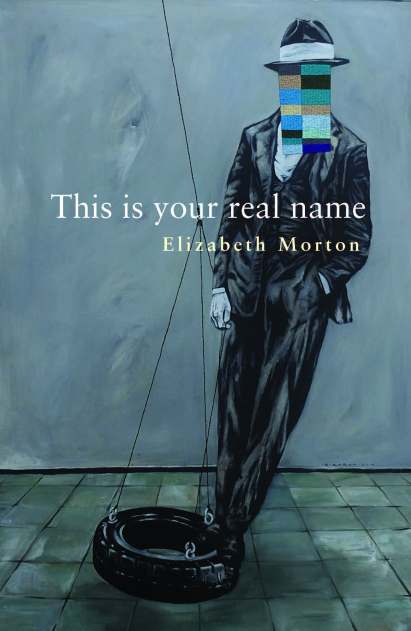

Elizabeth Morton This is your real name (Otago University Press, 2020)

Elizabeth Morton’s launch scraped in by the skin of its teeth recently, but I thought it would be lovely to do an online version and get Poetry Shelf Lounge rolling. You can read and listen for morning tea with a short black, afternoon tea with your favourite tea, or a glass of wine or beer this evening.

At the bottom of the post, I have put a selection of good bookshops where you can buy or order the book online (this is a list in progress, please help me fill the gaps).

Tracey Slaughter launched the book.

Split the pages of Elizabeth Morton’s This is your real name anywhere & you are in the pulsing presence of questions that cut to the very heart of poetry: How much, if anything, can language actually touch? How much of our experience can we ever name? How much can poetry reach past the stars smashed into the emergency-glass of daily-living & offer the kind of voice that leaves more than a bloody trace, that makes a vital difference. ‘Poetry wallows between question marks/police? fire? ambulance?’ says a piece that opens with telephone lines exploding in a gaze pushed to the edge – how much can language ever hope to halt pain, to offer connection, to help in such a crisis? ‘Deep breaths,/say the operator’ within that poem, but ‘inside the communications centre/the desks are inconsolable.’

‘There is no touching the black heat at the centre of things’ another early poem entitled ‘Inside-out’ declares – and yet travel through the bolted internal doors and bleak domestic corridors, the blighted global landscapes and glinting dystopias of Elizabeth’s collection & you know you’re in the hands of a poet who, like Plath or Sexton before her, has all the dazzling surreal command of language to reach to the core of that black heat, to make it speak.

‘Inside-out’ concludes with a widespread vision of ‘a wreckage of stars’ – but the volume goes on in piece after luminous piece to chronicle the work of salvage, of a self bent on using every particle of language to dig through the ruins, rewire the evidence, sustain the spark, relight every shard.

These are poems that speak again and again from both the inside and the outside, from both the blasted solar plexus of private traumas and the slow-mo devastations of the wider planet – over and over the poems flicker from hallways tremoring with personal pain to the ‘casual terrorism’ of history, taking an ‘aerial photograph’ of a suffering earth with the same kind of acute irradiated poetic lens that it turns on the lone & isolated heart. Whether it’s the stranding of a single life caught in the driftnets of personal desolation, or the mass beaching of a populace oblivious to the global damage they’ve done, Elizabeth’s language zeroes in on the waste & makes us see the interconnections: whether it’s steering the reader through burning towerblocks or coldblooded wards, past disinterested drone strikes or through achingly-handled small-scale solo losses, the breathtaking scope of poetic skill with which she charts her urgent scenes makes the reader feel every detail, feel the meds and the headlines catch in our throats, feel the doors locked and the altitude dropping, feel the kiss blown against the quarantine window & the distant ‘circle[s] of blood’ left on political screens.

These are poems that detonate and sing, that ring in the ear and sting in the political consciousness, and linger in the bloodstream long after they’ve stained your eye. They’ll also make you outright belly laugh: ‘I’d marry Finland. I’d blow Nicaragua. I’d shag Australia if she wore a paper bag’ states a slapstick look at politics that plays wicked & sacrilegious footsie with stereotypes. With the same comedic weaponry ‘How I hate Pokemon but I can show restraint and just talk about my adolescence’ gives a gore-soaked rundown of methods to slaughter innocent anime, and ‘In the next life’ tracks Wile E. Coyote speeding to collide with another booby-trapped piano or hurtling freight train. But of course, under the cartoon bloodsport there’s another violence being expressed: ‘I’m from the wrong cartoon she says…There is no/acid in my stomach to digest the sadness’; ‘I spent my teens/hyperventilating in elevators…yanking at emergency cords’ – that’s what lurks beneath the funny foreground of these onscreen critters and their messy calamities.

‘This is not a joke’ warns another poem, parading a cast of backwoods bar-leaners and big boned nobodies, its humour always ready to brim with ‘a metaphor so sad it makes grown men sob and jerk off into the same handkerchief.’ The counterstrike to comedy is always coming, the punchlines always poised ready to gut you. We might snicker when we’re introduced to a blowsy homespun oblivious America, but when she ‘order[s] Big Mac’s and Napalm’, lazily erases continents & watches bodycounts rise from her consumerist couch, the smile is wiped off our faces. And when the pronouns shift in this poem to fold us into complicity, as they do to such clever & ethical effect throughout the collection as a whole, we too are left standing with supermarket bags and shotguns/baffled and alone.’ That moment of aloneness – whether it’s the self turning figure-eights of final need or the last polar bear ‘pacing his cell, as the credits go down’ – is the place which the poems often return us to: ‘I wonder whether you know/you are melting’ this poetry asks with chilling economy. Over and over we find trapped ourselves in that phone booth, as in the masterpiece ‘Aubade’, where the glass is ‘skull-cracked’ and the world seems only to have ‘hold music’ to offer us. But even in this moment of exigency, with our ‘hearts in []our horror mouth’ & all the lines crossed, language is held up as ‘the loneliest miracle’: because we still use it to ‘pray, into the receiver’ hoping for a sign on the other end, some voice to come back from the empty page. ‘Writing is a political act’ the poem insists, even from this place. Even if all it can sometimes do is trace ‘the face of the enemy,’ or chalk round the bodies of selves and lovers we’ve lost; even if all it can sometimes do is echo the bleak dialtone inside our chests, its utterance ‘sets you apart’ the voice of ‘Aubade’ repeats to the sufferer.

Elizabeth had already set herself apart as a poet of breathtaking force, edge, intensity and empathy – This is your real name is another stunning, irrefutable, crucial book, a fearless personal testimony and a blistering political act. It goes to the places we need poetry to go to, places that only a language loaded with heart and shimmering with pressures can name. It smashes the glass.

Tracey Slaughter

Listen to Elizabeth read ‘Tropes’:

Stranding

We were never alone, pushing up loam on a blackened beach.

We kicked our tails like we were trying to escape

the outline of ourselves. We came ashore, two by two

with our cutlasses and compasses, with our baleen smiles

and bad attitudes, with our dead-end marriages and dreams that choked

in drift nets. We were never lost. We knew the shoreline better

than we knew our own purposes. We were a quarter into lives

that stood us up from the water-break, that left us gasping

by the river mouth, blistering under wet sacking,

our eyeballs fierce with the evening sun.

We wanted the attention. We wanted to arrange ourselves

upside down and scattered like something infinite. Like stars.

We follow each other to the end of the beach

and sing something that reminds us of bone

and the million land-flowers our mothers spoke of,

and the kamikaze heritage, our fathers and their fathers,

who recognised a vague phosphorescence

and shadowed it into the salt marshes, dreaming of air.

Elizabeth Morton

ELIZABETH MORTON grew up in suburban Auckland. Her first poetry collection, Wolf, was published by Mākaro Press in 2017. She has placed, been shortlisted and highly commended for various prizes, including the 2015 Kathleen Grattan Award, and her poetry and prose have been published in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States, Ireland, Australia, Canada and online. She has completed an MLitt in Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow.

Otago University Press author page

Let’s support our books and authors. Most importantly you can order this book online or visit your local bookshop. Here are a few choices (new books):

Whangārei Piggery Books Porcine Gallery

Auckland The Women’s Bookshop, Time Out Bookstore, Unity Books, The Book Lover(Milford), Dear Reader

Matakana Matakana Village Books

Hamilton Books for Kids Poppies Bookshop

Tauranga Books a Plenty

Rotorua McCleods

Palmerston North Bruce McKenzie Bookseller

Whanganui Paiges Gallery

Gisborne Muirs Bookshop

Napier and Havelock North Wardini Books

New Plymouth Poppies

Featherston Loco Coffee and Books, For the Love of Books

Carterton Almos Books

Masterton Hedkeys Books

Martinborough Martinborough Bookshop

Wellington Marsden Books Unity Books, Vic Books

Petone Schrödinger’s Books

Nelson Volume Page & Blackmore

Christchurch Scorpio Books University Bookshop

Queenstown BOUND Books & Records

Manapouri The Wee Bookshop (no website?)

Twizel The Twizel Bookshop

Dunedin University Bookshop