits, looking out at the sea

I never lost anything I truly wanted

And nothing ever hurt me more than I could bear

The rain falls when we need it, the sun shines

People don’t argue, it’s easy to talk to everyone

Everyone is kind, we all put others before ourselves

The world isn’t dying, there is life thriving everywhere

Oh Lord, give me an ordinary day

Kiri Piahana-Wong

The guest house

(for Al Noor and Linwood Mosques)

In this house

we have one rule:

bring only what you want to

leave behind

we open doors

with both hands

passing batons

from death to life

come share with us

this tiny place

we built from broken tongues

and one-way boarding passes

from kauri bark

and scholarships

from kāitiaki

and kin

in this house

we are

all broken

all strange

all guests

we are holding

space for you

stranger

friend

come angry

come dazed

come hand against your frail

come open wounded

come heart between your knees

come sick and sleepless

come seeking shelter

come crawling in your lungs

come teeth inside your grief

come shattered peace

come foreign doubt

come unrequited sun

come shaken soil

come unbearable canyon

come desperately alone

come untuned blossom

come wild and hollow prayer

come celestial martyr

come singing doubt

come swimming to land

come weep

come whisper

come howl into embrace

come find

a new thread

a gentle light

a glass jar to hold

your dust

come closer

come in

you are welcome, brother

Mohamed Hassan

from National Anthem, Dead Bird Books, 2020

Prayer

I pray to you Shoulder Blades

my twelve-year-old daughter’s shining like wings

like frigate birds that can fly out past the sea where my father lives

and back in again.

I pray to you Water,

you tell me which way to go

even though it is so often through the howling.

I pray to you Static –

no, that is the sea.

I pray to you Headache,

you are always here, like a blessing from a heavy-handed priest.

I pray to you Seizure,

you shut my eyes and open them again.

I pray to you Mirror,

I know you are the evil one.

I pray to you Aunties who are cruel.

You are better than university and therapy

you teach me to write books

how to hurt and hurt and forgive,

(eventually to forgive,

one day to forgive,

right before death to forgive).

I pray to you Aunties who are kind.

All of you live in the sky now,

you are better than letters and telephones.

I pray to you Belt,

yours are marks of Easter.

I pray to you Great Rock in my throat,

every now and then I am better than I am now.

I pray to you Easter Sunday.

Nothing is resurrecting but the water from my eyes

it will die and rise up again

the rock is rolled away and no one appears

no shining man with blonde hair and blue eyes.

I pray to you Lungs,

I will keep you clean and the dear lungs around me.

I pray to you Child

for forgiveness, forgiveness, forgiveness.

I will probably wreck you as badly as I have been wrecked

leave the ship of your childhood, with you

handcuffed to the rigging,

me peering in at you through the portholes

both of us weeping for different reasons.

I pray to you Air

you are where all the things that look like you live

all the things I cannot see.

I pray to you Reader.

I pray to you.

Tusiata Avia

from The Savage Coloniser Book, Victoria University Press, 2020

sonnet xix

I’m thinking about it, how we’ll embrace each other

at the airport, then you’ll drive the long way home,

back down the island, sweet dear heart, sweet.

And I’m thinking about the crazy lady, how she strides

down Cuba Mall in full combat gear,

her face streaked with charcoal, how she barges

through the casual crowd, the coffee drinkers,

the eaters of sweet biscuits. ‘All clear,’ she shouts,

‘I’ve got it sorted, you may all stand down.’

What I should do, what I would do if this was a movie,

I’d go right up to her and I’d say, ‘Thank you,

I feel so much safer in this crazy world with you around.’

Geoff would get it, waiting at the corner of Ghuznee Street.

It’s his kind of scene. In fact, he’d probably direct it.

Bernadette Hall

from Fancy Dancing: Selected Poems, Victoria University Press, 2020

Precious to them

You absolutely must be kind to animals

even the wild cats.

Grandad brought me a little tiny baby hare,

Don’t you tell your grandma

I’ve brought it inside and put it in the bed.

He put buttered milk arrowroot biscuits, slipped them

in my pockets to go down for early morning milking

You mustn’t tell your grandma, I’m putting all this butter

in the biscuits.

Marty Smith

from Horse with Hat, Victoria University Press, 2014, suggested by Amy Brown

kia atawhai – te huaketo 2020

kia atawhai ki ā koutou whānau

kia atawhai ki ā koutou whanaunga

kia atawhai ki ā koutou hoa

kia atawhai ki ā koutou kiritata

kia atawhai ki ā koutou hoamahi

kia atawhai ki ngā uakoao

kia atawhai ki ngā tangata o eru ata mātāwaka

kia atawhai ki ā koutou ano.

ka whakamatea i te huaketo

ki te atawhai.

kia atawhai.

be kind – the virus 2020

be kind to your families

be kind to your relatives

be kind to your friends

be kind to your neighbours

be kind to your workmates

be kind to strangers

be kind to people of other ethnicities

be kind to yourselves.

kill the virus

with kindness.

be kind.

Vaughan Rapatahana

The Lift

For Anna Jackson

it had been one of those days

that was part of one of those weeks, months

where people seemed angry

& I felt like the last runner in the relay race

taking the blame for not getting the baton

over the finish line fast enough

everyone scolding

I was worn down by it, diminished

& to top it off, the bus sailed past without seeing me

& I was late for the reading, another failure

so when Anna offered me a lift home

I could have cried

because it was the first nice thing

that had happened that day

so much bigger than a ride in a car

it was all about standing alone

in a big grey city

and somebody suddenly

handing you marigolds

Janis Freegard

first appeared on Janis’s blog

Honest Second

The art of advice

is balancing

what you think

is the right thing

with what you think

is the right thing to say,

keeping in mind

the psychological state

of the person whom you are advising,

your own integrity and beliefs,

as well as the repercussions

of your suggestions in the immediate

and distant futures—a complex mix,

especially in light of the fact that friendship

should always be kind first,

and honest second.

Johanna Emeney

from Felt, Massey University Press, 2021

A Radical Act in July

You are always smiling the cheese man says, my default position.

The cheese, locally made, sold in the farmers market,

but still not good enough for my newly converted vegan friend

who preaches of bobby calves, burping methane, accuses me

of not taking the problems of the world seriously enough.

Granted, there is much to be afraid of: unprecedented fires,

glaciers melting, sea lapping into expensive living rooms,

the pandemic threatening to go on the rampage again

and here still, lurking behind supermarket shelves,

or in the shadows outside our houses like a violent ex-husband.

Strongmen, stupid or calculating are in charge of too many countries,

we have the possibility of one ourselves now, a strong woman,

aiming to crush our current leader and her habit of kindness

while she holds back global warming and Covid 19

with a scowl. I can see why friends no longer watch the news,

why my sons say they will have no children,

why pulling the blankets over your head starts to seem

like a reasonable proposition but what good does that do

for my neighbour living alone, who, for the first time

in her long-life, surviving war, depression

and other trauma is afraid to go outside?

Perhaps there is reason enough for me not to smile,

one son lives in China and can’t come back for the lack

of a job. The other lives by the sea, but in a shed with no kitchen.

I hear my stretcher-bearer dad in his later years, talking

of Cassino and how they laughed when they weren’t screaming

how his mates all dreamed of coming home and finding

a girl. Some did and so we are here, and in being here

we have already won the lottery. So, I get up early

for the market, put on my red hat to spite the cold,

and greet the first crocus which has popped up overnight.

I try not to think it’s only July and is this a sign

and should I save the world by bypassing the cheese man

and the milk man who names his cows?

My dad was consumed by nightmares most of his life,

but at my age now, 69, he would leap into the lounge

in a forward roll to shock us into laughing. A gift,

though I didn’t see it at the time. Reason enough to smile,

practise kindness and optimism as a radical act

Diane Brown

Seabird

I have not forgotten that seabird

the one I saw with its wings

stretched across the hard road.

One eye open,

one closed.

I wanted to walk past

But the road is no place

for a burial –

I picked it up by the wings

took it to the

water and floated it

out to sea,

which was of no use

to the bird, it had ceased.

I like to think someone

was coaching me in the small,

never futile art,

of gentleness.

Richard Langston

from Five O’Clock Shadows, The Cuba press, 2020

Four stories about kindness

I had lunch with Y today, and she told me over gnocchi (me) and meatballs (her), about how she joined up with another dating website. She quickly filled in the online forms, all the ones about herself and her interests, until she came to one where she had to choose the five attributes she thought were the most important in a person. She looked at them for a while, and then grabbed a piece of paper and wrote out the thirty possible attributes in a list. She read the list. She put it down and went to bed. The next morning when she woke up she read the list again. She found her scissors and snipped around each word. She laid each rectangle on the table, arranged them in a possible order, shuffled them around, and then arranged them again. She went to work. When she came back in the evening they were still there, glowing slightly in the twilight. She sat down in front of them and made some minor adjustments. She discovered, somewhat to her surprise, that kindness is the most important thing to her. She went back to the web page and finished her application. Very soon she was registered and had been matched with ten men in her area. Soon after she had thirty-five messages. The next morning she had forty more. She deleted the messages and deleted her profile. Then she wrote five words on a piece of paper and pinned it to her wall.

*

I phone A, whose father is dying. Whether fast or slow, no one really knows, and no one wants to say it, but we all know this will probably be his last Christmas. She was, at this very moment, she tells me, writing in our Christmas card. She tells me that she’s been thinking a lot about kindness. About people who are kind even when it’s inconvenient, even when it hurts. I tell her she is a kind person. ‘There are times’, she says, ‘when I could have chosen to be kind, but I didn’t. Wasn’t. I’ve said things. Done things. I don’t want to do that – I don’t want to make people feel small.’ I think of my own list, my own regrets. It’s weeks later before we get our Christmas card. ‘What’s this word here?’ asks S, as he reads it. ‘Before lights.’ ‘Kind’, I say. ‘The word is kind.’

*

J is a scientific sort of person, and she wants to understand relationships, so she does what any good scientist would do and keeps a notebook in which she records her observations. She watches. And listens. And then she writes. She writes about the good ones, and about the bad ones. Her subjects are her friends, her family, her acquaintances and people she meets (or overhears) while travelling. None of them have given ethics approval. (She hasn’t asked.) She considers the characteristics of each relationship, both good and bad, and in-between. It is almost halfway through New Year’s Day and we are still eating breakfast. While her study is not yet finished, and so all results are of course provisional, she tells us one thing is clear to her already: that the characteristic shared by the best relationships is kindness.

*

I am talking to C in the back yard at the party and I tell him that the theme of the moment is kindness. He tells me that while, yes, he thinks kindness is important, he thinks he is sometimes (for which I read ‘often’) too kind. He puts up with things, he says, that he should not. He lets people have their way. He doesn’t want to hurt their feelings, but he doesn’t want to be a doormat anymore. I’m not always the quickest thinker, but I know there is something wrong here; I think I know that there is a difference between kindness and niceness, kindness and martyrdom. I am sure that being kind doesn’t mean giving in, going along with things you don’t like, denying yourself. I’m sure that being kind doesn’t mean you can’t give the hard word, when needed, doesn’t mean condoning bad behaviour. I try to explain this to C, who is kind, and also is a doormat sometimes, but I’m not sure he understands what I’m saying. I’m not sure if he heard me. Probably because we are both too busy giving each other advice.

Helen Rickerby

from How to Live, Auckland University Press, 2019

Letter to Hone

Dear Hone, by your Matua Tokotoko

sacred in my awkward arms,

its cool black mocking

my shallow grasp

I was

utterly blown away.

I am sitting beside you at Kaka Point

in an armchair with chrome arm-rests

very close to the stove.

You smile at me,

look back at the flames,

add a couple of logs,

take my hand in your bronze one,

doze awhile;

Open your bright dark eyes,

give precise instructions as to the location of the whisky bottle

on the kitchen shelf, and of two glasses.

I bring them like a lamb.

You pour a mighty dram.

Cilla McQueen

from The Radio Room, Otago University Press, 2010

The poets

Tusiata Avia is an internationally acclaimed poet, performer and children’s author. She has published 4 collections of poetry, 3 children’s books and her play ‘Wild Dogs Under My Skirt’ had its off-Broadway debut in NYC, where it took out The Fringe Encore Series 2019 Outstanding Production of the Year. Most recently Tusiata was awarded a 2020 Arts Foundation Laureate and a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to poetry and the arts. Tusiata’s most recent collection The Savage Coloniser Book won The Ockham NZ Book Award for Best Poetry Book 2021.

Diane Brown is a novelist, memoirist, and poet who runs Creative Writing Dunedin, teaching fiction, memoir and poetry. She has published eight books: two collections of poetry – Before the Divorce We Go To Disneyland, (Jessie Mackay Award Best First Book of Poetry, 1997) Tandem Press 1997 and Learning to Lie Together, Godwit, 2004; two novels, If The Tongue Fits, Tandem Press, 1999 and Eight Stages of Grace, Vintage, 2002—a verse novel which was a finalist in the Montana Book Awards, 2003. Also, a travel memoir, Liars and Lovers, Vintage, 2004; and a prose/poetic travel memoir; Here Comes Another.

Johanna Emeney is a senior Tutor at Massey University, Auckland. Felt (Massey University Press, 2021) is her third poetry collection, following Apple & Tree (Cape Catley, 2011) and Family History (Mākaro Press, 2017). You can find her interview with Kim Hill about the new collection here and purchase a book directly from MUP or as an eBook from iTunes or Amazon/Kind.

Janis Freegard is the author of several poetry collections, most recently Reading the Signs (The Cuba Press), and a novel, The Year of Falling. She lives in Wellington. http://janisfreegard.com

Bernadette Hall lives in the Hurunui, North Canterbury. She retired from high-school teaching in 2005 in order to embrace a writing life. This sonnet touches on the years 2006 and 2011 when she lived in Wellington, working at the IIML. Her friendship with the Wellington poet, Geoff Cochrane, is referenced in several of her poems. Another significant friendship, begun in 1971, was instrumental in turning her towards poetry. That was with the poet/painter, Joanna Margaret Paul. A major work that she commissioned from Joanna in 1982, will travel the country for the next two years as part of a major exhibition of the artist’s work.

Mohamed Hassan is an award-winning journalist and writer from Auckland and Cairo. He was the winner of the 2015 NZ National Poetry Slam, a TEDx fellow and recipient of the Gold Trophy at the 2017 New York Radio Awards. His poetry has been watched and shared widely online and taught in schools internationally. His 2020 poetry collection National Anthem was shortlisted for the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards (2021).

Richard Langston is a poet, television director, and writer. ‘Five O’Clock Shadows’ is his sixth book of poems. His previous books are Things Lay in Pieces (2012), The Trouble Lamp (2009), The Newspaper Poems (2007), Henry, Come See the Blue (2005), and Boy (2003). He also writes about NZ music and posts interviews with musicians on the Phantom Billstickers website.

Poet and artist Cilla McQueen has lived and worked in Murihiku for the last 25 years. Cilla’s most recent works are In a Slant Light; a poet’s memoir (2016) and

Poeta: selected and new poems (2018), both from Otago University Press.

Kiri Piahana-Wong is a poet and editor, and she is the publisher at Anahera Press. She lives in Auckland.

Vaughan Rapatahana (Te Ātiawa) commutes between homes in Hong Kong, Philippines, and Aotearoa New Zealand. He is widely published across several genre in both his main languages, te reo Māori and English and his work has been translated into Bahasa Malaysia, Italian, French, Mandarin, Romanian, Spanish. Additionally, he has lived and worked for several years in the Republic of Nauru, PR China, Brunei Darussalam, and the Middle East.

Helen Rickerby lives in a cliff-top tower in Aro Valley. She’s the author of four collections of poetry, most recently How to Live (Auckland University Press, 2019), which won the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the 2020 Ockham Book Awards. Since 2004 she has single-handedly run boutique publishing company Seraph Press, which mostly publishes poetry.

Marty Smith is writing a non-fiction book tracking the daily lives of trainers and track-work riders as they go about their work at the Hastings racecourse. She finds the same kindness and gentleness there among people who primarily work with animals. On the poem: Grandad was very kind and gentle; Grandma had a rep for being ‘a bit ropey’. He was so kind that when my uncle Edward, told not to touch the gun, cocked it and shot the family dog, Grandad never said a thing to my heartbroken little uncle, just put his arm around him and took him home.

Ten poems about clouds

Twelve poems about ice

Ten poems about dreaming

Eleven poems about the moon

Twelve poems about knitting

Ten poems about water

Twelve poems about faraway

Fourteen poems about walking

Twelve poems about food

poems about home

poems about edge

poems about breakfast

Poetry Shelf celebrates new books: A poem sampler from Ian Wedde’s The Little Ache — a German Notebook

The Little Ache — a German Notebook, Ian Wedde, Victoria University Press, 2021

From The Little Ache—a German notebook

2

Im Hochsummer besuchen die Bienen viele unterschiedliche Blüten

‘In high summer the bees seek many different flowers’

caught my eye on the jar of honey

in the organic shop around the corner

in Boxhagenerstrasse

but outside it was already getting dark

at 4.30 in the afternoon

and the warm bars were filling

with a buzz of patrons

dipping their lips

into fragrant brews

jostling each other in a kind of dance

I didn’t join

(I didn’t know how to

couldn’t ‘find my feet’)

but took home my jar of Buckweizenaroma

buckwheat/bookwise aroma

and sampled some on a slice

of Sonnenblumenbrot.

6

Von allem Leid, das diesen Bau erfüllt,

Ist unter Mauerwerk und Eisengittern

Ein hauchlebendig, ein geheimes Zittern.

‘From all the suffering that fills this building

there is under masonry and iron bars

a breath of life a secret tremor.’

In the Moabit Prison memorial

where Albrecht Haushofer’s words

incised in the back wall

already wear the weary patinas of time and weather

or more probably the perfunctory smears

of graffiti cleansing

I’m assailed by a nipping dog

whose owners apologise in terms I don’t quite understand

though the dog does

and retreats ahead of the half-hearted kick

I lack the words to say isn’t called for.

The horizon’s filled with gaunt cranes

resting from the work of tearing down or building up

the forgettable materiality of history

an exercise one might say

in removing that which was draughty

and replacing it with that which can be sealed.

Or as it may be

tearing down the sealed panopticon

but making space to train dogs in.

21

Oberbaumbrücke

is one of those contrapuntal German nouns

that should be simple but isn’t

unless you think

‘upper-tree-bridge’ is simple.

The long trailing tresses of the willows

have turned pale green

and are thrashing in the wind

on the Kreutzberg side

of die Oberbaumbrücke

over the storm-churned Spree.

They are the uneasy ghosts of spring.

Gritty gusts

blow rubbish along the embankment.

In a crappy nook

a graffitied child clenches a raised fist.

Yesterday at the Leipzig Book Fair

I listened to a fierce debate

about the situation in Ukraine

and later visited the Nikolaikirche

where Johann Sebastian Bach had played the organ.

One situation was loud with discord

the other’s efflatus a ghostly counterpoint.

On the train back to Berlin

I received a text from Donna

who’d been rocking our granddaughter Cara to sleep.

My bag from the Book Fair

had a paradoxical misquote from Ezra Pound on it:

‘Literatur ist Neues,

das neu bleibt.’

The train was speeding at 200 kilometres an hour

towards the place I’m calling home

because it’s haunted by ancestors who left slowly

but surely

thereby established the first term

of my contrapuntal neologism:

Endeanfang.

26

The vanity of art

(Milan Kundera) –

In spring

I return to the Moabit Prison Memorial

Haushofer’s words are still there

writ large on the back wall

they seem a little faded

but that could be the effect

of lucid sunshine

which elongates the speeding shadows

of dogs chasing Frisbees

and picks out

the filigreed patterns of trees

beginning to be crowned

with pale baldachins of leaves.

The girl panhandling on the footpath

at Warschauer Strasse station

has scrawled an unambiguous request

on the cardboard placard

her dog’s sleeping head

seems to be dreaming:

‘cash for beer and weed

and food for the dog’.

What the ghosts of Moabit are saying

I find harder to understand.

The memorial park’s stark absences

move me

and the minimal architectural features

seem respectful and not vaunting.

But the silence here

which the happy dogs

vociferous nesting birds

industriously rebuilding cranes

and agitated railway station

do not fill

that silence

crowds into a place in the mind

that scepticism can’t reach

where ghosts gather obliviously

without caring if I sense them

or if any of this exists.

27

Patriotismus, Nationalismus, Kosmopolitismus, Dekadenz

are the words repeated over and over

by the artist Hanne Darboven

whose great work in the Hamburger Bahnhof

museum of contemporary art

like the nearby Moabit Prison Memorial

reduces what she knew

to the minimal utterances

the obsessive reductions

the repetitions

that anticipate the ghosts of themselves

in the silence of the archive.

Ian Wedde

Ian Wedde was born in 1946. He has published sixteen collections of poetry, most recently Selected Poems (2017). He was New Zealand’s Poet Laureate in 2011 and shared the New Zealand Book Award for poetry in 1978. The Little Ache — a German Notebook was begun while he had the Creative New Zealand Berlin Writer’s Residency 2013/2014 and often notes research done during that time, especially into his German great-grandmother Maria Josephine Catharina née Reepen who became the ghost that haunts the story of the character Josephina in Wedde’s novel The Reed Warbler.

Victoria University page

Poetry Shelf Monday poem: Cilla McQueen’s ‘Festival Time’

Festival Time

Pearl-grey moiré silk

above a base-line of pewter,

high top notes cloudy gold.

Oyster Festival tomorrow,

the day the road is jammed with traffic,

the day Bluff is invaded by lovers;

thousands of salt-sweet mouthfuls

dredged from their seabed, shucked deftly,

swallowed alive by the roistering crowd.

Too many people – I’m staying home.

After this rain the paradise ducks will come

down to the green field patched with sky.

Cilla McQueen

Cilla McQueen lives and writes in the southern port of Bluff. A recipient

of multiple awards for her poetry, she eats oysters as often as possible. Cilla’s most recent works are In a Slant Light: a poet’s memoir (2016) and Poeta: selected and new poems (2018), both from Otago University Press.

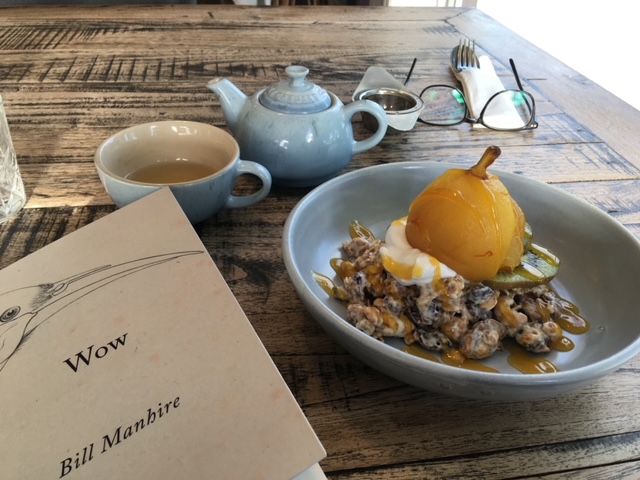

Poetry Shelf Theme Season: Eleven poems about breakfast

Breakfast is a lifelong ritual for me: the fruit, the cereal, the toast, the slowly-brewed tea, the short black. It is the reading, it is the silence, it is the companionship. It is finding the best breakfast when you are away at festivals or on tour, on holiday. This photograph was taken last year at Little Poms in Christchurch when I was at WORD. One of my favourite breakfast destinations. Breakfast is my gateway into the day ahead, it is food but it is more than food. It is the ideas simmering, the map unfolding, the poem making itself felt.

The poems I have selected are not so much about breakfast but have a breakfast presence that leads in multiple directions. Once again I am grateful to publishers and poets who are supporting my season of themes.

Unspoken, at breakfast

I dreamed last night that you were not you

but much younger, as young as our daughter

tuning out your instructions, her eyes not

looking at a thing around her, a fragrance

surrounding her probably from her

freshly washed hair, though

I like to think it is her dreams

still surrounding her

from her sleep. In my sleep last night

I dreamed you were much younger,

and I was younger too and had all the power –

I could say anything but needed to say

nothing, and you, lovely like our daughter,

worried you might be talking too much

about yourself. I stopped you

in my arms, pressed my face

up close to yours, whispered into

your ear, your curls

around my mouth, that you were

my favourite topic. That

was my dream, and that is still

my dream, that you were my favourite topic –

but in my dream you were

much younger, and you were not you.

Anna Jackson

from Pasture and Flock: New & Selected Poems, Auckland University Press, 2018

By Sunday

You refused the grapefruit

I carefully prepared

Serrated knife is best

less tearing, less waste

To sever the flesh from the sinew

the chambers where God grew this fruit

the home of the sun, that is

A delicate shimmer of sugar

and perfect grapefruit sized bowl

and you said, no, God, no

I deflated a little

and was surprised by that

What do we do when we serve?

Offer little things

as stand-ins for ourselves

All of us here

women standing to attention

knives and love in our hands

Therese Lloyd

From The Facts, Victoria University Press, 2018

How time walks

I woke up and smelled the sun mummy

my son

a pattern of paradise

casting shadows before breakfast

he’s fascinated by mini beasts

how black widows transport time

a red hourglass

under their bellies

how centipedes and worms

curl at prodding fingers

he’s ice fair

almost translucent

sometimes when he sleeps

I lock the windows

to secure him in this world

Serie Barford

from Entangled islands, Anahera Press, 2015

Woman at Breakfast

June 5, 2015

This yellow orange egg

full of goodness and

instructions.

Round end of the knife

against the yolk, the joy

which can only be known

as a kind of relief

for disappointed hopes and poached eggs

go hand in hand.

Clouds puff past the window

it takes a while to realise

they’re home made

our house is powered by steam

like the ferry that waits

by the rain-soaked wharf

I think I see the young Katherine Mansfield

boarding with her grandmother

with her duck-handled umbrella.

I am surprised to find

I am someone who cares

for the bygone days of the harbour.

The very best bread

is mostly holes

networks, archways and chambers

as most of us is empty space

around which our elements move

in their microscopic orbits.

Accepting all the sacrifices of the meal

the unmade feathers and the wild yeast

I think of you. Happy birthday.

Kate Camp

from The Internet of Things, Victoria University Press, 2017

How to live through this

We will make sure we get a good night’s sleep. We will eat a decent breakfast, probably involving eggs and bacon. We will make sure we drink enough water. We will go for a walk, preferably in the sunshine. We will gently inhale lungsful of air. We will try to not gulp in the lungsful of air. We will go to the sea. We will watch the waves. We will phone our mothers. We will phone our fathers. We will phone our friends. We will sit on the couch with our friends. We will hold hands with our friends while sitting on the couch. We will cry on the couch with our friends. We will watch movies without tension – comedies or concert movies – on the couch with our friends while holding hands and crying. We will think about running away and hiding. We will think about fighting, both metaphorically and actually. We will consider bricks. We will buy a sturdy padlock. We will lock the gate with the sturdy padlock, even though the gate isn’t really high enough. We will lock our doors. We will screen our calls. We will unlist our phone numbers. We will wait. We will make appointments with our doctors. We will make sure to eat our vegetables. We will read comforting books before bedtime. We will make sure our sheets are clean. We will make sure our room is aired. We will make plans. We will talk around it and talk through it and talk it out. We will try to be grateful. We will be grateful. We will make sure we get a good night’s sleep.

Helen Rickerby

from How to Live, Auckland University Press, 2019

Morning song

Your high bed held you like royalty.

I reached up and stroked your hair, you looked at me blearily,

forgetting for a moment to be angry.

By breakfast you’d remembered how we were all cruel

and the starry jacket I brought you was wrong.

Every room is painted the spectacular colour of your yelling.

I try and think of you as a puzzle

whose fat wooden pieces are every morning changed

and you must build again the irreproachable sun,

the sky, the glittering route of your day. How tired you are

and magnanimous. You tell me yes

you’d like new curtains because the old ones make you feel glim.

And those people can’t have been joking, because they seemed very solemn.

And what if I forget to sign you up for bike club.

The ways you’d break. The dizzy worlds wheeling on without you.

Maria McMillan

from The Ski Flier, Victoria University Press, 2017

14 August 2016

The day begins

early, fast broken

with paracetamol

ibuprofen, oxycodone,

a jug of iced water

too heavy to lift.

I want the toast and tea

a friend was given, but

it doesn’t come, so resort

to Apricot Delights

intended to sustain me

during yesterday’s labour.

Naked with a wad of something

wet between my legs, a token

gown draped across my stomach

and our son on my chest,

I admire him foraging

for sustenance and share

his brilliant hunger.

Kicking strong frog legs,

snuffling, maw wide and blunt,

nose swiping from side

to side, he senses the right

place to anchor himself and drives

forward with all the power

a minutes-old neck can possess,

as if the nipple and aureole were prey

about to escape, he catches his first

meal; the trap of his mouth closes,

sucks and we are both sated.

Amy Brown

from Neon Daze, Victoria University Press, 2019

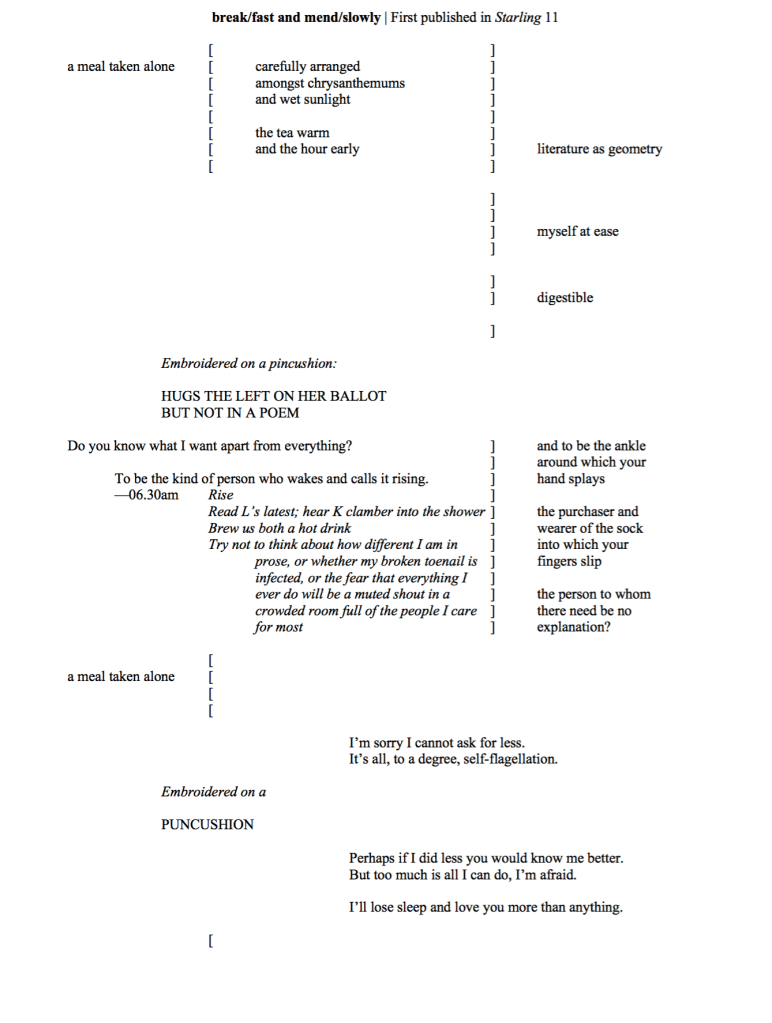

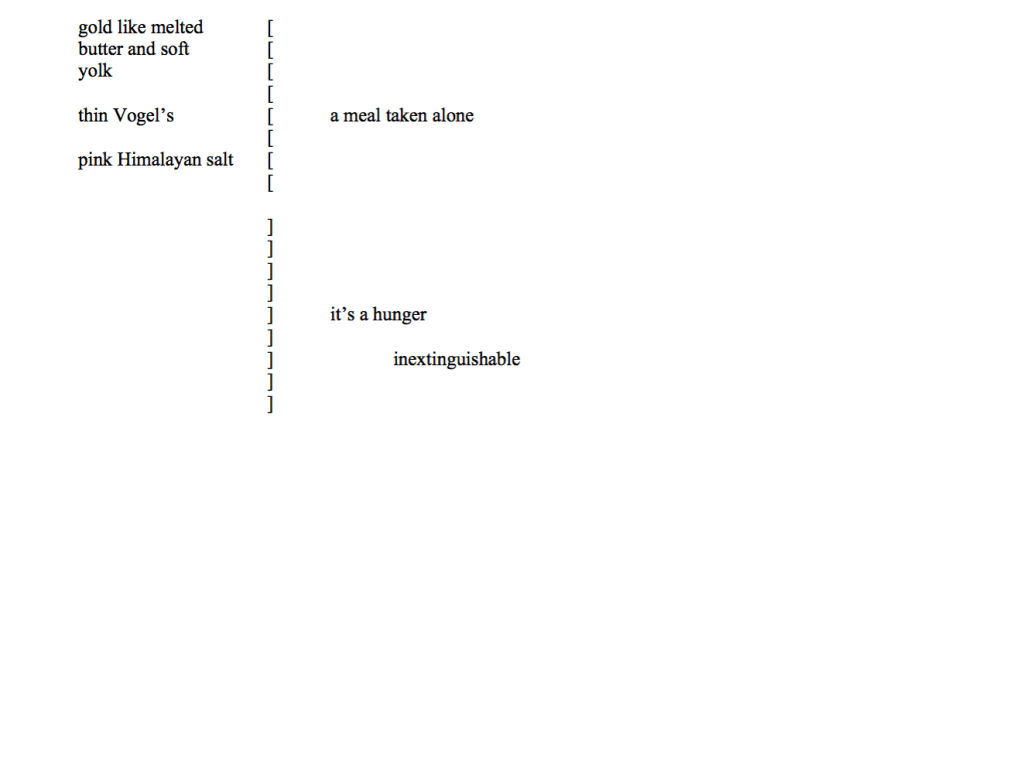

break/fast and mend/slowly

Tate Fountain

from Starling 11

I lay in our bed all morning

next to the half-glass of juice you brought me

to sweeten your leaving

ochre sediments settled in the liquid

a thin dusty film formed on the meniscus

but eventually I drank it

siphoning pulp through my teeth

like a baleen whale sifting krill from brine

for months after your departure I refused to look

at the moon

where it loomed in the sky outside

just some huge rude dinner plate you left unwashed

now ascendant

brilliant with bioluminescent mould

how dare you rhapsodize my loneliness into orbit

I laughed

enraged

to the thought of us

halfway across the planet staring up

at some self-same moon & pining for each other

but now I long for a fixed point between us

because from here

even the moon is different

a broken bowl

unlatched from its usual arc & butchered

by grievous rainbows

celestial ceramic irreparably splintered

as though thrown there

and all you have left me with is

this gift of white phosphorous

dissolving the body I knew you in

beyond apology

to lunar dust

Rebecca Hawkes

in New Poets 5, Auckland University Press, 2019, picked by Aimee-Jane Anderson-O’Connor

everything changing

I never meant to want you.

But somewhere

between

the laughter and the toast

the talking and the muffins

somewhere in our Tuesday mornings

together

I started falling for you.

Now I can’t go back

and I’m not sure if I want to.

Paula Harris

from woman, phenomenally

Breakfast in Shanghai

for a morning of coldest smog

A cup of black pǔ’ěr tea in my bedroom & two bāozi from the

lady at the bāozi shop who has red cheeks. I take off my gloves,

unpeel the square of thin paper from the bun’s round bottom.

I burn my fingers in the steam and breathe in.

for the morning after a downpour

Layers of silken tofu float in the shape of a lotus slowly

opening under swirls of soy sauce. Each mouthful of doufu

huā, literally tofu flower, slips down in one swallow. The

texture reminds me of last night’s rain: how it came down

fast and washed the city clean.

for homesickness

On the table, matching tiny blue ceramic pots of chilli oil,

vinegar and soy sauce. In front of me, the only thing that

warms: a plate of shuǐjiǎo filled with ginger, pork and cabbage.

I dip once in vinegar, twice in soy sauce and eat while the

woman rolls pieces of dough into small white moons that fit

inside her palm.

for a pink morning in late spring

I pierce skin with my knife and pull, splitting the fruit open.

I am addicted to the soft ripping sound of pink pomelo flesh

pulling away from its skin. I sit by the window and suck on the

rinds, then I cut into a fresh zongzi with scissors, opening the

lotus leaves to get at the sticky rice inside. Bright skins and leaves

sucked clean, my hands smelling tea-sweet. Something inside

me uncurling. A hunger that won’t go away.

NIna Mingya Powles

from Magnolia 木蘭, Seraph Press, 20020

Serie Barford was born in Aotearoa to a German-Samoan mother and a Palagi father. She was the recipient of a 2018 Pasifika Residency at the Michael King Writers’ Centre. Serie promoted her collections Tapa Talk and Entangled Islands at the 2019 International Arsenal Book Festival in Kiev. She collaborated with filmmaker Anna Marbrook to produce a short film, Te Ara Kanohi, for Going West 2021. Her latest poetry collection, Sleeping With Stones, will be launched during Matariki 2021.

Amy Brown is a writer and teacher from Hawkes Bay. She has taught Creative Writing at the University of Melbourne (where she gained her PhD), and Literature and Philosophy at the Mac.Robertson Girls’ High School. She has also published a series of four children’s novels, and three poetry collections. Her latest book, Neon Daze, a verse journal of early motherhood, was included in The Saturday Paper‘s Best Books of 2019. She is currently taking leave from teaching to write a novel.

Kate Camp’s most recent book is How to Be Happy Though Human: New and Selected Poems published by VUP in New Zealand, and House of Anansi Press in Canada.

Tate Fountain is a writer, performer, and academic based in Tāmaki Makaurau. She has recently been published in Stuff, Starling, and the Agenda, and her short fiction was highly commended in the Sunday Star-Times Short Story Competition (2020).

Paula Harris lives in Palmerston North, where she writes and sleeps in a lot, because that’s what depression makes you do. She won the 2018 Janet B. McCabe Poetry Prize and the 2017 Lilian Ida Smith Award. Her writing has been published in various journals, including The Sun, Hobart, Passages North, New Ohio Review and Aotearotica. She is extremely fond of dark chocolate, shoes and hoarding fabric. website: http://www.paulaharris.co.nz | Twitter: @paulaoffkilter | Instagram: @paulaharris_poet | Facebook: @paulaharrispoet

Rebecca Hawkes works, writes, and walks around in Wellington. This poem features some breakfast but mostly her wife (the moon), and was inspired by Alex Garland’s film adaptation of Jeff Vandermeer’s novel Annihilation. You can find it, among others, in her chapbook-length collection Softcore coldsores in AUP New Poets 5. Rebecca is a co-editor for Sweet Mammalian and a forthcoming collection of poetry on climate change, prances about with the Show Ponies, and otherwise maintains a vanity shrine at rebeccahawkesart.com

Anna Jackson lectures at Te Herenga Waka/Victoria University of Wellington, lives in Island Bay, edits AUP New Poets and has published seven collections of poetry, most recently Pasture and Flock: New and Selected Poems (AUP 2018).

Therese Lloyd is the author of two full-length poetry collections, Other Animals (VUP, 2013) and The Facts (VUP, 2018). In 2017 she completed a doctorate at Victoria University focusing on ekphrasis – poetry about or inspired by visual art. In 2018 she was the University of Waikato Writer in Residence and more recently she has been working (slowly) on an anthology of ekphrastic poetry in Aotearoa New Zealand, with funding by CNZ.

Maria McMillan is a poet who lives on the Kāpit Coast, originally from Ōtautahi, with mostly Scottish and English ancestors who settled in and around Ōtepoti and Murihiku. Her books are The Rope Walk (Seraph Press), Tree Space and The Ski Flier (both VUP) ‘Morning song‘ takes its title from Plath.

Nina Mingya Powles is a poet and zinemaker from Wellington, currently living in London. She is the author of Magnolia 木蘭, a finalist in the Ockham Book Awards, a food memoir, Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai, and several poetry chapbooks and zines. Her debut essay collection, Small Bodies of Water, will be published in September 2021.

Helen Rickerby lives in a cliff-top tower in Aro Valley. She’s the author of four collections of poetry, most recently How to Live (Auckland University Press, 2019), which won the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the 2020 Ockham Book Awards. Since 2004 she has single-handedly run boutique publishing company Seraph Press, which mostly publishes poetry.

Poetry Shelf review: Iona Winter’s gaps in the light

gaps in the light, Iona Winter, Ad Hoc Fiction, 2021

‘Gaps in the Light uses form in innovative ways to express deeply the experience of loss and joy in ways I can’t remember reading anywhere else. Nothing is binary here – everything feels multidimensional, so perfectly complicated, like echoes off multiple surfaces. It’s simply astounding!’

Pip Adam, author of Nothing to See, The New Animals, I’m Working on a Building, and Everything We Hoped For

Iona Winter, Waitaha/Kāi Tahu, lives on the East Otago Coast. She holds a Masters in Creative Writing and has published two previous collections, Te Hau Kaika (2019) and then the wind came (2018). Iona’s latest work gaps in the light comes with ‘advance praise’, tributes from other writers that include Helen Lehndorf, Kirstie McKinnon and Pip Adam. I so loved this suite of endorsements I have shared an extract from Pip Adam’s comments above. If I had read these words browsing in a bookshop, I would have bought the book, resisted all chores and distractions, and started reading. I too adore this book , and like Pip, know of no other quite like it. The slow-building embrace of loss and joy sets up long-term residency as you read.

The collection is dedicated to Iona’s son Reuben (20.5.1994 – 17.9.2020), and the dedication page becomes a pause a prayer a bouquet of sadness before you turn the page. I stalled here. I waited at this border between life and death. And then I entered a peopled glade: characters voices circumstances. Iona lays her own pain and loss beneath the surface of every scene, the hybrid writing stretching delving recovering above the subterranean ache. Writing becomes preservation, connection, ebb and flow, fighting against and fighting for. It is writing as lament and it is writing as meditation.

I dwell on the phrase ‘Streams of consciousness like gaps in the light’. What does it mean, but more importantly what does it feel? The writing is leaning in and listening to the dark without letting go of the framing light. A little like the mother and daughter in ‘Swallows’:

When we go walking, I tell our daughter what it means when the raupō are bent and spiders have crafted cocoons — white flags signalling peace. We inhale autumnal pine needle paths that smell of Christmas too early.

Little deceptions we tell one another make the intolerable less so.

When on the beach a heart stone is picked up, just one from the cluster, to hold and to carry. The sentence is smooth like the heart stone, but a few lines later the sound shifts and hits your ear sharply: ‘When mildew and salt scratched at my insides, and my back hit the stippled deck — life met decay once again.’ You will move from terminal illness to birdsong, from what you do to keep going to what you see out the window. There is a muscular thread of grandmother and grandfather wisdom. There is the way you get thrown off balance, expectedly, unexpectedly. The recurring thoughts of a loved one, the sight of the moon that startles: ‘it throws me off balance / that look of yours / an unexpected full moon in daylight showing herself on the horizon’ (from ‘Whorls’).

Iona is translating personal experience into hybrid writing and it is incredibly potent. I can’t imagine how hard this book was to write, but it is a gift, a glorious taonga, a gift of aroha. Thank you, Iona, thank you.

I prefer to expose the greying strands of my hair.

I prefer kōrero in person as opposed to communicating

via the Internet.

I prefer to sing aloud in the car.

I don’t prefer silent unspoken things.

I prefer non-martyred compromise.

I prefer to tend my wounds before creating them for

another.

I prefer compassion to witch-hunts.

I prefer to believe in the possibility of something

beautiful, rather than fear the inevitable pain of loss.

I prefer to choose aroha.

from ‘Natives’

Ad Hoc page

Iona Winter page

Poetry Shelf: Iona reads ‘Gregorian’

Poetry Shelf celebrates Landfall 241

Landfall 241, edited by Emma Neale, reviews editor Michelle Elvy

Otago University Press, 2021

As Landfall 241 is the final issue edited by Emma Neale, Poetry Shelf takes a moment to toast the stellar work she has done as editor over the past few years. Like the other Landfalls under her watch, the latest issue is a vital compendium of poetry, fiction, reviews, essays and artwork. I am delighted to see a range of familiar and unfamiliar voices, emerging poets and those established, and to traverse wide-ranging subject matter and styles. The winners of the Charles Brasch Young Writers’ Essay Competition are announced and the artwork is sublime, distinctive, eye-catching.

Bridget Reweti’s stereoscopic photographs invert Allen Curnow’s ‘Unknown Seas’ to become ‘Known Seas’. If you hold the double images at the right distance and look though to the horizon you get a sense of spatial depth. It got me considering how I ‘hold’ a poem and experience multiple shifting depths. The way a poem pulls you into space in myriad ways. The way you float through layers, in focus out of focus, absorbing the physical, the intangible, the felt.

I made a long list of poems that held my attention as I read. Alison Glenny’s extract from ‘Small Plates’ haunted me with its off-real tilts:

The poets move together in flocks. One finds a new song and the others take it up. Developers move in and the poets rise together to find a new perch. The night is a forest with missing eaves. So much wood to build boxes for poems to live in. Each leaf a quarrel over the exact placement of the moon.

In the end I assembled a Landfall reading comprising voices I have rarely managed to hear, if ever, at events. It is so very pleasing to curate a reading from my rural kitchen and feel myself drawn to effervescent horizons as I listen. The print copy is equally rewarding!

The poets in Landfall 241: Joanna Aitchison, Philip Armstrong, Rebecca Ball, David Beach, Peter Belton, Diana Bridge, Owen Bullock, Stephanie Burt, Cadence Chung, Ruth Corkill, Mary Cresswell, Alison Denham, Ben Egerton, Alison Glenny, Jordan Hamel, Trisha Hanifin, Michael Harlow, Chris Holdaway, Lily Holloway, Claudia Jardine, Erik Kennedy, Brent Kininmont, Wen-Juenn Lee, Wes Lee, Bill Manhire, Talia Marshall, Ria Masae, James McNaughton, Claire Orchard, Joanna Preston, Chris Price, Tim Saunders, Rowan Taigel, Joy Tong, Tom Weston

Landfall page here

The readings

Talia Marshall reads ‘Learning How to Behave’

Cadence Chung reads ‘that’s why they call me missus fahrenheit’

Claudia Jardine reads ‘Field Notes on Elegy’

Ria Masae reads ‘Papālagi’

Stephanie Burt reads ‘Kite Day, New Brighton’

Tim Saunders reads ‘Devoir’

Jordan Hamel reads ‘Society does a collective impersonation of Robin Williams telling Matt Damon “It’s not your fault” repeatedly in Good Will Hunting‘

Rowan Taigel reads ‘Mothers & Fathers’

Trisha Hanifin reads ‘Without the Scaffold of Words’

The Poets

Stephanie Burt is a professor of English at Harvard and has also taught at the University of Canterbury. Her most recent books include Callimachus (Princeton University Press, 2020) and Don’t Read Poetry: A book about how to read poems (Basic, 2019).

Cadence Chung is a student at Wellington High School. She first started writing poetry during a particularly boring Maths lesson when she was nine, and hasn’t stopped since. She enjoys antique stores, classic literature, and tries her best to be an Edwardian dandy.

Jordan Hamel is a Pōneke-based writer, poet and performer. He was the 2018 New Zealand Poetry Slam champion and represented NZ at the World Poetry Slam Champs in the US in 2019. He is the co-editor of Stasis Journal and co-editor of a forthcoming NZ Climate Change Poetry Anthology from Auckland University Press. He is a 2021 Michael King Writer-in-Residence and has words published in The Spinoff, Newsroom, Poetry New Zealand, Sport, Turbine, Landfall, and elsewhere.

Trisha Hanifin has a MA in Creative Writing from AUT. Her work has been published in various journals and anthologies including Bonsai: Best small stories from Aotearoa New Zealand (Canterbury University Press, 2018). In 2018 she was runner up in the Divine Muses Emerging Poets competition. Her novel, The Time Lizard’s Archeologist, is forthcoming with Cloud Ink Press.

Claudia Jardine (she/her) is a poet and musician based in Ōtautahi/Christchurch. In 2020 she published her first chapbook, The Temple of Your Girl, with Auckland University Press in AUP New Poets 7 alongside Rhys Feeney and Ria Masae. For the winter of 2021 Jardine will be one of the Arts Four Creative Residents in The Arts Centre Te Matatiki Toi Ora, where she will be working on a collection of poems.

Talia Marshall (Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Rārua, Rangitāne ō Wairau, Ngāti Takihiku) is currently working on a creative non-fiction book which ranges from Ans Westra, the taniwha Kaikaiawaro to the musket wars. This project is an extension of her 2020 Emerging Māori Writers Residency at the IIML. Her poems from Sport and Landfall can be found on the Best New Zealand Poems website.

Ria Masae is a writer, spoken word poet, and librarian of Samoan descent, born and raised in Tāmaki Makaurau. Her work has been published in literary outlets such as, Landfall, takahē, Circulo de Poesia, and Best New Zealand Poems 2017 and 2018. A collection of her poetry is published in, AUP New Poets 7.

Tim Saunders farms sheep and beef near Palmerston North. He has had poetry and short stories published in Turbine|Kapohau, takahē, Landfall, Poetry NZ Yearbook, Flash Frontier, and won the 2018 Mindfood Magazine Short Story Competition. He placed third in the 2019 and 2020 National Flash Fiction Day Awards, and was shortlisted for the 2021 Commonwealth Short Story Prize. His first book, This Farming Life, was published by Allen & Unwin in August, 2020.

Rowan Taigel is a Nelson based poet and teacher. Her poetry has been published in Landfall, Takahe Journal, Shot Glass Journal, Aotearotica, Catalyst, After the Cyclone (NZPS Anthology, 2017), Building a Time Machine (NZPS Anthology, 2012), and she has been a featured poet in A Fine Line, (NZPS). Rowan received a Highly Commended award for the 2020 Caselberg International Poetry Competition with her poem ‘Catch and Kiss’. She can often be found in local cafes on the weekend reading and writing poetry over a good coffee.

Poetry Shelf write-ups: Jordan Hamel on Lōemis Epilogue

Lōemis Epilogue

Poetry and music go together like candles and churches, and what’s better than poetry and music? Poetry and music in the cavernous St Peters church on a stormy night. Lōemis Festival’s recent event Epilogue, born out of the mind of Festival Artistic Director Andrew Laking, brought together some of the city’s finest ensemble musicians and a murderer’s row of local poets for an evening of original composition that was at times ecstatic, somber, thought-provoking, soothing and so much more. Local wordsmiths Nick Ascroft, Chris Tse, Rebecca Hawkes, Ruby Solly and Harry Ricketts were all given the opportunity to write and deliver original poems in this reimagined requiem mass and their words the space and scope they deserved.

The event page promised an echo of the original idea, that follows the same rise, fall and atmosphere, and it delivered, interspersing music and the spoken word. The event begun with a composition from the ensemble and they punctuated every poet’s performance, creating room for breach and reflection and time for the poems to wash over the crowd and reset the mood for the next poet. The church was dark and moody and still throughout, while this made for the perfect audience experience it made it impossible to take any notes during the show, as a result I’m just going to gush about all the wonderful performers who took the stage.

Nick Ascroft was the first poet to take to the pulpit. He delivered two new poems that were personal and inventive, hilarious and heartbreaking. While I’ve been a fan of Nick’s wit on the page for years it was great to have the opportunity to see him read in this context, not only did his poems set the tone for the evening but his opener ‘You Will Find Me Much Changed’ has been lounging about in my head ever since. Next up was everyone’s favourite poet crush Chris Tse. Dressed in dapper attire apparently inspired by a fancy can of water, Chris, much like Nick used repetition to build his sermon, like a mantra, an incantation. It reverberated off the stained-glass windows and when Chris finished with his piece, entitled ‘Persistence is futile’, I got so upset I have to wait until 2022 for his third collection.

Rebecca Hawkes was next, accidentally dressed as Kath from Kath and Kim due to a wardrobe malfunction but it didn’t matter. Rebecca is the type of poet tailor-made for an event like this, she can conjure imagery that spans the grotesque to the sublime and she has a performance style that colours those images so vividly you feel fully submerged in her world. Speaking of complex other worlds, Ruby Solly is one of the masters of weaving them together and that was on full display in her performance. Ruby also played taonga pūoro with the ensemble before her reading just to remind the audience how talented she is. The last poet of the evening was Harry Ricketts, whose Selected Poems is out in the world right now. Harry’s ‘The Song Sings the News of the World’ closed out the evening, and while it wasn’t necessarily the most complex or challenging poem of the evening, it was the perfect ending, prompting all those watching to look forward and wonder, leaving the audience with a sense of hope.

Overall it was the perfect evening, poetry and music together as they should be, in a venue built for ritual. Epilogue is the type of event that showcases what poetry can be when it’s not confined, stretching it and moulding it into something unexpected, the type of event Andrew and his VERB co-director Clare Mabey excel at producing. I sincerely hope Epilogue doesn’t live up to its namesake and we get to see it again in one form or another.

Jordan Hamel

Music by Nigel Collins and Andrew Laking, in collaboration with Simon Christie and Maaike Beekman. New texts written and read by Chris Tse, Rebecca Hawkes, Harry Ricketts, Ruby Solly, and Nick Ascroft. With Dan Yeabsley (reeds), Tristan Carter (violin), and Dayle Jellyman (keys).

Jordan Hamel is a Pōneke-based writer, poet and performer. He was the 2018 New Zealand Poetry Slam champion and represented NZ at the World Poetry Slam Champs in the US in 2019. He is the co-editor of Stasis Journal and co-editor of a forthcoming NZ Climate Change Poetry Anthology from Auckland University Press. He is a 2021 Michael King Writer-in-Residence and has words published in The Spinoff, Newsroom, Poetry New Zealand, Sport, Turbine, Landfall, and elsewhere.

Jordan Hamel’s poem ‘You’re not a has-been, you’re a never was!’