Photo credit: Ebony Lamb

although the flighty vampires suckling so obscenely

are the only creatures that really belong in this scene

not the dogs or the willows or the girl

or the gorse with its raptures of yellow

that invasive stellation annexing the slopes

to wrestle black beech at the bush boundary

the smells of pollinated combat mingling by the water

sultry as marzipan and honeydew casting a heady spell

over the colonised valley the weeds like her very presence here

a legacy of other people’s blood and money

though she has yet to understand this history is her own

still finding a place in her bones let alone the land

from ‘Noonday gorsebloom’

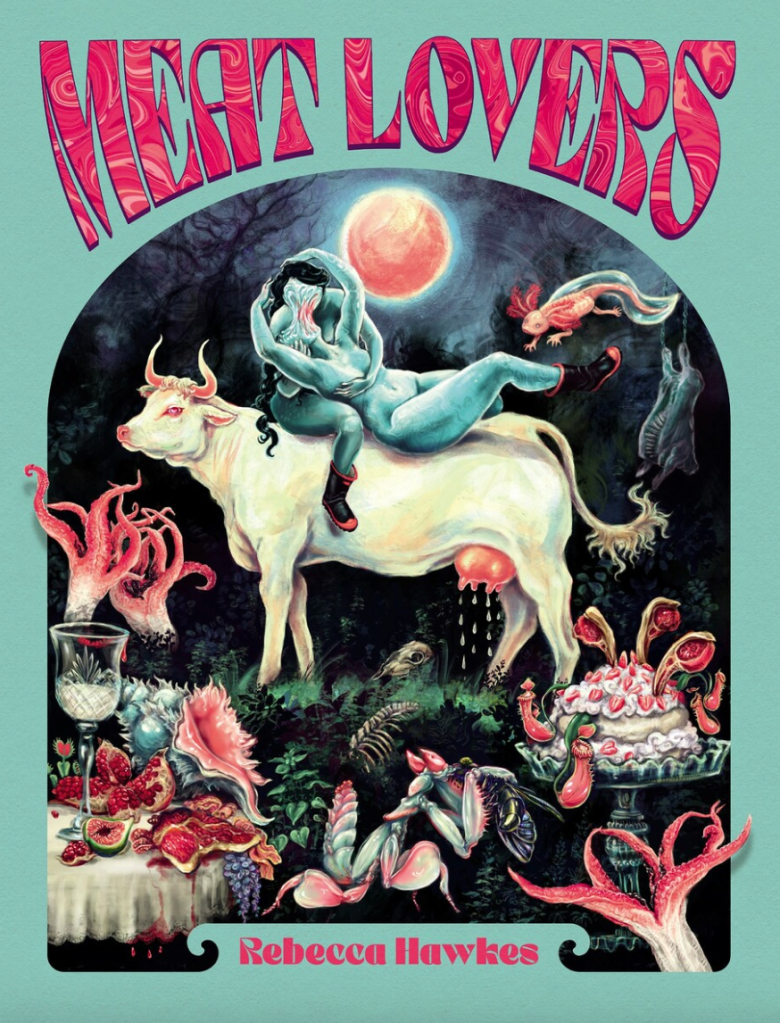

Rebecca Hawkes caught my attention in AUP New Poets 5 (Anna Jackson’s reboot of the series). I became an instant and avid fan. Rebecca’s debut full collection Meat Lovers is now out in the world and is attracting a solar system of love. Freya Daly Sadgrove wrote this for the blurb: ‘Rebecca Hawkes is the unmatched empress of viscera. Thrillingly, perverse, utterly compelling – you eat these poems like overripe peaches, or your own tongue.’

To celebrate poetry, and the arrival of Meat Lovers, Rebecca and I have an ongoing email conversation over the past month or so.

Paula: Before we discuss your sublime debut collection, these are strange and challenging times. I am finding books help. Writing helps. I just read Rachel O’Neill’s stunning Requiem for a Fruit and it was such an uplift. Inspiring. Have you read any books lately that have stuck with you?

Rebecca: Lately I’ve been disappearing into gaming a fair amount -dystopian epic sequel Horizon Forbidden West just came out and I’ve been abandoning our world for the tragic beauty of that story. I’ve also been reading a lot, enjoying the first releases in the bounty of local poetry arriving this year. The Surgeon’s Brain by Oscar Upperton stuck in my craw, as an incisive testament to an extraordinary life. It’s a powerful reminder of the ongoing need for rediscovery of queer history, and how we continue to fight for our place in the record. It inhabits the character of James Barry, a brilliant transgender military surgeon in the 1800s. Oscar’s work is precise and immersive – it felt like being dropped right into Barry’s whirring mind at various moments throughout his storied life. Reading the book is like speedrunning a novelised biography in a way that fits my fractured attention span, while also having plenty of room to breathe with Barry through his gnarliest thoughts.

I’ve also just read Chris Tse’s much anticipated Super Model Minority. Rainbows and rage, passion and pride, it meets my pent-up energy in the pandemic. This book evolves Chris’ previous work reckoning with racist and homophobic violence, and the radical possibilities of joy in a doomscroller’s world.

I’ve also been lucky to receive a copy of I got you babe, the first publication by new publishing collective Taraheke/Bushlawyer. I’m so glad to see this in the world. I got you babe includes poems and essays by the five writers, holding their power and care and grief. Importantly, it places the forthcoming anthology No Other Place To Stand (which I’ve been co-editing with essa, Erik and Jordan for the past few years), in a richer, wider ecosystem of critical and creative work around climate, capitalism and colonisation. As we get closer to the anthology launching at last (it has gone to print!), it’s daunting how little has changed since the start of this project and the pandemic – the poems sent to us in 2020 have only become more (alarmingly) prescient. The critical urgency of I got you babe is a breath of fresh air.

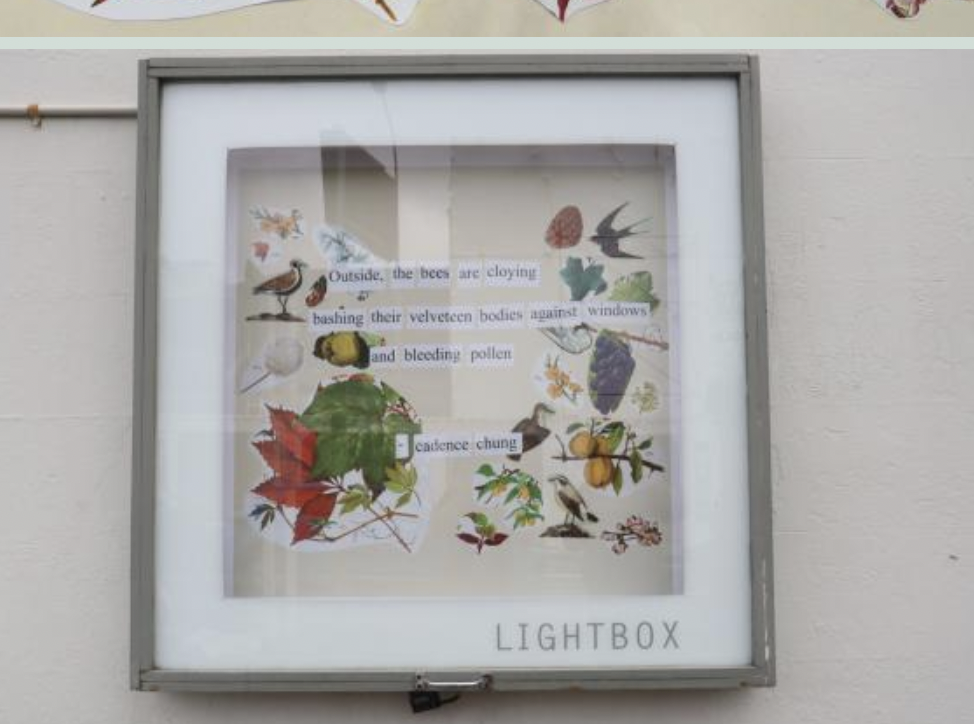

2022 is, despite all the overall horribleness of Current Events, set to be a killer year for poetry. I’m eager for the new books by Anahera Gildea, Michaela Keeble, Anne-Marie Te Whiu, Erik Kennedy, Jordan Hamel, essa may ranapiri, Cadence Chung, Khadro Mohamed, Michael Steven… My bundle from Titus Books just arrived and I’m reading Chris Holdaway’s Gorse Poems tonight!

Meatlovers Rebecca Hawkes, Auckland University Press, 2022

Paula: How was it, writing your sublime Meat Lovers?

Rebecca: Well, I’ve been working towards Meat Lovers for some while. After Softcore coldsores came out in AUP New Poets 5 in 2019, I wanted to do more with some of the down-home-on-the-farm poems, and build a more cohesive full-length collection set firmly in the rural gothic. The title Meat Lovers came early on. It led to the eventual bisected structure of the book, the two halves of one cracked geode. But getting there was a meandering process…

I bloody love to write a poem, any poem, as a wry joke or full-throated cry. The puzzle and thrill of tinkering with verse ‘til it moves on its own steam and I get to watch the poem skitter off in its own chosen direction is reason enough to keep writing them. And each poem is only one weeny little fragment in the churning vortex / hot mess of whatever’s going on in my head, so a lot of them live in completely different parts of my world that would never touch outside of a word document. A lot of poems therefore ended up on the cutting-room floor for this manuscript, as I had to corral a more cohesive set of little machines that could work as a pack for a more focused sequence. I had so many ‘spare’ poems that there were more than enough for another rather different manuscript – which in a funny turn of events was a runner-up in the Kathleen Grattan Award at OUP last year. Maybe I could have published that altogether more playful and girl-gamerish book first instead, but Meat Lovers holds the work I was most compelled to delve into, mining some darker recesses of my home and heart, and way to still live in some places from my past that I can never really return to.

Once I’d gold-panned for the vibes/themes of this book (food, farming, foolish love) and gathered my first set of poems, structuring it was the challenge – I’d never tried to be so purposeful in a manuscript order before this. I’m grateful for the early eyes of friends like Rebecca K Reilly and essa ranapiri who helped me zero in on what really mattered for the shape of this work. And then of course I kept on writing fresh poems and trying to find places for the new darlings, even as the manuscript really needed to be pruned. How has writing this book been? What is it ever like to make art, to do something freeing but also serious, disarmingly ironic but nonetheless excruciatingly sincere? At turns it has been deep work and easy fun, therapy and tomfoolery, surfing the ecstasy of creation or gruelling arduous labour. Writing the book was humbling, cos making art always kicks my ass, but obviously it’s me doing the kicking as well as my buttcheek with the boot print on it.

‘Frenzy’, Rebecca Hawkes, 2021

Paula: Love the idea that incongruous things in the world co-exist in the neighbourhood of the page! And love how we can never pin the writing process down to one easy answer. Yet for me it is the best thing in this wild and challenging and complicated world. Energy boosting. Heart easing. Body uplifting. Whether reading or writing. I get a similar reaction when I look at your paintings. I have lived with an artist for over thirty years and we inhabit a shared space, but also private and utterly necessarily separate spaces each day. How is it for you both painting and writing? Reading your poems and sinking into your art it is a yin and yang experience for me – the one electrified by the other.

Rebecca: For me the painterly and poetic forms are so intertwined, you could never ask me to choose one, or to go without them. That was why it was so important to me to do my own cover art, even if digital painting isn’t my main medium… and even though what I mostly see in my own paintings is how much learning I still have to do! My necessary poetry-space is laptop-sized and portable, so it’s a more readily accessible art than the ritual of setting up paints and solvents, and then cleaning brushes when I’m bleary-eyed past my bedtime. Sometimes I go months without having – or making – time to paint. But I somehow find the hours when exhibitions are coming up, like right now …

When I’m not both writing and painting I’m not my whole self. They’re things I’ve always done. As a child I constantly drew chimeras, collaging together the most interesting limbs from my gen 1 and 2 Pokémon handbooks and the dinosaurs I was obsessed with – an Arcanine head and mane on a Houndoom’s punk pup frame, equipped with the wings of a Charizard and an Ankylosaurus club tail for bashing. What’s it called when you’re a horse girl but for dragons? I was that. For me a dragon is still the ideal animal, an impossible assemblage of apex attributes, wise and prideful and wild… While my art subjects are often less creaturely now, dragon-building is still basically how I approach both paintings and poems. I rip little shreds of potent detail out of life or dreams, and solder them together to make something that has its own new roar.

Painting is where I most keenly feel the gap between the work I aspire to make and the limits of my capability. I’m not a planner, working out decent compositions in thumbnail sketches. Instead I dive right in with colour and a couple of starting images, then see what happens. Same for poetry, but with poems nobody can see the smudged under-layers lurking beneath the surface of the finished piece… Word docs are forgivingly blank behind the text, so no-one sees my orphanage of random lines, loose chimera limbs waiting to be assembled.

Right now I’m in that horrible gulf between expectation and reality where I’m blocking in a painting, waiting for images to emerge from the mess, knowing that every mistake will be baked in forever, making slapstick attempts to shield the hideous draft with my whole body when friends visit. But when I am actually at work on a painting I let go of all that shame. I get so absorbed I might forget to breathe, eat, drink, urinate – lost in flow-focus, crouched over my canvas between the TV and the couch. As you say, artists need necessary space, to focus and to dream… but I find I get by with surprisingly little of it.

When I paint I kneel on the carpet because there is no space in my apartment for a studio (see: me having feelings about this when I went to see Hilma af Klint’s stupendous body of work), and because painting is a kind of prayer activity anyway. It’s an act of faith, isn’t it, to scratch out some small artwork in response to the shabby miracle of the world? Writing is like that too, a deeply interior creative practice that requires me to be open, curious, trusting and responsive to whatever drifts up from my subconscious. Don’t get me wrong I don’t think my processes are all that spiritually glorious, or my artwork particularly accomplished, but when the going’s good it is transporting, and as I give my energy over to a work it breathes life back into me. Am I a pompous loon, indulging in surrender to my own bad art, while the signals of my partner’s PS4 controller and sounds of gamer swordplay beam through my body as he slays monsters in Elden Ring? Sure. But I can’t not do it.

In painting and poems I’m meditative and open, but also working hard in pursuit of something that mainly eludes me – but maybe I’ll get it next time, and this is what keeps me growing (I hope) as an artist. It also keeps me hungry for others’ work. Yes to everything you said about the energising and uplifting nature of sinking into others’ art! Reading outside of myself is crucial to my writing, and looking carefully at other people’s visual art is essential to my painting. Even though making my own art is a solitary act, if I was in a vacuum without others’ work to delight in and explore, I doubt I’d make much of anything. Do you feel this with poetry?

Paula: Absolutely. The sheer joy that the poetry of others gives me is immeasurable. I thrive on it. Like an extreme vitamin boost. For me, the process of writing is intimate, secret, unfathomable, but it is in debt to writing communities past and present. Thus my continued drive to keep Poetry Shelf alive. And I know the doubt, that aching gap between reality and expectation, I don’t know if it ever goes away. I don’t know if I can ever bear to be published again, aside from children’s books. Tell me about your connections to poetry communities. I am thinking of Show Ponies for a start! I asked Chris Tse if he was a social poet, a hermit poet or something in between!

Rebecca: I totally agree on writing being a personal activity but also inextricable from communities around and before us! Even the solitary work of writing is not completely alone… I’m always reading so my writing is inevitably in conversation with other people’s work, and eventually a handful of trusted first-readers who are the unfortunate recipients of my little jokes. Often my poems are elaborate jokes for my friends. I don’t mean to diminish the poetry by saying that… But my Wellington poet-pals are the people whose response most matters to me, and whose support buoys me along, people I trust completely with my beautiful dark twisted fripperies. I also tend to be most motivated to write when there’s a deadline, which is often some event where I know (or hope) people will show up. So even though I’ve written alone for most of my life, I’d characterise myself as a social poet these days, and am so grateful to be part of a lively community.

Show Ponies is its own beast – Freya is the horsepower behind that. But it reflects the creative connections that are possible in a community like ours, where people are good sports with open hearts. There’s a lot of trust involved in doing something big and silly. It’s as vulnerable and sincere as any earnest confessional poem. But a bunch of poets who aren’t afraid of looking like fools together is a powerful thing. To manifest your popstar destiny you have to commit to the bit!

Rebecca: I’ve missed in-person events dearly through the pandemic, and it feels miraculous that Chris and I got to launch our books to people live and in the flesh. I’m interested in what you said here about bearing to be published. Stacey Teague recently asked posted on Twitter I’m trying to figure out why I should try to get my manuscript published and what motivates other people to get their books published and several people have just said “so you can have a party!” which obviously is something you can just do (well, depending on relative pandemic risk) without all the work of writing and vulnerability of publishing at all. For my sins, I was one of the people who’d said ‘party’ right away. But the launch party for a book is so important to me, bringing all someone’s solitary work into a shared public sphere – where the book now exists as its own object and something that will literally belong to other people, outside of the writer’s brain and screens. Aside from getting to celebrate the launch, the meticulously considered process of putting a manuscript together and then having the book itself exist in hard-copy for real has been so rewarding. I’ve been publishing poems around the place for ages, but this first book feels so precious. It’s been a very different process from blatting out last-minute poems and has taught me so much more about this craft. But the blessing of poems is that we can do whatever we want with them, right? There is no requirement to write books, or to publish the poems in any format.

lambs explode onto the scene like popcorn

kernels such freshly detonated fluff

antigravity mammals no heart leaps higher

than the skipping lambs flocked in dozens

barely touching the ground for the joy

full fortnight in which they invent their limbs

before they settle down to their true vocation

grazing themselves into flesh factories

babies babies babies babies

the loin the chop the shank

the juicy vacuum-sealed rack

and great value barbecue meat pack

stunned slit hung bled gutted skinned

from ‘Hardcore pastorals’

Paula: Exactly! I was out on a rare road trip across the harbour bridge this morning and it felt like the route was lined with poems! Just the sensation of travelling got miniature poems roaming in my head. Who knows what I will do with them!

I reviewed Meat Lovers for Kete Books and absolutely loved it. First up I loved its music. Like I really love it like I might love a breathtaking album. Do you play a musical instrument? What music do you have on repeat at the moment?

Rebecca: Gosh this is so lovely of you to say! Alas I can’t claim to be a musician. I hammered away on the piano as a child and can mimic several convincing barn animal noises… Maybe I could have a go at being a heavy metal singer, but realistically that’s because my friends are just staggeringly supportive at karaoke.

I’m charmed by the sounds of words, which I guess is why I like lush OTT poetry – where it’s permissible to load up the adjectives just because they’re delicious, and make subtle music in that way. I truly was trying to think of Meat Lovers as a concept album, actually, with a Side A and Side B, and poems that can be heard alone but build something bigger when they’re experienced in order.

Lately I’m revving songs about sad cowboys and/or the devil. I love a broody lyric. Orville Peck, Nadine Shah, The Veils, Warren Zevon, Julia Jacklin, that sort of thing. The song I was trying to keep up with while running today was Sinnerman (Nina Simone), and the song I’m looping now to tune out and write this is called I just wanna lie in bed and drink my wine (various artists), which is a mood, and just before that it was Head alone (Julia Jacklin)

you have one job

which is to hold

this disturbingly large moth

battering the woven

basket of your fingers

every instinct whining to

close your fingers and crush it

or open your palms

set the fluttering insect loose

free your hands for other tasks

but this is your job

the having and the holding

from ‘Poem about my heart’

Paula: I also love the way your collection has heart. If I pick up a collection at the moment and it is devoid of heart it feels like a remote unreachable island. Yours mattered to me. What matters to you when you write? Does heart matter?

Rebecca: For these poems, certainly. This book is one big folded stained paper heart, clumsy and earnest. It’s anchored in my foundational love for the land I grew up on, gratitude for the life my parents gave me, and care for the animals we lived with – and also the felt complications in all those things. Then there’re my attempts to write about the frustrations and discoveries, failure and bliss of eros and romance – about which there’s nothing new to say under the sun but when has that ever stopped a poet? To be honest, usually when I write I try not to worry about whether a poem has heart. Something I’m doing as play might well turn into something true, but only if I don’t try too hard!

In both writing and reading, different modes call to me at different times, from the sentimental to disaffected… Recently I was bowled over by Frank: Sonnets by Dianne Seuss, which is an often devastating book – poems of desperation, poverty, motherhood, addiction – but often dryly funny. Just observing things, reporting without telling a reader what to feel. Her poems often have a sting in the tail that makes my guts churn, like this one. I’m drawn to gutting poems, just as I am doleful music.

In poems I’m interested in humour and irony and the sardonic, too – how the heartfelt can be reprocessed into more distanced ways of engaging with our feelings. In editing No Other Place to Stand, I was really interested in the poems that did this. The causes, effects, and injustices of climate change, colonialism and capitalism evoke big primary emotions – Fear, Anger, Grief, Hope, Etcetera – so sometimes the only way into these subjects without getting washed away by those feelings can be to approach through slant wit. Those poems have their place in the body of climate writing alongside the activist battle cries, mourning songs, and stirring polemics that they sit with in the book. Sidling away from pure emotion doesn’t imply a lack of care to me, necessarily – the poems are still being written! And the more I learn about the pressures facing our planet and peoples, the less inclined I am to believe there’s any one right way to respond in our heads and hearts. Plus the sentimental can be treacherous too – I was trying to be careful with this in writing my book, not glorifying my nostalgia or delivering undue condemnations, especially in how I speak about aspects of farming life.

it’s not real cottagecore unless you are up to the elbow in it

blindly groping down the blood-slick canal

as another contraction ripples around your knuckles

the cow is lain on her side licking a mud angel

your hand clutching at the calf’s limp hoof

head torch slipping over your brow

as you affix the chain and brace yourself

to pull and pull until an amniotic spill

when the calf’s head breaches unbreathing

still you pull and bring the whole body wetly

into the cold world you drag the whole darkness

drenched newborn around so the mother can lick

caked salts from her motionless baby

from ‘Sparkling bucolic’

Paula: So few women have returned to the farm in their poetry. I am thinking Ruth Dallas and Marty Smith. Ruth had a nostalgic yearning for rural life so wrote farm poems from her Dunedin home to make up for not being there! Marty grew up on a farm and returns to farmland in Horse with Hat. Your return is electrified by edgy realism, razor-edged fantasy, the whole glorious mash of childhood, ‘a rural gothic’. What pulled you back?

Rebecca: Can any of us grow out of our childhoods? The longer I spend away from the farm the more strongly I feel how that land, that life, has shaped me. I have loads of long-winded thoughts about how we live and work and eat and consume and produce on these colonised islands. In my poems it was important for me to write critically and lovingly about these things – to challenge the assumptions I absorbed about the ordinary/natural state of the world as a child, while also celebrating the gifts of my upbringing, the cruelly beautiful lessons and earthing sensory experiences and many ways of relating to other animals. I carry all this with me –I am never without it. I’m glad you registered that not all the book is straight reporting on my life though – there’s plenty of fantasy and fiction in there. Let poets tell lies!

I think often about Ruth Dallas’ Milking Before Dawn. And Marty’s book made an enormous impression on me – she really encouraged me not to worry too much about being macabre! Rural gothic, as you say, is where I’m most at home. And I was so blessed to journey ‘home’ to the farm through these poems, as well as honour previous selves formed in that place – the girl encountering a mythical panther, the adolescent queen of weed-killers, the teen rapt in agonies finding reasons to fight in the rampant gorse in the riverbed… And I hope some of this work rings true for other queer rural kids, farmhands with a taste for verse, or anyone else seeking poems with bloody dirt still fresh under their fingernails.

Paula: When I first held a copy of my debut collection I burst into tears. There was an overwhelming gap between the poetry in my head and the object I held. I can’t explain it. Something to do with a physical thing and a mental thing. Your collection has just been launched into the world – in a venue with friends and family! How is the book’s arrival for you?

Rebecca: Agh, the tears! The gap between the final proof PDF being sent off to print and the arrival of the first book was hardest for me. I’m always spelunking new depths in the elaborate limestone cave system of my self-doubt (though thankfully have enough robust arrogance to keep making art regardless). Downing tools was difficult because I knew that from here on, the book wouldn’t get any better. I wanted this book to have a wholeness between the art and writing and fussed over it for aaaaages. But at some point the endless incrementally different PDFs became a blur, so it was time to end my meddling. The months away were tough because it was when the book was most abstracted from me, just some soulless files in the ether that I couldn’t ever touch again.

But then receiving that first copy of the book was magic. Tearing into the courier package with my teeth in the work elevator to find this actual book, its own thing, with its own weight and colour and scent, an actual living object in the world freed of my brain and screens… My favourite part of the physical book is the inner covers, with a meaty marbling that I learned to do on a version of Photoshop Elements so ancient that I actually own the program (rather than subscribing annually to “creative cloud”, ew). The pinkness peeps out when the book is read, and radiates onto the creamy paper of the pages. I loved the book so much from first sight, and am so grateful to everyone at AUP for helping manifest it. And the urge to tinker further has ceased. I accept it for what it is, now – a polaroid snippet of part of my work. I no longer worry that it doesn’t contain everything I could ever put on the page, or that the gap between the work preserved in the book and the work I’m presently more interested in making will only get wider.

Launching with Chris was a dream come true. I admire his work so much, and it’s inspiring to see how his poetic interests have developed from book to book. As fellow Show Ponies, we both love the energy of a real crowd, especially in a space like Meow. We were on the same buzz about wanting to share a live event with our loved ones and communities. There’s something so special about Wellington’s poetry scene – the city is big enough for stuff to happen, but small enough to hold a close-knit community. I’m shriekingly aware that we are not post-pandemic and there was still risk looming over the event (not least cos we were both meant to fly to the Brisbane Writers’ Festival a few days later), but I’m glad we were able to gather, for my dearest mum and Razz to travel there, for Chris and I to thrive on costumes and theatrics, to demand that a handful of people offered us some obligatory praise, and, most importantly, to perform our dramatic recital of Dragula by Rob Zombie.

Rebecca Hawkes grew up on a sheep and beef farm near Methven and now maintains a tenuous work/work balance in Wellington city. With poems widely published in Aotearoa journals, Rebecca’s debut chapbook ‘Softcore coldsores’ was published in AUP New Poets 5 for the reignition of the series in 2019. Meat Lovers is her first full-length collection. Rebecca is an editor for literary journal Sweet Mammalian and the climate change poetry anthology No Other Place to Stand (Auckland University Press, forthcoming). She is a founding member of popstar poets’ performance posse Show Ponies and haphazard coordinator of the Pegasus Books poetry reading series.

Rebecca Hawkes website

Auckland University Press page

Ash Davida Jane reviews Meat Lovers on Nine to Noon

Paula Green review at Kete Books