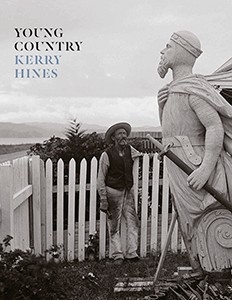

Kerry Hine, Young Country, Auckland University Press, 2014

Kerry Hine’s debut poetry collection is an offspring of her doctoral thesis, ‘After the Fact: Poems, Photographs and Regenerating Histories’ (Victoria University, 2012). Her thesis considers the photographs of William Williams amongst other things and these alluring photographs act as prompts for her poems. William was a well-regarded, nineteenth-century photographer with a passion for the outdoors, and for railways in particular. He walked and camped and canoed. He photographed both rural and urban settings. Kerry’s poetry comes out of scholarly endeavour; the research is acknowledged at the back of the book in the bibliography and the extensive notes on both image and text. The thesis title, ‘After the Fact,’ resonates with intellectual and poetic movement. The writer takes a step back into history (to view the images, read material), yet she steps off from the fact of the matter (the staged scene, the fallible anecdote) to her own territory. The photographer has framed a set of circumstances selectively with his own eye/slant, and the poet does likewise. You could say the poem, ‘after the fact,’ is a second framing where invention rubs shoulders with historical records. Reading the poems in this context raises questions. What links are made to history/histories? Can we spot the personal predilections of the poet? Do we need facts? Can poetry reframe history in a way that draws us deeper into the past. Can we track both minor and major narratives in image and poem?

Before I started reading the book, I decided I had three options. First option is to read the photographs and follow the melancholic edge of the dead scenes, the fascination of the frozen moment, without the poems. I did this a little and loved the movement that each image ignited, belying both death and the stoppage of time. Always that trace of melancholy though. Second option is to read just the poems and try and ignore the mesmerising flicker of image in the corner of my eye. That was tough as the photographs tugged me away. Yet to stop and enter the heart of the poems was rewarding. I got carried into the territory of elsewhere. Third option is to read page by page, poem and photograph, and enjoy the flavoursome link and sidesteps. This is what I did in the end.

Young Country is a beautifully produced book with its sheen of paper, white space, terrific reproductions, inviting openness of font and internal design. Auckland University Press is exemplary in its book design and this book is no exception.

Kerry’s poems do take you back in time where men are catching eels, felling trees, smoking pipes, drinking whiskey, tenting, pondering the meaning of life, being alone. What of the women? I especially loved the multifaceted portraits of the women. There are the wives, the mothers — but then, the surprise of the butcher’s wife who darns a man’s hand. Or the rising questions of the new wife (‘Not doubts. Little questions.’). Or the woman whose ‘bed has grown around her,/ trying to accommodate// her illness.’ An illness defined as feminine hysteria with the cure a prescription to breed, constantly breed. Or the little resistance of the widow:

The Widow

An apple is an apple

is a simple fruit.

What women are supposed to need

I can do without.

What men can do

I can do without.

The photograph opposite this poem is an empty, gravel road heading into the bush in Masterton. A scene awaiting the pitch of the axe, the hearty yarn, the doing and the not-doing, and the needed and the not-needed.

Photo credit: Forty Mile Bush, Masterton William Williams c1885 (1/1-025950-G)

There is both elegance and economy at work in the poetry; a judicious use of detail that is like the visual snag of a photograph. Context becomes enlivened. In ‘Wellington,’ the scene is set perfectly in the opening lines: ‘Young men in bowler hats/ spring up like weeds.’ Or this in ‘After the Flood’: ‘Over our heads, debris in the trees.’ In the same poem, a scholarly observation adds historical detail: ‘Geometry gave way to geography. The settlement found its own course.’ In ‘Sarah,’ the detail of living: He writes of ‘his eel and/ spinach pie, cooking/ with gorse,’ while she answers ‘with trees/ blown down, a bee-stung/ tongue.’ The weather, too, refreshes the page with inventive detail (the best weather lines I have seen in ages!): ‘The absence of moonlight/ a kind of weather.’ ‘The river, rinsed of sunlight, is running/ clean along the bank.’ ‘[T]he scraped canvas of the sky/ the sky dropped and put back before/ anyone could notice.’ ‘Rain stings the window,/ rattles the wall.’ ‘The rain snaps at house./ The house recoils as if bitten.’

Detail animates the terrific extended sequence, ‘Settlement.’ The detail accumulates satin lining on upside down spout, grown boys on the smell of grenadine. This is the portrait of a woman, a wife and mother that moves and astonishes. Always the achingly real detail that ties interior to exterior, man to woman, place to person. Some lines are quick to the bone as you read:

No stepping stones, but

rocks in a river.

A storm of summer insects,

lightning birds.

She says the things that

someone ought to say.

The water’s arguments run

for and against.

The cold is shocking

but she keeps her feet.

William’s photograph a few pages earlier, with the empty chairs, the tea cups in the dresser and the guns on the wall, is also a portrait of the woman (a woman). You fall into this photograph and you fall into a thousand household stories. The chores, the time passing, the world outside, order, expectation, internal and external means of survival.

Photo credit: House Interior William Willams 1888-? (1/2-140288-G)

As much as I loved the way the poems transport me back within a historical frame, to those men and women bending into the strangeness and toughness of new lives, two things stood out for me in this collection: a sense of humour and a fearless and inventive use of tropes. Many contemporary poets hold tropes at arm’s length as they seek out a plainness of line (although other complexities and delights take hold of the ear). Kerry’s tropes so often fan the visual impact of a poem. Crackling with visual impact. Deliciously fresh. Here are a few of my favourites: ‘The bush grows back/ like a balding man’s hair.’ ‘He sang like an organ making up the fire.’ ‘The breast-stroking sea/ turns at the wall.’ ‘Night surrounds her like mint cake./ She feels its grit in her teeth.’ ‘[H]is consciousness of her/ was like a trunk of empty/ clothes; he was embarrassed/ to be caught holding them/ against himself.’ Glorious.

The humour is another gold vein. Sometimes it is a mere word. In ‘Tom at Board,’ a new word is coined that wickedly catches the sameness of dinner: ‘served up with/ muttononous regularity.’ Or the irony of the lost pipe: ‘For the others’ sake/ he tried to keep it safe// between his teeth.’ Or the way humour takes root in the familiar in this case of insomnia: ‘the ill-mannered sheep/ have forgotten how to be sociable/ except with rocks and bushes.’ Humour is one way Kerry sidesteps from the photograph. It is way of ensuring her poems are visually and emotionally active.

Yet this collection is not all humour and eye-catching tropes — in this astutely crafted collection there is balance. You fall upon a line here and a line there that shows you the poet viewing the world and our myriad ways of inhabiting it. Now the poet becomes part philosopher: ‘Home is a road/ in a glen.’ ‘We have no seasons,/ only tides.’ The oxymoron: ‘A land of opportunity, a land of/ narrow possibilities.’ ‘The photographer’s wife’s sister/ is a kind of sum.’

I loved too the epigramatic poems. Without titles they act as delightful poetry interludes in the way Bill Manhire’s billowy couplets do. Here a few favourites:

he sings the old songs,

enjoys a couple of good notes

Or:

afterwards he waited as

she sewed his buttons back on

Or:

Three in the morning. Tui,

morepork. No, but. No, but.

Kerry’s debut collection is haunting and complicated. Down to earth and resonant. One line is like an entry point to the whole collection: ‘She had been thinking something other,/ out of the photograph.’ Reading my way out of the poem, is a prismatic experience. Into history yes, but the poems are also a way back into the present. How we live now overlays how we lived then. Still labour. Still love. Still loss. Still hunger. Still narratives. The poems are held against the light. Luminous. With shifting points of view. This wife and that husband. This river bank and that shingled street. This suffering and that loneliness. This bridge and that glass in hand. I am hard pressed to recall a collection quite like it — a whiff of John Newton or David Howard or Jeffrey Paparoa Holman perhaps. Angela Andrews. Chris Price. Marty Smith. This is worth reading.

Auckland University Press page

Kerry Hine’s page

National Radio interview with photographs