THE TO AND FROM OF POETRY

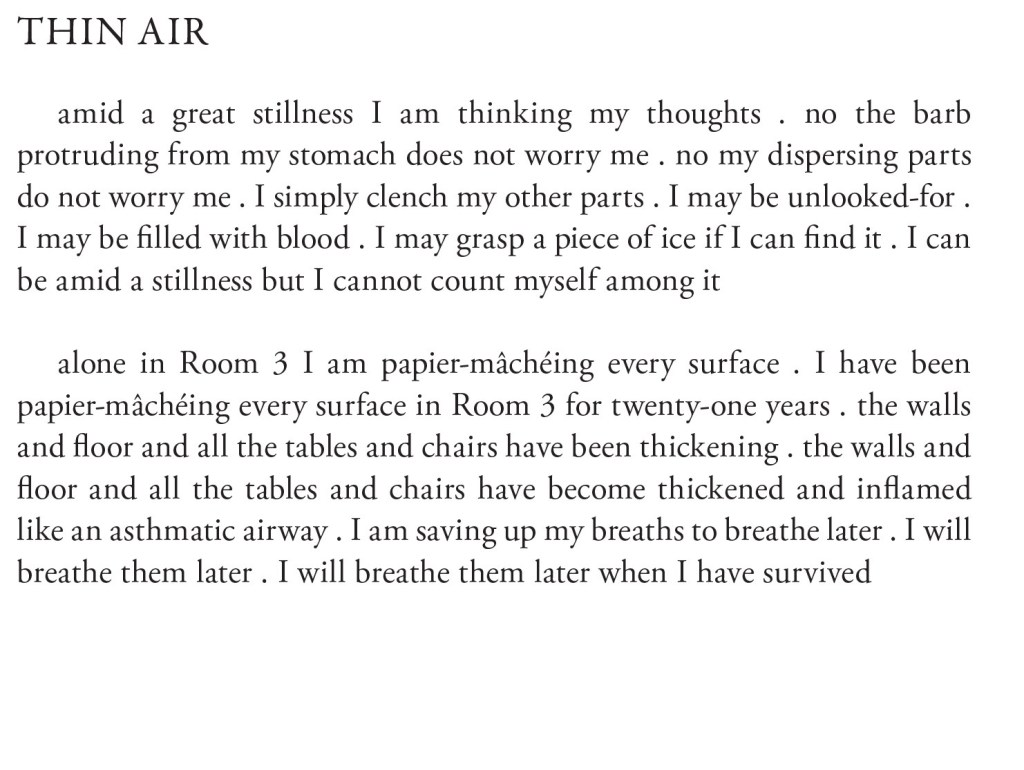

Murray Edmond’s poem ‘A translation of one of the sonnets of the importunate’

Poems are written ‘from’ – from the author – and poems are sent ‘to’ – to the reader. The poem itself, the ding an sich, needs both its writer and its reader to exist; or perhaps it would make more sense to say, ‘to accomplish its existence.’

Any poem can be an occasion to kōrero about poetry. And this is what I’d like to do. Having once written the poem, when you go back to it, you realise you are the reader and you find the poem is staring back at you:

‘Tell me what you make of me now,’ the poem says.

‘Okay, poem, I shall try and do this.’

Poems contain within themselves some form of address, which is why one always needs to ask those old questions:

Who (or what) is speaking in the poem?

Who (or what) is being spoken to?

And what is the nature of this speech – does it tell a story? Does it tempt you to agree with a proposition? Does it reveal a surprise? Is it trying to achieve something – does it petition? Persuade? Plead? Threaten? Demand? Seduce? Okay, so, what is the poem doing?

And that further question: What kind of poem is this?

The poem of mine that I have chosen for this kōrero importunes. That’s the action of poem. It is called ‘A translation of one of the sonnets of the importunate.’ The importunate speak.

Before moving to the next questions, best you have a chance to read the poem for yourself, dear Reader; after all, it is you who shall complete the poem as its reader. For the purposes of this exercise, I, once the author, am now of your kind, a reader too. And, remember, we may always and often disagree:

They brought those fêted seals in bells and hats

and leis by fated sails from ocean bowers

with cargo load of sated foals and gold

crew of fetid souls – white warlock on the bridge

our failed ships drooped before this armada

lagoon spilled shells and pestilence of coral

so that we took forced spoils and chopped them up

in slithers speech degrades – swathed fools

worked days of filched sleeps and broken skin

slipped our secret saviours feasts of scraps –

those zealots who sequestered skeins of poison –

lovers searching under sheets for signs of solace

swift wealth consumes our livers’ breath

sweet succubus send annihilation of the goat

In the last line the poem does reveal to whom it speaks. There is that moment of specific address: ‘sweet succubus.’ A succubus is importuned.

Succubuses (or slightly less hissy, succubae), supernatural entities, better known as demons, are probably folkloric in origin, though they pop up in Jewish religious texts and stories, as well as in the form of ‘Jinns’ in Turkey; and they caused consternation to such Christian thinkers as St Augustine, Thomas Aquinas and James 1st of England – they were anxious if these demons could conceive offspring from humans. In Brazil you might find one in a river looking like a dolphin (boto), but always wearing a hat so you don’t notice the demon is breathing through the top of its head. Though a succubus is female and its male equivalent is called an incubus, there’s a strong feeling that a certain gender fluidity allows a succubus to flip over into an incubus and back again into a succubus, as required. Put simply, these demons come and seduce you and then kill you via sexual desire and ravishment. They annihilate you. The father of Gilgamesh, hero of the eponymous Sumerican epic, seems to have been an early precursor of an incubus; while in The Zohar Adam’s first wife, Lilith, becomes a succubus. Pope Sylvester (999 – 1003) apologized for having a relationship with a succubus, but there may have been an element of rationalization involved in his story

The voice of my poem importunes a succubus to ‘send annihilation of the goat.’

The action of the poem ghosts the action of a prayer, in that a prayer (while not being a performative speech act) is a form of words that try to make something happen by the act of being spoken.

Well then, what kind of poem is this? Its title proclaims its origins and its classification.: ‘A translation of one of the sonnets.’ ‘Translation’ means that here exists a previous form of the poem in a different language – what you are reading is a step away from the original. And ‘one of the sonnets’ gives us a particular kind of poem.

The inventor of the sonnet, Giacomo de Lentini, writing in Sicilian in the thirteenth century, was a lawyer, a pleader, in the Sicilian court of Frederick II, an Epicurean atheist whom Dante placed in the sixth layer of hell and Nietzsche called ‘the first European.’ Since then the sonnet has been relentlessly propagated. When Elizabeth Barrett Browning composed her Sonnets from the Portuguese in the mid-1840s, she initially wanted to call them ‘Sonnets translated from the Bosnian.’ Husband Robert used to call her ‘my little Portuguese’ and so the change of name allowed her to embed the private reference (‘Yes, call me by my pet-name’ – Sonnet 33) as well as posing the poems as translations, thus securing the best of both worlds, which sometimes poems aim to do.

Since poets never write alone, it’s worth mentioning that the poet who was on Elizabeth’s mind was Luis de Camões (1524-1580), celebrated ‘national poet’ of Portugal. Camões may have been the first significant European poet to cross the equator into the Southern Hemisphere, spending periods in Goa and in Macau and being wrecked off the coast of Cambodia, experiences which contributed to his epic Lusiads. But he was also a sonneteer.

The sonnet itself is a topic for sonnets. In English, Keats wrote ‘On the Sonnet’ and Wordsworth wrote ‘Scorn not the sonnet’ (and Shelley wrote a sonnet, ‘To Wordsworth,’ a lament for Wordsworth’s betrayal of his commitment to ‘truth and liberty’). I think my favourite is Edna St Vincent Millay’s ‘I will put Chaos into fourteen lines.’

With my sonnet, I wished to include the presence of chaos within the fourteen-line form. The word succubus comes from the Latin word ‘succuba,’ meaning a ‘paramour,’ which in its turn derives from ‘sub’ meaning under and ‘cubare’ to lie. The succubus will come and lie under you while certain erotic dreams occur. Entirely the fault of the succubus. In an analogical way, the form of the sonnet ‘lies under’ my poem. Desire beneath the chaos.

In his Handbook of Poetic Forms, Ron Padgett writes that the ‘sonnet form involves a certain way of thinking.’ Padgett points out, ‘if you want to write in the sonnet form, it’s good to understand the concept of “therefore”.’

Therefore, the first quatrain of my poem evokes an incursion bringing disaster – ‘by fated sails from ocean bowers’ – the arrival of pestilence, pandemic, plague, prostration, perhaps a colonization, with the fatal combination of ‘crew’ and ‘white warlock on the bridge.’

The next quatrain informs that, like ‘swathed fools,’ resisters to this ‘armada’ are helpless. Therefore, in the third quatrain, such slow plans as the nurturing of ‘secret saviours’ and the plottings of ‘zealots’ are frustrated by the concitation of the desire for destruction. That desire, ‘annihilation of the goat’ in the poem’s final words, may be for self-destruction or the miracle that will drive the invaders out. ‘Whose annihilation?’ is the question. The sonnet is a coded message from the damned who can only speak in riddles. This is a poem that does not declare itself because it is written from a situation in which it is not safe to do so. The language sounds strange, tantalizing, alien, indeed, translated.

One presumes there are more sonnets to come which might explain. As this garland of sonnets is unwound, will poetry make something happen? ‘Poetry makes nothing happen,’ as Auden mentioned in his poem on the death of Yeats. And that may just be its achievement. Poetry can make nothing happen. In reality nothing can’t happen. But in poetry it can. That’s what the reader finds, when they invent out of this nothing.

Every poem is a kind of collaboration. When you write a poem you begin by collaborating with the reader’s idea of what a poem is: you may want to subvert this idea or confirm it, but you are complicit from word one. Then the poem has a form that is one you borrow or one that you claim (against what odds it is hard to measure) is your own. The form and the reader are both ‘others’ of your poem. Where does that leave your poem? And you – are you the ghost of your poem? Is the reader the reader conceived from your poem?

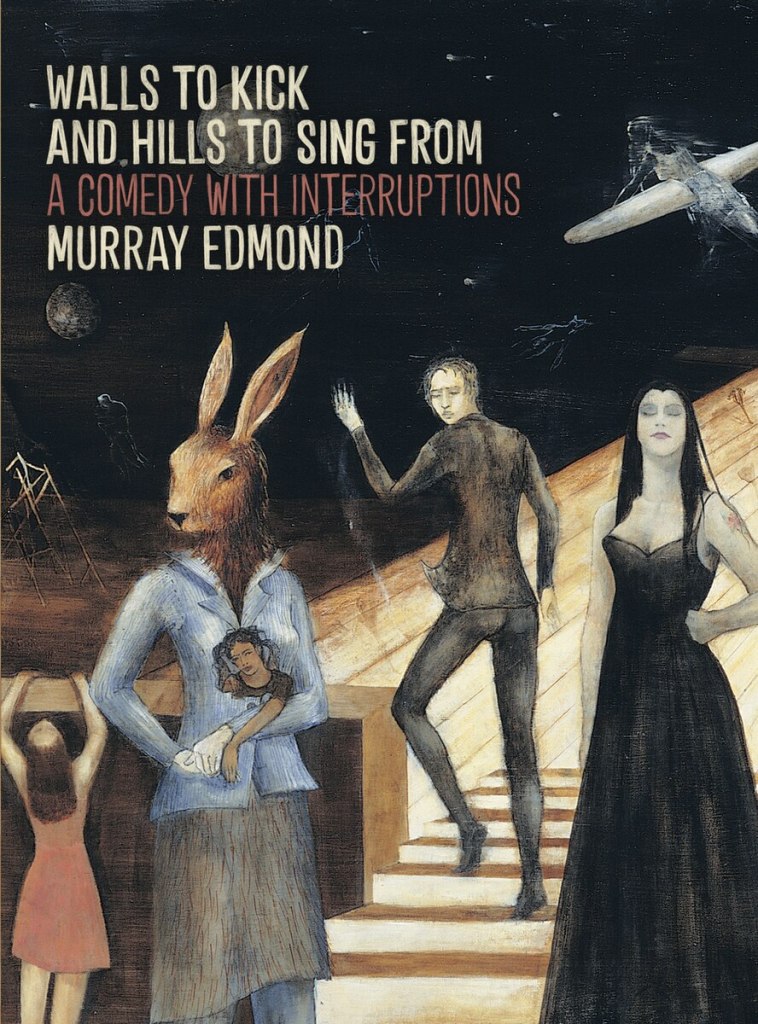

‘A translation of one of the sonnets of the importunate’ appears in Walls to Kick and Hills to Sing From: a comedy with interruptions by Murray Edmond (Auckland UP, 2010) p.19.

Murray Edmond: Born Kirikiriroa 1949, lives in Glen Eden, Auckland. Poet (14 books, Shaggy Magpie Songs, 2015, Back Before You Know, 2019); critic (Then It Was Now Again: Selected Critical Writing, 2014); fiction-writer (Strait Men and Other Tales, 2015); editor, Ka Mate Ka Ora; dramaturge for Indian Ink Theatre. Forthcoming: from Indian Ink, Paradise or the Impermanence of Ice Cream, Q Theatre, October 2020. Ka Mate Ka Ora #18, October 2020. Time to Make a Song and Dance: Cultural Revolt in Auckland in the 1960s, from Atuanui Press in 2021.

You can hear Murray in conversation with Erena Shingade here. He reads this poem at the end.

Auckland University Press page