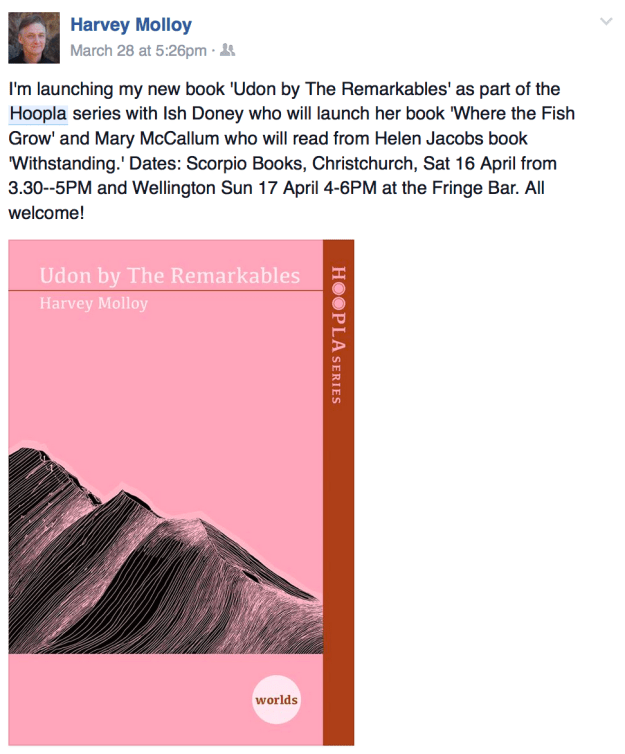

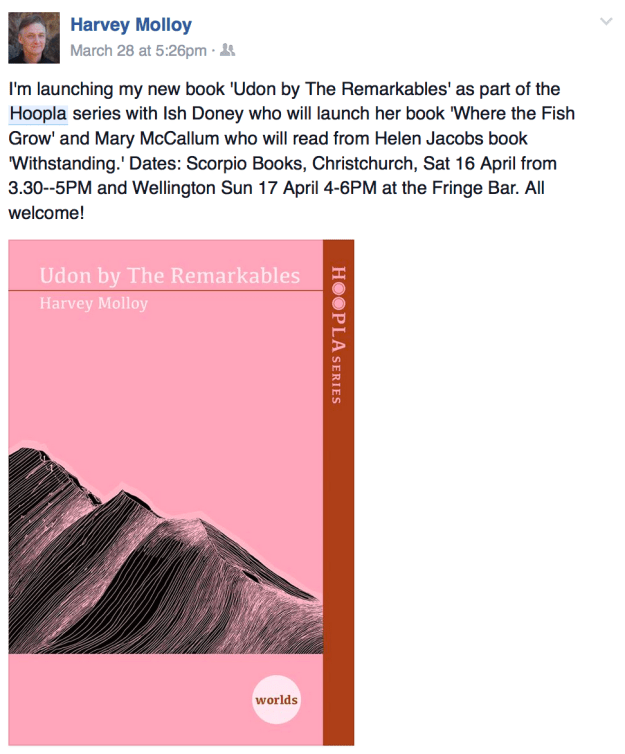

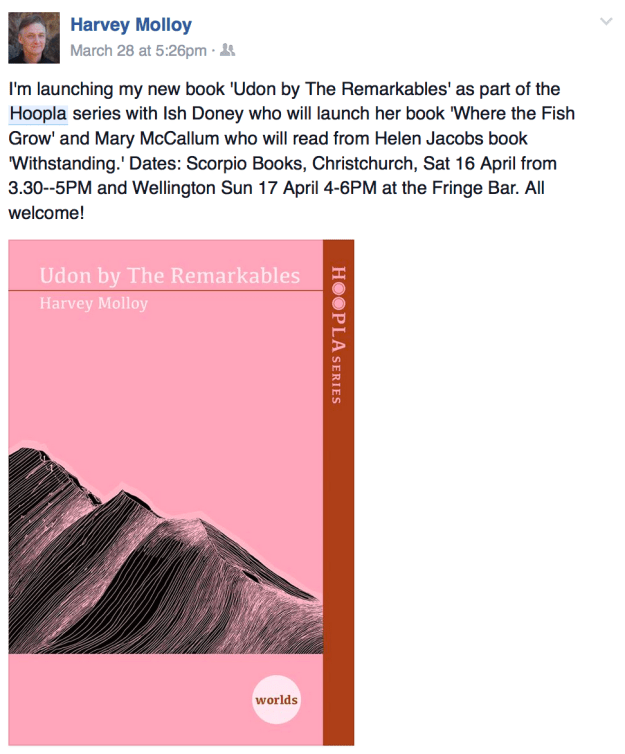

Hoopla 2016 Poetry series to launch in Christchurch

Leave a reply

Mary McCallum of Mākaro Press interviews debut poet Jamie Trower about his collection Anatomy, which they published under their Submarine imprint in 2015.

(for my review of the book see here)

Mary McCallum: As a new poetry publisher we get a lot of emails from people wanting to submit their collections of poetry. Some of those emails are like explosive devices — as soon as you open them you know you’re in danger. All the tiny words on the screen shimmer with the excitement of being written by someone for whom words are not simply tools or exciting ways to evoke the world of experience or imagination, but tiny rockets that have changed or saved a life.

This was the case when I opened an email from Aucklander Jamie Trower – a young man in his early twenties who had only just discovered poetry, but who had nonetheless crafted a whole collection that he wanted me to read. A collection of poems that charted his recovery from a terrible childhood brain injury that could have killed him.

What a ride. It felt to me reading Anatomy for the first time – and I continue to feel this – that Jamie had given himself permission to write how he wanted to write, and discover what he wanted to discover using words in a way that he’d never thought possible. With obvious delight he raged on the page, and laughed at and interrogated it. Words came and he connected them and lit the fuse. Which is not to say Jamie wasn’t open to editing. He was. He loved the whole process … more of a chance to play with words, more connections to fire. We published it, dear reader, and this week I talked to Jamie about the book so close to his heart – how he wrote it and why, and where to now.

M: What made you start to write poetry?

J: In the months of rehab after I sustained a severe brain injury as a nine-year-old, I learned to use a typewriter. I wrote sporadic, jumbled notes of how I was feeling and the changes I noticed in my wheelchair-bound body. I really started writing poetry after taking a creative writing course at the University of Auckland two years ago. It was then that I went back to the notes that I wrote in rehab and found myself expanding and stretching the words into poetry.

M: What do you like about it?

J: The beauty and ease of poetry. How a single moment can be expanded on, heightened, strengthened, transformed, stretched, redefined and moulded in a couple of lines. How a writer can adapt a thought, a feeling or an event so easily through compressed, rhythmic language.

M: Who are your poetry heroes? Are there any poets you try and emulate?

J: I am in awe of Sam Hunt, Paul Muldoon, Ben Okri – the list goes on! I think their writings are compelling and eloquently formed. I draw on their poetry quite a bit – how they use simple thoughts and words to create a big impact.

M: Your poetry collection feels like one long narrative poem about what you went through when you had a brain injury as a child – rather than lots of separate poems – do you see it that way?

J: Anatomy is definitely narrative in its structure: a start, middle and end. I tried to separate the poetic canvas by titling the poems – making it feel like more of a collection rather than a narrative – and pairing it with a traditional form of storytelling. I decided in the editing process to parallel poetry with prose to guide the reader, and to allow the emotion I felt to show through more.

M: In Anatomy you indicate the typewriter was an important tool in your rehab – is poetry also important as a form of therapy in getting over what happened to you?

J: Poetry will always be my rehab, my therapy, my hospital, my home. This use of self-expression and self-examination helped me (and still does) realise that I needed to take control of my own body, my own disability. I hope to continue to use the lessons that poetry has taught me for many years to come.

M: What are you writing now?

J: I’m writing my next poetry collection, and I’m brainstorming a novel on the side. I’m excited to see what comes of it!

M: Who are you reading?

J: Right now I’m reading Michele Leggott’s Heartland (for the tenth time, it feels). She very kindly came to the launch of Anatomy, which was very, very cool.

Mākaro Press page

Jamie Trower Anatomy Mākaro Press 2015

At the age of nine, Jamie Trower suffered a traumatic head injury when skiing on the slopes of Ruapehu. After months in a coma, he spent two years at the Wilson Centre in Auckland. Jamie is currently based in Auckland where he is studying English and Drama at the University of Auckland. Anatomy is his debut poetry collection.

Anatomy rebuilds anatomy. The word ‘disability’ (disabled, disable, disablement) is like a shadow protagonist that Jamie pitches against and from. It felt like a physical presence, an entity to interrogate as Jamie navigates his recovery paths. To read our way into and out of ‘disability’ is to thwart ‘unable’ and latch upon ‘enable.’ It is to follow Jamie from the accident and rocks to his cloud nine.

I felt a little nervous opening the book, as in the middle of my PhD, I smashed into a glass door and suffered the effects of post-concussion syndrome for about a year. Everything was thrown in the air as I struggled to make sense of the world let alone my academic research. My ability to speak and write and c0mprehend (and hang out the washing, cook dinner) was utterly compromised. Once I started reading Anatomy, the twitchiness at revisiting the memory of my vulnerable head faded.

This book is poetry as record, it is poetry as reboot and poetry as rehabilitation. Writing becomes a way of refurbishing self and moving through. You are carried along by the fluency of the line, so lyrically, yet there is the white space of hiccup. Some words are stretched out as though we say them slowly ( d i s a b i l i t y, t h i n g). Some words drop down the page like a teetering step ladder to cloud nine or back down to earth. The poetic choices heighten the struggle to recover, and to face what recovery means.

This is a poetry collection that moves and elevates you, that records a devastating experience at the most personal of levels, and that plays with what words can do (from the first clacks and clatters on the old typewriter he was given by his teacher). Wonderful!

from ‘( m a y b e , t o m o r r o w )’

m i g h t

hybridize

from teenage boy

in

n a p p y & pacifier,

to a mighty sea bird –

to a juvenile juggernaut

– dancing

in the wild …

to whistle

in rainbows

of thistles,

(ocean spray) …

Mākaro Press page

‘You see the day as a kind of wind’

I am currently loving Bryan Walpert‘s Native Bird (Mākaro Press, 2015). Reading this book is like entering a restorative glade. Or a slow paced European movie where the camera takes one long slow delicious pan that sweeps and lingers and stalls and accumulates the faintest detail, the hint of movements, the tremor of action. And out of the long gorgeous sweep of reading, you get place, character, story. Or think of this rhythm as a sticky ribbon to which detail adheres. The detail catches you. Phrases, whole lines, stanzas. The sound of each line strikes your ear – beautifully, honey-like. The world slows because this is one of those books where the poems reach out and hold you in the grip of attention. I adore it.

from ‘Wayward ode’

I’ve rewritten this three times. How many

transformations must it take before you hear me

call through this drafty window of ink?

A Potato Sonnet: Jersey Bennes for Christmas

They gleam in the black

crumbled earth;

steady, as if candles

glow through layers of silk,

underpin the season’s quick

shifts of tinselled light

and the brisk heel-tap, chatter

of crowds in the street.

This is old, wondrous

as moon-rise,

mundane

as the maternal voice

that calls, come in

to the table.

© Carolyn McCurdie Bones in the Octagon Mākaro Press 2015

Author Bio: Carolyn McCurdie is a Dunedin writer. She won the Lilian Ida Smith Award in 1998 for short stories and a collection of stories — Albatross was published in 2014 by e-book publisher Rosa Mira Books. A children’s novel, The Unquiet, was published in 2006 by Longacre Press. She was the winner of the 2013 NZ Poetry Society International Poetry Competition and her first poetry collection, Bones in the Octagon, was published in 2015 by Mākaro Press as part of their Hoopla series. Carolyn is active in Dunedin’s live poetry scene, where she is a member of the Octagon Poets Collective.

Paula’s note: The potato is comfort food, but this particular potato hooks you to the extended family table where the sun is blazing down and family stories circulate. Christmas. Ah. Reading the poem, each word gleams in the light bright space of the page along with the deep pit of personal memory. Each word is so perfectly placed for ear and eye. This is the first poem I read in Carolyn’s debut collection (the title lured me in — especially the idea of a sonnet meeting up with potatoes). There is a quietness, an attentiveness, delicious overlaps of meaning and propulsion. I can’t wait to settle back into the book and discover more.

Mākaro Press author page

Other books in 2015 Hoopla series:

Mr Clean & the Junkie by Jennifer Compton (I reviewed this here)

Native Bird by Bryan Walpert

Jennifer Compton, Mr Clean & The Junkie Mākaro Press, 2015

Jennifer Compton’s new poetry collection, Mr Clean & The Junkie, is a fabulous read – the kind of book you devour in one gulp. It is a long narrative poem in four parts with a coda. Each section is written in couplets – shortish lines that deliver the perfect rhythm for the occasion. This is a 1970s love story set in Sydney (and briefly NZ), yet it is a love story with a difference. It reminded me a bit of Pirandello’s play Six Characters in Search of an Author, in that the stitching is on show — how you tell/show the story, along with the choices you make, is as much a part of the narrative as plot, characters and so. The difference here, though, it is like a poem in search of a character in search of a film director in search of character in search of a poem. Self-reflexive behaviour on the part of authors has been done to death in recent decades, so it has the potential to appear lack lustre. Not in this case. I loved the way the poetry is a series of smudges. A bit like the way life imitates cinema as much as cinema imitates life.

I spent ages on the first page. It got thoughts rolling. I loved the voice. I loved the intrusion of the director (we figure that out as we read) and I loved the way I kept putting the poem in the role of the camera (long shots to gain wider perspective or distance, tracking shots, surprising angles, refreshing views) or the editing suites with jump cuts and smooth transitions. Or sitting back and admiring the composition within the frame. Or tropes. The slow reveal.

The two main characters (My Clean and The Junkie) are definitely in search of flesh and blood, yet you can also see this as genre writing – a narrative poem that is part thriller, part whodunit, part crime writing. Then again it is part feminist critique and part postmodern explosion.

Here is a sample from the first page:

Our hero is discovered sleeping.

We find him as the camera finds him.

Our hero is dreaming of the white mouse

cleaning his whiskers in extreme close-up.

As he dreams we snoop about his habitat.

Everything is there for a reason and we will

see it from another angle before we reach The End.

I imagine ambient sound during the credit sequence.

The mouse begins to run the wheel because

the wheel is there under his paws.

The slow zoom out reveals the wheel is in a cage,

of course.

And fade to the floor-to-ceiling, slatted blinds,

chocked ajar,

looming over our man asleep on his futon.

What do they look like? Bars.

The writing is tight. The plot pulls you along at break-neck pace and then stops you in your tracks as the director’s voice pulls you out of plot and character with wry stumbling blocks. Little flurries of sidetracks. Or how to proceed? The central idea’s beguiling (poem version of a film version of a love story), the dry humour infectious (after a curtain is pulled back to reveal a spectacular view of Sydney’s Harbour Bridge and Opera House: ‘If you’ve got it/ flaunt it.’). But there is poetry at work here. It is there in the cadence of each line, the end word and the rhythm. It is there in the use of tropes that arch across the length of the book in little delicious echoes. The caged mouse on the wheel stands in for the symbolic cage of the hero (his father’s expectations and life choices). Most of all, however, the poetry sparks and flicks in the white space; the bits that are left on the editor’s floor or the angles that the director chooses not to show. Things are hinted at. Significant events that give flesh to character are caught within a line or two. That white space, that economy, is what gives this long poem its magnetic pull.

The collection is released as part of Mākaro Press’s 2015 Hoopla series. The beautifully designed books share design features and size, and include a new poet, mid-career poet and late-career poet. The other poets this year are: Carolyn McCurdie (Bones in the Octagon) and Bryan Walpert (Native bird). Jennifer is an award-winning poet and playwright who has lived in Australia since the 1970s. She has won both The Kathleen Grattan Award for Poetry (This City, Otago University Press, 2011) and The Katherine Mansfield Award.

Reading Mr Clean and The Junkie is entertaining, diverting, challenging, laughter inducing. How wonderful that a poetry collection can do all of this. I loved it!

Bones in the Octagon by Carolyn McCurdie, Mākaro Press, 2015 (part of The Hoopla Series 2015, see below for other two titles)

Launch notes – Emma Neale

I’ve spoken in public before about first coming across Carolyn’s fantasy novel for children, The Unquiet, in manuscript form at Longacre Press. I felt then a sense of breathless disbelief that something so sharp and lucidly poetic, was just sitting there, looking like any other mild-mannered typescript in the unsolicited submissions pile. It should have been thrust into the air gleaming like the sword from the stone in myth. Hyperbole, you might think, but the novel went on to be named in the Storylines Trust list of ‘Notable Books of 2007’, and I still stand by my description of it as a novel that seems Frameian in its use of gentle abstraction, natural imagery, and its empathy for the child’s eye view. Carolyn’s use of imagery there lay potent clues for what she also does in her poetry.

Mākaro Press have done a gorgeous job of producing this first collection of her poems —her first poems, but her third book. (There is also an ebook of short stories called Albatross, published by Rosa Mira books.) I love the feel of the whole Hoopla series as tactile objects — the fact you can slip them into your bag or capacious coat pocket like a Swiss army knife — bristling with tools for the mind — and the fact that it comes with two free bookmarks — (i.e. the side flaps) — or wings, symbolically ready for launch.

When I first started reading Bones in the Octagon, very early on I wanted to pluck out the phrase ‘shy iridescence’ to characterise Carolyn’s poems. But increasingly that came to seem lazy, insipid, because while the poems might have a kind of chromatic shimmer of mood and topic, the dart and race of illumination, the voice is anything but reticent. It is often, I think, steely. There is an inner resilience here; a voice that holds its strong, pure note even when face to face with everything from physical drought to domestic violence, psychological abuse, suppression, bereavement, political corruption, dislocation, and deep dread. Resurgent, the voice always lifts. And throughout, even when confronting darkness, it somehow still hums with wonder.

Carolyn’s poems can reach back to the first footprints and hungers of human civilisation, feeling out for connection to our earliest selves; they can hone in on the present, with condemnations of political expediency and brutality; they can have the dreamlike urgency of premonition; the shiver of fable lodged deep as inherited instincts, bred in the bone. Some, like ‘Making up the spare beds for the Brothers Grimm’, contain a sense of threat and corrupted relationships that go right down to the roots of a primal terror — there are traces here of abuse, damage, disillusion. Yet the touch is so light and the poetic control impeccable.

Often the voice in the book seems to speak in the firm but whispered imperatives of a mentor, parent, even a spirit guide. (Here is just a small sample: don’t cross, cross now, go through, walk with me, pack no bags, don’t look back, stand by her, watch out, shush, look there, please leave, come in, measure, wait…and again wait…. and wait.) There’s the sense of a markswoman with her arrow pulled back, tense, taut, not even quivering — then thwish — the poem is released.

Carolyn’s range is wide: she draws on world myth, local human and zoological history, the urban present, the transcendent imagination of childhood, a feeling of secular prayer and benediction. ‘Verbal Thai Chi’ is another way to describe the atmosphere of her work. She catches the heady lift of music ‘the intoxication of song’ as she calls it; she has a long view, of gradations of deep time — yet she is also vividly alert to the smallest shift in interaction between people right now, in the living minute. (I’ll just say here, watch out for the eyebrows.)

Her language, in its crisp repetitions, might imitate a bird in flight; her use of line break and white space can capture the way a ‘silence is vibrant’ […] ‘As when you enter a room/and conversation stops’ ; the careful accretion of information builds like a web of narrative, every strand or line holding the whole design in place. There can be gentle, plangent word play which shows the way the subconscious can both pun and express loss, can show the past so indelibly written on the mind’s memory maps.

Throughout the book, there is an awareness of the atavistic, of someone listening in closely to the primitive within us, but with something like a physician’s training and carefulness. It made me think of the title of a Les Murray collection, Translations from the Natural World, but where Murray’s work sprawls and layers, Carolyn seems to have a porous sensitivity that she still manages to whittle down to a fine wire of narrative; to forge the line till it strikes a clear, ringing note.

I could say so much more about Carolyn’s work, but I want to close by saying that as in her poem ‘Hut’, her work has corners that shelter tenderness, and offer us refuge. To use her own lines to sum up the strongest qualities in her work, and to make a ‘virtual’ toast to Carolyn here: “Fire, music, you. Another sip.”

Chris Tse

I emerged from a film festival-induced haze to find that my to-read pile has grown exponentially. (Fittingly, one of the books that I’ve recently finished and enjoyed is Helen Rickerby’s Cinema for its wistful and charming tales of reality colliding with the world of movies.) Near the top of my daunting pile are Maria McMillan’s Tree Space and Hinemoana Baker’s waha | mouth (both VUP, 2014), and Sam Sampson’s Halcyon Ghosts (AUP, 2014). I’ve also been itching to get stuck into When My Brother Was an Aztec by Natalie Diaz (Copper Canyon Press, 2012). I stumbled across her poem ‘My Brother at 3am’ and then went searching for whatever else I could find by her.

I’ve been dipping in and out of books by two American poets (there’s a spooky synchronicity with their titles): Scarecrone by Melissa Broder (Publishing Genius Press, 2014) and Scary, No Scary by Zachary Schomburg (Black Ocean, 2011). Both write deliciously dark poems, which read like fables that speak of how terrifying and confusing the modern world can be. At times these poems have an irreverent edge to them, and both poets use such precise language and ominous images to conjure up worlds of unease.

Chris Tse‘s first poetry collection, How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes (AUP), will be available in stores and online from 22 September.

Hinemoana Baker

Bird murder When I closed this book after reading it for the first time, my exact words were ‘Now that’s how it’s done.’ Bird murder is a dark chronicle of close-packed language and noir thrills. Being a bird-lover from way back, I delighted in the book’s central murder, and I secretly hoped it was the Stellar’s Jay itself that did it. Overall, though, it’s simply the exceptional quality and music of the sentences that blows me away. An example from ‘Setting’:

Mrs Cockatrice, pink hair a-boule

sets the table for her guests.

Her ornamental milking stool

will do for a child.

And one more, from ‘Solar midnight’:

I came from a lake with an island on it

and on the island there was a lake.

The water was so silver. I had feathers then.’

– Bird murder by Stefanie Lash, Mākaro Press, Hoopla Series. Eastbourne, 2014.

The Red Bird I was alerted to Joyelle by Shannon Welch, whose Iowa Writing Workshop I attended at the IIML in 2003. It would be hard to overstate the effect it had on me reading these lines from ‘Still Life w/ Influences’:

Up on the hill,

a white tent had just got unsteadily to its feet

like a foal or a just-foaled cathedral.

I’ve been known to say loudly, on several occasions since, if I’d written that I could die happy. A glib hat-tip but the feeling is entirely genuine. This particular book travels from whales to guitarists to car accidents and beagles and doubles back. In the introduction, Allen Grossman says Joyelle ‘is a poetic realist. Her poems are neither reductive nor fantastic. But they are profoundly mysterious in the way any truthful account of the world must be.’

– The Red Bird by Joyelle McSweeney, Fence Books / Saturnalia Books. New York NY, 2002.

Hinemoana Baker‘s latest collection of poetry, waha | mouth, has just been released by Victoria University Press. I will review it on Poetry Shelf.

Karen Craig

Two poets I’ve been spending a lot of time with recently are Thom Gunn and Mark Doty, prompted by my job at Auckland Libraries, where we’ve been working on adding some lists of recommended reads in GLBTQI fiction and literature to our website. Thom Gunn is an old acquaintance who never ceases to awe me with the hard (yet supple — how they suited his poems, those black leather biker jackets) intelligence of his vision and the cool leanness of his language. The book I’m reading now is the Selected Poems edited by August Kleinzahler (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009), which includes my favourite poem ‘Considering the Snail’, where the snail “moves in a wood of desire,/ pale antlers barely stirring/ as he hunts.” That’s already good. “What is a snail’s fury?” That’s genius, for me.

Mark Doty is a new find for me. A friend recommended his memoir Dog Years for a “Sadness” display we did at Central Library, saying it was the saddest book she’d ever read. If I tell you it’s over 200 pages and I read it all in one day and night, that will give you an idea of how this man gets inside your heart. He’s one of those people that when I was in high-school we used to call “beautiful”, and, when we used the term in our English essays, be told — rightly — that it was too imprecise. So to be more precise on Mark Doty’s beauty: a largeness of spirit, a sense of wonder and mystery, emotivity and desire, the musicality of the ordinary. I’m reading Paragon Park (David R. Godine, 2012), a collection of his early poems, while waiting for the more complete collection Fire to Fire (New York : HarperCollins, c2008). To match Thom Gunn’s snail, an amazing “Turtle, Swan”, where he addresses his lover, at the start of the AIDS epidemic, “you with your white and muscular wings / that rise and ripple beneath or above me, / your magnificent neck, eyes the deep mottled autumnal colors / of polished tortoise — I do not want you ever to die.”

On an other note, I’ve got Michele Leggott and Martin Edmond’s Beyond the Ohlala Mountains: Alan Brunton, poems 1968-2002 (Titus Books, 2013) from the library. I’ve just started dipping in, but I could see immediately that this is the kind of book which makes you really understand what is meant by “labour of love”. Beautifully composed, a careful, pondered – never ponderous – and, subtly, poetic introduction, which will have something for everyone. And the poems! A universe, no, a multiverse, of raptures and pandemoniums.

About me:

I work at Auckland’s Central City Library promoting fiction and literature both on the shelves and off the shelves, through book launches, author talks, lectures and — with great joy, always – poetry celebrations, including National Poetry Day evenings in conjunction with nzepc, Stars of Pasifika Poetry every March, and The Day of the Dead Beat Poets, every November 2. For the next 12 months I’m serving in a just-created role focussing on initiatives across the libraries to raise awareness of our collections. I write the Books in the City (http://albooksinthecity.blogspot.co.nz/) blog.

Helen Rickerby, Cinema, Mākaro Press, 2014 (part of the Hoopla Series)

‘With a whirr and a click/ we’ve conquered distance and memory’

There is an anecdote that the Italian film directors, the Taviani brothers, saw a movie when they were adolescents that rebounded a version of their world back to them (the constellation and collision of worlds that we know as Italy) and they dramatically said, ‘Cinema or death!’ Such boldness in the light of this shared epiphany.

Helen Rickerby’s terrific new poetry collection takes you into the world of cinema. Fittingly, the first poem is entitled ‘When the Lights Go Down.’ I immediately stalled on the title and pondered on the shared experience of reading poetry and watching a film. Even in the public space of a cinema, there is something intimate and private about your immersion in the cinematic world. It is comparable to entering a splendid poem and letting the world fade to pitch black along with the barking dog and the wet laundry— it’s just you and the poem.

In this book, ‘cinema’ is a thematic glue that gives the collection cohesion, but it is also the ingredient that animates at the level of detail. If you love film, and you have a history of film viewing, then this collection offers abundant rewards.

An early poem, ‘Revolutions,’ leads you into various meanings of the word from the click and whirr of the camera and the projector to the daring work of pioneer filmmakers. And so it is with the poems– the poetic effects are various, whether humorous, confessional, inventive, challenging, insightful, quirky.

There are a series of wry poems that re-imagine the life of a friend or Helen herself as directed by a particular filmmaker (Ken Russell, Sergio Leone, Quentin Tarantino, Stanley Kubrick, Jane Campion, and so on). ‘Chris’s life, as directed by Ken Russell’ is particularly witty. When Chris awakes to find ‘an anteater on my chest/ tearing at my throat’ it is , as Ken says, ‘the anteater of self-doubt.’

There is the way cinematic life has the ability to seep into and become saturated in your own (or vice versa) as the title of one poem suggests (‘Impressionable and impressed’). Thus the last verse of this poem hooks you:

What these poems do, too, is capture the magical, mysterious pull of cinema where there is a physical interplay between light and dark that then shifts beyond the material to an interplay between intellectual and emotional levels. Light and dark’s electric connections become the connections between life and death, desire and indifference, ghosts and humanity, real life and fantasies. In ‘Camera’ there are numerous such ripples —and the opening lines signpost the burgeoning magic: ‘There are lots of different stairs to be climbed/ each with a different kind of railing.’

The collection has an intermission! As though we can make our way out of the dark to collect popcorn or ice cream. I have never thought of this before, but I feel like I install a miniature intermission after each poem I read (if it is any good!) in order to absorb the poetic complexities or savour the poetic simplicity.

I love the way Helen’s collection pulls you into a poetic mis-en-abyme—into layers and levels of translucence, symbols, self exposure, tangible details, ephemeral details and above all a contagious love of film. Not that it’s a terrifying vortex! It is just deliciously complex.

Several longer poems stood out for me. I love the glorious ‘Two or three things I know about them’ which carries you along the white-hot tension between Jean-Luc Goddard and François Truffaut, and their different approaches to making a film. I also particularly loved ‘Symbols that make up the breaking up girl,’ a lush poem in parts where each part exudes a joy of language. Then there is the wonderful density and intensity of detail, with shifting tones and fitting repetition, in ‘A bell, a summer, a forest.’ I also delighted in ‘Nine movies,’ a sequence of poems that filter love and personal life through somebody else’s movie plot, incidents and discoveries.

Each poem in this collection is like an aperture into the magical world of cinema which in turn is an aperture into the magically fizzing world we inhabit—in all its shades of light and dark. And this then becomes poetry. As a big cinema fan, I loved it.

Helen is a poet, publisher and public servant with three previous poetry collections to her name. She runs the boutique Seraph Press and is the co-managing director of JAAM. Along with Anna Jackson and Angelina Sbroma, Helen is organising Truth or Beauty: Poetry and Biography, an upcoming conference at Victoria University. Details here.

Mākaro Press website Hoopla page

Helen Rickerby’s Seraph Press

Helen’s blog Winged Ink

An interview with Helen