Today is International Women’s Day. At breakfast, I read NZ Supreme Court Judge Susan Glazebrook’s terrific story about her ongoing ZOOM efforts to help get women Judges out of Afghanistan last year (with the help the International Association of Women Judges). The story is in the February issue of North & South and it is unmissable. It feels like we are living and breathing under such a blanket of darkness at the moment. We know the list: the pandemic and its ripple effects, misguided protests, impending war, human suffering under despots across the globe, misguided journalism, mis-and-disinformation, poverty, greed. At times it is too much. I switch off social media, the radio, the papers to avoid toxic voices creeping in with their destructive influences influencing the vulnerable and the disenfranchised. But here I am reading a magazine presenting good journalism under Rachel Morris’s astute editorship. Rachel is stepping back now from the role, but I am grateful for the issues she has presented (not forgetting worthy attention to books in Aotearoa).

It seems an eon since Wild Honey appeared in the world, yet it was only last year I was doing the online Ockham NZ Book Award celebration for it. But it is fitting to remember this project of love – I set out to celebrate and retrieve women poets in Aotearoa. The younger generations of women poets are vibrant, inspiring, active, revealing, political, personal, edgy, lyrical, path-forging and it is a joy to read them. To write about their work on Poetry Shelf. But I don’t write out of a vacuum. I write out of the women poets who preceded me. Who also wrote with vigour, with various connections to the personal and the political. And so to celebrate International Women’s Day, to celebrate women’s poetry in Aotearoa, I draw your attention to Te Herenga Waka University Press’s reissue of Ursula Bethell’s Collected Poems.

I have several copies of Wild Honey to give away. Email or DM or leave a comment if you would like a copy.

Let’s shine lights this week on all the wonderful things women are doing – but hey, not just women, everyone. Let’s shine lights on humanity’s goodness.

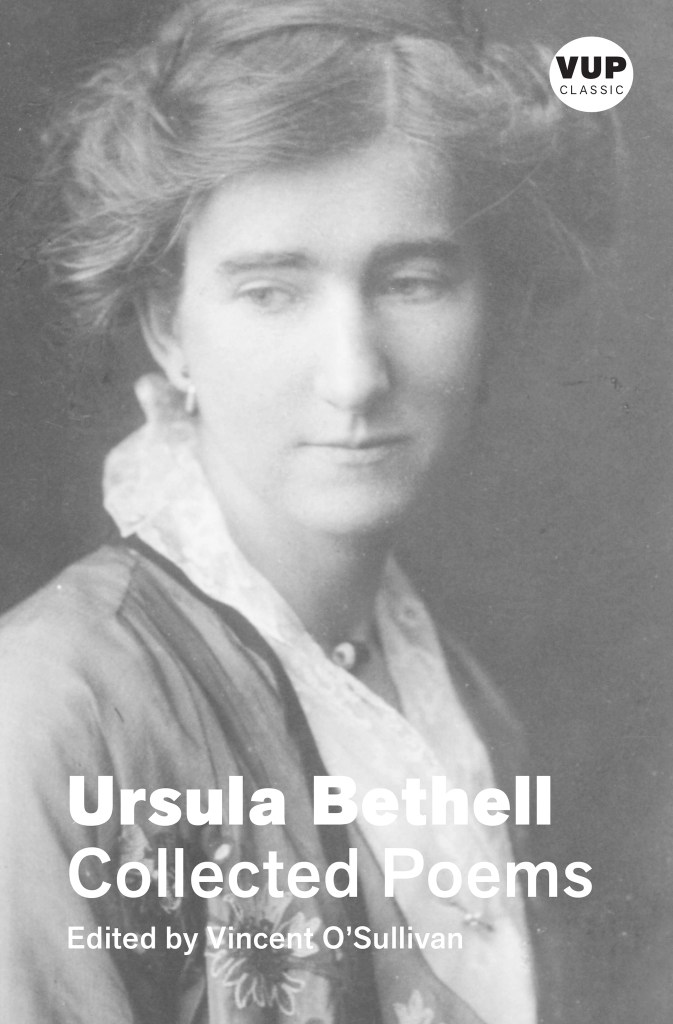

Ursula Bethell Collected Poems, ed Vincent O’Sullian, VUP Classic, 2021

Detail

My garage is a structure of excessive plainness.

it springs from a dry bank in the back garden.

It is made of corrugated iron,

And painted all over with brick-red.

But beside it I have planted a green Bay-tree

— A sweet Bay, an Olive and a Turkey Fig,

— A Fig, an Olive, and a Bay.

Ursula Bethell, From a Garden in the Antipodes, 1929

Ursula Bethell is the kind of poet I turn to when I want uplift, when I crave the poetic line as transport beyond ongoing despair at this sad-sack world. Ursula Bethell’s reissued Collective Poems is now a member of the VUP Classic series. Oxford University Press originally published the collection in 1985, and it was reissued in 1997 with corrections and a new introduction by editor Vincent O’Sullivan.

I utterly loved engaging with Ursula’s poetry in Wild Honey. I considered it in three parts:

“I want to approach her poetry as three distinctive garden plots with a memorial garden to the side: From a Garden in the Antipodes (1929), Time and Place (1936) and Day and Night (1939) and ‘Six Memorials’. You could consider the debut collection as poem bouquets for friends, the second as a poetry posy handpicked for Pollen after her death, while the final collection, a late harvest from the same ground, almost like a consolation bouquet for self. The memorial poems were penned annually on the anniversary, or thereabouts, of Pollen’s death.”

I wrote in my Wild Honey notebooks:

Bethell published three collections of poetry in her lifetime, all anonymously, with the poems chiefly drawn from a decade she devoted to writing, gardening and her cherished companion, Effie Pollen. For ten years, the two women lived in Rise Cottage in the Cashmere Hills, until Pollen’s premature death, at which point Bethell’s life was ripped to unbearable shreds. The more I read Bethell’s poetry and letters, and the more I muse beyond her characteristic reserve, I feel as though this is the woman to whom I would devote an entire book. She is a knotty collision of reticence, acute intellect, acerbic advice, crippling heartbreak and poetic dexterity. Bethell rightly counters the claim that she ‘knows no school mistress but her garden’, with the point that the garden was ‘a brief episode in a life otherwise spent’. Yet her gardening decade was the most joyous of her life, responsible for the bulk of her poetry, and a period she could not relinquish in letters and the grief that endured until her death. She moved back into the city with ‘no cottage, no garden, no car, no cat, no view of mountains’, no dearest companion and an impaired ability or desire to write poetry.

I was uplifted by individual poems and by the threads and luminosity as a whole:

“How can poetry ever match the joy and beauty a garden offers? Bethell brings us to the pleasure of words, the way words bloom and bristle. For Ruth Mayhew, a close friend to whom she dedicated a number of poems, Bethell builds her green garden symphony in ‘Verdure’: an abundant foliage of lemon, myrtle, rosemary, mimosa, macrocarpa. Without these variations, Bethell confesses she ‘should have, not a pleasaunce, not a garden/ But a heterogeneous botanical garden display’. The word, ‘pleasaunce’, is the spicy fertiliser waiting to explode the poem into new richness. Bethell favours flowers over produce, a pleasure enticement for the senses over fruit and vegetables for the kitchen (‘I find vegetables fatiguing/ And would rather buy them in a shop’. Her poetry ferments as a form of pleasaunce where the ‘plausible’, easily digested details of domestic routine, the house interior, daily conversations, intimate preferences and relations are sidestepped for words that provoke sensual and intellectual variegation in an outside setting.” from my Wild Honey notebook

To re-enter Ursula’s poetry is an act of restoration, just for a blissful moment, because it’s a way of feeling the warmth of the ground, the warmth of humanity (as opposed to its cruelty and ignorance). It is reminder that our literature offers so many rewards, on so many levels, and it is at times like these, poetry can be such necessary solace, respite, prismatic viewfinders, idea boosters. I am toasting the poetry of Ursula Bethell with thanks to Te Herenga Waka University Press.

Vincent O’Sullivan is the author of the novels Let the River Stand, Believers to the Bright Coast, and most recently All This by Chance. He has written many plays and collections of short stories and poems, was joint editor of the five-volume Letters of Katherine Mansfield, has edited a number of major anthologies, and is the author of acclaimed biographies of John Mulgan and Ralph Hotere.

Ursula (Mary) Bethell (1874-1945) was born in England, raised in New Zealand, educated in England and moved back to Christchurch in the 1920s. Bethell published three poetry collections in her lifetime (From a Garden in the Antipodes, 1929; Time and Place, 1936; Day and Night, 1939). She did not begin writing until she was fifty, and was part of Christchurch’s active art and literary scene in the 1930s. A Collected Poems appeared posthumously (1950). Her productive decade of writing was at Rise Cottage in the Cashmere Hills, but after the death of her companion, Effie Pollen, she wrote very little. Vincent O’Sullivan edited a collection of her poetry in 1977 (1985).

Te Herenga Waka University Press page