It’s a week when I feel on edge about everything: the news a back slap of global and local misdeeds, COVID spread, Hong Kong oppression, petty political point scoring, exploiting the system for the good of the individual rather than the good of the whole, the maltreatment of children in care, my internet and landline going down amplifying my aloneness, the strength of the bubble, the weakness of the border, the need to acknowledge how well our Government has done when you keep things in perspective, the fact I haven’t planted the boadbean seeds yet, the fact I am not getting enough sleep, the night-time nag the future is uncertain. And yet I make a pot of leek, cauliflower and corn soup with harissa, and I am reading the edges in Iona Winter’s wonderful gaps in the light, and somehow, in some remarkable miraculous way, I feel joy. Posting poems with some kind of edge feels entirely fitting.

The poems

Thresh/hold

It looked inviting

that blue promise

so I stepped through

but the door unframed

my thought, unhinged

my indoor-outdoor flow.

Now all’s astray, I don’t

know why I came or where

to go. I am misplaced,

a left-hand mitten dropped

on concrete, getting

wet, that splits the sense

of keeping warm right

down the middle. I’m

hot and cold, I’m black

and blue, my fine boot on

the other foot but on this one

somebody else’s shoe.

Chris Price

from Beside Herself Auckland University Press, 2016, suggested by Amy Brown

The poem that is like a city

This poem is like a city. It is full of words.

Doing words. And being words. And words

that compare one thing to another thing

and words that hold everything together.

This poem has a high rise at its centre

with a view across the plains to the hills.

It has a CBD and CEOs and a thousand

acronyms whirring like wheels, This

poem is going places. It also has small

prepositions where people pause, drink

coffee and read the paper. They go to

and from and sit before and behind.

They walk across the park. Crunching

like gerunds on white gravel while

watching dogs splashing. Ducks quack

and rise. Like inflections? At the end of

phrases? The way we do here? This

poem is a crowded street where words

clatter in several languages and every

thing you see or touch has many names.

This poem is written in the gold leaf of

faith and in the red capitals of SALE

and BUY NOW and all the people walk

among the words as if they were trees

and ornament and would never fall off

the edges of their white page,

This poem jolts at the caesura and all

the words slide sideways, slip from

the beam in dusty slabs, The children

who were learning how to say hello

tap goodbye goodbye in all their

voices , reaching in the dark for the

mother tongue. There is no word in

English for this. No word in any city.

This poem is palimpsest, scraped

clean each morning and dumped

in the harbour. But at night it rises.

The moon buttons back the dark on

towerblock, mall and steeple. Cars

boom hollow on a phantom avenue,

cups fill with froth and nothing and

an empty bus wheezes up Colombo

Street. Stops for the children who

perch waiting like similes for

chatter and flight, tapping their

abbreviations.

Ths pm is lk

a brkn cty

all its wds r

smshd to

syllbyls.

Each syllbl

a brck.

Fiona Farrell

from The Broken Book Auckland University Press, 2011

On discovering your oncologist is a travel agent

There is a choice, he says. The shorter route, without add-ons,

the ‘no frills’, no-treatment way would be faster, more direct.

You’d arrive at your destination ahead of time, having avoided the

pitfalls of travelling: no missed connections, lost luggage or jet lag.

The longer route would provide a wider panorama, more stopovers,

new experiences. You’d wear an ID tag on your wrist. There would be

regular appointments, hours spent in waiting rooms scrutinizing food

and fashion magazines, art on walls. There would be needles, tubes

and drains, a slow-playing drama with a diverse cast of characters

constantly checking your name and number, oxygen levels, pulse,

temperature, blood pressure. There would be drugs and delirium;

you would cross time zones, travel in all weathers, meet strangers,

make new friends, embrace old ones. You would need time

and fortitude. You have to decide, now, so that plans can be set

in place. There’s no map for the journey, no certainty about what lies

ahead. No clear directions. No estimated time of arrival.

The ground you stand on is shaky, the horizon hazy, both routes

daunting from a distance. One thing is certain. There’s no going

back. That’s not an option. Your name is on the passenger list.

You must pack your own bags and choose which way you will go.

Elizabeth Brooke-Carr

from Wanting to Tell You Everything Caselburg Press, 2020

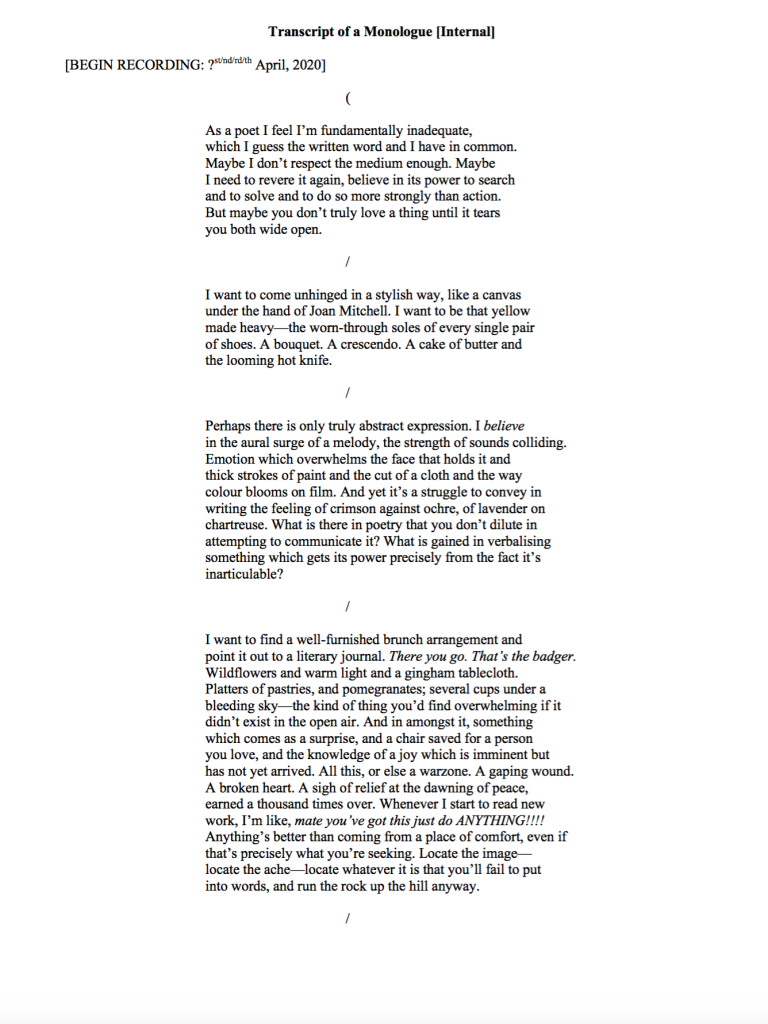

Transcript of a Monologue [Internal]

Tate Fountain

Seams

In time all cities blur and connect

as each street remembers

another, remembers the downward

pressure on your temple

as the plane rises, rises, as the lights

of one city are gurgled by fog, and what’s left

is one more night between time zones.

What glow here. What unbreakable seams.

You know the earth, like your body, can’t take this,

won’t last, and yet tonight you need too much to get home.

What else do you need too much?

Another plane slips across darkness before the cloud shifts and again

a city—its networked wide grids, grips of colour, unreal green

of some outskirts’ stadium before that black cloud pours back in.

Did you use your time on earth to save

what you wanted? Did you use anyone

the way you should? What song

will you sing as the light leaves,

as the mask’s lowered over your eyes?

Alice Miller

This poem first appeared in The Poetry Review and also the collection, What Fire (Pavilion, 2021).

The Tape

–for Chris Mead–

Tonight big squalls

lift off the sea channel

below the dark cliff

at the end of our section.

Pine branches thrash

against the garage,

television aerials rattle

on the neighbour’s rooftop.

My parents snore

in their room upstairs.

Under the bedcovers,

I put the C-60 tape,

handed to me by Matt Klee

at Engineering class,

into my blue Walkman.

When I hit the Play button,

spools click and spin.

There’s feedback,

distortion in reverse,

the blistering wail of a Stratocaster;

the louche yet gentle voice

of a prophet.

I sat bolt upright–

it’s as if god has spoken

to me directly.

And this is the first time

I feel the power

of language as poetry.

Michael Steven

from Walking to Jutland Street Otago University Press, 2018

Edgeland

Awks: you winged Auk-thing, awkward, huddling;

you wraparound, myriad, amphibious,

stretchy, try-hard, Polywoodish

juggernaut; you futurescape, insectivorous,

Akarana, Aukalani, Jafaville, O for Awesome,

still with the land-fever of a frontier town —

your surveyors who tick location, location, location,

your land-sharks, your swamp-lawyers, your merchant kings,

your real estate agents who bush-bash for true north,

your architecture that fell off the back of a truck,

your shoebox storerooms of apartment blocks,

your subdivisions sticky as pick and mix lollies;

you fat-bellied hybrid with your anorexic anxieties,

your hyperbole and bulimia, your tear-down and throw-up,

the sands of your hour-glass always replenished,

your self-harm always rejuvenated, unstoppable;

you binge-drinker, pre-loader, storm-chaser,

mana-muncher, hui-hopper, waka-jumper,

light opera queen, the nation’s greatest carnivore;

cloud-city of the South Pacific, it’s you the lights adore.

David Eggleton

from Edgeland, Otago University Press, 2018, chosen by Jenny Powell

Precarious

the first time I listened to Jupiter sound waves on the internet

I saw myself from a great distance as

a solitary beam of light flaring

in a dark suburban street

the other residences curtained and sombre

in this aching utopia

that is not paradise –

someone I know says their recurring nightmare

is of waking up to find a huge new planet

in the sky

nearly close enough to touch:

as a spinning ball in so much unconquerable dark

the Earth is ridiculously easy to finish off

Anuja Metra

from Starling, Issue 2.

It’s worth almost anything

That feeling right before everything bursts

Sitting on the bench in Cathedral Park

The one down the path from the tree we used to pile in

Hang loud like different primates

Bottles loose, lips curved almost grimace

If not for the laugh of our throats stretched wide

We’re a spectacle

A performance

We’re so goddamn tantalizing

Anyone would twist themselves into knots to get to us and they do

Guess it’s all that big trans energy Sam was talking about

Sam always knows what she’s talking about cause she’s a witch

Who looks like a car painted with cartoon flames

Super powerful, you know?

You’re playing dead on the bench

You’re playing dead cause you want to die

But also cause you want to kiss me

You want me to lean my face close to your face

In jest to check if you’re breathing

You want me to pause two beats too long

That’s when you’ll open your eyes

And we’ll look at each other right before

The scene cuts

Sitting on the couch at my parent’s house

Just ~vibrating~ the air

watching Wild Things

For the plot, you know

You’re Neve Campbell, obviously

I’m Denise Richards and when all of this is over

Neither of us will be women

Speaking of things we’re afraid to admit . . .

How about my entire adolescence, hmm??

Bottle stoppered too afraid to drink

The litany of dropped glances and

Unsatisfied thoughts-

You dipped out before it finished

Cause well, cause you know why

I’m sticking it out for the memories only

Cause when you left you were everywhere

But I’m scared if I go too there’ll be no one

To remember all the stupid bullshit

That happened just to you and me

Was it gulab jamun in your Wellington depression flat?

Was it hands pressed hard into fully clothed thighs?

Sneaking off to smoke weed at my sister’s wedding

She was always so mad we were better friends

But it wasn’t that, we were in love

Wanted to fuck but didn’t know how

Didn’t know we were allowed to do anything else

But press real close to the edge of the bubble

Waiting to see if it would pop

Eliana Gray

Trip with Mum

Mum is at Disneyland again—she goes regularly these days,

favouring evenings it might storm. This is the first time she’s

brought me along, and I’m the memory of my ten-year-old self,

looking for the roller coaster, stopping Snow White to ask the

way. But Mum insists we work our way up from the carousel,

facing each level of fear as we progress. I’m on the upward swoop

of a pink and gold pony with sequinned reins when Mum says,

I’m worried you’re addicted to drugs. I stagger as I dismount, and

Mum looks suspicious, but leads us expertly to the cup and saucer

ride, winking at the guard and bypassing the line. Everyone has

pain, she says, gripping the bar that’s keeping us in. The veins and

sunspots on her hands pop like fortune’s marks. It’s easy to forget

she’s getting old too. It’s difficult to keep looking at her—I’m

concentrating on keeping my stomach inside my body, and my

lunch inside of that. This is like the year of bad tampon ads when

I was twelve or thirteen, and we still watched TV as a family—

just don’t move and it’ll stop soon … If I let go of the bar now

I would whoosh out of here so far and fast that I would go

into orbit. Mum might look for me at dusk from the porch back

home, and watch me get smaller and smaller and brighter and

brighter as my outer layers burned off. I would see her there and

be unable to wave, my arms pressed to my sides by the speed. I’d

try shouting things like, What do you know about pain?! and, I’m

afraid! and finally, I love you! as I grew smaller and smaller and she

grew older and older and everything just kept spinning.

Hannah Mettner

from Fully Clothed and So Forgetful Victoria University Press, 2017

Outcast

for Audre

I’m a darling in the margins

but you said

be nobody’s darling / be an outcast

take the contradictions of your life

and wrap around / you like a shawl

to parry the stones / keep you warm

I keep what you said

pinned by brass tacks

against every wall ‘cos

I’m a darling by nature

traitor to the rebel

show me a mould

I’ll fill it, an unmade bed

I’ve already made it

draw me a paper road I’ll sign it

over to whoever says

they need it diverted for a better cause

but you said

be nobody’s darling

and that which casts me out

is cast about me

that which warms my flesh

guards my bones

and when I found

it to be true

the part about freedom

your shawl

became a fall of Huka curls

plunging black through suburban streets

a grey beach cottage firing

paua spirals under its eaves

his hand pressing want under

the wake table

a cocooning quilt pulled back under

the slim promise of sun

a brown woman walking

genealogy swimming her calves

a green dress worn on a blue blue day

because she can

it’s become a map

to get us beyond the line

the justified edge

that breaking page

it’s become a map in my arms

to get us beyond the reef

Selina Tusitala Marsh

from fast talking PI Auckland University Press, 2009

The poets

Elizabeth Brooke-Carr (1940 – 2019) was a Dunedin poet, essayist, short story writer, teacher and counsellor. Her writing appeared in newspapers, online journals and anthologies. She was awarded the New Zealand Society of Authors’ 75th Anniversary Competition and the Dunedin Public Libraries competition Changing Minds: Memories Lost and Found. She received a PhD from the University of Otago.

David Eggleton is the Aotearoa New Zealand Poet Laureate 2019 – 2022. His most recent book is The Wilder Years: Selected Poems, published by Otago University Press.

Fiona Farrell publishes poetry, fiction, drama and non-fiction. In 2007 she received the Prime Minister’s Award for Fiction, and in 2012 she was appointed an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for Services to Literature. Her most recent publication, Nouns, verbs, etc. Selected Poems (OUP 2020) has been warmly reviewed as ‘a Poetry Treasure House…a glorious book’ (Paula Green, Poetry Shelf), and ‘an excellent retrospective…remarkable for drawing small personal realities together with the broad sweep of history.” (Nicholas Reid, The Listener). After many years in remote Otanerito bay on Banks Peninsula, she now lives in Dunedin.

Eliana Gray is a poet, youth worker and arts facillitator. They like queer subtext, collaborative writing and making sure people have a nice time. They have had words in: SPORT, Landfall, Poetry NZ, Mayhem, and others. Their debut collection, Eager to Break, was published by Girls On Key Press in 2019, and in 2020 they undertook residencies in both Finland and Ōtepoti.

Tate Fountain is a writer, performer, and academic based in Tāmaki Makaurau. She has recently been published in Stuff, Starling, and the Agenda, and her short fiction was highly commended in the Sunday Star-Times Short Story Competition (2020).

Selina Tusitala Marsh (ONZM, FRSNZ) is the former New Zealand Poet Laureate and has performed poetry for primary schoolers and presidents (Obama), queers and Queens (HRH Elizabeth II). She has published three critically acclaimed collections of poetry, Fast Talking PI (2009), Dark Sparring (2013), Tightrope (2017) and an award-winning graphic memoir, Mophead (Auckland University Press, 2019) followed by Mophead TU (2020), dubbed as ‘colonialism 101 for kids’.

Hannah Mettner (she/her) is a Wellington writer who still calls Tairāwhiti home. Her first collection of poetry, Fully Clothed and So Forgetful, was published by Victoria University Press in 2017, and won the Jessie Mackay Award for best first book of poetry at the 2018 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. She is one of the founding editors of the online journal Sweet Mammalian, with Sugar Magnolia Wilson and Morgan Bach.

Alice Miller’s third poetry collection, What Fire, came out in May 2021 from Pavilion. She is also the author of the novel More Miracle than Bird (Tin House, 2020). She lives in Berlin.

Anuja Mitra lives in Auckland. Her writing has appeared in Takahe, Mayhem, Cordite Poetry Review, Starling, Sweet Mammalian, Poetry Shelf and The Three Lamps, and will appear in the AUP anthology A Clear Dawn: New Asian Voices from Aotearoa New Zealand. She has also written theatre and poetry reviews for Tearaway, Theatre Scenes, Minarets and the New Zealand Poetry Society. She is co-founder of the online arts magazine Oscen.

‘Thresh/hold’ was first published in Chris Price’s Beside Herself (Auckland University Press, 2016). Her next book, an essay in collaboration with photographer Bruce Foster, is forthcoming in Massey University Press’s kōrero series of ‘picture books for adults’ later this year.

Michael Steven is an Auckland poet. His current research interests include microbes and organic gardening – growing food and rongoā using no-till and KNF farming methods. Recent writing appears in Kete, Photoforum, Poetry New Zealand Yearbook 2021, and Õrongohau|Best New Zealand Poems 2020.

Pingback: Poetry Shelf Theme Season: Twelve poems about kindness | NZ Poetry Shelf

Pingback: Paula Green’s Poetry Themes – Janis Freegard's Weblog

Pingback: Poetry Shelf Theme Season: Thirteen poems about light | NZ Poetry Shelf

Pingback: Poetry Shelf Theme Season: Thirteen poems about song | NZ Poetry Shelf

Pingback: Poetry Shelf Theme Season: Sixteen poems of land | NZ Poetry Shelf

Pingback: Poetry Shelf Theme Season: Eighteen poems about love | NZ Poetry Shelf