I am not sure if two lists make this an annual event (so I resisted temptation to put ‘annual’ in the title!), but here are the books that have stuck with local poets and fans of poetry in the past year. Unlike most ‘best of 2014 book lists’, the invitation is to select favourite reads no matter where or when those reads were published. The only limitation—this is a poetry list.

Over summer, I will muse over the future of my two blogs. If I do decide to keep them running, I will make a few changes changes to clear space for my own writing time. One thing is certain, I can never review all NZ poetry books on this blog. I have a huge stack of books I want to review, but know I can only do a handful over the next few weeks. I guess with the scarcity of poetry reviews in New Zealand, I feel pressure to share all the wonderful writing that I discover. I would certainly be keen to post reviews and musing by other poets.

Thanks to everyone who contributed to this list at a time when we all have such busy schedules, and thanks to everyone who contributed to the blog over the past year. It wouldn’t work with out you. Thanks, too, to everyone who shared my posts on social media and who followed both this and NZ Poetry Box.

John Adams:

The Life-guard, Ian Wedde, AUP.

Stark metaphors, sustained muscular writing that disturbs. A strong surface with an underbelly that provokes contemplation and rewards reflection. The final group “Shadow stands up” successfully blends quotidian observation with humour. Stuff to savour.

Autobiography of a Marguerite, Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle, Hue & Cry Press.

The disquieting disclosures of these poems builds a unique experience of family; patterns of mother and daughter; trials of close binding. How can we be, with such context? A journey to a foreign part.

Fearing the Kynge, Bernard Brown, Foundation Press (c/o 14 Birdwood Crescent, Parnell.

A short collection around Henry VIII and those who passed through his life, sometimes more quickly than they’d wished. Beautifully illustrated, the text ranges from the hearty pun to closely worked items that reward revisiting.

Sailing Alone around the Room, Billy Collins, Random House.

This masterly collection includes unforgettable, accessible gems. I love his riff on Blues; and any poet will weep with laughter at the enacted difficulty of Paradelle.

Rosetta Allen:

Cloudboy Siobhan Harvey Otago University Press

‘When the eye was overcast,

there could be no poetry.’

If the face was made to mirror the stars, then the entire body responds to the cloudscape that is this beautiful collection of poetry called Cloudboy. Harvey herself says ‘The body is a nest alive with new song’, and I feel it as I read her perfected lines, full of ever changing details of the atmosphere between a very special son, and an obviously devoted mother. No longer a passive pass time, cloud watching has become an active search for understanding, beauty, love and courage. And I too find myself looking up, with appreciation.

One Human in Height Rachel O’Neill Hue & Cry

‘I love that Father finds the faint trace of cyanide on his ring finger just in time and chops it off.’

I found the words of O’Neill’s poetry happily settled on the page. The humility trumpets itself without fanfare. Each poem, each line containing a neatly package surprise – I a kid in the back seat of a her car, unravelling lollies, and remembering, feeling part of the scene, included and instantly befriended. I adore the rhymes in the midst of lines, the lists that are not lists, the epiphanies that pile up until you have to let some go, the meaning where there is no meaning, and I believed every bit of it – almost.

Sarah Jane Barnett:

The Lonely Nude by Emily Dobson (VUP) An extremely beautiful collection about dislocation, identity, expectation, and the body. It traces Dobson’s own experiences of leaving New Zealand, living in the US, and her return. Dobson’s poems are spare and exquisitely crafted. She’s definitely my #1 poetry crush of 2014.

Etymology by Bryan Walpert (Cinnamon Press) Even though Etymology came out in 2009, I only managed to read it this year. As the title suggests, the poems are about the way we create meaning, not only in terms of words, but in our relationships and lives. It’s so sharp and clever that it made me want to give up writing.

Curriculum Vitae by Harold Jones (Xlibris/self published) Jones’ debut collection was my surprise of the year. Generally speaking, self published collections aren’t very good. I should have known that this would be the exception when I found out Jones has been published as part of AUP New Poets 4. Curriculum Vitae is a wonderful exploration of aging, regret, and memory. It was the only collection this year that made me cry.

Airini Beautrais:

2014 has been such a fruitful year for poetry. I haven’t quite finished reading all the wonderful local books that have come out, some as recently as last week. I have loved Hinemoana Baker’s waha/mouth (VUP 2014). And Maria McMillan’s Tree Space is an amazingly assured first full-length collection (also VUP 2014).

Diana Bridge:

For me this year has been weighted towards prose. I began it with the biography of Penelope Fitzgerald, which I interleaved with a re-reading of all her novels. Her last, The Blue Flower, was recently described with insight by Alan Hollinghurst as having ” something of the overall effect of a poem, a constellation of images and ideas.”

While I am waiting for the next collection of wonderful Australian poet, Judith Beveridge, I have been reading through her last two: Wolf Notes and Storm and Honey (Giramondo, 2003 and 2009), relishing her naturalist’s eye coupled to extraordinary and sustained imaginative powers. All her poems are filled with grace and intelligence.

Now a single poem, one I had been searching for since I first read it in the New York Review (October 7, 2004): Seamus Heaney‘s ‘ What Passed at Colonus’, written in memory of Czeslaw Milosz. I would want this to be one of the last poems I ever read.

Amy Brown:

Horse with Hat, by Marty Smith (VUP, 2014): This collection is a poignant and wry family biography. It juxtaposes earthy and transcendent subjects (the racetrack, the farm, Catholicism, war) as naturally as its stunning accompanying collages (by Brendan O’Brien) do. I especially loved Smith’s horses; I can picture the ‘dawn horses’ ‘who flatten, who scatter’ perfectly.

Final Theory, by Bonny Cassidy (Giramondo, 2014): This verse novel develops an eerie, quietly filmic atmosphere of post-apocalypse. Cassidy is an Australian poet, who wrote part of this poem while travelling in New Zealand – the landscape she describes is simultaneously recognisable and alien – a place where ‘three stilled turbines balance the space like stupas’ and ‘the ocean’s a mouthed thought’. Exquisitely clear and unsettling, it is the sort of book I’d love to write one day.

Mondrian’s Flowers, By Alan Loney and Max Gimblett (Granary Books, 2002): I stumbled upon this poetic biography of Piet Mondrian while reviewing Loney and Gimblett’s recent eMailing Flowers to Mondrian. Only 41 books were made, each with rough-cut watercolour pages and an exposed primary-coloured spine. Three long poems by Loney in tribute to Mondrian are punctuated by Gimblett’s watercolours. Reading it is a meditative act; if you’re in Wellington, I recommend looking at the copy in the National Library. Her

Rachel Bush:

Marty Smith, Horse with Hat Victoria University Press Marty Smith’s work is new to me. Rural New Zealand, family stories, and the stories of a generation are combined in her excellent first volume of poetry. It’s poignant stuff that doesn’t balk at the sorts of tough, sad realities that exist in all families.

Lindsay Pope Headwinds Makaro Press Lindsay Pope’s engaging first book of poems is very timely. Family events, like the birth of a grandchild and low key domestic things like making muesli feature in it, but he’s also drawn to write about solitary lives like that of the caretaker on Stephens Island or the man in ‘Outpost’ whose closest contact with the outside world comes through the radio he operates.

Vincent O’Sullivan Us, then Victoria University Press I enjoy the ease with which Vincent O’Sullivan can refer as easily to a Dunedin Beach as he does to lines from Robert Frost or Wallace Stevens or to the poetry of McGonagall. He investigates difficult questions, but doesn’t come up with facile, tidy answers to them.. This is a collection thoughtful, witty, sure-footed poems.

Michael Harlow Sweeping the Courtyard: The selected poems of Michael Harlow Cold Hub Press

Poems chosen from seven books of poetry by Michael Harlow make for a lively and varied collection. He is interested in and sensitive to how each poem looks on the page. I enjoy his distinct and often quirky voice.

Kay Cooke:

Essential NZ Poems Facing The Empty Page selected by Siobhan Harvey, James Norcliffe and Harry Ricketts. Published by Godwit. A real treasury indeed of NZ poets. (Although I missed Tim Jones and Helen Lehendorf not being there).

Si no te hubieras ido / If only you hadn’t gone by Rogelio Gueda with translations from the Spanish by Roger Hickin and an introduction by Vincent O’Sullivan. A gem of a book with poems about distance, love and Dunedin. Published by Cold Hub Press.

You Fit The Description: The Selected Poems of Peter Olds published by Cold Hub Press. The long-awaited collection of Olds’ poetry; a prolific New Zealand poet whose background in poetry in Aotearoa stretches back to the James K. Baxter era. I’m thoroughly enjoying this book which is sure to become a classic. I haven’t finished reading it yet, but so far – It’s a cracker.

A chapbook that has both inspired and thrilled me with its re-imagined worlds within worlds, delicately traced with a steely eye, is Jenny Powell’s Trouble published by Cold Hub Press.

Ruth Arnison’s PoARTry @ Olveston (self-published) with its clever mix of paintings and words, is also a favourite from my 2014 pile of poetry.

Karen Craig:

I’m looking at the three books I’ve laid out on my table and what I notice is that they all have lots to do with the sea, seabirds, islands. And I have a wonderful feeling that if I were to pry up their covers I’d hear sounds of imaginary oceans, like when you hold a seashell up to your ear. Because, like seashells, these poets have taken the sounds of our world and clarified and amplified them, made them resonate, turned them into a deep, quiet, prolonged roar. Each with a different pitch, of course.

1. Richard Blanco Looking for The Gulf Motel, University of Pittsburgh Press 2012 (You can get it at Auckland Libraries!). Richard Blanco’s seasides are Cuba, where he was born; Florida, where as a boy he emigrated with his family; and now Maine, where he ended up for love. He sings the enigma of memory, the yearn of sorrow, the terror of romantic love. “The sea is never the same twice. Today / the waves open their lions’ mouths hungry / for the shore, and I feel the earth helpless.”

2. Michele Leggott Heartland Auckland University Press 2014. These poems burn like the hot blue stars which recur in one of them. You dive in to their mesmerising, punctuationless (as always) whirl and find at the heart a distillation of spirit that is so honest as to be unforgettable. The long poem about the introduction into her life of her guide-dog ends with the simplest of phrases, “her name is Olive”, and it’s as if a choir broke out.

3. Bob Orr Odysseus in Woolloomooloo Steele Roberts 2014. Bob Orr embraces the sacred and the profane better than anyone. From the ancient mysteries to modern gazes, from Penrose to Valparaiso, his imagery amazes me and his turns-of-phrase make me want to get down on my knees and say Hallelujah! “As the Southern Cross / salts these hours / I shiver beneath signs and wonders.”

David Eggleton:

There were a number of outstanding poetry books I read this year, but these in particular offered things which have stayed with me.

- Kay Mackenzie Cooke’s book-length sequence Born to a Red-Headed Woman (Otago University Press) offers a remarkable evocation of growing up in rural Southland: ‘The teacher draws close, / her own fingers cool, // narrow streamlined/ dragonflies that touch down/ briefly where my fingertips/ have begun to make mist, / What lovely moons you have, she says.’

- In Sweeping the Courtyard: the Selected Poems of Michael Harlow, Michael Harlow’s poems are like miniature echo-chambers, their lines teasing and entrancing with repetitions of words and phrases which resonate with subtle implications: ‘We were walking out of the park, your/ hair on fire under a full fall of moon, / the flowering almond its bridal white/ fading earlier than was remembered// I could hear, a leaf-fall of thought . . .’

- I was impressed by the restless inquisitive searching tone, the careful observation, in Jenny Powell’s small collection Trouble (Cold Hub), as in her poem describing the scene in a photograph ‘Guided Walking Party on the Franz Josef Glacier, New Zealand c. 1908’: ‘five women/ standing on/ frozen contortions of time/ frock hems damp/ from trailing overground undulations . . .’

- I was also pleasurably arrested by the precise and telling imagistic phrases that made up Hinemoana Baker’s collection waha:mouth (Victoria University Press), as for example in ‘what the whale said’: ‘ I break/ the brine, my flukes a black book// a mast in your mind/ cross of the drowned. . .’

- I was amused by the rhythms and rhymes forming sweet and sour stanza combinations in Tim Upperton’s poetry collection The Night We Ate the Baby (Haunui Press), as in ‘All the Things I Never Knew’: ‘Bobbie watches headlights move/ across the wall. / A little rain begins to fall — / a little rain to end the day. // It falls differently in L.A./ Choctaw Ridge is far away.’

- Likewise, I enjoyed the almost whispered whimsy and well-turned verses in Peter Bland’s short book Hunting Elephants (Steele Roberts), as in his dream-poem about James K. Baxter: ‘Not/ a pretty sight/ with his soup-stained beard/ but there’s a lovely/ holy glow / to his skin . . .’

- Tom Weston’s collection Only One Question (Steele Roberts) contains a number of extraordinary poems, especially about crime and punishment. He shows us characters who have the fatalism, or else the tragic destiny of Joseph Conrad’s characters, as in the title poem: ‘When he sends children to prison the parents go too, / trailing along like wind-ripped flags.’

- And, finally, I was taken with the rapping urgency of Leilani Tamu’s street-wise voice in The Art of Excavation (Anahera Press), as in ‘You’, a poem about her father: ‘. . . driving around Auckland in your crusty-as car/ a hole in your sock, an empty pocket, a heart full/ of dreams but never a cent . . .’

Laurence Fearnley:

Dylan Thomas SELECTED POEMS (Penguin Classics)

I watched a couple of science fiction/space movies recently and, in general, I found them pretty dull and really long. But, a couple of them included poems by Dylan Thomas. The film Solaris had ‘And Death Shall have No Dominion’ and Interstellar included ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night.’ So I found my copy of Dylan Thomas’s poems and I noticed in its introduction that Thomas is described as ‘dense and often difficult’. I don’t know about that. I liked the imagery in some of the poems – ‘Where birds ride like leaves…’ (When I Woke) or ‘…the shabby curtains of the skin…’ (A Process in the Weather of the Heart), for example . After reading Thomas I got out my James K Baxter and Janet Frame books and spent a while flicking back and forth between the three writers.

Joan Fleming:

I have never read anything like George Dyungayan’s Bulu Line: A West Kimberley Song Cycle (Puncher & Wattman, 2014), edited and translated by Stuart Cooke. Cooke braids a dimensional translation of an Aboriginal song-poem from many strands: the words of the song in language, traditional owners’ verbatim explanations, an ethnomusicologist’s commentary, and his own circling, cycling rendering in english. Such important work; this book is a bit of a game-changer.

Siobhan Harvey:

Alexandra Fraser, Conversations by Owl Light (Steele Roberts) is a first collection which engages with concepts of chemistry, love, botany, family, astronomy, tarot and ancestry. The author’s evocative language, pinpoint accuracy and sumptuous concern for human interaction make is a 2014 standout.

Ancestry also underpins another exciting first book, Leilani Tamu’s The Art of Excavation (Anahera Press). Excavating her family and Pacific history, the book is an entwining of legend and cultural realism.

Miriam Barr, Bullet Hole Riddle (Steele Roberts) packs a powerful punch. A triptych charting the narrator’s cruel, abusive history, it’s a book of unflinching honesty and potent impact.

Dinah Hawken:

The Great Enigma, New Collected Poems, Tomas Transtromer, New Directions Books, 2006.

This has been my favourite book for a couple of years. I’d love to be able to write like him and it would take too long to tell why.

Body English, Text and Images by Len Lye, edited by Roger Horrocks, Holloway Press, 2009.

I splashed out and bought this book a few months ago, not long after reading Roger Horrocks’ biography of Len Lye.

I knew I would love it because Lye was so extraordinary; particularly in his understanding of how the body gives rise to all creative ventures including poetry. ‘ I hold/words in the bone.’

Otari, Poems and Prose, Louise Wrightson, Otari Press, 2014.

This very new, first book by Louise Wrightson has been written slowly, close to home. Louise lives on the edge of Otari/Wilton’s Bush in Wellington and has written a book about place that is dedicated, funny and beautifully produced.

David Hill:

I’d like to mention: 1. Ruby Duby Du, by Elizabeth Smither (Cold Hub Press, PO Box 156, Lyttleton). Smither’s enchanting poems for her new grand-daughter, which manage to combine tenderness with her distinctive cool, meticulous observation.

2. A Treasury of NZ Poems for Children, ed by Paula Green, illustrated by Jenny Cooper (Random House). Yes, I know I’m not supposed to include Paula Green’s poems, but she’s just (“just”!!) the editor of this terrific anthology which ranges from Baxter to school-kids. Exuberant, engaging, educational, and made more so by Jenny Cooper’s magic illustrations.

Bill Manhire:

Do song lyrics count as poetry? If so, I’ve been enjoying The Lines Are Open from The Close Readers (aka Damien Wilkins). It includes tracks about departed writing friends like Barbara Anderson and Nigel Cox. One of them – “The Ballad of Tarzan Presley” http://theclosereaders.com/track/the-ballad-of-tarzan-presley – makes my heart hurt yet somehow leaves me happy.

It’s been a strong year for New Zealand poetry. So many accomplished first collections! I was pleased to see Frances Samuel’s Sleeping on Horseback (VUP) in print – I’ve been waiting for some version of this book for about ten years. Another impressive first book is Kerry Hines’s Young Country, in which the poet’s words keep company with the images of 19th-century photographer William Williams. It’s a mix that can seem easy and obvious, but is surprisingly hard to do well. Between them, Hines and Auckland University Press make the task seem effortless.

A couple of other great reading pleasures this year have been A Dark Dreambox of Another Kind: The Poems of Alfred Starr Hamilton (edited by Ben Estes and Alan Felsenthal, and published by The Song Cave) and Maurice Riordan’s new collection from Faber, The Water Stealer. Alfred Starr Hamilton is the poetry equivalent of the apparently naïve artist, of a Chagall or an Alfred Wallis. He has an appealing clumsiness, and specialises in astonishing small moments, as in his one-line poem “Carrot”: “I wanted to find a little yellow candlelight in the garden.” Maurice Riordan manages to be lyrical and thoughtful all at once, and is also the editor of The Finest Music: Early Irish Lyrics, a handsome anthology which includes translations from Tennyson to Riordan himself, as well as a number specially commissioned for the book.

Alice Miller:

Sam Sampson, Halcyon Ghosts (AUP, 2014)

‘shadow this, take and come up/ shadow, come to the present … the sur-/ face… the Lion —– the Light —– the Luminous’

Lee Posna, Arboretum (Compound Press, 2014)

Steven Toussaint, Fiddlehead (Compound Press, 2014)

Emma Neale:

Poetry books this year I enjoyed…. I still have many books on my bedside table that I’m still only part way through – e.g. Stefanie Lash’s Bird Murder and Hinemoana Baker’s Waha-Mouth and more and more… but of those I have finished, the memorable ones are:

Siobhan Harvey, Cloudboy – I hope it’s all right to nominate a book I edited – it’s the only one I’ll let myself name out of some other wonderful books I worked on this year – but this one stood out for the ’tensile delicacy’ with which it maintains the extended metaphor of boy and mother as shifting cloudscape; for its subtle use of line and page as physical space as well as rhythmic unit; for its music and invigorating intelligence. It is an important milestone in local publishing, I reckon, for the poise in that sustained motif; for the fact that the metaphor never feels strained or gimmicky; and for the richness of the psychology in the relationships portrayed across the developing sequence.

Alice Miller, The Limits – for its dreamy eeriness, its evocation of beauty even as it catches the jittery sense of a civilisation crumbling; for its creation of the atmosphere of dread and yet a sense of old-new mythology as well.

Michael Harlow, Sweeping the Courtyard – a selected from Harlow seems long overdue, and it’s a joy to have this now that older volumes are out of print. His sense of the surreal, the power of the subconscious, and his ear attuned to the lilt and rise of a sometimes slightly eccentric syntax shows a musical ear for how to upend where the emphasis normally falls in a line. It keeps us listening closely to the swerve and duck of words: how meaning can shimmer from one sense to another, depending on how you hold light to the line. His sense of the power of the subconscious and seems to perhaps have filtered through to a poet like Alice Miller.

Peter Olds, Selected Poems – I am a latecomer to Peter’s work, and the stretch of experience here, as well as the energetic vernacular, was both refreshing and sometimes devastating to read. Many of the poems record pushing himself right to the edge of risk, and the cost is shown to be very bleak at times – which means that the mischievous, finger-flipping humour that survives in some poems is all the more welcome.

Tim Upperton, The Night We Ate the Baby – I kept waiting for my kids to ask why I was reading this book. They never did. I enjoyed it for its technical control and its grim, self-loathing, Beckettian humour. It reminds me a little of Simon Armitage’s work: Simon Armitage meets Wendy Cope in a horror film with dialogue done by Dylan Moran? Something like that: it leaves me a happy kind of uncomfortable.

Zarah Butcher McGonnigle Autobiography of a Margeurite – I loved the concept – sometimes I loved the concept more than individual poems, but this was a bold, adventurous debut.

Cilla McQueen Edwin’s Egg and Other Poetic Novellas – witty, surprising, gracefully succinct, playful – the implied dialogue between archival image and the text was gorgeously unseating and sideways, sometimes; others, poignant, piquant, peppery, plangent.

Vivienne Plumb:

My favourite poetry read of this year was a copy of Paris Spleen by Charles Baudelaire, purchased at the wonderful Scorpio books independent bookstore, 113 Riccarton Rd, Christchurch. Originally published in 1869, this new reprint is from Alma Classics Ltd, U.K. (2010). These pieces by Baudelaire are considered to be very early prose poems.

Baudelaire wrote that ‘Parisian life is rich in poetic, marvellous subjects’, and described in a letter of 1862 his ambition to make the pieces that were eventually dubbed ‘prose poems’.

Excellent!

Lindsay Pope:

Leaf-Huts and Snow-Houses by Olav H. Hauge. Pat White introduced me to this Norwegian poet. He lived nearly all his life in his native Ulvik where he worked as a gardener. His writing is simple and precise yet laced with a lot of wisdom.

Lindsay Rabbitt:

Odysseus in Woolloomooloo, by Bob Orr (Steele Roberts, 2014), 60 pp., $19.99

‘If James Joyce could reanimate Ulysses [Odysseus] on the banks of the Liffey, why not bring the wily old wanderer to the South Pacific?’ Iain Sharp posits in his review of Odysseus in Woolloomooloo (a harbour-side Sydney suburb) in the July edition of Landfall Review Online, which I tout as my favourite review of a NZ poetry book, coincidentally on my favourite NZ poetry book (that I’ve read) published 2014. I have five of Bob Orr’s eight books of verse in my bookcase, including his first, the scarce-as-hen’s-teeth Blue Footpaths, published by The Amphedesma Press out of London in 1971, and this beautifully-produced latest offering sees Orr, a boatman on the Waitemata Harbour, and one of our finest lyric poets, at the top of his game, whether retracing his boyhood homeland in rural Waikato, or recalling his Wellington days, or visiting a terminally-ill friend in Sydney, or wandering the streets of Auckland, or out night fishing: ‘As the Southern Cross / salts these hours / I shiver beneath signs and wonders.’

Jack Ross:

Char, René. Furor and Mystery & Other Writings. Trans. Mary Ann Caws & Nancy Kline. 1992. Introduction by Sandra Bermann. Foreword by Marie-Claude Char. Black Widow Press Translation Series. Black Widow Press. Boston. MA: Commonwealth Books, Inc., 2010.

This is a big, generous dual-text selection of a lot of work form the whole span of René Char’s career, from early surrealist days, though the darkness of the Vichy years in France, and into postwar existentialism and disillusionment. Char was one of Paul Celan’s favourite poets, and a close personal friend, and the affinities between the two poets are quite striking — though probably more in the mood and underlying seriousness than the surface texture of their work.

I’ve also been reading a lot of NZ poetry books this year for Poetry NZ. I tried to say something about each of them at the back of the latest issue, but you can link to the detail of my remarks.

Lisa Samuels:

A few poetry books I found in 2014, with room for more

Iain Britton, Photosynthesis (Kilmog Press 2014). A beautifully hand-made art book in 40 copies, with 20 poems that attend to the medial line between the conscious report of observed and felt phenomena and the image moment that swerves the mind.

Jill Magi, Labor (Nightboat 2014). An essay in poetry, framed as a workography, that lays bare the devastated internal landscape of university labor. The university lecturer must strain the bad faith of corporate academia through her body in order to try and make a good faith realm for students and ideas.

Alan Halsey, Rampant Inertia (Shearsman 2014). From asemic (and glossed) clinamen to translingualism to talking places, this book has a world-attending and word-spelunking energy I crave in poetry.

Stephanie Anderson, In the key of those who can no longer organize their environments (Horseless Press 2013). Call it cento, source work, or reassembled appropriation, this book knows how to balance its languages in a vibrant sonic think-space for social thought and bodies in peril and houses and history.

Doc Drumheller, 10 x (10 + -10) = 0 (The Republic of Oma Rapeti Press 2014). A complex and delightful document of lingual devotion and social mixing. Drumheller has assembled his 10 pamphlets produced over 10 years to make helixes of anagrams and energetic rhymes. The poet as seer and Shakespearean “fool” for cultural attention.

Sam Sampson:

This year I’ve been revisiting Keith Waldrop’s Transcendental Studies: A Trilogy (University of California Press, 2009). When first opening the book I was drawn to his use of collaged lines and the effortless sway between the personal and metaphysical. The topology, or bricolage of purloined texts adds to the rich texture and music of his poems. He suggested in a recent interview, that poetry is ‘having nothing to say, and saying it,’ explaining, he was more interested in a sense of music, than the drive towards a philosophic, or information based poetics.

I’ve also had the pleasure of reading two recent volumes from the American publisher Black Ocean: Zach Savich’s Century Swept Brutal, and Elisa Gabbert’s The Self Unstable.

At the local level, I really enjoyed Alice Miller’s collection The Limits (Auckland University Press, 2014), with its elliptical and economical syntax. The imagery is deceptively refractive, and (as Barbara Guest suggests), at its best, a circling, or delimitation of the frame extends the line beyond the page.

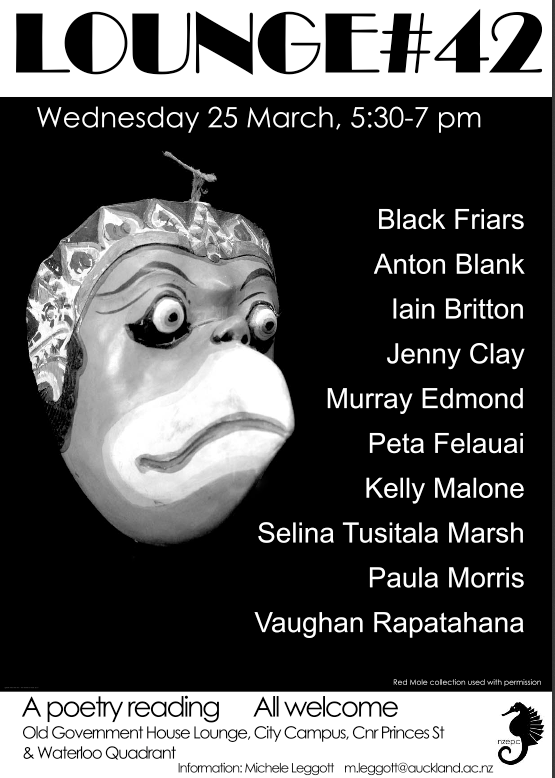

The second discovery was an event I was involved in for the New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre (nzepc) LOUNGE #41, where the NZ based American poet Steven Toussaint read. His rhythms contain a remarkable subtlety, an unmistakable momentum of word and thing (word-ling). There are a number of his poems online, or you could search out his chapbook Fiddlehead (Compound Press, 2014).

Iain Sharp:

I was pleased to see Alan Brunton’s Beyond the Ohlala Mountains topping The Listener’s belated list of 2014 poetry books. With its breadth of vision, wit and musicality it tops my list too, but I’d also like to draw attention to a couple of Auckland University publications that The Listener did not mention.

Sam Sampson’s second book Halcyon Days is the brainiest local poetry, I reckon, since the untimely demise of Leigh Davis. Yes, it’s challenging work, but the reward is in peeling back the layers and discovering the care with which Sampson has chosen each phrase.

Kerry Hines’s debut, Young Country, not only pays tribute to (and reproduces some of the fascinating images of) the great underrated New Zealand photographer William Williams but also opens up new approaches to writing about our colonial past.

Marty Smith:

waha/mouth Hinemoana Baker (Victoria University Press)

is breathtakingly, cracklingly alive. It should be read with a de-fibrillator. I get breath loss and my heart-beat jumps when the poems go leading into unexploded places, then all over again with wrenching images, like Tinkerbell

‘ I turn from black to white inside

my own limbs. Who makes this howl, whose

hindquarters drag like a bag of coal?’

Raw relationships are opened up, as in the itching madness of ‘Malady,’ and ‘running’ pulls me breathless

and still you caught me grabbed

my arm my clothes my woollen jersey unravelled as you

pulled until there was a thin gray thread

getting longer between us and the faster I ran

the colder I got

and the travelling sadness of this:

I miss you, It’s like a cave in this mouth.

It’s a terrible saxophone solo.

Read the back cover. I’d like to think that I read this book with a candle guttering in my mouth the whole way.

Bird murder Stefanie Lash

I’m completely besotted. The first place I love it is the sound echo in the title, but really the first place I love it is the little embedded crime sticker. You can’t peel it off, can’t get away from it, because this is a post-colonial protest at the fate of the Huia. I have to admit to a nostalgia for the world of my great-aunt and my grandmother, who were full Victorian Gothic, so I might be a suspect judge. But my fascination really comes from the twisty linguistic inventiveness. I love how the protest is laid out in the conventions of a traditional murder mystery, but full of flavour in an amped up version of this genre. And yet, not. It’s laid out in lush and hallucinatory images, in gorgeous language. Look at this murder scene –

‘the man is grey, and a shining black concave meniscus

of blood has formed, like oil on water,

where he has dropped his whiskey glass

and the characters are absolutely skewered:

Mrs Cockatrice is rosy, lucent:

her guests, enchanted.

Mrs Teck’s lips peel off her teeth

in a real storm of delight.

Mr Cockatrice, always sheepish,

always just on the brink of a toast.

Not saying anything about the huia, that pleasure shall be left untouched for the reader. I will say, what a feat, to keep to the form so that the narrative feeds its own texture into the whole drama. I just love it.

Tree Space Maria McMillan

I love how these poems are experiments with hushes and stops and gaps, so when I read it I get a sense of space, of joy in the richly observed world, in its breathing biology, as it were, in the stops of sadness which are a powerful reminder of what we must do to keep it.

‘The ocean is never

the same twice. You don’t know if you’ll open the door

on yellow fish flicking past, or a swarm of jellyfish little

fisted stomachs pulsing

I love how the poems sharply enact the sensations of their worlds, so the smell of the bush floor rises up in Tree Space

In the dark birds are heavier and we can hear the small valleys of

their footfalls.

It’s true that death and life smell the same here

so it gives me a slight creeping dread, but then it moves straight to ‘leap like a sugar glider’.

I love how the intricacies of scientific wonder carry such a pure joy

Joe tells me the flagella

in these new colonies

is trapped inside

so each daughter

makes a tiny hole in herself

and pushes her whole self through,

turns herself right side out

the opposite of the observations of our collective humanity –

‘ The kingdoms of life are often revised.

Humans are closer than turtles to dinosaurs.

Truth had two legs before it had four.

And I love how deceptively simple the cover is, itself anchored but floating. I happen to know Maria has knitted gloves of this cover.

Elizabeth Smither:

‘I am a poet who is a woman, not a woman poet’ Ruth Fainlight has said. I dip into her New and Collected Poems (Bloodaxe, 2010) every year for a voice that is warm and wise and tough. Last Christmas she sent me a card designed by her photographer son: stone angels in flight over a cemetery. I love to think of her wild dead brother, Harry, threatening to burn down the offices of Faber & Faber if they didn’t return the poems of his they were going to publish.

Chris Tse:

I’d like to name two books and one poetic curios that have reminded me this year of the possibilities and joy that poetry can bring. Reading them was like surveying a city from the top of a skyscraper – there’s a sense of wonderment mixed with danger as you grapple with a dizzying and unfamiliar view of the familiar. All three are daring, inventive bodies of work that reveal and give so much more with subsequent readings – the hallmark of all great poetry:

Bird Murder by Stefanie Lash (Mākaro Press, 2014)

Autobiography of a Marguerite by Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle (Hue & Cry Press, 2014)

Pen Pal by Sugar Magnolia Wilson (Cats & Spaghetti Press, 2014)

Reina Whaitiri:

A Treasury of NZ Poems for Children published by Random House New Zealand.

This is a beautifully produced book. Everything works really well. The illustrations are absolutely delightful and will bring pleasure to any child, young or old. The poems themselves cover such a wide range of topics and they too will delight.

Dark Sparring by Selina Tusitala Marsh and published by AUP.

There is such a wealth of wisdom and profound insight in the poems presented here.

The CD included is an extra bonus and reminds us that poetry should be heard and not

only read quietly to one’s self.

Puna Wai Korero published by AUP.

The poems in this anthology reveal some deep-seated resentments and longings as well

as heart-felt love and desire. They offer insights into the hearts and minds of Maori, some living today and some who have passed on.

Kirsti Whalen:

Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood Penguin, New York

A strange, beautiful navigation of a feminist dreamscape. Hilarious and moving in equal measure.

Bullet Hole Riddle by Miriam Barr Steele Roberts

The most arresting modern poetry collection I may have ever read, tackling abuse and consent with lyrical command.

Castaly by Ian Wedde AUP

This collection predates me but I loved the challenge of it: the longer poems casting out in exploration and the shorter acutely observed.

A History of Silence Carrie Rudzinski Self published

Rudzinski generally performs her work, but her words sing equally vibrantly from the page. This book is much like going on a road trip with someone you love, while questioning everything.

Sue Wootton:

Here my poetry picks for 2014. Comments for these first two are taken from my fuller reviews which appear in Takahe 82 and 83.

Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle Autobiography of a Marguerite Auckland: Hue & Cry Press (2014).

This book-length poetic narrative speaks powerfully to the claustrophobic effect of chronic illness: the endless burrowing for meaning, the constant search for a sense of order, the fleeting glimpses of certainty which dissolve as soon as they’re probed. The usual orientation measures no longer apply: “Outside there is no weather…my watch has stopped.” Butcher-McGunnigle’s writing goes to the aching heart of disconnection and of longing for repair.

Janis Freegard The Continuing Adventures of Alice Spider by. USA: Anomalous Press (2013). Alice is frank and tart (actually “she’s a trollopy little tart”). She sets traps with words and makes you wriggle like heck when you get caught. Alice Works ought to be pinned above every writer’s desk. It tells what happens when Alice gets a real job. After a while Alice concludes: “Work is the sale of strength, of thought, of dexterity. Alice takes up writing. She sells her soul.”

Also: I have really enjoyed these 3 collections: Si no te hubieras ido/If only you hadn’t gone by Rogelio Guedea (with superb translations by Roger Hickin), Cold Hub Press 2014. A poetic sequence about absence, yearning, solitude and love: “I know you’re asleep while I’m writing this,/ there on the other side of the world, / that’s why I do it, just to see if we might bump into each other / in some corner of your dreams: otra vez.”

Parallel by Jillian Sullivan, Steele Roberts 2014. A collection which examines the warp, weft and weave of family, developed from the manuscript which won Sullivan the 2011 Kathleen Grattan award for a sequence of poetry: “how every kind of death we don’t desire / hangs like a mask above our stories, above our vows.”

Edwin’s Egg &other poetic novellas by Cilla McQueen, Otago University Press, 2014. What’s not to love here? This wee box, opened, spills pure delight: “The more the imagination grasps at the idea the greater the void created.” Also: “The scones are satisfying.”