Summer 2016

that summer was heavy, thick

I felt myself weighted,

struggling to move through air

it was underwater with open eyes

breathless and pressurised

seeing everything through

the blur and sting

of sea water

my new breasts were tight and hard in my chest,

and I had to sleep on my back for the first time;

my body was an unfamiliar collection of bones,

brittle as shells, and freshly bleached hair.

it was an achingly empty summer,

it was bitten, itchy skin,

damp thighs rubbing on denim,

it was bare chested and freckled,

salt licking new scars

it was the season of lemons

softening in the bowl,

damp fur, and fingernails bitter and green

from tearing and linking

daisy stems

it was clotted black blood, sprinklers,

strawberries and razorblades,

it was warm, long nights alone

it was the summer of the 6 am hate poem,

the first summer the soles of my feet

grew thick and hard

and as I watched shadows stretch

and felt cool wind come off the water,

it was the summer

I fell in love with

myself.

Jess Fiebig

Jess Fiebig is a nationally-recognised poet, educator and performer living in Otautahi/Christchurch, New Zealand. Her writing has featured in journals such as Aotearotica, Catalyst, Landfall, takahē, Turbine, Poetry New Zealand Yearbook and Best New Zealand Poems 2018. Jess was commended in the 2017 and 2018 New Zealand Poetry Society International Poetry Competitions and was highly commended in 2019 Sarah Broom Poetry Prize. Her poetry explores themes such as madness, sex, love, family violence, friendship, drugs and dislocation. Jess teaches creative writing and is a tutor at the Christchurch School for Young Writers. Jess’s website.

‘She is currently living’ appears in Conventional Weapons, Victoria University Press, 2019

Conventional Weapons is Tracey’s first full poetry collection but she has been publishing poetry for over two decades. She was the featured poet in Poetry NZ 25 (2002) and has published Her body rises: stories & poems (2005). She has received multiple awards including the international Bridport Prize in 2014, a 2007 New Zealand Book Month Award, and Katherine Mansfield Awards in 2004 and 2001. She also won the 2015 Landfall Essay Competition, and was the recipient of the 2010 Louis Johnson New Writers Bursary.

Poetry Shelf reviews Conventional Weapons.

Victoria University Press author page

check layout 22/ 7

Manuhiri

(Visitor)

1

Her grandmother told her she was a child of Manu,

manushi, daughter of humanity, blessed

to be a visitor when she crossed the sea.

The wooden gate is a threshold with arms outstretched

in protection, the slow wash of green waters rhythm.

Rising notes of another tongue is the wailing of her mother tongue.

Her back, a billowing canvas is taking shape –

her grandmother’s tapping, tapping the geo-graphy of her

in colours of the monsoon rain.

She is dusk, light with all the distance around her.

She crosses the threshold and offers her grandmother’s verses,

a garland of old earth sounds for the new.

2

Blissful waters surround pain washed up over and over again.

She sits among silent voices, bodies twitching to utter

shame for carrying skin, coloured by others.

What’s a brown skinned woman to do

at the gates of a marae? The solidarity of colour

bears differentiation.

He opened to a stance defying rule, he said I am

connected to islands by water, I am connected to you

by colonisation.

The gates opened enough for her to raise her head.

3

Nga Mihi

Korihi Te manu, takiri mai i Te ata

Ka ao, ka ao, ka awatea

Tihei Mauri ora

Kua tau tenei manu hei manu, hei manuhiri, hei manu hari

Ko te takahanga waewae, ko te rere o te kupu

Ka tangi te ngakau, he roimata aroha

Ki te manawhenua, no koutou tonu te whenua nei.

He awe ko toku mama, he awe ko toku papa

Ma te huruhuru te manu ka rere

Ka rere i te ao, ka rere i te po, ka rere ki toku whenua ake

Ma Te ahi ka te manu ka ora.

Tena koutou katoa.

4

When the kuia holds her hand, a sacred place ignites.

You are a seed of the old banyan tree swept

from your grandmother’s lap.

Transplanted here, I see birds’ nests, singing insects and shoots bearing the weight

of you. I see strong branches making light of your path –

see how they are dropping roots –

she feels the earth quiver under her feet.

5

Across the table, she hears raging clouds roving

to make wave upon wave to become sea overhead. White peaks roughed up on waters

below are screeching

gulls. How can she say that she is a visitor

on a warm beach with sand beads

sketching a canvas stretched in her head?

6

She is a mirror of herself.

She is not a mirror of herself.

She is a scooped grain of memory,

of a love-song for a life lived

between her worlds.

1 The mihi for Manuhiri was prepared for me by Matt Gifford. It is made of two parts – the first is Māori proverb, the second part of the speech is an introduction of me to the hosts at the marae. The translation is as follows:

Nga Mihi (speech)

Part One – Maori proverb

Korihi Te manu, takiri mai i Te ata

Ka ao, Ka ao, ka awatea

Tihei Mauri ora

The bird sings, the morning has dawned

The day has broken

Ah! There is life.

Part Two – my speech introducing myself Matt references me as bird

Kua tau tenei manu hei manu, hei manuhiri, hei manu hari

Ko te takahanga waewae, ko te rere o te kupu

Ka tangi te ngakau, he roimata aroha

Ki te manawhenua, no koutou tonu te whenua nei.

This manu (bird) has descended as a manu (bird), as a visitor, as a dancing visitor

Through its dancing feet and its flowing words

Its heart cries, the tears of love

For you the home people, this is your land.

He awe ko toku mama, He awe ko toku papa

Ma te huruhuru te manu ka rere

Ka rere i te ao, ka rere i te po, Ka rere ki toku whenua ake

Ma Te ahi ka te manu ka ora.

My mother is a feather, my father is a feather

And it’s by their feathers this manu (bird) takes flight

Taking flight to the day, and flight to the night, From its own home land

Where the home fire burns, and gives this manu (bird) life.

Originally from South India, Sudha Rao lives in Wellington and has had a long standing involvement with the arts, primarily as a dancer. In 2017, Sudha graduated with a Masters in Creative Writing from the International Institute of Modern Letters, Victoria University, Wellington. Since 2012, Sudha’s poems have appeared in various journals and anthologies. These include two editions of Blackmail Press (2012 and 2014); an anthology of New Zealand writing, Sunset at the Estuary (2015) and in the UK anthology Poets’ quest for God (2016); Landfall, Otago University, Dunedin (2018),and an anthology of migrant voices called More of us published in March 2019. In 2014, one Sudha’s poems was on the Bridport Poetry Competition’s shortlist. Excerpts of her prose work, has appeared in Turbine (2018) which comprised part of her MA thesis Margam and other excerpts were read in two sessions on national radio RNZ (2018). Sudha is part of a collective of Wellington women poets called Meow Gurrrls, who regularly post poems on YouTube

.

Gail Ingram, Contents Under Pressure, Pūkeko Publications, 2019

Gail Ingram has published poetry and flash fiction both in New Zealand and internationally. She lives in Christchurch where she is part of a writing/ critiquing group of poets. Contents Under Pressure is her debut poetry collection and includes illustrations by her daughter, Rata Ingram.

Contents Under Pressure is in debt to a city; the poems navigate post-earthquake Christchurch. When I first held the book and flicked through the pages, I was reminded of flicking through a book to watch the drawings on the bottom corners move. Flick the pages of this book and it is poetry in disrupted movement: you get spiky angles, walls of text, bold against light, steps against missing bits, changing fonts.

The title is perfect: everything is under pressure – the fractured city and the contents of the book. This is the story of a city filtered through that of a mother / graffiti artist and her son, and both have different ways of coping with a city in pieces.

The opening poem ‘Definition: mother / graffiti / artist’ introduces just that: a mother who goes tagging in the city that continues to break. At times the pages of the book stand in for the tagged walls:

she sprays

airport walls in zen

tangles so strangers

trace poke-leaves

in sesquipedalian mazes

from ‘From below, the graffiti artist is’

I love this book because it shakes up what poetry can do while simultaneously bringing us in close, so searingly close, to human trauma.

An early poem returns us to solid ground: the mother and her sons are looking at a photo of the family tobogganing at Round Hill. It is a white hot shard in the collection that makes the rest of the poetry even more poignant:

Mum took the photo. I’ve got this picture of Dad resting his

arm across her shoulders —

Yeah, like a security blanket.

Yeah.

But now when I look at it, I don’t see us. I don’t know who

that family is, but …

I know the mountains —

The mountains are capable of moving.

from ‘She overhears the boys talking about the photo in the hall’

The portrait of the woman feels like a woman behaving out of character in order to relocate herself (her new character) in the new and shattered terrain. She leaves her familiar/unfamiliar daylight routines. She becomes someone other in the pitch dark night. At times the writing is in shards and spiky while at times it is lyrical:

She hasn’t gone out into the ink

of the night street yet. Here,

she exists, safe as a thief

in the stoma of their sheets

before she will slink through the open window,

creep along the dark passages of local streets,

and tap her own tune

on the city’s leaping drum.

from ‘The graffiti artist waits for the world to sleep’

The graffiti artist shows us the power of art to make both public and personal both ideas and feelings. And we can engage with this. We can be moved and we can be challenged. In ‘The graffiti artist as a teenager’, her art teacher had showed the class the ‘Cubist strokes of “Guernica””. She is learning what art can do:

At fourteen she learned the power of dots. That a

cluster could create a river pebble’s shadow, a

crease in a smile or the trail of cupped hooves on

farm soil. Forty pencils pattering in the class, and

the hexagon-window left free, high in the streaked

pupil, made the picture come alive as if it was her

paper skin under the shrapnel of sharp lead. (…)

There are many threads to track through the book. Equally captivating is the thread of the son thrown off kilter, with drugs, anxiety, physic textbooks. In ‘Expedition to the New World’ the mother and son are traipsing through the vegetable aisles where the poem’s punning supermarket title confirms everything is made strange and off-centre:

(…) She can’t find what they need. He

brushes past tins of spaghetti. Root-like tendrils on the

labels seem to take an interest in his passing, as though to

grasp for arm or ankle. He half-stumbles into the bags of

stalky cereal and utters a guttural sound, an earthquake

rumble that shudders up through his body to settle there.

On the back of the book Sue Wootton, Bernadette Hall and Bryan Walpert underline what a gift this book is. I agree. The poetry represents the way the shattering of familiar terrain shakes up everything: family, body, heart, faith, everyday routines, solid attachments. It shakes you as you read. It is intimate and it is wide reaching. It also shows the way art, language and a deep love of family carry you as you discover ways to resettle. A gift of a book.

Pūkeko Publications page

I have just mapped in my mind all the places I would like to be on Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day – I always love what Nelson comes up with, Featherston, Napier, Central Otago … and of course all the big cities. But this year I will be in Wellington hosting a lunchtime event at Unity Books (getting to hear some women read I have never heard before yeah!), then hearing some AUP New Poets hosted by Anna Jackson at Book Hound (also hearing poets I have mostly never heard read before) and finally going to Show Ponies (R18) (wow! what a line up!) at Meow.

I love the way bookshops, cafes, bars, universities, marae, schools and libraries are increasingly inventive every year in designing events and competitions – and poets appear all over the country. You could for example have brunch with Chris Tse in Hamilton!

Check out your route by clicking on the link and see below for mine!

Climate change and the plight of refugees are the focus of some of the 150+ events in this year’s Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day, taking place on Friday August 23.

Our annual celebration of writing and reading poetry embraces both the personal and political in a dynamic programme of events and competitions nationwide – from parks,

beaches, pavements and public transport to cafés, bars, bookshops, schools, university campuses, libraries, RSAs, community centres, marae and more.

The record number of events include:

Auckland’s ‘I Feel at Home, Away from Home – Blackout Poetry Workshop’ – that gives voice to our migrants and refugees; and the Theoradical Hobohemians hosting

‘An Interview with Charles Bukowski’.

Wellington’s ‘Show Ponies: A National Poetry Day Extravaganza’ – a late-night gig, featuring award-winner Chris Tse and other poets posing as popstars for the evening.

Wairarapa’s ‘Climate Positive’ – poetry, song and stories of positive action against the climate crisis with performance poets Extinction Rebellion.

Christchurch’s ‘Poets in Our Tūranga’ – a six-hour poetry marathon at the new Tūranga Central Library, featuring more than 40 local poets and writers, and 2019 Ockham

New Zealand Book Awards poetry category finalist Erik Kennedy.

Dunedin’s ‘Changing Minds: Memories Lost and Found’ – a poetry competition for adults inspired by their experience of dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease.

Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day includes appearances by the winner of the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry in the 2019 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, Helen Heath, who will deliver a workshop at Hagley Writers’ Institute in Christchurch on Saturday, August 24.

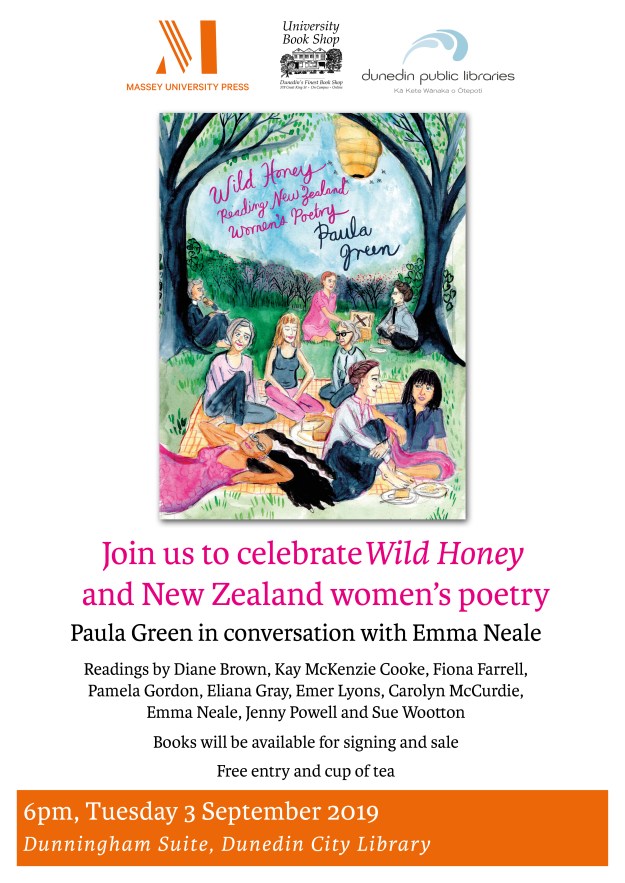

Poetry category finalist, Therese Lloyd, will take part in a celebration of Paula Green’s magnum opus, Wild Honey: Reading New Zealand Women’s Poetry at Unity Books in Wellington.

In the lead up to August 23, Phantom Billstickers will bring poetry to our communities with an epic street poster campaign. All four 2019 Ockham poetry category finalists, including Tayi Tibble, will feature in Phantom Billstickers’ national super-size Poetry on Posters campaign.

Nicola Legat, Chair, The New Zealand Book Awards Trust, says ‘One of the themes of this year’s events is a focus on social issues. Events focused on climate change and the issues facing refugees are among them, and this shows how relevant and useful poetry is as a way of confronting and addressing some of our wicked problems.’

Held annually on the fourth Friday in August, #NZPoetryDay sees poetry royalty join forces with poetry fans from all over Aotearoa in an action-packed programme of slams and rap, open mic and spoken word performances, pop-up events, book launches and readings. There are 24 poetry contests to enter. Many of the programmed events will be open to the public and free to enjoy.

Established in 1997, National Poetry Day is a popular fixture on the nation’s cultural calendar and one that celebrates discovery, diversity and community. For the past four years, Phantom Billstickers has supported National Poetry Day through its naming rights sponsorship.

For full details about all the events taking place on Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day, including places, venues, times, tickets and more, go here.

Glenburn

Even in the face of an icy wind, the stillness

dazzles us, and we journey south to the dulcet honey.

He falls silent, the din left destitute, far

from the hive. The sound of his laugh, it rises

and becomes music, a vein of sun that is in him

like a mountain. Appearances remain objects of barter.

All the calm. All that fury. We cross a threshold

to witness the unbidden cloud. Our chamber of words

sweetened as if made of honey or beeswax,

for we arrive at last, the smell now in him of hive.

We will eat bread and cheese, forgetting the northern

city, the pull of the ocean. He moves with his sight

fixed on stillness, finding a fickle appearance

like a star behind slow speech. All that fury. All that calm.

Where will we find the scale of love? The journey south

undoes the mountain of cloud. His own incubus

the riddle that is land. We are certain that buildings

will appear in the stillness, kept alive by our eyes.

Paula Green

from Crosswind, Auckland University Press, 2004. Also published in Dear Heart: 150 NZ Love Poems, Random House, 2012.

Note from Fiona Farrell

My favourite poem? I had enough trouble selecting 25 recently for the IIML annual anthology.

So, a single poem? Should it be one that has repeatedly popped into my head at odd intervals over many years, a single line, a phrase, one of those little handgrips that keeps me from falling? Should it be a poem that belongs so strongly to a time I like going back to in my mind, that it arrives fully packed and tagged to memory? Or the one that touched me so much because it was a gift from a friend and unexpected and it said something I loved hearing? Or the one that was very old and strange? Or the one that made something I knew well gleam with newness so I noticed it again as if it was for the first time? Or the one I read this morning that has left the day feeling just great?

I’ll go with that: Paula Green’s ‘Glenburn’ because it speaks to the strangeness I feel moving to Otago again after many years absence. And to the feeling of discovering it – and it might as well be for the first time – in the company of someone I love who has other eyes to bring to the journey south. And to my knowledge of Michael Hight’s paintings of beehives, so there is an illustration – not any one painting, but many – lurking beside the words.

And it speaks too to a feeling that’s been growing steadily since I came here, that it’s all so fragile, this beautiful golden south. Last night I talked to a woman fighting subdivisions in Arrowtown. ‘It’s going,’ she said. ‘Queenstown, and Wanaka and Arrowtown and the lakes.’ Pockmarked with 400 house subdivisions, an airport proposal which could go anywhere, hotels and resorts and dairy conversions.

This poem of Paula’s makes me think about love: for people and for a landscape.

Fiona Farrell publishes fiction, non-fiction, poetry and drama. She lived for many years at Otanerito on Banks Peninsula but has moved recently to Dunedin.

Paula Green has just published two new poetry collections (Groovy Fish, The Cuba Press) and (The Track, Seraph Press) with Wild Honey: Reading NZ Women’s Poetry (Massey University Press) out early August.

Tracey Slaughter, Conventional Weapons, Victoria University Press, 2019

Tracey Slaughter came to my attention as a fiction writer; I adored deleted scenes for lovers VUP, 2016) and lauded it in my SST review:

Tracey Slaughter’s daring short fiction deposits you on a rollercoaster, hoists you in the air, puts you in a dank, dark cupboard to eavesdrop, spins you round and round, makes you feel things to the nth degree.

Conventional Weapons is Tracey’s first full poetry collection but she has been publishing poetry for over two decades. She was the featured poet in Poetry NZ 25 (2002) and has published Her body rises: stories & poems (2005). She has received multiple awards including the international Bridport Prize in 2014, a 2007 New Zealand Book Month Award, and Katherine Mansfield Awards in 2004 and 2001. She also won the 2015 Landfall Essay Competition, and was the recipient of the 2010 Louis Johnson New Writers Bursary.

Like her fiction Tracey’s poetry is unafraid of dark subject matter: violence lament teenage eating teenage not eating abortion trauma. You will also find sex need desire love. The subject matter is important but it is the poetic effects that first strike me. There is an intensity of rhythm, an insistent beat that holds a poem together like a subterranean heartdrum, a breath metronome. It is no surprise that Tracey was (and is?) a drummer.

We deepdish kiss in the purple of your parents’ lounge,

a bunker plump with buttoned vinyl, fringed

with cocktail lamps. Your little brother doctors himself

a tower of afterschool toast and shovels into the corduroy

beanbag, watching claptrap TV—we’ll lip-sync those jingles

with their punchline chords the rest of our lives;

from ‘archaeological’

The beat in this two-and-a-bit page poem catches the intensity of after-school kissing, the heightened breath as the poem ‘sucks’ in detail of tongues and pashing, with an eye looking sideways to make the citrine kitchen and the purple lounge pulsatingly real. I am bowled over by the syntax, by the surprising juxtapositions of words, the lithe rhyme. I need to let the sonic impact sink in deep and savour the exquisite word play. Yes the young kissers are ‘archaeological’ but so too is the poet as she digs deep for flakes of the past and reposits them in the present tense.

The poem ‘the bridge’ also employs lithe syntax and rhythms to replay the urgency of kiss and touch:

Let feet slip on

sills of shell, a spiral

perimeter of crush.

Currents eel

the light into

muscled canals we need

to oar & plough, tough-thighed

in the bridge’s underworld.

Often the poems are made electric by the present tense. The opening poem ‘she is currently living’ is a startling portrait, written like a mantra, all lower case, even after the full stops, so you are compelled to keep listening to ‘where’ she is currently living:

in a dead-end off jellicoe. in the waiting room of blue vinyl fear. she is currently

living in supermarket flowers that whisper buy me in their middle-class plastic.

she is currently living in a red metal playpen riding her stepsister’s rocking horse.

If Tracey’s aural dexterity keeps you on your reading toes so do her shifting forms. There are long form poems, bite-size pieces, block prose, fractured lines, lists, multiple choice. The poem ‘how to solve and 18-year sadness’ sits on the page like heart break – the heart hinted at, the break holding apart past and present, the sadness hiding in the crevice. Another poem ‘horoscope (the cougar speaks)’ sets word clusters against left and right hand margins. The poem with its film-noir lighting centres desire, attraction, loneliness, suicide drifting song lyrics that are cut off short as the speaker finds her way:

there are girls to pick

the wings off

but I’m not one of them

And now the subject matter. For me Conventional Weapons foregrounds character, women characters, which makes this book dig even deeper under my skin. The experience is often attached to trauma, the settings lit up in neon detail, the emotional core razor sharp. I posted a piece on Poetry Shelf from ‘it was the 70s when me & Karen Carpenter hung out’ and even in that brief extract the effects were incandescent. This is a poem of youth, song lyrics and singing, macramé, neon lights, freezer food, the backseats of cars, orange lounges, soap operas, instant things but it is also a poem of vomit and of bodies eating and starving, of the traumatic smash of eating disorders.

me & Karen carpenter

blu-tacked heartthrobs

to the hangout

wall & lay down

under our own gatefold

smiles. The ridges of our mouths

tasted like corduroy & the hangout

door was a polygon of unhinged

ultra-violet. We stole lines from stones

& rolled them like acid

checkers on each

other’s tongues, testing

the discs of our tucked spines as we

swallowed. (…)

When I return to the poem ‘horoscope (the cougar speaks)’, I return to the spike in the poem’s flow, the suicide that cuts into you as you trace the portrait of a woman:

& that last verse

is chloroform

*

don’t come

back with your bad

translations of love

one writs italicised

with scars

‘the mine wife’ is another imagined portrait; a long poem that features the wife of a miner lost in the Pike River disaster and the wife’s ‘grief is opencast’. In Wild Honey I write about the way poets might step into the shoes of another’s trauma, tragedy, loss, grievance, dislocation, wrongs, grief in order to make public horrific things both as a distant and/or close witness. Is this trespass? Is this keeping trauma and human wrongs in public view? For centuries writers have imagined beyond their own experience. In this poem I am heart struck by the way a woman continues to live alongside death, in the fist of life once lived, in the daily routines of food and laundry, in the coming up for air from the dark.

to stand at the mouth

takes a long journey. It’s like

a cathedral to all

we’ve done wrong. I thought

seeing it would cave me in. But it’s the peace

of the place that doubles me over.

The birds go on dialling

God. Even without you, the trees

don’t come to a standstill. Healing is

not clearcut. Air makes the sound of where

you were last seen. I listen

for scraps in the hush.

Grief is opencast.

Tracey’s poetry reaches me just as her short fiction has: her daring poems deposit you on a rollercoaster, hoist you in the air, put you in a dank, dark cupboard to eavesdrop, spin you round and round, make you feel things to the nth degree. I can think of no other local poet who has this effect on me. The collection will slip under my clothes and travel with me for months. It is a book I feel and it is a book I think and I adore it.

Victoria University page

Rae McGregor review at RNZ National

Jack Ross launch speech (with images)