Doing my blogs in lockdown is both kite and anchor, a way to push Covid-19 anxiety to one side and focus on the way words sustain, delight, energise. But some days I step into bottomless dark holes and it is much harder to find the ladder leading to the light. Ah! Then like a small miracle, I pick up a new poetry book, jot down entry points, sort a new post, come up with new, challenging ideas. My blogs keep rolling, my secret writing keeps rolling, and each day is a gift.

Everyone copes with lockdown differently, both in terms of calls for caution and calls for freedom. Some writers have stalled, while others find words flowing onto the page. I decided to create a space for writing in lockdown, in Tamaki Mākaurau, Te Tai Tokerau and Kirikiriroa, inviting writers across all genres to contribute a small text. The subject matter and style were open, with a maximum of around 400 words. Rather than a piece of writing from me, I have included photographs I’ve taken since August 17th in my privileged rural lockdown haven (plus a few photos I noted by others).

Thanks to everyone who contributed! Keep safe, stay strong, and tend the connections.

Aroha nui,

Paula

Zoom (Sep 18, 2021)

Today

every poem that could ever be written

is nesting in my body.

Poems in the dipping curve

of the black wings I watch in the air

as I sip my morning coffee,

Spring: green leaved balcony.

Elevated.

A cloudless blue sky holds light for me.

Open arms.

Poems unfold from their resting place

where they have been waiting to be written,

so soft and patient.

They take flight

birds in the sky,

whirling dervishes

of black divinity.

Fluttering

heart-beated whirs

of feathered feelings,

so light –

their wide winged

dark

in clarity blue.

Grace.

There is poetry to be found, even in

the single slow-moving plane,

lumbering, linear,

able to carry its weight

in only one direction.

How limited the flight paths are,

that we dream of –

for ourselves,

as human.

And yet, still,

this man-made craft

has pushed past gravity.

Imagined creature.

It has made its way out of our minds

into the sky.

Flight.

My body too,

this morning,

holds

all of it.

The engineered crafts

of man-made dreams

swimming in their straight lines in the sky

against all the odds.

Small acts of creation.

The swirling freedom of feathered movement

miracles of imagination

that preceded us –

all that we are –

dreamed up

by a universe

intelligent enough

to create us.

They still do their thing in the sky.

Everyday.

Flight.

My body too,

this morning,

transcending the limits

of three dimensional physics.

Arriving in this air, astral,

against all forces of gravity.

I sweep across this skyline

travelling in a hundred thousand soft particles,

moving both in curves

and straight lines.

Expanding.

Karlo Mila

Joanna Li

Written/spoken by Simone Kaho, music created/produced by Joanna Ji

A Suburban Miracle

The sun saunters down below the horizon and we’re walking home

and it’s springtime. Yesterday was a study in grey. The sky met

with no resistance. Today, is defined lines. Turquoise blue cracking

through eggshells, a strike of sun against the wind. We cross above

the southwestern motorway and admire the four-lane traffic, tutting

at the revved-up engines as they zip from lane to lane with no flash

of an indicator. And it’s just this—over and over again. The ruby-red

stop signs, peeling white paint. The pylon’s standing with their hands

on their hips. Every car radio distorting the breeze. I pull at my jumper,

tug the sleeves down over my fists, just to have something to do with

my hands. The air isn’t cold—it feels like summer. And we keep

walking, like spring has just begun, like we haven’t really missed it.

There are these little yellow flowers that seem to have just bloomed

over the bus stop. They litter the path like lost coins. And up above—

a suburban miracle. Hiding amongst the new leaves, these three sleek

parrots. Red-headed beauties, with their lime green bodies, their blue

kite tails. They take my breath away. I mean, the audacity. They shouldn’t

be here, perched so casually in a tree, on the side of the main road. But

they are. And it feels like a sign—like I haven’t been paying enough

attention. When we reach home, I pause at the letterbox, spin around and

look back at the distance travelled. There isn’t much light left but it’s

steady, and there’s a bus coming up over the hill and tomorrow, nothing

will touch me.

Brecon Dobbie

28 Phrases of the Moon: a lockdown almanac

- The state of the moon makes itself known every night.

- If they can send one man to the moon, why can’t they send them all?

- The same force binds the fridge magnet to the fridge that binds the moon to the earth.

- The dark side of the fridge where many cockroaches cavort.

- Mooning around the fridge, finally you open the door to find someone has already eaten . . .

- That someone turns out to be you. You go outside, moonrise behind the roof.

- If the cow jumped over it, is that why cows say moo?

- What was it Rona said, that landed her on it forever?

- Self-improvement: go online, learn how the moon pulls the tides.

- Neap and ebb, blood and spring, wax and wane, full and new, gibbous and blue.

- Invisible forces pull us, invisible microbes invade us, visible billionaires dismay us.

- Scotty beamed him up and he fell back to earth with moonbeams on his face.

- Ko koe he haeata o te marama

- And I the moon present

- Breakfast in Glen Eden music: ‘There’s such a lot of world to see . . . My huckleberry friend’ sings Louis.

- Something fishy about having your moon in Pisces.

- Day 17 is the time for planting new ideas in an old notebook.

- The moon wags her tail – naughty moon!

- Craters full of dark and light and seas full of nothing but names.

- Lots of good things come out of idiocies, said Federico Fellini – hurray for lunatics!

- Surface, lunar, probe, module, touchdown, the day begins to fill with names.

- Dinner Music in Glen Eden: Hirini sings: ‘Whiti te marama i te pō . . . te mata o te pō’

- If you believed your senses, you’d think sun and moon the same size.

- Better to be an honest liar than a dishonest truthteller.

- Everyone begins to look like the moon – I could be anyone.

- The new moon’s arms, the cradle in which, old moon, you lie.

- The moon has slim ankles, shapely calves and strong thighs

- and she dances – at least she did last night.

murray edmond

To the North

Sure, we’re damned to piles and cold showers

sometimes, wind rattling the screen netting

like it’s some far off island—not just past

the bridge. A gust here makes the house flutter

wings and feathers perch a song from the tips

of branches. Pulled apart like batting, hung

in the trees like ash, the pese ma le aufaipese

plays on loop chanting, praying the betrayal

back towards memories and McDonalds ready

for the next car load over the bridge. It’s bent

until we get on, the rise and fall sloping the city

behind us—hard neon lights, chocolate foil

wrappers litter the Waitematā—the mud prints

at the bottom already filled with gummy water

and loose scales. I’ll never dive in even if I want

the vertigo. Seems way easier when the bridge

arcs a horny spine and we brake at the peak only certain

of the Vā shifting with us like a me -mbrane.

Are we nucleus? Well, we’re family now. The boot

door half-closed over our Kmart bookcase

wind rushing in from the back, fingers lemon

from gripping the cackling MDF.

A car passes us and the old woman up front

tracks the sucking wind all up my nape, my

god the eyes are sticky here: pudgy, sour, crusty

oyster shells drummed with a knife

piled high above the water and sniffing hooked

lips at the cars driving back to the other side.

Amber Esau

Almost time

After daylight savings starts, the art gallery clock is out of time. At five o’clock, the clock strikes three. At two, it offers nine. At eleven o’clock, it chimes twenty-two times. The clock is not just out of sync, the wrongness of the time is different every hour. It’s only a clock, soothes my boyfriend, but I am irrationally troubled, some inner Hamlet treading the stairs of my mind at all hours, intoning the time is out of joint.

*

We left London in a hurry, because time was, as they say, of the essence. We left a Victorian flat with a clothes moth problem and a path by the river and a thousand trains that came when they said they would. We left very early in the morning with our lives in our suitcases in our hands. The light was half-asleep. We left stopped time for moving time, the pace of Auckland shockingly alive after so many months of nothing. But time is circular. Now, we sit in our front room and look out over the art gallery, where nothing and no one is moving, and watch through the window of our phones a London where the light is completely awake.

*

The first week of September. The magnolias flare white and vanish. In Albert Park, they are planting poppies in the beds, orange and yellow and pink, casting fine, clumsy shadows over each other like thoughts. The first week of October. The trees are greening over the university: Symonds Street growing its fringe out. The cherry trees flicker and fizz. The first week of November. I lie on a picnic mat, buttered by the sun, until I fall asleep and burn. Later, I soothe my shoulders with aloe. They are so bright in the mirror, they look urgent, raw with meaning. The seasons do not care for us — but then, they never did.

Maddie Ballard

77 Days

When I was at high school my Russian teacher, Mr. Meijers, told us a Chekhov story, “The Bet.”

A rich man wagers a poor one he can’t spend five years in solitary confinement without going crazy. He can ask for books, or fancy food, or anything else he wants – but he’s not allowed to talk to anyone, or go outside his room.

I do remember wondering what all the fuss was about. A few years on your own, with books and entertainment of your choice – what could be wrong with that? In fact, after that, every time I bought a book I had that in the back of my mind – being stuck in my own room under house arrest.

As the years roll by, the man in the room studies languages and learns new skills; he leaves little notes asking for more textbooks. What he isn’t told is that his host has lost most of his money, and can no longer afford to settle the bet without going bankrupt.

The rich man lives in fear of his former friend.

The night before the five years are up, the man in the room escapes through a window, leaving no note behind. Perhaps he’s found out about the loss of his friend’s fortune, and decided to let him off out of pity. Perhaps all these years of enforced confinement have finally taken their toll.

Five years is an awfully long time – a scarcely conceivable weight of days. Until now, that is.

Our present lockdown, the fourth for Tāmaki Makaurau, began at midnight on Tuesday, 17th of August. As I write, at the beginning of November, only 77 days have actually gone by. But five years adds up to – give or take a leap year or so – 1824 days!

That’s almost 24 times what we’ve had to put up with so far.

And what have I done with this time?

I boxed up my father’s remaining books and carted them across the road for a church fundraiser.

I edited a webfestchrift for my friend Michele Leggott.

I wrote some posts on my blog.

I went on a diet: I’ve lost 20 kilos so far.

Oh, and I did take the trouble to look up that story. It turns out that it isn’t five years he has to spend in the room, it’s fifteen. Not 1824 days, but 5472. Not 24, but 71 times what we’ve just been through.

No doubt we’ll soon be back to normal. It hasn’t been five years – let alone fifteen – but you can’t really call it nothing, either.

Jack Ross

I’m obsessed with boats, and lockdown proves this

In particular, my lockdown dreams prove this. But I haven’t been dreaming of luxe

sailboats with white sails in perfect sea on Insta or the Med, or those little dinghies

set against the wall at Herne Bay or pretty much any bay on the Waitematā. I’ve

been dreaming of the big tinny past-their-prime rusty, probably oily ferries like the

interislander, like the Palace. And I’ve been dreaming of making it to these ferries

just in time, or of not making it and watching from the wharf. In one dream, I

watched from hill-top Fira in Santorini as the night ferry cut the caldera, in another

I kept slipping on the deck because the sea was beam. My mum made it onto that

one as well. If I wake up feeling sick I put it down to sea-sickness, if I wake up with

one of my migraines, then I must have slipped against the concrete at the port.

One time I dreamt of a library instead. There were books in glass cabinets that waiters

had to open, and they gave out black coffee too, espresso, and spoke in Italian. I’m

not kidding, this library was in Wellington.

Vana Manasiadis

photo: Ian Wedde

The Tree Outside My Window

The old Chinaberry tree outside our

bedroom window stretches two stories up

across the footpath and the patio

at the front of our place and shakes its pink

profusions of dainty multi-clustered

flower heads against the early morning

glassy glint of dawn above the empty

barbershop across the road where cheerful

morning trims have not been happening these

past few months and where the radio has

been denied the company of passing

cars and the muffled time-warp thud of

Kevin Gilbert’s ‘The Tears of Audrey’ or

some-such but why do I remember that?

But now it’s the birds that wake with dawn and

can be heard above the silence of no

traffic and no barbershop radio

where they gather among the fresh spring leaves

and blossoms and big yellow bunches of

Chinaberry also known as Bread Tree

or Persian Lilac, Pride of India,

Cape Lilac or, to be botanical,

Melia azedarach — they gather

among the tree’s many names that seem to

silence the silence of the neglected

barbershop and fill it instead with their

optimistic singing about what should

be happening right now, don’t remember?

And when the morning scatter of last night’s

leftover rice out there on the roadside

has drawn its quick crowd of darty sparrows,

plodding pedantic pigeons, strategic

down-swooping minah birds and sometimes a

gorgeous gaudy couple of rosellas —

when they’re all good with cleansing beak-swipes on

convenient branches of the Bread Tree,

then we brew coffee and speculate on

what the Morning Report will have to say

while outside among the leafy branches

of the Persian Lilac the sparrows that

Donna tells me have sophisticated

and highly evolved individual

recognition capabilities are

talking up the day’s chances and setting

agendas and trajectories out of

the Pride of India towards options

elsewhere across the city where under

other Cape Lilacs fresh scatters of left-

over life-support are not left wanting.

Melia azedarach is a

Tree of Life as its many names tell us

and of worlds and many flocks of sparrows

with highly evolved individual

recognition capabilities as

noted above and so a multiverse

of diverse voices and of course of wing-

spans and what’s entailed thereby not least near

or far horizons and even gaudy

strangers whose songs and head-bobs are foreign

though the tree in which they show themselves is

where the familiar sparrows clean their beaks.

But then it’s evening and they’re back, the birds —

the sparrows without fail and the boring

(sorry) pigeons but now impertinent

black-and-white magpies when they so choose and

I see them defer or something like nod

to the sparrows whose ‘individual

recognition capabilities’ are

why they know when to wake us at the crack

of dawn and as the sun prepares to set,

like, how hard is this? Yes, Bread Tree, Persian

Lilac, Cape Lilac, Pride of India,

Chinaberry, tree of life and dawning,

Melia azedarach, we’re open

for whatever news comes like it or not.

Ian Wedde

Martian Wedding

Henry says his sister, the Queen of Mars, is getting married. Even though he is eight, he cackles at the news like an old man. His sister Marsha is 18, but teenaged brides are usual on Mars. We are in our silver hatchback crawling over the harbour bridge in the hot sun. Henry is an only child and now siblings punctuate his stories like satellites.

We hold the wedding in our backyard. I bake a chocolate cake with Henry in the afternoon. I buy sprinkles from the supermarket, and Henry decorates the cake with pink love hearts, and tiny, white and peach pearls, because it is a wedding cake. I wonder about gently instilling parental advice, about exploring life before marrying anyone.

We put on our winter jackets and go sit out on camping chairs, on the wooden platform before our small square of lawn in front of the neighbor’s. I light beeswax candles and we take out the cake, and L&P, and jelly dinosaurs that Henry decides he doesn’t like. It is dark. I play Space Oddity on my phone.

Henry is the M.C. and is going to make a welcome speech.

“I’ve never made a speech before,” he says.

“You’ll be great,” I tell him.

When Marsha arrives, she wears a red dress, to symbolize her home planet. She marries a Martian with bright orange skin and gold hair. The Moon rises down the side of the house, full and white. We eat cake. We dance to David Bowie singing, ‘Ís there life on Mars?’.

Even with one thousand Martian guests, I win a prize for being the best dancer.

Henry says, “Are we family?”. He means that his Dad and I are together, but not married. We have lived together for over a year; Henry lives with us every second week.

“Um, I think so”, I say, “I think of you and your Dad as my family.”

That night I dream of my past wedding. Me at 25, wearing a pink dress, with a chocolate wedding cake, and how my Dad was still alive. How certain I was. The pain wakes me, rising from the depths of my psyche.

How love causes us to face painful things, like the shine of impact glass on a red planet.

Tulia Thompson

You might think a children’s book author would find the longest sentence a difficult traverse. Instead, I float languidly, bathing in the still waters of time. Time barely moves – no distraction, no heavy pull of urgent tides to bring me back to shore. I have time to weigh words. Measure the weight – one against the other. Concrete or air. Or a question of syllables that fit to some sound. A sitar that strums in my ear.

Long sips of black coffee. Long walks through shadows of trees. Shoes wet from long grass.

Long nights, the train trudges past, its empty carriages are sighing, what is our purpose now?

The long distance of family and friends, no hugging, no touch makes words more meaningful. The longest conversations with: my son, who is now jobless, plants seeds in his rented backyard; a fellow student from a class I am taking – in one afternoon, I learn more about her than I have all year; my sister has a lung condition, she’s had it for years, she finds breathing difficult, this virus air can kill her, she’s stressed, I give the wrong advice when I say, take a long, deep breath; my mother repeats recipes, cumin, coriander, tumeric; a stranger who by conversation’s end is like a long-time friend. She has read a good book, she tells me the plot. It’s about a found journal, a long-lost lifestory rescued from a dumpster. I may never read the book, the tiny piece of story fills my mind and floats with me.

Vasanti Unka

28th October 2021

11:32 am

Feeling better today, took yesterday off work to let the second vaccine settle. Sore arm, headache and lethargy. My wonky type one diabetic immune system pounced on it. Serves me well for doing right. Back behind the desk today, “Contractor” letters coming in advising my team to be on site, double vaccine and negative PCR test before attending, becoming the norm.

Pen and Dan have popped out. I’ve put Mandolin Orange on the turntable and catching up on yesterday’s emails. This mahi has taken me away from poetry. Paula asked me to write to this kaupapa – so here it is, a break in routine. To sit and reflect, not narcissus I hope, but contemplation, ioe, looking back.

My grandmother Edwina was born during the “Spanish Lady” outbreak in Apia, no Jacinda led government to protect her, our Aiga, our beautiful people. Aotearoa is moving on from elimination, to a risk assessment of a ninety percent vaccinated cohort.

Our son Daniel has been away from his class for too long – we see it in his temperament, his sullen moments, he turned 9 on October 3rd. I was 9 in Tulaele with my Grandmother, translating her world, Dan is in lock down translating the future.

Pen and I are doing our best, she keeps me afloat on the days I want to drag myself ashore and beach. Life in the time of lock down was not the future I saw for us. Pen has made new pathways. She is navigator and artist. Pen is protecting our whanau; her paintbrushes are hammers!

I better get back to it, my manager is calling, breaking my reflection into a million pieces…

2:04 pm

I am waiting in the lobby of a Zoom meeting with a clinical engineering department of a DHB I shall not name. They are late!

Zoom, Teams, Skype – this is the stuff of science fiction from my childhood right, I mean Star Trek

Shit, it’s started…gotta go

2:57 pm

Interruptions and fractures, it is the new normal – “locked down” – stay on your toes, anything can happen!

Writing poetry in lock down is near impossible – I read Nick Cave related nobody wants to expose their families and partners to the horror of an artist at work – I agree!

That reminds me it’s Halloween on Sunday; my son Parone Vincent’s 23rd Birthday!

I’m tired, think I’ll end my working day early – all things going well – who knows if I’ll be interrupted?

Mauri Ola!

Doug Poole

Possession

She sits in front of me

Mouth agape, hands splayed

Eyes wide and flickering

A static zombie

The others are too

In our little boxes

we choreograph our techno egregores

I study her

The other voices float

beside me in broken chunks

as my binary code usurper

pixelates and shifts

Poised now, hands in her lap

She nods when I do and

plays the part of listening so well

Her smile is made from my teeth

My crow’s feet ripple when she pulls my face into her reactions

I observe as she takes over

She puppeteers me through the screen

She controls my flailing tongue

My thick thumbed twitter typos

Poses and preens my features in the front camera

I am just source material

Her virtual tendrils have captured me

and she knows that

object permanence is fleeting

If we cease to post, we cease to exist

We merge into the imaginary

dislocated and glitchy and sprawling

The gaps between my code are widening

Porous, endlessly scrolling

changing shapes and being sucked in

tapping on glass and yelling

Can you hear me?

The ultra-fibre bridge is crumbling

My rain fade is swelling

Are you there?

Bianca Rogers-Mott

The Open Sky Is In Your Mouth

exhale

inherited in my chest

I learn how to untrap it

ease it down to my stomach

and expand

church

is the open sky

in your mouth

where saliva is warm with mother’s breath

where memories are not riddled by illness

are always true, in the moment

land

as fetus mother

that cannot be contained

unbinding from inherited trauma

releasing generations

may we be like water

the flood that cooled the fever

that made the world hot and exposed its wounds

Grace Iwashita Taylor

Lockdown delivery

A feral cat ricochets through my house. A marmalade bullet

with frantic topaz eyes. Dives between the divan and southwest

bedroom wall. She’s queening. Hunkers. Self-soothes with purrs.

Pants.

Organza curtains swell. Lift embroidered leaves into winter’s

retreating bluster. Empty and fall. The cat trembles. Raises her

swollen belly.

Wails.

Little Cat. Little Cat. Little Cat! I’ll help you. Promise.

Little Cat hisses. Crawls into the shadowy recess between drawers.

Shrieks

and shrieks.

I record her travail. Contact the local vet. Press Play.

“Bring her in,” says reception. “Ring the clinic from your car upon arrival.

Make a contactless delivery. Lockdown rules. You can’t come in.”

It’s Level Four. I’m self-isolating. Complete questionnaires for Covid-19

contact tracers every morning. Can’t deliver wedged kittens to a vet. Can’t

receive visitors.

I’m not accustomed to delivering cats. Lie on the divan. Tentatively lower

an arm, an exploratory tentacle, into the hissing void.

… Retrieve what’s left of it.

Retreat.

One more negative swab, Little Cat. That’s all I need for a release call.

Little Cat squeals.

Delivers.

Serie Barford

microclimate

from the inside it doesn’t even seem like a storyline

another day’s luck piles up by the front door

at least i have a front door lukewarm comfort

brittling bones and news about britney

being the awkward dawn chorus guest when i know

i’m the species fucking this up

and i can’t work out how to stop

in la nina in my neighbourhood the water

reaches from dirt into deep space

with air you could drink, but never cool off in

every green thing on fire with new life

and dark lumps of clouds your mood models

tropical lowering a storm that can never

get it together enough to happen

the only thing dry is the lightning

and your matching set of accusations

cat claws from behind the curtains

just for hell of it letting the hell spill

out a bit on the kitchen floor in fluro pink

and then clean it up and trudge on through

this slow-mo crash of a day fever dreams

and zoom meeting makeup and waiting to rain

Stephanie Christie

I’m my favourite imaginary friend.

I wouldn’t tell everyone especially children – so exacting around grownups. My IF doesn’t have a name. I just call them IF or If for short. I use them/they for If partly because my non-IFs are mostly, she/her/hers/he/his/hims, and I can’t imagine these thems as anything but what they virtually are. One thing I’ll say about If: they’ve dubbed me ‘The I That Can’t Say No’. I can be rather maybe, I’ll get back to you, but before you can muddy me a martini, I’m at the bar or in the cinema, that place we used to go Pre-C, sit in the dark with many other people and escape into imaginary worlds. The real me has always been quite iffy.

I’m my favourite fairy tale.

Sometimes I’m the Big Bad Wolf in leathers on my big bad motorbike à la Tom of Finland huffing an’ puffing on a Bourbon Flava-Vape. Sometimes I’m Rapunzel with long blond hair which I won’t let down in case I’m let down when I let up. Cliches are the stuff of fairy telling. I’ve always had a soft spot for that princess with the pea although in the early a.m. this is more Grimm than gorgeous with paracetamol and a hottie for the lower back. I’m quite often Prince Charming. I wear shapely silver tights with crystal slippers and write sonnets on my dark youth. I’ve yet to kiss Sleeping Beauty or Cinderella. Sometimes I’m Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty, and Prince Charming (also I) hovering with pink lips puckered for the kiss of life, love, but not happily ever after. That’s one fairy tale too once upon a time far, far away for me.

I’m my favourite porn star.

I’m hardly well known, never had a huge online presence but if I did my porn name would be, apparently, PussPussPuss Westwood Terrace. Not quite West Hollywood, although when there in the mid-80s I do recall a certain popularity. They adored my Down Under accent. I spent a lot of time humming m m MM-mmm – HEY- m m m m-m M mmm. Madonna and I are both from large Italian Catholic families. So candid the Yankees. That time in the hot tub in San Fran when Drew drawled, “Micky, I find you very attractive. I just wanna know what you’re gonna do about it”. Still gives me a giggle.

Michael Giacon

Olivia Macassey ‘Testament‘ 2021.

Large format print, paper, wood (841 x 1200 mm). In A Pandemic Moment in Time, Oct 2021–Jan 2022, Quest Gallery, Whangārei, curated by Filani Macassey.

On Egretta sacra in descent

On the descent of Pacific reef herons

from a magnolia of night along their endless

curves of desire, its gossamer threads

The electric ocean charges / discharges as a wild north-eastern

sea collides in foam of argument over Mangawhai Heads

dune cliff harbour mouth rocky reef tidal current vector confluence

On the sheltered side, young pied shags in pōhutukawa roost

drop their bright white splashes onto Pseudopanax below

On the open coast side Taranga incises the wind

Te Whara headland lies long brooding distant

and the low shoulders of Marotere Islands huddle

these sanctuaries all blazing natural profusions

bird song streams off in visible swirls of braided chords

At the kinetic confluence

kite surfers dance on pulsing waves of air

on lookers in awe of the aerial acrobatics

The fine sands trap easily in our eyes bringing tears

so we turn, walk back, heads bowed in the maelstrom

Back at the holiday park

we arrange a meal in the camp cookhouse, simple pasta and vegetables

despite the mid-winter there are people here to chat with

locals who home-school their children in lockdown

In the wind there’s blood,

it shifts, sorts, sifts, re-sorts the flesh of the world

layers of surfaces buried beneath are opened up

torn, cut, into skin, in the forest of gone

fall flowers of light, ambitious clouds in torment

The peninsula post

For now all is quiet on the Waitangi front. Below Rakaumangamanga cascades of bays melt in the summer sun. From giant fig shade, varieties of human experience and ultra-violet exposure emerge and dissolve into shimmering heat on Oneroa/Long beach.

A trilogy titled Bay Belle, Waitere Blue and Happy Ferry cross and criss from Paihia to here and back and back again here to Kororāreka. The R Tucker Thompson, a gaff rigged schooner under full sail cruises out on another afternoon from the hell hole of the Pacific. Now it’s a goulash of tourist accents and barely gravid honeymooners holding hands, holding conversation, holding berry blossoms of ice creams from the devilishly devilish parlour.

A duo in kayaks paddles over to that quiet beach below those cliffs. Outside the Duke, still refreshing rascals and reprobates since 1827, we toast deliciously (again) on the late afternoon gravel beach splashing into it, in to the pale silvery green, looking across to Waitangi at 2021 (again).

Through spreaders of yacht masts, flag poles, ship yardarms and gull wings our bodies stretch out reptilian under the pōhutukawa grey. On another day (again) luckier than we care to imagine, we watch the water through the trees. The waves carry the full moon through the branches, a tuna glances up

Piet Nieuwland

No Worries

I’m not really here today –

only my worries remain

Mum and dad are fighting again

hotly contesting the latest news

there’s money in anger they say

but the worries are yours for free.

They don’t want the old normal gone

as if we’d achieved something great

the ones at the top always telling us so

even though the rest of us know

nothing ever really changes

cos the worries always remain.

Melinda Szymanik

lockdown

lockdown.

he raka iho.

hōhā.

how do we circumvent

such cloisture?

lockdown.

te raka iho.

tino hōhā.

when will we slip

such smother?

e kāore mātou e pīrangi

tēnei aukatinga

more like lock-up.

engari

e kāore hoki mātou e pīrangi

te huaketo.

ka mate mātou he aha koa.

locked away forever.

[e kāore mātou e pīrangi

tēnei aukatinga – we do not want this restriction]

[engari

e kāore hoki mātou e pīrangi

te huaketo – but nor do we want the virus]

[ka mate mātou he aha koa – we will die no matter what]

tahi kupu anake

i he ao ki nui ngā kaitōrangapūpōrangi

i he ao ki nui ngā tangata rawakore

i he ao whakamahana o te ao

ko tūmanako te kupu.

i he ao ki nui ngā pakanga

i he ao o whakakonuka me apo

i he ao ki te mate ā-moa o ngā kararehe

ko tūmanako te kupu.

ko tūmanako te kupu anake

ko tūmanako te kupu

ko tūmanako.

[only one word

in a world of many mad politicians

in a world of many destitute people

in a world of global warming

hope is the word.

in a world of many wars

in a world of corruption and greed

in a world of the extinction of animals

hope is the word.

hope is the only word

hope is the word

hope.]

Vaughan Rapatahana

Out, in

I breathe out, in.

The rose sky bends down to touch the glassy water as I walk my 10,000 steps. The thin fabric of my mask sucks in and out with my breath. In and out with the tide.

In lockdown, I am an astronaut, the term used for migrants who fly to a different country for work while their families stay put. Moving between Level 2 and 3 is an overseas border crossing.

I wear scrubs to look the part of an essential worker. In Wellsford, I use the toilet and the free wifi outside McDonald’s. Then on my passenger seat I line up the items I know I’ll be asked for at the checkpoint: hospital ID, letter from my manager, roster, photo ID, evidence of last Covid test.

When I am overseas, my father rings me: hello? hello? when are you coming back? I need lollies. Urgently.

I breathe out, in.

My father has dementia. The glassy tide, once so full and splashing with life, is receding and layer by layer he is being uncovered. Now parts of his childish self are easily visible: he can’t resist opening packet after packet of his favourite sweets, gorging himself until they’re gone. When that happens, he picks up the phone to order more from his daughters.

We took away his keys so he couldn’t drive. Once, frustrated I was away and wouldn’t be back for two days, he tried walking to the dairy himself for lollies. He was found by a neighbour 100 metres from our house, having tripped and fallen. He spent the day in hospital having a brain scan to make sure there was no bleeding.

An hour is a year for my father. But a minute is too long to remember that he’s already called me.

I breathe out, in.

My father’s tide is still full enough to reflect the life around him. In my kitchen, he stands without needing his stick, closely observing as we bustle through dinner preparations. By close, I mean he gets told off by my mother for getting in the way.

‘I just like to watch you making food,’ he tells her.

Later, after they’ve eaten and collected their hugs from the grandchildren and headed home, I get an email. ‘Hi, Dad here, dinner was very good tonight. I’ll enjoy the leftovers for lunch tomorrow. Thank you.’

The receding tide has uncovered politeness and humility. Now, he always calls or emails to say he appreciates what we did. He does it right away, minutes after we’ve dropped off food or medicines, as if knowing that the minutes will slip away if he doesn’t.

The minutes slip away for all of us: most of us just forget that they do. Breathe out, in.

The daylight is nearly gone as I complete my walk. On the bridge, lights flicker into being, helping walkers see the path.

Breathe out, in.

Renee Liang

Amber Esau is a Sā-māo-rish writer (Ngāpuhi / Manase) born and raised in Tāmaki Makaurau. She is a poet, storyteller, and amateur astrologer. Her work has been published both in print and online.

Bianca Rogers-Mott (she/her) is a pākeha writer based in Kirikiriroa, and though she has a BA in English Lit from the Univesity of Waikato, she finds it increasingly difficult to write bios about herself. She enjoys writing about the monstrous feminine and delights in upsetting the traditional feminine stereotypes written by old white men. You can find more of her work in Starling Mag, if you like.

Brecon Dobbie finds poetry to be her place of solace. She writes to make sense of things, often without meaning to. Some of her work has appeared in Minarets Journal, Starling, Love in the Time of COVID Chronicle and Poetry New Zealand Yearbook.

Doug Poole is of Samoan (Ulberg Aiga of Tula’ele, Apia, Upolo) and European descent and resides in Waitakere City, Auckland, New Zealand. His work has been published in numerous Pacific and international literary journals and anthologies, and he serves as editor and publisher of the online poetry journal blackmail press.

Grace Iwashita-Taylor, breathing bloodlines of Samoa, England and Japan. An artist of upu/words led her to the world of performing arts. Dedicated to carving, elevating and holding spaces for storytellers of Te Moana nui a Kiwa. Recipient of the CNZ Emerging Pacific Artist 2014 and the Auckland Mayoral Writers Grant 2016. Highlights include holding the visiting international writer in residence at the University of Hawaii 2018, Co-Founder of the first youth poetry slam in Aoteroa, Rising Voices (2011 – 2016) and the South Auckland Poets Collective and published collections Afakasi Speaks (2013) & Full Broken Bloom (2017) with ala press. Writer of MY OWN DARLING commissioned by Auckland Theatre Company (2015, 2017, 2019) and Curator of UPU (Auckland Arts Festival 2020 & Kia Mau Festival 2021). Currently working on next body of work WATER MEMORIES.

Ian Wedde lives in Auckland with his wife Donna Malane. His most recent books are a novel The Reed Warbler (VUP 2020) and a book of poems, The Little Ache – a German Notebook (VUP 2021).

Jack Ross’s latest book is The Oceanic Feeling (Salt & Greyboy Press, 2021). He recently retired from Massey University, where he’s been teaching writing for the past 25 years, in the hopes of getting time to do a bit more of it himself.

Joanna Ji, 24-year-old artist and music creator: I’ve found comfort in creating music/sounds that communicate feelings that are hard to put in words, using art/music as a refuge. Simone and I sometimes exchange work, and when she first sent me this beautiful poem my mind was instantly taken to this piano piece I had composed resting in my archives that I wanted to offer as I thought it would canvas perfectly with the mood and rhythm of her healing and comforting words. I immensely enjoy within my friendship with Simone the wonderful feeling when someone manages to put words to that seemingly un-wordable feeling that I typically express in music.

Karlo Mila is a New Zealand-born poet of Tongan and Pākehā descent with ancestral connections to Samoa. She is currently Programme Director of Mana Moana, Leadership New Zealand. Karlo received an MNZM in 2019 for services to the Pacific community and as a poet, received a Creative New Zealand Contemporary Pacific Artist Award in 2016, and was selected for a Creative New Zealand Fulbright Pacific Writer’s Residency in Hawaii in 2015. Goddess Muscle is Karlo’s third book of poetry. Her first, Dream Fish Floating, won NZSA Jessie Mackay Best First Book of Poetry Award at the Montana New Zealand Book Awards in 2006.

Maddie Ballard is a writer from Tāmaki Makaurau. By day, she works as the deputy editor of dish magazine, but she is always trying to get more poetry into her life. You can read more of her work at Starling, The Pantograph Punch, The Oxford Review of Books, or on her blog.

Melinda Szymanik is an award-winning writer of picture books, short stories and novels for children and young adults. She was the 2014 University of Otago, College of Education, Creative New Zealand, Children’s Writer in Residence, held the University of Otago Wallace Residency at the Pah Homestead in 2015, and was a judge for the 2016 NZCYA Book Awards.

Michael Giacon During these months of lockdown, poet Michael Giacon has found himself taking flights of the fanciful in a burgeoning series entitled either Playing Favourites or Avoidance Therapy. Plenty of time to decide.

Murray Edmond: b. Kirikiriroa 1949, lives in Glen Eden, Tāmaki-makau-rau. 15 books of poetry (Shaggy Magpie Songs, 2015, Back Before You Know, 2019 and, forthcoming, FARCE); book of novellas (Strait Men and Other Tales, 2015); Then It Was Now Again: Selected Critical Writing (2014); editor, Ka Mate Ka Ora; dramaturge for Indian Ink Theatre. Time to Make a Song and Dance: Cultural Revolt in Auckland in the 1960s was published by Atuanui Press, 2021.

Olivia Macassey’s poems have appeared in Poetry New Zealand, Takahē, Landfall, Brief, Otoliths, Rabbit and other places. She is the author of two collections of poetry, Love in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction and The Burnt Hotel (Titus). Her website.

Piet Nieuwland is a poet and visual artist who lives near Whangarei on the edge of the Kaipara catchment. His poetry and flash fiction has been published in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally in numerous print and online journals including Landfall, Atlanta Review, Sky Island Journal, Otoliths and Taj Mahal Review. This year, his book, As light into water was published by Cyberwit and Fast Fibres Poetry 8 has just been launched, co-edited with Olivia Macassey. He appears in Creative Conservation New Holland and Take Flight, a new anthology of Whangarei poets. An exhibition of his drawings, painting and poetry A look back to now was recently held at Hangar Gallery in Whangarei. website

Renee Liang is a poet, playwright and essayist. She has toured eight plays and collaborates on visual arts works, dance, film, opera, community events and music. Some poetry and short fiction are anthologised. A memoir of motherhood, When We Remember to Breathe, with Michele Powles, appeared in 2019. In 2018 she was appointed a Member of the NZ Order of Merit for services to the arts.

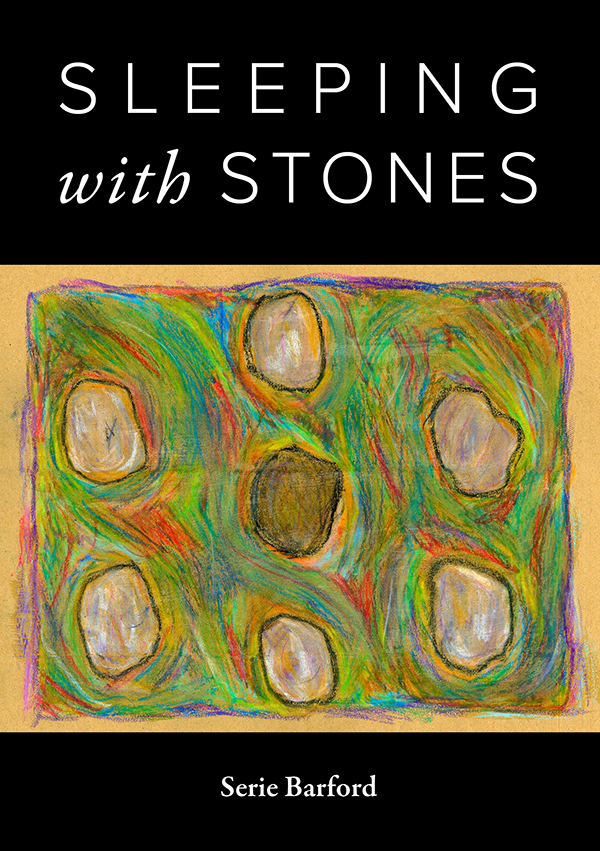

Serie Barford was born in Aotearoa to a German-Samoan mother and a Pālagi father, and grew up in West Auckland. She has published poems online and in journals, along with four previous collections. In 2011 she was awarded the Seresin Landfall Writer’s Residency and in 2018 the Pasifika Residency at the Michael King Writers’ Centre. Serie promoted her collections Tapa Talk and Entangled Islands at the 2019 International Arsenal Book Festival in Kiev. Sleeping With Stones was launched during Matariki, 2021.

Simone Kaho is the author of Lucky Punch, and is the 2021 IIML Emerging Pasifika Writer in Residence.

Stephanie Christie makes poetry in the form of page poems, text art, installations, theatre, video and sound works. She recently shared 3D poems in the Mesoverse and in the Kotahitanga project. She’s obsessed with how it feels to be an animal half-buried in language.

Tulia Thompson is of Fijian, Tongan and Pākehā descent. She has produced poetry, creative non-fiction and the children’s fantasy Josefa And The Vu; and an essay included in Life on Volcanoes – Contemporary Essays. She is working on a collection of personal essays.

Vana Manasiadis is back in Tāmaki Makaurau after her spell in Ōtautahi. She was 2021 Ursula Bethell Writer-in-Residence at Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha Canterbury University. Her most recent book was The Grief Almanac: A Sequel (Seraph Press).

Vasanti Unka is an award winning children’s book writer, designer and illustrator noted for the originality of her storytelling and her riotously colourful and inventive illustrations. In 2021 she won the Arts Foundation Mallinson Rendel Laureate Award for Illustration. Vasanti lives in suburban Auckland.

Vaughan Rapatahana (Te Ātiawa) commutes between homes in Hong Kong, Philippines, and Aotearoa New Zealand. He is widely published across several genres in both his main languages, te reo Māori and English, and his work has been translated into Bahasa Malaysia, Italian, French, Mandarin, Romanian, Spanish. Additionally, he has lived and worked for several years in the Republic of Nauru, PR China, Brunei Darussalam, and the Middle East. He has participated in several international festivals including Colombia’s Medellin Poetry Festival, The Poetry Interntaional Festival at London’s Southbank and World Poetry Recital Night, Kuala Lumper. Vaughan’s new poetry collection is entitled ināianei/now (Cyberwit).