Starling is a go-to online poetry space for writers under 25: wide-ranging in form, voice, subject matter, mood. It’s vibrant, essential reading. Plus there’s the bonus of a featured writer (latest issue is Sophie van Waardenberg). To celebrate the tenth anniversary and the selection of two new editors, I invited the the co-founders, Louise Wallace and Francis Cooke, along with the two writers now at the editorial helm, Maddie Ballard and Tate Fountain, to select a poem from Starling‘s past decade and write a note to explore why the poem has stuck with them.

Poetry Shelf offers a bouquet of congratulations to the editors and participants, and looks forward to Starling‘s finger on the pulse of new writing.

Starling website

Starling was established in 2015 by us (Louise Wallace and Francis Cooke) as a literary journal for authors under 25 to publish their work and read writing by their peers. At the time we hoped could give space to a community of young writers that we knew were often not given their own platform in the broader Aotearoa literary landscape. Over the decade that’s followed we’ve been very fortunate to see how much the writers of Starling have taken up the journal and made it their own – it’s been more than we’d even hoped for, and we’ve been lucky to be a part of the start of the publishing career of so many incredible authors who’ve entrusted us with their work.

As we approached the ten-year mark, it seemed like the right time to hand over the reins, and so we were very happy to announce this September that Tate Fountain and Maddie Ballard would be taking over as Starling editors, ably assisted by the Starling editorial committee, currently made up of Joy Holley and Ruby Macomber. Tate, Maddie, Joy and Ruby are all past Starling writers who have now stepped into the role of shaping the journal for its next era, and we’re very excited to read the 21st issue, which they’re currently crafting, and all the issues to follow. We hope that Starling will be around for as long as young writers need it, and we can’t wait to see what’s to come.

Louise Wallace and Francis Cooke

four poems

Driving Directionless

It happens like that sometimes, stranded in the carpark in Mt Eden

Village, and your car battery is dead because you couldn’t sit

with the silence. The rain has been sweeping in from the horizon

all day, in and out, in and out, and you’re so much younger

than you thought you were. Nothing has been constant, lately, but

things must come to an end. I thought I knew that, I really thought

I did. And Circus Circus is so warm. The cheesecake sweet, and

we talk like we’re seventy. I went to a sushi train for lunch, plates

travelling around a circuit. The jumpsuit I bought was expensive,

but money is money. It was like trying on my own skin. There,

I say to my reflection, there you are. And as we approach the red

light, I don’t think about placing my foot gently on the brake. I

don’t think about switching lanes, or how my hands automatically

flip off the indicator after a turn. Instead, I think about tomorrow

and the colour of your eyes and the rising inside me. The words

stuck, gathering at the heart. How do you translate a feeling? How

do you wash yourself clean? I want to be wanted. I want to see where

we are all going to land at the end of all this. In the passenger seat, you

listen patiently. A reminder that you are not the enemy. I don’t know

who is. The sunset is so different every day. A cloud rears up in front

of my windscreen like a tidal wave, puffy, and peach-coloured, and

astounding. I want to remember, want to keep it all with me. Time

is unsteady. Today, is today and you finally noticed.

Brecon Dobbie

On Brecon Dobbie’s ‘Driving Directionless’ (from Issue 12)

The first time I read this poem I was overcome with envy! Partly because of its wonderful final line and partly because of how well it does sincerity, a quality I think it’s really hard to write well. I love that it’s about being a new driver in Tāmaki. I love that it mentions the cheesecake at Circus Circus. I really love that it couches its existential moments (‘How do you translate a feeling? How / / do you wash yourself clean?’; ‘you’re so much younger / / than you thought you were’) amid sushi trains and car batteries. Isn’t that exactly how life is? All the big things squeezed up against the little ones.

I’ve returned to this poem several times over the years because I love the speaker’s voice so much: wise and sad and hopeful and observant of peach-coloured clouds. I hope to read lots more from Brecon in the future.

Maddie Ballard

loss

mum went to bed for months.

got up only for using bathroom with red toilet seat &

sitting on step outside pink back door, smoking,

saying i love you without her eyes.

moving truck got stuck

under opawa’s overbridge

& my baby brother was born

just a red mess onto a matted towel.

one of those things

no one talked about.

family came to visit.

nana picked me up from school,

aunty slept, floor of my room,

& made a sticker chart so

i could be Good.

in doorways i stood

peering around corners to see

mum’s supine form or curve

of her spine as she sat outside, puffing.

her room seemed grey

i wanted to say:

what did i do?

but more than anything

i wanted to lose my first tooth;

to have a broken grin;

to tongue empty space.

mum got better suddenly –

woke up one day

& darkness had gone away,

ran out to lawn in her underpants,

cheering & dancing.

i lost a tooth eventually

& then, oh,

so much more.

Hebe Kearney

On Hebe Kearney’s ‘loss’ ‘(from Issue 15)

I am a huge fan of ‘quiet poems’ and Hebe Kearney is very good at them. I think they are the hardest poems to get right, and it’s also hard for them to jostle for space in a journal selection process, up against loud, funny, bold poems. But when quiet poems work, they sing – like Hebe’s piece here.

First up, if you’re looking for an example of ‘show, don’t tell’, the line “saying i love you without her eyes” hits that mark perfectly. We understand that something is off, there’s something distant about the mother – the reason she’s gone to bed “for months” – without the poet needing to spell the specifics of the situation out. I can see the “supine form or curve of her spine” as I read – Hebe offers those shapes to me.

Towards the end, things become brighter – the mother seems to miraculously recover and the speaker loses a tooth just as she had hoped – which makes the uppercut of the last two lines hit even harder. We remember the title, ‘Loss’, and feel that emotional impact at the end.

Louise Wallace

Any Machine Can Be a Smoke Machine If You Use

It Wrong Enough

Circe likes to live comfortably. The island,

the private jet – does putting everyone else

between Scylla & Charybdis make this

worth less? Hardly. Circe is moulding you

in her fingers like soft wax – here, amorphous

child of Morpheus, are you comfortable? Circe

takes her tax, she is a circular saw coaxing sap from a slack veiny tree

& in her menagerie the sad lion is left to starve & chew

his stately mane for comfort. She will destroy your planet

to live comfortably, but oh! she is compelling –

for instance, she claims she’s only anti-vaccination

insofar as she is against the continuation of the existence

of this human race, the world’s worst disease, abominations

bombing nations, laughing lesions of senseless flesh celebrating

their own unsubtlety, the syrupy pus of which

she collects in a glass & holds to her lips. Bemused charmer

of every snake, she has taken men to space and yet has not succeeded

in getting them to respect it. She has fought a thousand wars for you

and your right to say that war is bad, although there is a comfort in it.

Knowing who your enemy is. Circe leaves a thick slick of spit

on the panther’s taut haunch, sends him off with a resounding slap

and when his whispering ear is gone she advises you sincerely

to cultivate your loneliness, make your silence

violent, remember a woman’s first blood doesn’t come

from between her legs but from biting her tongue. Circe says

to treat comfort ephemerally, like a fleecy faery-circle

of ringworm on the skin of your inner thigh, a sick unscratchable itch

you don’t want to show. If you admit that you need something that badly

then it can be taken away from you. Circe instructs you to become blood

diamond, smoky topaz, hard-edged undesiring object of destructiveness

& self-destruction internalised by all as desire, as comfort, as Circe’s white

dandelion-floss cat who flows down the street on his way to eat

or sleep or fornicate with the mouse he doesn’t keep at home

instead silently stealing out to play with her

garnet heart among the liquorice-scented ferns.

Rebecca Hawkes

On Rebecca Hawkes’ ‘Any Machine Can Be a Smoke Machine If

You Use It Wrong Enough’ (from Issue 1)

Sometime in 2015, Ashleigh Young wrote on twitter (this was back when twitter was, mostly, good) ‘One of my students has written a poem called ANY MACHINE CAN BE A SMOKE MACHINE IF YOU USE IT WRONG ENOUGH. It’s great.’ I remember reading it and thinking that I’d love to read it someday. A few months later, going through the pieces we’d received for the first issue of Starling – I remember the day exactly, it was 14 November and I was reading submissions before heading out for the second ever LitCrawl – I picked up a set of poems by a writer named Rebecca Hawkes, and there it was.

One of the best parts of editing Starling are the moments where you get absolutely smacked in the face discovering brilliant writing by someone who, until that moment, you’ve never heard of, and realise ‘oh, wait, we’re going to get to publish this?’. Rebecca’s poem was one of the first of many moments like that – I remember reading ‘Any Machine….’ and being blown away by how expansive and luxurious it was in its language, heightened and apocalyptic while still undercutting itself at the right moments with a pitch-black humour (Circe stating that “she’s only anti-vaccination / insofar as she is against the continuation of the existence / of this human race” is a particular stand-out).

Rebecca’s poem has a lot of the themes that she’s fleshed out further in her writing since, as she’s become one of my favourite poets working in Aotearoa – a merging of classical themes and very distinctly New Zealand pastoral imagery, a very physical and sensuous love of the natural world while also being enmeshed in our modern, technology-driven present. She’s throwing it all into the pot here, and I’m sure if she looks back on this early piece now there are things she might want to change or edit out, but I hope she still recognises that at the heart of the poem is a true show-stopping line – “remember a woman’s first blood doesn’t come / from between her legs but from biting her tongue” – that still hits home a decade later. It’s been a privilege to get to follow Rebecca’s writing, and the work of so many other great authors who published some of their first writing with us, since I first read this poem, and it’ll always be a special one for me because of that.

Francis Cooke

Extract from ‘UNTITLED’ by Matthew Whiteman

for complete poem, visit here

On Matthew Whiteman’s ‘UNTITLED’ (Starling, Issue 17)

To highlight any single Starling poem from the past ten years is a daunting task. I vividly remember so many poems that struck and compelled me in my early days as a reader and contributor to the journal: Aimee-Jane Anderson-O’Connor’s ‘(Instructions)’ in Issue 6; jane tabu daphne’s ‘K–A–R–O’ and Van Mei’s ‘On Beauty’ in Issue 7; Sinead Overbye’s ‘The River’ in Issue 10 (to name only a few!). Likewise, I could list off countless poems that have made me put a hand to my heart, or pump my fist, or cheer while reading submissions during my time on the editorial committee. One of the great gifts of Starling is the range of work and of stylistic and poetic approaches that we get to read twice a year – no better job.

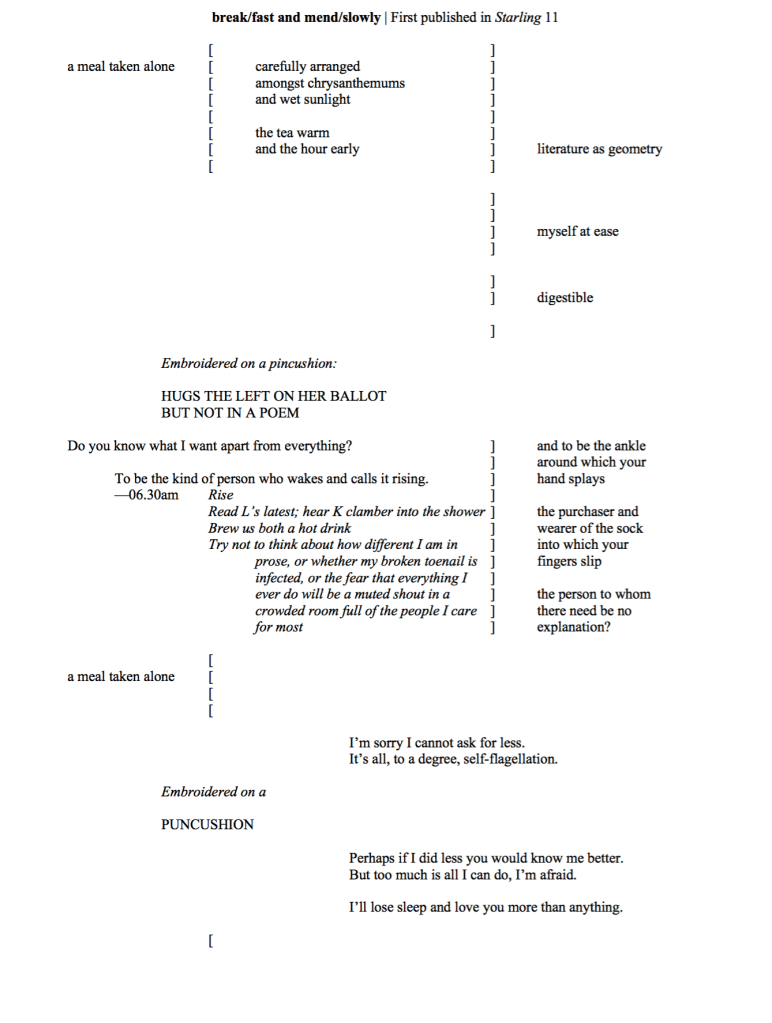

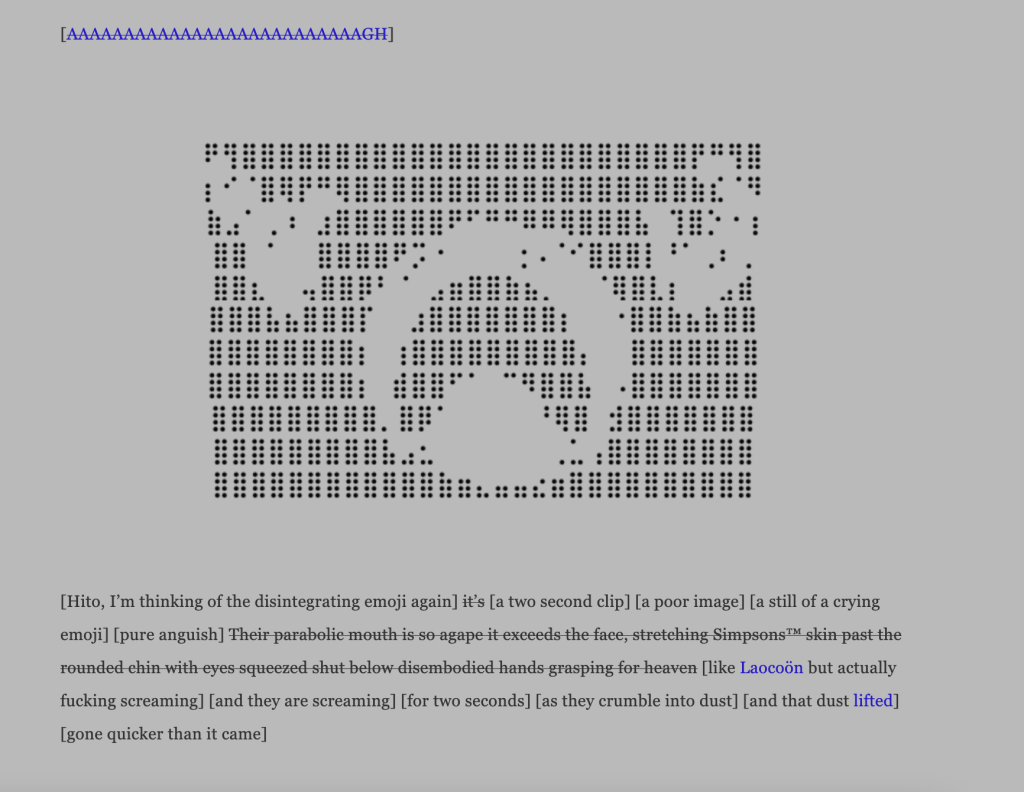

On this occasion, I’d like to spotlight Matthew Whiteman’s ‘Untitled’ from Issue 17. Dedicated to German artist, filmmaker, and writer Hito Steyerl – addressed directly to, and referencing,her throughout – this is a go-for-broke, abundant, ekphrastic, pointedly intertextual poem that grabbed me immediately on the first read. Framed within an illustrated and progressively disintegrating – well – ‘disintegrating emoji’, Whiteman contextualises this ‘two second clip’, this ‘poor image’, and its silent or elongated variations, within a larger relational and arthistorical web: Steyerl’s ‘How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File’ (2013), the iconic classical statue group of Laocoön and his sons; even The Simpsons, briefly, gets a look in. We are all scaffolded by our references, clear or opaque, and what I am so drawn to about this poem is that, stacked up and arranged in this form, it really could have only come from one person.

Matthew’s ‘Untitled’ seems to bend so many poetic conventions: the fact of the title, intentionally ‘Untitled’ or else by necessity, speaks so well to the perhaps-futile search for meaning outlined in the poem itself. ‘I want to tell you what it means,’ he writes, ‘but I’m not sure I even know, Hito.’ The arrangement of the text, in square brackets and struck-through, likewise reflects this: everything is couched in erasure, something hiding even as it’s visible, or drawing from the form of emojis as textualised (as Matthew points out, ‘[‘disintegrating emoji gif’]’). The closest we get to the text outright engaging with its meaning is within the collage of this framing. It’s perhaps not an ‘easy’ read, but one that allows a few different paths for engagement, a few methods by or levels at which it might be read. (The links! The gorgeous electric blue links to give you the chance to experience the full web Matthew is pulling from!)

I can get quite defensive of visual poetry – I never want people to think the ‘conceit’ or aesthetic identity of an effective poem nullifies or overpowers its content at line level. (In the same vein, I’m not overly interested in internet poems for internet poems’ sake; there needs to be something that grounds or further substantialises the work.) Any form can be a great act of assemblage, but the writing still has to stand out. And that’s something I love so much about this poem – that even if you stripped away all the rest of the work it’s doing, there would still be descriptions like ‘a poor image’, ‘pure anguish’, a ‘parabolic mouth is so agape it exceeds the face’, ‘disembodied hands grasping for heaven’. You would still have the immediate internal assonance of ‘Simpsons™ skin’ and ‘rounded chin’, the inbuilt, square-bracketed/struck-through pace shift of ‘[it bothers me] that lost scream [because that felt real] [wasn’t it] [someone’s scream] that then [became image] then [language]’. You would still have the closing lines to settle any of the destabilisation of what’s come before; the calm (characteristically struck-through, occasionally bracketed and linked) sentence function: ‘On Twitter [X] people just signal it like that. I want to tell you what it means but I’m not sure I even know, Hito. I think it may be a kind of speechlessness, the kind that calls you offscreen. I think you follow the scream elsewhere.’

I just love this poem. I’m drawn to its singularity, its stretching of form, its tone and the inherent line-toe of sincerity in a broadly comedic set-up; I’m compelled by its finding of art everywhere, its determination of meaning and its existential search, its deep thought. I feel really honoured, too, that it found its way to Starling and that we had the chance to publish it, especially as part of a longer intertextual poetic/artistic sequence within Issue 17.

Tate Fountain