Category Archives: Poetry

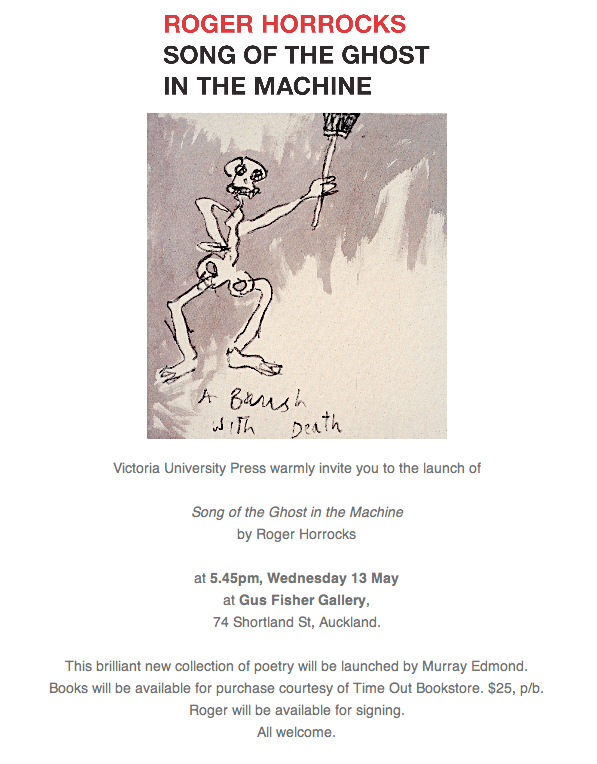

Launch of Roger Horrock’s Song of the Ghost in Auckland

Charles Brasch: Selected Poems edited by Alan Roddick He is splitting his poems in ways that promote new revelations

Charles Brasch: Selected Poems edited by Alan Roddick, Otago University Press, 2015

Poet and scholar, Alan Roddick previously edited Charles Brash’s posthumous collection, Home Ground (1974) and his Collected Poems (1984). Charles published a number of collections in his lifetime, mentored younger poets and was the founder and initial editor of Landfall. With his books all out-of-print, this is a timely arrival. One of New Zealand’s most influential literary journals, Landfall has represented poetic trends over decades, and continues to endure with renewed vitality (currently edited by David Eggleton), but it is interesting to step aside from this legacy and explore Brasch’s own poetry. He was a contemporary of RK Mason and ARD Fairburn and was selected by Allen Curnow for A Book of New Zealand Verse in 1951. For many poets, this was a sign of having made it. For Brasch, it knocked back some of the self doubt and sent him traversing new poetic paths. It was indeed a turning point.

One fascination of a selected poems is the way they cover the arc of a poet’s life and, in particular, writing life; the way poems reflect interior changes, and the way a changing world rubs against the process of writing. Charles’s first collection, The Land and the People, was published in 1939 with looming threats of war and world instability. He wrote with an initial attachment to the Romantics but by the 1970s his poetry was freer. The language is less tied to loftiness, to the abstract, to tight rhythms. He writes in plainer language, everyday language, yet you still see resolute connections with the subject matter of his first book: the land and the people. In many ways, the poetic arc of Alan’s selection lays its roots in Brash’s attachment to home, and the poem becomes a frame or form for a navigation of this. A homage at times. A questioning of sorts. Charles held the war at arm’s length, he held the rumpus of the 1960s at arm’s length (you don’t see him in Big Smoke, the anthology that highlights the radical poetry of the 1960s and 1970s). In his last decade or so, he is not rupturing form and content across the page in ways that SHOUT and displace. He is splitting his poems in ways that promote new revelations, new confessions whilst always maintaining his private stance. Love is there; love is struggled with and acknowledged but it is never overt, never clear.

from ‘In Your Presence’

I practise to believe,

And work towards love.

How should I see

Until I study with your eye?

He is unafraid to bare the self portrait in ‘Cry Mercy’:

Getting older, I grow more personal,

Like more, dislike more

And more intensely than ever —

People, customs, the state,

The ghastly status quo,

And myself, black-hearted crow

In the canting off-white feathers.

I was interested to discover that he worked on one of his most famous poems, ‘The Islands’ (originally published in his second book in 1948) for twenty years until he felt like he got it right. This is the poem that contains one of the most often quoted lines in New Zealand poetry:

Everywhere in light and calm the murmuring

Shadow of departure; distance looks our way;

And none knows where he will lie down at night.

The poem that has always resonated the most strongly with me is the sequence ‘Home Ground’ (from his last book, bearing that title) and a substantial part of the sequence is reproduced here. The language is sumptuous yet affords a degree of plainness. Individual lines stall and haunt you (‘I tramp my streets into recognition’). It feels open. It feels like writing this poem mattered greatly to the poet because it draws upon what matters. And within that, as with much great poetry, there is space, silence, mystery.

Silence will not let him go

Entirely; allowed a few notes

At the edge of dusk

He will be recalled before long

And folded into rock

Reassumed by the living stream.

Otago University Press have produced a terrific anthology with care taken over internal design and the cover. There is room for the poems to breathe both in terms of font choice and white space on the page. Alan’s introduction is useful but I do think there was room for more discussion of the poetry itself despite the witty inference in Charles’s ‘Pistol Point’ that poems ought to speak for themselves (‘Poems ask their own questions’). Selected Poems is a terrific introduction to Charles’s poetry; particularly to the way his poems shifted over time, on his own terms, and not at the behest of current poetic trends.

Endnote: I have a policy on this blog of using the first name of a poet. This is the first book I have reviewed by one of the key men poets who emerged in the mid-twentieth century in New Zealand, and it feels like I am transgressing a line by not using ‘Brasch.’ It feels like I have invited him into my kitchen to have a cup of tea informally. ‘Authority’ has sailed out the window.

Otago University Press page here

Gregory O’Brien’s terrific discussion with Kim Hill on the book here

NZ Book Council author page here

Tim Upperton’s The Night We Ate the Baby — You need to read the whole collection to get a sense of the tonal subtleties, the echoey anecdotes, the spade that digs open and the spade that buries.

Tim Upperton, The Night We Ate The Baby HauNui Press, 2014

Tim Upperton’s debut poetry collection, A House on Fire, was published by Steele Roberts in 2009. Since then, his poetry has been published in numerous journals and he has won awards for a number of them. The poems for this new collection were written with the assistance of a Doctoral Scholarship from Massey University of New Zealand, so perhaps they form/formed part of his doctoral submission. Tim will be reading as part of the Haunui Press ‘Deep Friend Poetry Reading’ series at Vic Books on 26th March. Details here.

This latest book is unlike any other collection I have seen in New Zealand; chiefly in terms of the measure of discomfort. The forms are various, scooping an edgy wit into prose blocks, villanelle, triplets, couplets and freer patterns. Yet there is connective glue at work here, and that is what makes this collection stand out. I think it comes down to voice (whether or not it is the personal voice of the poet doesn’t really matter) because the voice steering the poems is sharp, forthright, witty, edgy, grumpy. It unsettles. It keeps you on your toes. On the back of the book, Ashleigh Young suggests that ‘[t]hese willfully, calmly disagreeable poems have tenderness and courage at their heart.’ I would agree. Therein lies the pleasure of reading these poems; there is more to the brittle edginess than meets the initial eye.

The first poem, ‘Avoid,’ very clearly announces that this is a poet who loves language, that is unafraid of rhyme and rhythm working arm in arm. The poem is a miniature explosion of sound effects — with sliding assonance, bounding consonants, near rhyme and sumptuous aural connections. It brought to mind the refrain in Don McGlashan’s song, ‘Marvellous Year,’ and Bill Manhire’s glorious ‘1950s’ in the use of rhythm and rhyme, and aural trapeze work that is ear defying. Whereas Don’s song represents a potted portrait of the world in all its warts and glory (in a marvellous year), and Bill’s poem is a nostalgic recuperation of things, Tim sets up the collection’s negative disposition and itemises things to avoid!

New Age mystics. Wave-particle physics.

Federico Garcia Lorca, that all-night talker.

The law. The rot inside the apple core.

All dawdlers. Power walkers. Tattoo

parlours. Death metal concerts.

Poetry readings that go on for hours.

The second poem, ‘Valediction,’ is a list poem steered by straightforward rhyme, and coupled with the incantatory joy of repetition you fall upon the humour. This is a lonesome poem, yet it is unbearably funny.

Goodbye, bagel, table for one.

Coffee, cigarette. Warmth of the sun.

Goodbye, sparrow. Goodbye, speckled hen.

Goodbye, tomorrow. Goodbye, remember when.

The third poem, Spring,’ (it would be so easy to work my way through the book, poem by poem but this trend is about to stop!) is not your usual homage to the season of daffodils and lambs. It is both refreshing and refreshed as the negative bite overturns such empathetic images. You board the slippery slope of the poem and run into the self-deprecating turn of the poet as he surveys the ruins of his touch (‘I ruin the jonquils, the daffodils. I ruin the I love you.’). Beneath this surface of ruination there is a white-hot core of intimacy and loss of intimacy. Unbearably moving. The final stanza holds its most potent kick until the oxymoron in the final line. Spring becomes the vehicle to hint at so much more:

Which is to say, I am terrified.

Meanwhile the grassy goodness, the lengthening day.

It’s not as if you died.

You come closer and closer away.

I was really drawn to ‘The trouble with poetry’ (originally published in Sport). It felt like this poem was a sleuth on the trail of another poem that would in turn become this poem; the Private Eye Poem collected all the necessary pieces (to tell the story in the manner of ‘a poet, not a novelist’). Like many of the poems in the book, it is as much about story as it is about language effects. There are characters and problems and turning points. The poems begins like this:

In the poem

which is like a house

the poet is looking

out a window.

The poem-houses in the book do look out into the world and what they gather in through their wide open and half-open windows are little anecdotes sometimes layered the one upon the other. They house jarring relations, spiky revelations. They are not-love poems as much as they are love poems. They house broken worlds, interior and external. ‘Late Valentine’ is like an ode to what is not:

I don’t sleep with you anymore,

and this makes the rain come

in the open window

The honeyed repetition of a villanelle renders the ‘hook’ in ‘The bare hook’ more damaging. Again there is discomfort, ache, and the oxymoronic kick of a last line (‘The way in is the way out.’) Here’s a sample:

The bare hook where you hung your coat

is a question mark. The answers never.

Don’t ask what this is all about.

You need to read the whole collection to get a sense of the tonal subtleties, the echoey anecdotes, the spade that digs open and the spade that buries — the language that takes to limitless skies, and the forms that contain. This is a risky collection. It’s like a series of negative imprints that if you tilt to the left you get exquisite glimpses of fracture and repair.

from ‘Take care’

You are precious,

so carry yourself carefully

through this day,

don’t drop yourself because

you will smash

and fly apart in every direction,

and then,

and when that happens–

who will gather you,

who will pick you all up

I’d like to know?

Tim’s Blog

HauNui Press page

Poetry Shelf interviews Gregory O’Brien — The poem has to dive down into and surface from some essential state of being

Gregory O’Brien at Tjibaou Cultural Centre, Noumea, March 2015

Photo Credit: Elizabeth Thomson

Gregory O’Brien is the 2015 Stout Memorial Fellow at the Stout Research Centre, Victoria University, where he is currently working on a book about poetry, painting and the environment. His new collection of poems is Whale Years (Auckland University Press). He has published numerous books of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. Since 2011 he has contributed to the ongoing Kermadec art project, works from which are on show at the Tjibaou Cultural Centre, New Caledonia, until July.

The interview

‘Ocean sound, what is it

you listen for?’

Did your childhood shape you as a poet? What did you like to read? Did you write as a child?

As far as I can recall, I drew more than I painted. And I always gravitated towards illustrated books—Tove Jansson’s ‘Moomin’ books stand out, and I remember The Lord of the Rings, as much for its illuminated maps as for the words. I went through a phase of reading comics—Whizzer & Chips rather than Batman. I date my interest in the interplay of words and visual images to those early encounters.

I doodled at every available opportunity and I remember being hauled out of class and punished for drawing, rather well, a crouching deer on the inside cover of my maths book. I usually captioned my drawings—so maybe those captions could be thought of as my first writings. Occasionally I filled in speech- or thought-balloons above various life-forms.

When you started writing poems as a young adult, were there any poets in particular that you were drawn to (poems/poets as surrogate mentors)?

I can trace this pretty exactly, I think. Aged 14: Bob Dylan’s ‘Writings & Drawings’. Aged 15: Dylan Thomas. Aged 16: James K. Baxter and Flann O’Brien (I liked to pretend Flann was an actual relative. I even screen-printed his book-title AT SWIM-TWO-BIRDS on a singlet—an item I still have in my wee box of treasures.) Aged 17: John Cage (Silence, and A Year from Monday). By the age of 18, I was living in Dargaville, and it was as if everybody suddenly jumped on board the NZ Road Services bus or bandwagon—I was reading Kenneth Patchen, William Blake, Edith Sitwell, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, e e cummings; also Allen Curnow, Janet Frame, Sam Hunt… I had known about Eileen Duggan for some years, because she was a relative, on my mother’s side. More than anything else, however, it was discovering Robin Dudding’s journal ISLANDS that turned my world around, that brought the whole business home…. Therein I discovered Ian Wedde, Bill Manhire, Elizabeth Smither, CK Stead…

Did university life transform your poetry writing? Theoretical impulses, research discoveries, peers?

I was six years out of school by the time I finished my BA, so my university life was mixed in, very much, with everything else that was going on: with 15 months in Dargaville, a year or so in Sydney… At university, I certainly wasn’t drawn to theory except in so far as I thought it was a grand imaginative game that might, periodically, yield unpredictable and outlandish results. I enjoyed the pottiness of Ezra Pound’s literary (rather than his political) theorising… An ABC of Reading is a great book. Probably the Zen-inclined John Cage and the Trappist Thomas Merton were the two non-fiction writers I held closest to me.

Reading your poetry makes me want to write. I love the way your poems delve deep into the world, surprisingly, thoughtfully yet never let go of the music of the line. Words overlap and loop and echo. There is an infectious joy of language at work. What are key things for you when you write a poem?

I listen to a lot of music. I want the poems to have something of the music that I love. I spend a lot of my time looking at art. And I want my poems to have something of the art that I love. There are aspects of composition, tone, rhythm and character which span all these different creative modes. Those are the key factors for me when I write… At a certain point, an appropriate form makes itself known…. The poem has to dive down into and surface from some essential state of being… There is certainly a joy in doing the things that you love; so there’s joy in the making and, preceding that, in the state of being that leads to the making….

Do you see yourself as a philosophical poet? Almost Zen-like at times?

My concept of philosophy is broad and shambolic enough to accommodate what I do as a writer. I’ve never read extensively in the field of Zen (apart from the books of John Cage and the writing of my friend Richard von Sturmer). I’ve read a little, and somewhat randomly, in the field of non-conformist Catholic thought: Simone Weill, Meister Eckhart, Merton, Baxter… These peregrinations may have affected me more than I realise or am prepared to say.

Do you think your writing has changed over time?

I guess writing has to evolve – otherwise it will become predictable and a total drag. I’m as entranced as I ever was with the process, the business, the labour of it. At the same time, I remain devoted to the finished form of it: The printed book, with its covers and half-title and title-page; and the shapes of words on the page and maybe illustrations. Poetry is an art that, if it’s working, is constantly reinventing itself.

I look back at my early poems and find fault. I find myself blaming an over-voracious intake of French Surrealism; too much Kenneth Patchen one year, too much Stevie Smith the next… Too much John Berryman! And, next year, not enough John Berryman! But the ship sails on, and finds new oceans to ply.

You write in a variety of genres (poetry, non-fiction, critical writing). Do they seep into each other? Your critical writing offers the reader a freshness of vision and appraisal – not just at the level of ideas but the way you present those ideas, lucidly, almost poetically. Does one genre have a particular grip on you as a writer?

I’m only starting to realise the inter-relatedness of these different genres. A few years back I started to explore poetry’s potential to carry information, also to elaborate upon a thought in a more detailed kind of way, ie. to have an almost essayistic function. So quite a few of my longer poems (some of the odes and, particularly, ‘Memory of a fish’ in my new book) are laden with facts, figures and reasonably clearly articulated information.

Needless to say poetry infuses the writing I produce in relation to the visual arts. I find looking at art exciting; it appeals to my poetic self. I don’t really have a critical self. I hope my non-fiction writing has a cadence, a music and a subconscious (rather than a conscious) purposefulness. Pondering my recent writings on artists such as Pat Hanly, Barry Brickell and Michael Hight, I remember in each case hearing a note—a song, almost—in my ear, and I was beholden to it.

Do you think we have a history of thinking and writing about the process of poetry? Any examples that sparked you?

James K. Baxter wrote wonderfully about writing poetry. Bill Manhire’s Doubtful Sounds is an immensely useful and energising book. 99 Ways Into New Zealand Poetry is terrific too. I refer back to my set of the journal ISLANDS and, yes, it seems to me we New Zealanders have been writing about the process as well as the product. Janet Frame’s oeuvre might be our greatest, most enduring instance of writing about writing, thinking about writing, writing about thinking, and thinking about thinking.

Your poetry discussions with Kim Hill are terrific. The entries points into a book are paramount; the way you delight in what a poem can do. What is important for you when you review a book?

I think a book has to become part of your life to really make an impression. It’s the same with music or visual arts. It can’t be a purely intellectual thing, it has to take you over, to some degree. It has to be disarming. Accordingly I tend not to discuss books that don’t ‘do it’ for me. Life’s too short. Fortunately, I have catholic tastes. There are things I enjoy very much in Kevin Ireland, as there are things I enjoy in Michele Leggott. I guess this makes me a lucky guy.

I agree wholeheartedly. I am not interesting in reviewing books on Poetry Shelf unless they have caught me, stalled me (for good reasons!).

What poets have mattered to you over the past year? Some may have mattered as a reader and others may have been crucial in your development as a writer?

Two years ago I went to Paris and met up with one of my all-time heroes, the French poet and art-writer Yves Bonnefoy. He turned 90 last year (Joyeux anniversaire, Yves!) During my recent travels around the Pacific (from New Caledonia to Chile), I’ve taken bilingual editions of Yves with me everywhere. I am interested in the way he has turned the creative conundrum of being an Art Writer and a Poet into something unified and compelling (channelling earlier French poet-art-writers from Baudelaire to Apollinaire, with a nod to Yves’s near-contemporaries, that wondrous group of wanna-be French-art-poets, John Ashbery and the New Yorkers). I also took the poems of Neruda and Borges with me everywhere I went.

What New Zealand poets are you drawn to now?

New Zealand poetry is interesting at the moment. It’s all over the place. As it should be. There are plenty of people I read voraciously. As well as the poets mentioned already: Anna Jackson, Vince O’Sullivan, you Paula, Lynn Davidson, Kate Camp, Geoff Cochrane… Last year I edited a weekly column for the Best American Poets website—that was a good chance to ‘play favourites’, as Kim Hill would say. (All those posts are archived here: http://blog.bestamericanpoetry.com/the_best_american_poetry/new-zealand/) There are some great first books appearing at the moment: Leilani Tamu’s The Art of Excavation; John Dennison’s Otherwise. This bodes very well indeed.

Name three NZ poetry books that you have loved recently.

I was rereading Riemke Ensing’s Topographies (with Nigel Brown’s illustrations) the other day; I found that book very inspiring when it appeared way back in 1984. Lately I’ve also been reading Bob Orr’s crystalline Odysseus in Woolloomooloo and Peter Bland’s Collected Poems… I could go on.

Your new collection, Whale Years, satisfies on so many levels. These new poems offer a glorious tribute to the sea; to the South Pacific routes you have travelled. What discoveries did you make about poetry as you wrote? The world? Interior or external?

The Kermadec voyage, and subsequent travels—most recently to New Caledonia—opened up a huge areas of subjective experience as well as of human and natural history. How do you write about that kind of space, that energy, that life-force? Wherever you travel, the air is different; the ‘night’ has a different character; the smells and textures of the vast Pacific vary from place to place. And people move differently wherever you go – they claim a different kind of space within the environment. My recent travels have been like a door opened on a new world. The last three years of my poetry-writing have been the most intense since I was in my early twenties.

That shows in this book Greg. I am looking forward to reviewing it because it touched a chord in so many ways. I love the idea that poems become little acts of homage. What difficulties did you have as traveller transforming ‘elsewhere’ into poetry? To what degree do you navigate poetry/other place as trespasser, tourist, interloper?

The artist Robin White likes to point out that there is only one ocean on earth. All our oceans are joined together—it’s the same body of water. So, if you take the sea to be your home (which, as Oceanians, believe it or not, we should do), then as long as you’re at sea you’re still, to some degree, in your home environment.

As a poet entering a new environment, I bring with me my responses, my eye, my mind and various kinds of baggage. I’m a curious person by nature so I always want to find new things—things I don’t know anything about. I like it when my preconceptions fall apart. I love being wrong about things; I enjoy the subsidence of the known world. I quote the great post-colonialist writer Wilson Harris in Whale Years: ‘If you can tilt the field then you will dislodge certain objects in the field and your own prepossessions may be dislodged as well.’

I feel that, as a poet, I am most in my element when I am sitting on the ground and learning new things. When the field of the known has been tilted. And filling my notebooks with various tracings of that new knowledge or sensation.

This is a good way to look poetry that takes hold of you; it ‘tilts’ you. I also loved the elasticity of your language – the way a single word ripples throughout a poem gleaning new connections and possibilities. Or the way words backtrack and loop. At times I felt a whiff of Bill Manhire, at others Gertrude Stein. Yet a poem by Gregory O’Brien is idiosyncratic. Are there poets you feel in debt to in terms of the use of language?

Strangely, I can’t read Gertrude Stein anymore. She is one of a very few writers I have been in love with and then the relationship has waned. Maybe, early on, she loosened up my use of language, the extent to which the rational mind is left to run things. There was a music I found in Stein, for sure. But this was something—increasingly—I found in more conventional writers like Wallace Stevens, Robert Creeley and, most recently, in Herman Melville. Moby Dick is a piece of great, symphonic, oceanic music. The novel (for want of a better term) is an incredible noise, a racket of spoken and sung sounds. Melville’s style reminds me of all the depth-finders, radars, monitors and gauges on the bridge of HMNZ Otago as we sailed north to Raoul Island in May 2011. All that information pinging and popping…

Is there a single poem or two in the collection that particularly resonates with you?

The long poem, ‘Memory of a fish’, is the piece that connects various experiences from the three year period in which the book was written, and brings them together—in an essayistic fashion, almost. I enjoy the ebb and flow of the triplets, and the world’s details tripping along them, like things washing ashore on Oneraki Beach… When I was writing that poem I felt I was living inside it, totally. And I haven’t quite climbed out of it yet, to be honest.

The book also demonstrates that eclectic field you plunge into as a reader with its preface quotes. What areas are you drawn into at the moment? Any astonishing finds?

The quotations at the beginning of the three sections of the book are constellations in the night sky above the poetry-ground. They mark points of reference, further co-ordinates, which have guided the writing: W. S. Graham’s ‘The stones roll out to shelter in the sea.’ The Flemish proverb: ‘Don’t let the herring swim over your head.’ Those are verbal artefacts I have carried around with me, much as you would pick up a shell or a colourful leaf. They were/are talismans. So I have stored them inside the book as well. Cherished things.

‘Constellation’ is perfect. I was thinking underground roots that nourish. Or one of any number of maps you can lay over the poems (the map of domestic intrusion, the map of childhood, the map of objects, the map of reading). But yes the process of writing has its constellation-guides as you venture into and from both dark and light.

Poetry finds its way into a number of your paintings (as it does with John Pule). There are a number of drawings included in the book that add a delicious visual layer. How do you negotiate the relationship between painting and poetry? Does one matter more? Do they feed off each other?

My notebooks contain a thick broth of visual and verbal ingredients. These materials arrive in my journal simultaneously. When writing or painting, I separate the words from the visual images and work on them more-or-less separately. When it comes to putting together a book, like Whale Years, these two disparate activities are reunited again. I’ve always loved illustrated books. (I think immediately of Bill Manhire’s The Elaboration, with pictures by Ralph Hotere; Blaise Cendrars’ long Trans-Siberian poem, illustrated by Sonia Delaunay; William Blake illustrating himself, and so on)

NOTES ON THE RAISING OF THE BONES OF PABLO NERUDA AT ISLA NEGRA by John Reynolds & Gregory O’Brien, etching, 2014

You have collaborated with a number of other artists and writers. What have been the joys and pitfalls of collaboration?

There are no pitfalls, as far as I can see. Somehow, I’ve found my way into a few collaborative circumstances and very much enjoyed the results. In the past year I’ve made etchings with my two painter-friends John Reynolds and John Pule. Like Charles Baudelaire and Frank O’Hara before me, I seem to have been lucky enough to fall in with a good crowd of painters (and also photographers—but that’s another story).

SAILING TO RAOUL by John Pule & Gregory O’Brien, etching, 2012 (John titled this work, riffing off Yeats’s ‘Sailing to Byzantium’)

The constant mantra to be a better writer is to write, write, write and read read read. You also need to live! What activities enrich your writing life?

Certainly my recent travels around the Pacific have been hugely enriching. I’m not a proper swimmer, but since I was a child I have had a great passion for floating in, or being upon salt water. (My book News of the Swimmer Reaches Shore grew out of that propensity.) The everydayness of existence is the most enriching thing—as the poems of Horace and Neruda and Wedde keep reminding me. What a great and pleasant swarm of information and sensation we find ourselves amidst, every day of our lives.

Finally if you were to be trapped for hours (in a waiting room, on a mountain, inside on a rainy day) what poetry book would you read?

I keep coming back to the Collected Poems of James K. Baxter. Not because it’s the best book ever written but because of the simple fact that it occupies a huge and resonant place in my life.

Auckland University Press page

New Zealand Book Council page

Arts Foundation page

The Kermadecs page

National Radio page (discussing poetry highlights of 2014 with Kim Hill)

Friday Poem: Kerrin P Sharpe’s ‘she gets these letters’ — Nouns swell with options

she gets these letters

one moment there

is vodka at

a forest wedding

the next the last

breath of a gun

she watches defiance

secret army draws

a map of Poland

the sweep of ice

fills her throat

this is the plantation

her father was taken to

perhaps this is the pine

he walked towards

as if he spent

his mornings collecting

alpine specimens

and the snow he fell into

pages of white birds

©Kerrin P. Sharpe There’s a Medical Name for This Victoria University Press, 2014

Author bio: Kerrin P. Sharpe’s first book three days in a wishing well was published by Victoria University Press in 2012. Her work appeared in Oxford Poets 13 (Carcanet). Another book, there’s a medical name for this was published August 2014 (VUP). A third collection rabbit rabbit is in progress with a grant from Creative New Zealand.

Author note: This poem began life after I had watched the movies Defiance and Secret Army. I began thinking about the huge significance of locations and how they are changed forever when terrible crimes have been committed there. This poem was published in the NZ Listener in 2014.

Note by Paula: What draws me to this poem is the enigma and the gap. Without the back story the possibilities are myriad whether as reader you step into shoes that are autobiographical, another persona or a mix of both. There is a jostling of meaning and effect between elements; from title to poem, night to day, life to death, vodka to the last breath of the gun. Nouns swell with options: vodka, forest, the map and the plantation are nouns of elsewhere. The understatement is striking. There is the ominous ring of ‘was taken’ that is amplified by the ‘chill of ice.’ The implications of ‘as if specimens’ seems to mask from what really took place. The final image in the last two lines is utterly potent. The white snow might stand in for the clean white page, the insistence of hope, the threat of war and violence and atrocity, and the magnetic pull of the prospect of peace. For me, the word ‘sweep’ leaps out not just for the ear but semantic rewards (a clean sweep, the expanse of the scene, clearing history, fresh beginnings). This is a haunting poem. Yes, it makes a difference when you know the back story but the gaps are still profound.

Victoria University Press page

WAIHEKE POETRY FESTIVAL”IN THE AIR” 2015

WAIHEKE POETRY FESTIVAL”IN THE AIR” 2015

Guests: South Auckland Poets Collective ( SAPC NZ)

MCs: BARAKA 11 00am – 1 00pm; SUSI NEWBORN 1 30pm – 3 30pm

closing: KATY SOLJAK; featuring scheduled poets

non-smoking event, free entry, some open mic slots avail.

Where: Artworks Amphitheatre, backcourt,Waiheke Library, off Oceanview Rd, Oneroa

When: Sunday 22nd March 11 00am – 3 30pm

Poetry NZ 50th issue seeks submissions

Poetry NZ‘s 50th issue will be published later this year. Submissions are now open (closing 31st July). Please subscribe to our page for updates.

Poetry NZ is a print journal, established in 1951 by Louis Johnson, edited between 1993 and 2014 by Alistair Paterson, and now housed by Massey University. The current editor is Jack Ross.

Harry Ricketts’s Half Dark — These poems are like little retrievals from the shade of the past

Harry Ricketts, Half Dark Victoria University Press, 2015

The title of Harry Ricketts’s new poetry collection, Half Dark, is apt as many of these poems are like little retrievals from the shade of the past. Poetry as retrieval. As excavation. As reflection. The half dark underlines (as does the blurb on the back) that this collection is dedicated to the gap, and that in these spaces, there is electric life. Poetic life. One poem, ‘Gap,’ makes reference to the haunting voice of the London Underground:

‘When I grow up, I want to be

the man who says “Mind the gap”.’

Down the years how your voice,

that phrase, have haunted me.

Yet ‘mind the gap’ is also like the surrogate, underground voice of the poetry that cautions us to stall in the gap for it is there poetic rewards will multiply. If you think of the poetic gap, you are lead in myriad directions from the silent beat at the end of the line, to the white space of the page, to the tension between what the poet holds back what the poet reveals. All these things are paramount in a collection that pays diligent attention to the pause at the end of the line, the form of the poem upon the page and what is revealed by choice. Yet what animates the poems beyond this is the gap of recollection, with so many examples stretching back in time to record and review. Now the gap is the faltering stutter of history where the past is only visible in pieces and can so easily be misremembered and even diverted to suit a cause. The London-Underground echo resonates on another level when you bear in mind the punning possibilities of the word ‘mind.’ Step beyond the warning (Watch out!) to the need to tend and care for and you reach the subterranean simmer that shows these poems come from the heart. The poet loved and the poet minded.

One striking example is a triloet dedicated to Jessie. The looping lines signal the circularity of families dividing and returning, of life itself though generations of fundamental behaviour and connections. Much is not said, yet the mood that permeates is infectious and moving:

(…)

Sometimes we find ourselves quite

overcome and can’t hold back the tears,

but still we walk, talk, laugh in soft November light;

a day to set against all the lost years.

In ‘Broken Song,’ the gap is replayed on the page in the syncopated words, the white space, the withholdings paramount.

Harry has often displayed a predilection for traditional forms; they become vessels for play, for the allure and comfort of repetition, for the challenge of innovation or depth within constraint, for a contemporary licence to laud, rattle and refresh. In his endnote, Harry addresses his current preoccupation with the triolet: ‘I soon found that, like the villanelle, the restrictions and repetitions of the triolet can lead to writing poems not merely playfully or self-consciously ingenious (nothing wrong with that of course) but poems embodying confinement and the inability to break out of particular cycles of thought, feeling and behaviour.’ There are ways in which his triolets do this, as in ‘Jessie,’ yet there is often a word or phrase that acts as splinter. In this poem, for me, it is the word ‘lost’ as it becomes a universal beacon. It breaks out from the individual story (the way you can’t go back as father and son in this case) and spikes your own disconnections and connection, your own missing pieces.

Poetry also sparks on poems as startling neighbours. In some poems, it almost feels as though this intrudes on that, and that intrudes on this, to offer different insights. in ‘The Frick comes to Lake Rotoma,’ it is as though the tracing-paper museum is laid over the tracing-paper lake and you understand that purity of location is perhaps a pipe dream. Something always tugs at you elsewhere and something always keeps you heartily rooted here.

These postcards before you are meant

to bring back the Frick, that sumptuous

room, Fragonard’s Four Stages

of Love: meeting, pursuit, lover

crowned, love letters—all those pink roses,

that jaunty parasol, No,

you’re still here, sweat trickling over

your ribs. They knew love wasn’t that easy.

Perhaps, the feature that I found most admirable was the way in which many of the poems bear witness to an instance. The gaps heighten this effect along with the detail, musical choices and tropes. There is a sense that the poem frames a moment, an incident, a scene, a person (friend or family in many cases). ‘Pewsey’ is a terrific example of this, as is ’10 to 3.’ The latter again catches the circularity of life with a perfect balance of economy (the gap) and detail. The central image comes alive with a trope that evokes vulnerability, tenderness, stillness: ‘your hands bunched like spiders/ the purple eiderdown.’ The poem haunts as it exposes a moment so intimate, in its familiarity, it becomes universal.

Harry’s new collection takes you from Te Mata Peak to Frankfurt to Rome. It traverses weather, old friends and family. What marks the measure of book, is the fact there is so much one could say about the connections that emerge from the spaces. The poems are the heartbeat of a backward look; at times mourning, often contemplative, they revel in humour as much as intimacy, in sumptuous detail as much as the well-tended gap. This is Harry at his poetic best.

Victoria University Press page here

Poetry Shelf interview with Harry here

Just fabulous! Gregory O’Brien on Peter Olds and Geoff Cochrane with Kim Hill

Poetry with Gregory O’Brien: Peter Olds and Geoff Cochrane

Originally aired on Saturday Morning, Saturday 7 March 2015

Painter, poet, curator and writer Gregory O’Brien discusses You Fit the Description: the Poetry of Peter Olds and a new collection by Geoff Cochrane, Wonky Optics.

Listen here