Poetry Shelf noticeboard: Launch of Ash Davida Jane’s How to Live with Mammals

Leave a reply

Indicator

All through thin winter

a single yellow-lipped flower

hangs like honeydrip

from the tip of a twig

on the kowhai outside our window.

Now and then a wax-eye

or an eerily silent tūī slips by,

suckles there, each visit so swift

we soon guess the teat’s run dry:

no languid glug of nectar

like those summer-dusty kids,

canter-and-cartwheel parched

at the schoolyard drinking fountain,

when their every mouthful sounds

a grateful, gulping hum

like the rev of a warming engine.

Through ice, hail and fog

this blossom that grips the brink

seems bitter, withered emblem

of what is not; of tense lockdown;

of what cost; futures lost,

the tired earth’s toxin-clogged, wild demise

I even cuss some fossicking birds

as if they’re mad deniers —

boom-times are gone.

Can’t you just goddamn leave

that last poor scrap alone?

Then one cold but blueing morning

I lift the kitchen blind

wait for coffee to send its sun

through the hoar-frost of sleep

to see the whole tree

buckets with its own bright rain

a thousand beak-mouthed flowers

sing the aria of themselves

as if that one yellow blossom

in its winter death clench

was the stoic pilot light

that set the whole tree ablaze

a Kali-armed candelabra

peacocking with gold —

yet this silken dart and glitter

of unbidden happiness —

now grown so unfamiliar —

is it dangerous?

What have I turned my back on

for that moment

it takes a small child

to rush before a speeding van,

slip into an unfenced pool,

for some link in the web to fray

by the time night flows over the tree

as dark as the inside of a body?

Emma Neale

Emma Neale is a Dunedin based writer and editor. The author of 6 novels and 6 collections of poetry, Emma is the current editor of Landfall.

Go here for details (tickets are free)

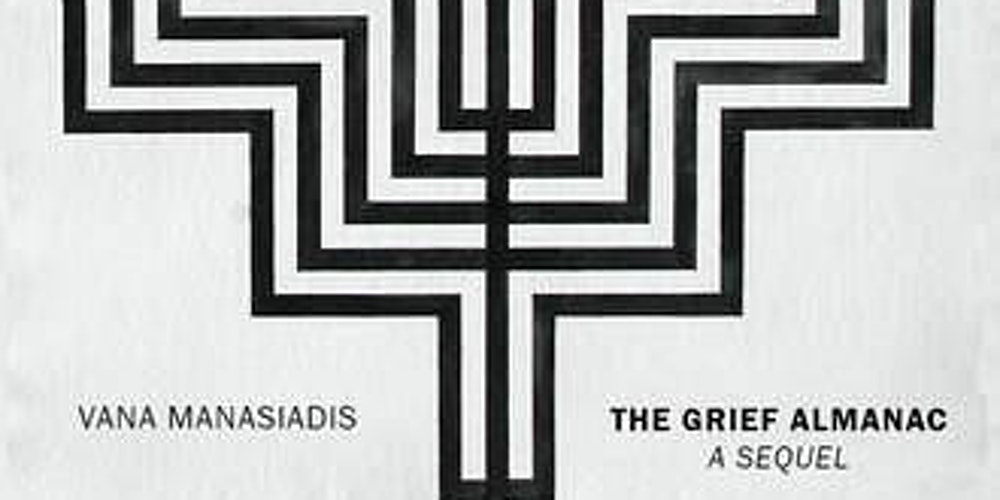

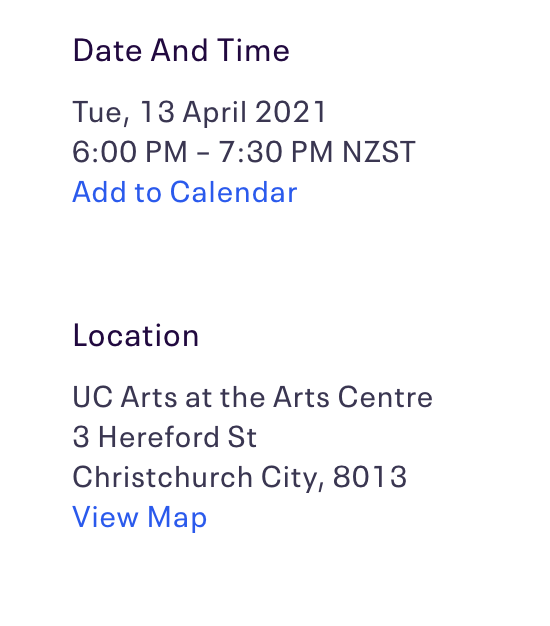

λυρικό ελεγείο : Vana Manasiadis in conversation with Nicholas Wright

This is the first in our An Evening With Series, hosted at UC Arts at the Arts Centre Christchurch.

Vana Manasiadis’s The Grief Almanac: A Sequel (2019) is, as the title of this talk suggests, deeply involved with the forms of lyric and elegy. Indeed, her volume has been described as a “hybrid of poetry, memoir, letter, essay and ekphrasis” that pushes at the boundaries of poetic form “melding Greek with English, prose with poetry, and the past and present with fantasy and myth”. Do come along to hear Vana talk about the poems in this volume, her thoughts on poetic form, as well as the new work she is writing as Ursula Bethell Writer in Residence, in the University of Canterbury’s English Department.

———————-

Vana Manasiadis is a Greek-New Zealand poet and translator who has been moving between Aotearoa and Kirihi Greece the last twenty years. Her most recent book The Grief Almanac: A Sequel, followed her earlier Ithaca Island Bay Leaves: A Mythistorima in experimenting with hybridity and pluralism and is being translated into Greek for forthcoming publication in Greece. She has also edited and translated Ναυάγια/Καταφύγια Shipwrecks/Shelters, a selection of contemporary Greek poetry, and co-edited a bilingual volume of poetry, Tatai Whetu, Seven Māori Women Poets in Translation, a Spinoff ‘20 Best Poetry Books of 2018’, with playwright Maraea Rakuraku. Her residency project will include an exploration of translanguage and poetic form, of territory and authority. She will be working on poetic texts in response to various geographies of Christchurch and Canterbury, and on a series of multilingual and multimodal dialogues between exiled speakers.

Nicholas Wright is a lecturer in the English Department, University of Canterbury. He has published on a host of New Zealand poets, and is currently working on a book of essays on the contemporary lyric in Aotearoa.

reading the signs Janis Freegard, The Cuba Press, 2020

I walk into Ema Saikō’s room to find the poet herself at the writing desk,

long hair scraped back in a bun. She wears an embroidered robe. Tea? I

offer. It seems the right thing to do.

I let her choose the teapot. I was tossing up between late evening

blue and bright green. She claps her hands and says something about

bamboo. So I go with the green one that looks like a Dalek.

from ’11. Meeting Ema Saikō’

I have been musing on national book awards and how they expand the life of shortlisted books and boost the authors and boost readership. Without a doubt they are a vital and important part of book landscapes. But like so many people, I find the idea of a ‘best’ book a little twitchy. I flagged the 2021 Ockham NZ Book Award poetry longlist as the best I have seen in ages, especially because (for once) it wasn’t top heavy with Pākehā poets. I had read, reviewed and adored eight of the books and then read, reviewed and adored the other two. If you haven’t read these fabulous books check them out. Yet there are other nz poetry books I have read, reviewed and adored that didn’t make the long list. Slowing down with a poetry book, finding the ways your body, heart and mind absorb the poetic affects is a privilege. A joy. As both author and reader I claim the writing and reading process as the most important thing.

A book has the ability to lift you.

I have been reading Janis Freegard’s poetry collection reading the signs over the past months and falling in love with the way it inhabits the moment. Janis had been awarded a residency at the Ema Saikō room in the Wairarapa. This room and the rituals Janis observed were the springboard for a sequence of connected poems.

Halfway through the book I became curious about Ema Saikō (1787 – 1861). She was a Japanese poet, painter and calligrapher much influenced by Chinese art, and who was producing work at a time when it was rare for women to do so (publicly anyway). I know nothing about her beyond her attachment to the physical world. But I am curious about the bridge from this much lauded woman to the occupants of a room named after her. It seems like Janis was also curious about Ema as her poetry and her occupation of the room become more and influenced by the poet / painter from the past. In both writing and in observing daily rituals such as making tea, especially in the making of loose-leaf tea with an exquisite concentration, Janis moves closer to Ema.

While you’re drinking the tea,

only drink the tea. By all means

notice twig shadows fluttering on the ground,

the calls of kiwi and kākā,

but do nothing else with your hands.

Let drinking the tea be the whole of it.

from ‘4. If you’re looking for a teapot, make sure

there’s a lug on the lid’

Janis writes after a fracture in her life, mending herself by writing poetry, paying attention to what is close at hand. A gender-fluid interpreter arrives in the sequence to direct her attention to things, questions, possibilities. Poetry stands in for the gold that ‘seals the fissures’:

You’ll break until you feel you may never be whole again.

(You will be.)

But you’ll be altered. Now is the time for kintsugi,

the Japanese art of repairing with gold, mending the cracks

in smashed ceramics to make something more beautiful.

You’ll reassemble yourself and use gold to seal the fissures.

from ‘8. Kintsugi’

So you could see this sequence as therapeutic, and no doubt it is, but it transcends the therapeutic and becomes a mesh of experiences: of slowing down and taking note of, of absorbing beauty in nature, from the sky to birds to trees. She is reading the sky – and the way a poem is a tree and a tree is a poem. She is reading the tea. She is absorbing stages of grief and loss and peace and life. She is translating what she feels, thinks, observes into lyrical poetry that is both steadfast and ethereal.

Ema Saikō says, ‘It is true things get lost in translation, but if you lose so much more if you don’t translate at all.’ In a sense Janis is translating herself on the line, finding lyrical form for experience, memories, feelings, contemplation. She is translating myriad connections with the world, with life – with an endangered world, with an endangered self.

It is warming to read, this book of dreaming, of signs, of being. I imagine it as a prism in the hand that shifts in the light. And here is the thing. I am never after the best book. I am after the prismatic effects that poetry has upon me, the way a book can shift and glint in my heart and mind as I read. Think how the effect changes with each book you pick up. The way it lifts you off the ground and out of daily routine and then returns you to your own daily rituals observations concentrations. An exquisitely layered and fluent book that reminds you of the power of the moment. I loved this book.

Janis Freegard is a Wellington poet, novelist and short story writer. She has won a number of awards including the Geometry | Open Book Poetry Competition and the BNZ Katherine Mansfield Short Story Award, and she was the inaugural Ema Saikō Poetry Fellow in the Wairarapa. Janis performs with the Meow Gurrrls poetry collective.

The Cuba Press page

Janis Freegard’s Weblog

VIDEO: Janis reading poems from reading the signs (Wellington City Libraries)

Janis held the inaugural Ema Saikō Poetry Fellowship with NZ Pacific Studio in Wairarapa. The 2015 Fellow: Yukari Nikawa (Japan); 2016: Alan Jefferies (Australia) and Ya-wen Ho (NZ); 2017: Makyla Curtis (NZ); 2018: Leanne Dunic (Canada); 2019/2020: Rebecca Hawkes (NZ). For more

Photograph by Catherine Chidgey

Listen here to Tracey Slaughter’s invigorating conversation with Jesse Mulligan (music, books, writing, solitariness, collaboration, a new short-story collection). And thanks for the Poetry Shelf nod! Meant a lot. Especially love hearing the books that make us (Marguerite Duras’s ‘quicksilver’ sentences!). Excellent music choices to hunt down too.

Ten things I love

Me in Beijing, taken by my partner.

a dream of foxes

in the dream of foxes

there is a field

and a procession of women

clean as good children

no hollow in the world

surrounded by dogs

no fur clumped bloody

on the ground

only a lovely line

of honest women stepping

without fear or guilt or shame

safe through the generous fields.

Lucille Clifton

Full poem and video at poemhunter

“First Love / Late Spring” by Mitski, from her album bury me at makeout creek.

A song I listened to while beginning to write the book in Shanghai.

A bathful of kawakawa and hot water by Hana Pera Aoake (Compound Press).

Minari

Five Mile Bay, Lake Taupō, my first swim after arriving back in Aotearoa.

Char kuay teow and sweet milk tea.

A window.

Next to the windowsill where I’ve planted daffodils, in the sun, the cat perched next to me.

Night train to Anyang

light changes as we cross into neon clouds

voices flicker through the moving dark

like dream murmurs moving through the body

red and silver 汉字 glow from building tops

floating words I can’t read rising into bluest air

they say there are mountains here but I can’t see them

there are only dream mountains high above the cloudline

I come from a place full of mountains and volcanoes

I often say when people ask about home

when I shut my eyes I see a ring of flames

and volcanoes erupting somewhere far away

when I open my eyes snow is falling like ash

Five questions

Is writing a pain or a joy, a mix of both, or something altogether different for you?

Writing gives me adrenaline, which is sometimes a kind of joy, or at least relief. Writing –when it’s going well – gives me energy in the moment itself, but often leaves me utterly drained.

Name a poet who has particularly influenced your writing or who supports you.

There are so many poets who have supported me and deeply influenced me; it wouldn’t be fair to name just one. I am endlessly grateful to poets Alison Wong, Helen Rickerby, Anna Jackson, Bhanu Kapil, Sarah Howe and Jennifer Wong – I walk in their footsteps.

Was your shortlisted collection shaped by particular experiences or feelings?

The book is so distinctly shaped by a particular period in my life. Some poems feel ancient to me now, distant and far away – but I don’t mind that. I was living in Shanghai, my first time living alone, feeling both brave and terrified at the same time. The poems are shaped by isolation, longing, aloneness (but not always loneliness) and in-betweenness.

Did you make any unexpected discoveries as you wrote?

Always – I think this is how writing works for me. I have a loose outline in my mind of something I want to get down on the page, usually starting with a particular image, and then the writing itself reveals to me the place I want to go. I can’t quite explain how it happens, only that I’m following threads, making connections as I go. When something unexpected happens, I think that’s when I’ve written something good.

Do you like to talk about your poems or would you rather let them speak for themselves? Is there one poem where an introduction (say at a poetry reading) would fascinate the audience/ reader? Offer different pathways through the poem?

I prefer to let the poems do the work, although I enjoy giving some background details about some poems, such as “The First Wave”, which was written while listening to the online livestream of Radio NZ while I was in Shanghai at the time of the Kaikoura earthquake in 2016. Or, “The Great Wall”, which I affectionately call my Matt Damon poem, titled after the 2016 movie of the same name.

Nina Mingya Powles is a poet, zinemaker and non-fiction writer of Malaysian-Chinese and Pākehā heritage, currently living in London. She is the author of a food memoir, Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai (The Emma Press, 2020), poetry box-set Luminescent (Seraph Press, 2017), and several poetry chapbooks and zines, including Girls of the Drift (Seraph Press, 2014). In 2018 she was one of three winners of the inaugural Women Poets’ Prize, and in 2019 won the Nan Shepherd Prize for Nature Writing. Magnolia 木蘭 was shortlisted for the 2020 Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Nina has an MA in creative writing from Victoria University of Wellington and won the 2015 Biggs Family Prize for Poetry. She is the founding editor of Bitter Melon 苦瓜, a risograph press that publishes limited-edition poetry pamphlets by Asian writers. Her collection of essays, Small Bodies of Water, is forthcoming from Canongate Books in 2021.

Nina reads ‘Faraway love’ from MAGNOLIA 木蘭

Review on Poetry Shelf here

Seraph Press page

Nina’s website

MAGNOLIA 木蘭, Nina Mingya Powles, Seraph Press, 2020

AUP New Poets 7 features the work of Rhys Feeney, Ria Masae and Claudia Jardine. The series is edited by Anna Jackson.

Editor Anna Jackson suggests the collection ‘presents three poets whose work is alert to contemporary anxieties, writing at a time when poetry is taking on an increasingly urgent as well as consolatory role role as it is shared on social media, read to friends and followers, and returned to again in print form’.

I agree. Poetry is an open house for us at the moment, a meeting ground, a comfort, a gift, an embrace. But poetry also holds fast to its ability to challenge, to provoke, to unsettle. In the past months I have read the spikiest of poems and have still found poetry solace.

AUP New Poets 7 came out in lockdown last year and missed out on a physical launch. To make up for that loss I posted a set of readings from the featured poets. One advantage with a virtual celebration is a poetry launch becomes a national gathering. I still find enormous pleasure in online readings – getting to hear terrific new voices along with old favourites.

Herein lies one of the joys of the AUP New Poets series: the discovery of new voices that so often have gone onto poetry brilliance (think Anna Jackson and Chris Tse).

Rhys Feeney is a high school teacher and voluntary health worker in Te Whanganui-a-Tara with a BA (Hons) in English Literature and a MTchLrn (Secondary). Ria Masae is an Auckland-based poet, writer and spoken-word artist. In 2018 she was the Going West Poetry Slam champion. Claudia Jardine is a Pākehā/ Maltese poet and musician with a BA in Classics with First Class Honours. The three poets have work in various print and online journals.

Rhys Feeney

I am thinking poetry is a way of holding the tracks of life as I read Rhys’s sequence of poems, ‘soy boy’. He is writing at the edge of living, of mental well being. There is the punch-gut effect of climate change and capitalism. There are crucial signals on how to keep moving, how to be.

The poems are written as though on one breath, like a train of thought that picks up a thousand curiosities along the way. As an audio track the poetry is exhilarating in its sheer honeyed fluency. Poems such as ‘the world is at least fifty percent terrible’ pulls in daily routine, chores, political barbs. The combination matters because the state of the world is always implicated in the personal and vice versa. The combination matters in how we choose to live our lives and how we choose to care for ourselves along with our planet.

waking up from a dream abt owning a house

for a moment i think i’m in utopia

or maybe australia

but then i see the little patches of mould on the ceiling

i roll over to check my phone

but i forgot to put it on charge last night bc i was too tired

why am i am so fucking tired all the time

i should find some better alternative to sugar

i should find some better alternative to lying there in the morning thinking

Artificial Intelligence is a Fundamental Risk to Human Civilisation

or what i am going to have for breakfast

how can i reduce my environmental footprint

but increase the impact of my handshake

from ‘the world is at least fifty percent terrible’

I love the way Rhys plays with form, never settling on one shape or layout; the poems are restless, catching the performer’s breath, the daily hiccups, the unexpected syncopation. Words are abbreviated, lines broken, capitals abandoned as though the hegemony of grammar and self and state (power) must be wobbled. Yet I still see this as breath poetry. Survival poetry.

I am especially drawn to ‘overshoot’; a poem that lists things to do that get you through the day, get you living. The list is more than a set of bullet points though because you get poignant flashes into a shadow portrait, whether self or invented or borrowed.

5) give yourself time to yourself

light fresh linen candles

& cry in the bath

call it self-care

6) eat a whole loaf of bread in the dark

7) start working again

the topsoil of your tolerance is gone

you break in two days

this is called a feedback loop

your coping strategies don’t work

in this new atmosphere

Rhys’s affecting gathering of poems matches rawness with humour, anxiety about the world with anxiety about self. Yet in the bleakest moments humour cuts through, gloriously, like sweet respite, and then sweesh we are right back in the thick of global worry. How big is our footprint? What will we choose to put in our toasters? Have we ever truly experienced wilderness other than on a screen? This is an energetic and thought-provoking debut.

Ria Masae

What She Sees from Atop the Mauga opens with a wonderful grandmother poem: ‘Native Rivalry’. The poem exposes the undercurrents of living with two motherlands, Samoa and Aotearoa, of here and there, different roots and stars and languages, a sea that separates and a sea that connects. There is such an intense and intimate connection in this poem that goes beyond difference, and I am wondering if I am imagining this. It feels like I am eavesdropping on something infinitely precious.

i tilted my face up to the stars

that were more familiar to me

than the ones on Samoan thighs.

without turning to her, i answered

‘Leai fa‘afetai, Nana.’

i felt her stare at me for a long pause

before puffing on her rolled tobacco.

we sat there silently looking at the night sky

until we were tired and went to sleep

side by side on a falalili‘i in her fale.

from ‘Saipipi, Savai‘i, Samoa’ in ‘Native Rivalry’

Perhaps the lines that really strike are: ‘Mum was fa’a pālagi, out of necessity / i was pālagified by consequence / so, was i much different?’

I am so affected reading these poems on the page but I long to hear them sounding in the air because the harmonics are sweet sweet sweet. ‘Intersection’ is an urban poem and it is tough and cutting and despairing, but it is also stretching out across the Pacific Ocean and it is as though you can hear the lip lip lap of the sea along with the throb throb throb of urban heart.

She sits at her window

staring down at the city lights.

Her scared, her scarred, her marred wrists

hugging her carpet-burnt knees.

The waves in her hair

no longer carry the scent of her Pacific Ocean

but burn with the stink of

roll-your-own cigarettes.

Ah, enter these poems and you are standing alongside the lost, the dispossessed, the in-despair, you are pulled between a so often inhumane, concrete wilderness and the uplift and magnetic pull of a Pacific Island. I find these poems necessary reading because it makes me feel but it also makes me see things afresh. I know from decades with another language (Italian) some things do not have a corresponding word (for all kinds of reasons). ‘There is No Translation for Post-Natal Depression in the Samoan Language’ is illuminating. There is no word because of the Samoan way: ‘be back home that same evening / to multiple outstretched brown hands / welcoming the newborn baby into the extended alofa.‘ How many other English words are redundant in a Samoan setting, where ‘isolation’ and ‘individualism’ are alien concepts?

At this moment, in a time I am so grateful for poetry that changes my relationship with the world, with human experience, on the level of music and connections and heart. This is exactly what Ria’s collection does.

Claudia Jardine

Claudia Jardine’s studies in Ancient Greece and Rome, with a particular interest in women, have influenced her sequence, The Temple of Your Girl. I was reading the first poem, ‘A Gift to Their Daughters: A Poetic Essay on Loom Weights in Ancient Greece’, in a cafe and was so floored by the title I shut the book and wrote a poem.

The sequence opens and closes with the poems inspired by Ancient Greece and Rome, with a cluster of contemporary poems in the middle. Yet the contemporary settings and anecdotes, the current concerns, permeate. There is sway and slip between the contemporary and the ancient in the classical poems. History isn’t left jettisoned in the past – there are step bridges so you move to and fro, space for the reader to muse upon the then and the now. The opening poem, ‘A Gift to their Daughters’, focuses on the weaving girls/women of ancient Greece, and the threads (please excuse the delicious pun) carry you with startle and wit and barb. I am musing on the visibility of the work and art women have produced over time, in fact women’s lives, and the troublesome dismissal of craft and the domestic. Here is a sample from the poem which showcases the sublime slippage:

Weaving provided women with a means to socialise and help one

another, strengthening their own emotional associations to the oikos and

to textile manufacturer itself.

The school is filled with Berninas, Singers, Vikings and Behringers.

Our mums are making cat-convict costumes for the school musical,

a mash-up of plagerised Lloyd Webber and local gossip.

I already hate CATS – The Musical.

from ‘The Importance of Textile Manufacture for the relationship of Women’ in ‘A Gift to their Daughters’

These lines reverberate: ‘My dad is furious when I decide to take a textiles class in Year 10. My mother has a needle in her mouth during this conversation.’ The characters may be fictional or the poet’s parents but the contemporary kick hits its mark. How many of us know how to sew? How many of us were frowned upon for selecting domestic subjects at secondary school? So many threads. The speaker / poet muses on ‘all the queens on Drag Race who do not how to sew’.

At times the movement between then and now borders on laugh-out-loud surprise, but then you read the lines again, and absorb the more serious prods. I adore ‘Catullus Drops the Tab’. Here is the first of two verses (sorry to leave you hanging):

there were no bugs

crawling under his skin

where that Clodia

had dug her nails in

rather

The middle section gets personal (or fictional in a personal way) as the poems weave gardening and beaching and family. Having read these, I find they then move between the lines of the classical poems, a contemporary undercurrent that contextualises a contemporary woman scholar and poet with pen in hand. I particularly love ‘My Father Dreams of His Father’ with its various loops and lyricisms.

My father dreams of his father

walking in the garden of the old family homestead at Kawakawa Point

I have not been back since he passed away

As decrepit dogs wander off under trees

to sniff out their final resting places,

elderly men wait in the wings

rehearsing exit lines.

Claudia’s sequence hit a chord with me, and I am keen to see a whole book of her weavings and weft.

Anna Jackson’s lucid introduction ( I read after I had written down my own thoughts) opens up further pathways through the three sequences. I love the fit of the three poets together. They are distinctive in voice, form and subject matter, but there are vital connections. All three poets navigate light and dark, self exposures, political opinions, personal experience. They write at the edge, taking risks but never losing touch with what matters enormously to them, to humanity. I think that is why I have loved AUP New Poets 7 so much. This is poetry that matters. We are reading three poets who write from their own significant starting points and venture into the unknown, into the joys (and pains) of writing. Glorious.

Poetry Shelf launch feature: Claudia, Rhys and Ria talk and read poetry

Auckland University page

Review at ANZL by Lynley Edmeades

Review at Radio NZ National by Harry Ricketts

I woke in the middle of the night with an @RNZ earthquake message and held the radio to my ear until dawn, drifting in and out of advice, alerts and individual stories from mayors and locals, with the anxiety like a snowball gathering Covid-level talk and Covid -rule breakers, and the incomprehensible news of threats against Muslims in Christchurch, and the brutality in women’s prisons, and the bullies in the police force, and how some people should not get airspace their behaviour and views are so damaging and ugly, and I am thinking how lucky I was to have those five days up north with my family at Sandy Bay, and food in my cupboards, and a stack of poetry books to read and review, and clean notebooks for my secret projects, and panadol for pain, and the tomato plants still laden, and water in the tank, and @ninetonoon with Kathryn Ryan keeping us posted with @SusieFergusonNZ and her heartwarming Te Reo Māori.

Poetry is the lifeline, the hand held out, the music in the ear, the saving grace, the little miracle on the page.

I reread Fleur Adcock’s The Mermaid’s Purse at Sandy Bay and this morning I was picturing myself back under the tree’s shade with the tide coming in, and the sun shining bright. I was back in the beach scene and back in the scenes of Fleur’s glorious poetry. Here is a sample from my review for for Kete Books:

The Mermaid’s Purse moves between places with vital attachments (New Zealand and Britain) and, in doing so, moves through the remembered, the felt, the imagined. I sit and read the collection, cover to cover, on holiday beside the dazzling ocean and white Northland sand. I am reading ‘Island Bay’, a poem near the start of the book and keep moving between the dazzle of Adcock’s lines and the dazzle of the sea. Here are the first two stanzas:

Bright specks of neverlastingness

float at me out of the blue air,

perhaps constructed by my retina

which these days constructs so much else,

or by the air itself, the limpid sky,

the sea drenched in its turquoise liquors

Both lucid and luminous, this exquisite poem sets the mind travelling. I’m reminded these poems were written in an old age. “Neverlasting” is the word that unthreads you. It leads to the infinite sky, and then to the inability of the ocean and life itself to stay still or the same, to old age.

Full review here

The finalists in the 2021 Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry are:

Funkhaus by Hinemoana Baker (Victoria University Press)

Magnolia 木蘭by Nina Mingya Powles (Seraph Press)

National Anthem by Mohamed Hassan (Dead Bird Books)

The Savage Coloniser Book by Tusiata Avia (Victoria University Press)

Full shortlist and judges’ comments here.

“Poetry collections published in Aotearoa in 2020 show a wealth of exceptional and original work. It’s an exciting situation for New Zealand poetry. The four shortlisted collections are striking, all exhibiting an acute global consciousness in difficult times,” says Poetry category convenor of judges Dr Briar Wood.

I was so excited about the poetry longlist, I spent the last few months celebrating each poet on the blog. What sublime books – I knew I would have a flood of sad glad feelings this morning (more than on other occasions) because books that I have adored were always going to miss out. I simply adored the longlist. So I am sending a big poetry toast to the six that didn’t make it – your books will have life beyond awards.

I am also sending a big poetry toast to the four finalists: your books have touched me deeply. Each collection comes from the heart, from your personal experience, from your imaginings and your reckonings, from your musical fluencies. The Poetry Shelf reviews are testimony to my profound engagement with your poems and how they have stuck with me.

Over the next weeks I am posting features on the poets: first up, later this morning, Tusiata Avia.

Mary and Peter Biggs CNZM are long-time arts advocates and patrons – particularly of literature, theatre and music. They have funded the Biggs Family Prize in Poetry at Victoria University of Wellington’s International Institute of Modern Letters since 2006, along with the Alex Scobie Research Prize in Classical Studies, Latin and Greek. They have been consistent supporters of the International Festival of the Arts, the Auckland Writers Festival, Wellington’s Circa Theatre, the New Zealand Arts Foundation, Featherston Booktown, Read NZ Te Pou Muramura (formerly the New Zealand Book Council), the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, the Featherston Sculpture Trust and the Kokomai Arts Festival in the Wairarapa. Peter was Chair of Creative New Zealand from 1999 to 2006. He led the Cultural Philanthropy Taskforce in 2010 and the New Zealand Professional Orchestra Sector Review in 2012. Peter was appointed a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for arts governance and philanthropy in 2013.