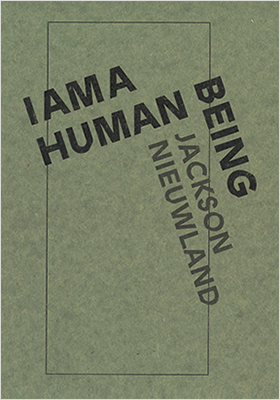

I am a human being, Jackson Nieuwland, Compound Press, 2020

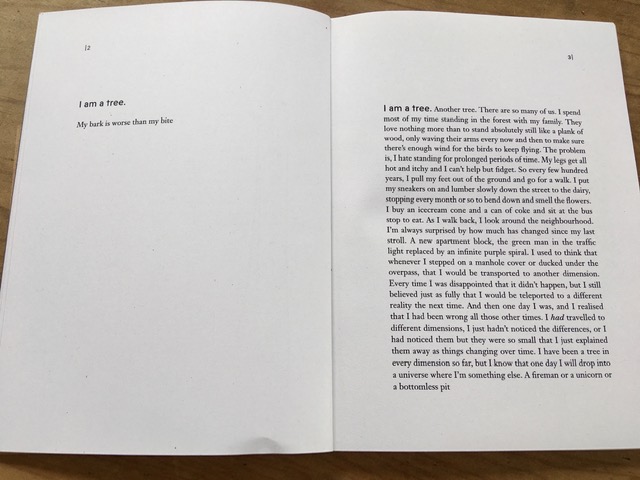

Sometimes you pick up a poetry book and you know within a page or two, it is a perfect fit, a slow-speed read to savour with joy. That’s how I felt when I started reading Jackson Nieuwland’s I am a human being. I love the premise embedded in the title, that in turn generates a sequence of poems that form a secret title list poem (I am an egg, I am a tree, I am tree, I am a beaver, I am a bear, I am a dog, I am a bottomless pit, and so on).

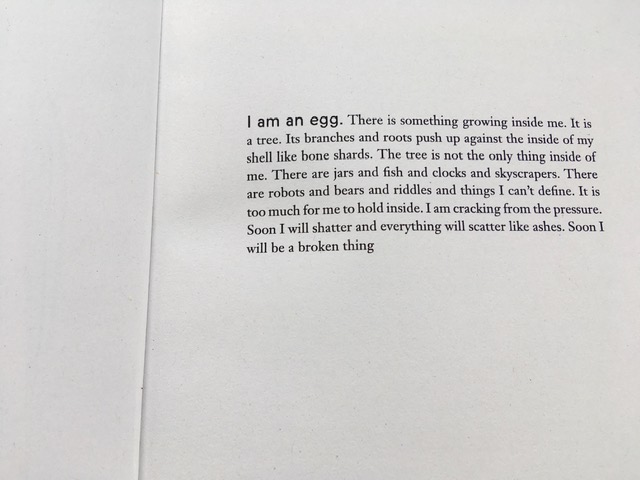

The opening poem offers an image that, in its exquisite and heart-moving detail, underlines the range of the book: physical, metaphorical, fable-like, metaphysical, autobiographical. In one poem the speaker suggests they are not quite sure who they are yet, that there is no single word that adequately defines them (‘agender, genderfluid, trans …’). This book, so long in the making, lovingly crafted with the loving support of friends, with both doubt and with grace (think poise, fluency, adroitness), this book, in its lists and its expansions, moves beyond the need for a single self-defining word.

Instead we are offered the image of the egg – and the way we hold a universe of things inside us, and that sometimes we might break.

This is intimate poetry. This is slowing down to observe the quotidian, the daily comings and goings, the things you see and feel when you stop and reflect and imagine, that then tilts to surprise. There is uplift and there is slipstream.

This is contoured poetry because it ignites so many parts of you as you read. You will laugh out loud as you read. You will feel the poignant witty wise delightful magical joy. The shifting melodies. There are keyholes to light and keyholes to dark. The speaker speaks of outsiderness, of what it is to fit, and what it is to not fit.

Sometime you will turn the page to a glorious pun.

Sometimes the vulnerability is a sharp ache above the surface of the line. This from ‘I am version of you from the future’:

Your past self looks at you with sympathy.

They pull you into a tight hug.

You begin to sob

releasing years of tears

that had been held inside

due to the conditioning you received

from a patriarchal society

and the overload of testosterone

pumping through you body.

As you sink into your own embrace,

the two versions of you merge into one,

and you begin again

given a chance to do it all over

but differently this time,

with an open heart

like quadruple bypass surgery.

The risk of death is high

but what other choice do you have?

I am a version of you from the future.

This is just the beginning—

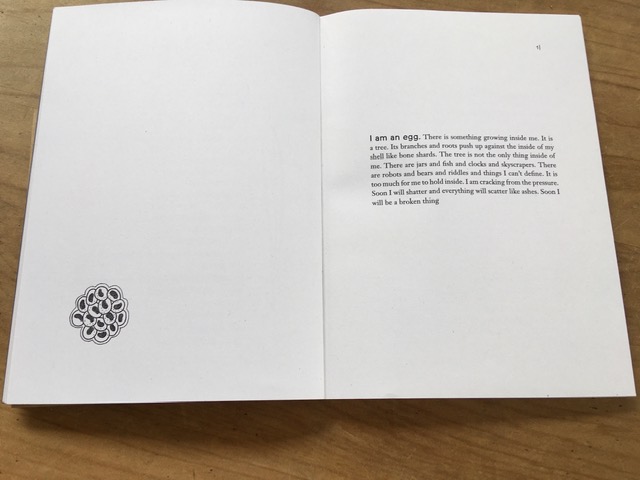

I am a human being is my favourite poetry book of 2020 so far. I like the addition of Steph Maree’s line drawings. I like the way the poetry stretches in its imaginings to draw closer to an interior real that is never fixed. I like the way the poetry is both anchor and liberating kite. I like the acknowledgement that, in order to know who you are, you need to embrace many things. I love this book so very much from first page to last. In the endnotes, the page where the poet gives thanks, I read the best acknowledgement ever:

And thank you for reading

this book. I’ve gone back and

forth with myself for years

about whether these words are

worth anyone’s time. It means

the universe to me that you’ve

read all the way to the end. I

hope you found something that

meant something to you.

Jackson Nieuwland is a genderqueer writer from Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Their poetry has appeared in a number of journals, in print and online.

Compound Press page