| The $10,000 Peter Porter Poetry Prize is now open |

| Judged by Sarah Holland-Batt, Jaya Savige and Anders Villani |

| First Prize: AU$6,000Four other shortlisted poets: AU$1,000 eachClosing date: Midnight, 4 October 2021 Australian Book Review welcomes entries in the eighteenth Peter Porter Poetry Prize, one of Australia’s most lucrative and respected awards for poetry. Entries must be an original single-authored poem of not more than 70 lines written in English. The Porter Prize is worth a total of AU$10,000. It honours the life and work of the great Australian poet Peter Porter (1929–2010), an esteemed contributor to ABR for many years. The five shortlisted poems will be published in the January–February 2022 issue and the winner will be announced at a ceremony in January. |

| Click here to enter the 2022 Porter Prize |

| Entry costs Entry costs AU$15 for current ABR subscribers or AU$25 for non-subscribers*. Entrants who are not current ABR subscribers can choose to subscribe when submitting their poem for the special combined rates listed below: Entry + ABR digital one-year subscription – $80Entry + Print one-year subscription (Australia) – $100Entry + Print one-year subscription (NZ and Asia) – $190Entry + Print one-year subscription (Rest of World) – $210 *Non-subscribers will receive digital access to ABR free of charge for four months from entry. |

| Terms and Conditions / FAQs Before entering the Porter Prize, all entrants must read the Terms and Conditions. Before contacting us with a question, please read our Frequently Asked Questions. Click here for more information about past winners. |

| Please forward this information on to friends, colleagues and students who may be interested in hearing about the Porter Prize. ABR gratefully acknowledges the long-standing support of Morag Fraser AM and Andrew Taylor AM. |

Monthly Archives: July 2021

Poetry Shelf in the city: Breakfast with secondary-school English teachers

This morning I had breakfast and conversation with five fabulous secondary-school English teachers (Bronwyn, Susan, Terri, Tom and Christine) in Mt Eden and it was such a treat (here for the NZATE conference). I say no to pretty much everything at the moment, because I am focusing on my own writing, and keeping my two blogs going. It’s a rare occasion I get to have a cafe breakfast and talk poetry, and I just loved it! And yes poetry was the main topic of conversation. I gave each teacher a one-off offer to invite one standout young poet to send me a few poems – and I would write back to them, and perhaps post a poem on the blog. I tried starting an ongoing spot for secondary-school students awhile ago but it fizzled. But I love the idea of finding a way of posting poems by secondary-school students. Hmm. I need to muse on this.

I was talking off the cuff this morning but one thing I kept returning to was how we can take our whole body into a poem, whether we read or write it. Ears might come into play first because so often we pay attention to the sound of the poem. The way it makes music. Eyes are a way of hunting for the detail that moves a poem from the general to the specific. The look of the poem on the page. Its form. Its page space. Heart might be the essential pulse of a poem, the way we feel the world. And lungs, because poetry is also breath. Mind, because ideas can matter. Poem can be a form of inquiry, curiosity, experimentation. How does this all work when you are exploring a poem as a set of language features? You might think of a poem as a set of rhymes. Yes various sound rhymes, but also visual rhymes, feeling rhymes. Near rhymes, off rhymes. Ideas that rhyme. Recognition rhymes. A rhyme between you as reader or writer and the poem itself. I say rhyme but I could say chord or I could say connection. I often picture a bridge between myself and the poem, and sometimes I just can’t cross it. So I ask, why not? That instantly fascinates me, and I hunt for new entry points, a backdoor, a portal, a keyhole. Poetry for me is a way of opening up not closing down. Poetry, even at my age, is all about play, no matter how serious I get.

Afterwards, on my drive back to the coast, I mused on the ways poetry can spark students into finding their voice, into exposing diverse engagements with themselves and the world, with people, things, feelings, places, experiences and ideas that matter to them. I got to wondering to what degree our students read New Zealand fiction and poetry? I know there is an exciting groundswell of young poets from teens through to 20s. The work appearing on Starling underlines that. It seems so very important and is no doubt one reason we have Ben Brown as our inaugural Te Awhi Rito Reading Ambassador.

I got to read a poem from my New York Pocket Book (Seraph Press) that is so dear to me, the poetry prompted by the time Michael and our then teenage girls had ten nights in New York. Such an experience seems like a foreign country to us at the moment. And here I was today, reading a New York poem in a Mt Eden cafe to five English teachers, and it felt so unbelievably special I felt like crying. But I held up my latest collection The Track and got talking about creating a whole book in my head in a storm. Which is kinda how I feel now – writing and blogging in a storm to keep going. To keep one foot going after the next. To keep holding out the warmth and sustenance that poetry can offer.

Thank you NZATE for the breakfast invite. I am so grateful.

Poetry Shelf celebrates new books: A poem sampler from Ian Wedde’s The Little Ache — a German Notebook

The Little Ache — a German Notebook, Ian Wedde, Victoria University Press, 2021

From The Little Ache—a German notebook

2

Im Hochsummer besuchen die Bienen viele unterschiedliche Blüten

‘In high summer the bees seek many different flowers’

caught my eye on the jar of honey

in the organic shop around the corner

in Boxhagenerstrasse

but outside it was already getting dark

at 4.30 in the afternoon

and the warm bars were filling

with a buzz of patrons

dipping their lips

into fragrant brews

jostling each other in a kind of dance

I didn’t join

(I didn’t know how to

couldn’t ‘find my feet’)

but took home my jar of Buckweizenaroma

buckwheat/bookwise aroma

and sampled some on a slice

of Sonnenblumenbrot.

6

Von allem Leid, das diesen Bau erfüllt,

Ist unter Mauerwerk und Eisengittern

Ein hauchlebendig, ein geheimes Zittern.

‘From all the suffering that fills this building

there is under masonry and iron bars

a breath of life a secret tremor.’

In the Moabit Prison memorial

where Albrecht Haushofer’s words

incised in the back wall

already wear the weary patinas of time and weather

or more probably the perfunctory smears

of graffiti cleansing

I’m assailed by a nipping dog

whose owners apologise in terms I don’t quite understand

though the dog does

and retreats ahead of the half-hearted kick

I lack the words to say isn’t called for.

The horizon’s filled with gaunt cranes

resting from the work of tearing down or building up

the forgettable materiality of history

an exercise one might say

in removing that which was draughty

and replacing it with that which can be sealed.

Or as it may be

tearing down the sealed panopticon

but making space to train dogs in.

21

Oberbaumbrücke

is one of those contrapuntal German nouns

that should be simple but isn’t

unless you think

‘upper-tree-bridge’ is simple.

The long trailing tresses of the willows

have turned pale green

and are thrashing in the wind

on the Kreutzberg side

of die Oberbaumbrücke

over the storm-churned Spree.

They are the uneasy ghosts of spring.

Gritty gusts

blow rubbish along the embankment.

In a crappy nook

a graffitied child clenches a raised fist.

Yesterday at the Leipzig Book Fair

I listened to a fierce debate

about the situation in Ukraine

and later visited the Nikolaikirche

where Johann Sebastian Bach had played the organ.

One situation was loud with discord

the other’s efflatus a ghostly counterpoint.

On the train back to Berlin

I received a text from Donna

who’d been rocking our granddaughter Cara to sleep.

My bag from the Book Fair

had a paradoxical misquote from Ezra Pound on it:

‘Literatur ist Neues,

das neu bleibt.’

The train was speeding at 200 kilometres an hour

towards the place I’m calling home

because it’s haunted by ancestors who left slowly

but surely

thereby established the first term

of my contrapuntal neologism:

Endeanfang.

26

The vanity of art

(Milan Kundera) –

In spring

I return to the Moabit Prison Memorial

Haushofer’s words are still there

writ large on the back wall

they seem a little faded

but that could be the effect

of lucid sunshine

which elongates the speeding shadows

of dogs chasing Frisbees

and picks out

the filigreed patterns of trees

beginning to be crowned

with pale baldachins of leaves.

The girl panhandling on the footpath

at Warschauer Strasse station

has scrawled an unambiguous request

on the cardboard placard

her dog’s sleeping head

seems to be dreaming:

‘cash for beer and weed

and food for the dog’.

What the ghosts of Moabit are saying

I find harder to understand.

The memorial park’s stark absences

move me

and the minimal architectural features

seem respectful and not vaunting.

But the silence here

which the happy dogs

vociferous nesting birds

industriously rebuilding cranes

and agitated railway station

do not fill

that silence

crowds into a place in the mind

that scepticism can’t reach

where ghosts gather obliviously

without caring if I sense them

or if any of this exists.

27

Patriotismus, Nationalismus, Kosmopolitismus, Dekadenz

are the words repeated over and over

by the artist Hanne Darboven

whose great work in the Hamburger Bahnhof

museum of contemporary art

like the nearby Moabit Prison Memorial

reduces what she knew

to the minimal utterances

the obsessive reductions

the repetitions

that anticipate the ghosts of themselves

in the silence of the archive.

Ian Wedde

Ian Wedde was born in 1946. He has published sixteen collections of poetry, most recently Selected Poems (2017). He was New Zealand’s Poet Laureate in 2011 and shared the New Zealand Book Award for poetry in 1978. The Little Ache — a German Notebook was begun while he had the Creative New Zealand Berlin Writer’s Residency 2013/2014 and often notes research done during that time, especially into his German great-grandmother Maria Josephine Catharina née Reepen who became the ghost that haunts the story of the character Josephina in Wedde’s novel The Reed Warbler.

Victoria University page

Poetry Shelf noticeboard: IIML students encounter Mīharo |Panoramic view of the Aratiatia Rapids at the National Library

from ‘Panoramic view of the Aratiatia Rapids’ by Jiaqiao Liu. The first in a series of nine responses to the Mīharo Wonder exhibition.

“While Mīharo Wonder is moored to the walls and arrested in its cases, its imaginative scope ranges freely – here is the best possible evidence of that.” — Peter Ireland, Mīharo Wonder co-curator

Writers encounter Mīharo Wonder

Wonder is a place where writing often begins — and each year, during the first six weeks of the MA in Creative Writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters, we set exercises designed to unlock the kind of wondering unique to each writer. In April 2021 we brought the MA students to the Mīharo exhibition in the hope that some of the resonant objects, images and artefacts might prompt stories, poems or essays. We gave them no brief other than to choose an exhibit and pursue the lines of imagination it prompted.

For these writers, encounters with the past have become acts of invention as well as recovery and re-evaluation. The exhibition becomes an observatory in which old stories give birth to new, the past is encountered with fresh eyes and transformed through the lens of the present. The writing presented here is only a sample of the work produced, and we imagine work by other writers will come to fruition in future. We’re grateful to National Library staff Peter Ireland, Anthony Tedeschi and Fiona Oliver for providing additional insight and background to the exhibition and to Mary Hay and Jay Buzenberg for publishing the student’s work on the website. And we hope you enjoy the wondering Mīharo has produced.

Chris Price, Tina Makereti and Kate Duignan

First response by here. They will continue each week.

Visit Mīharo Wonder in the gallery and online

Visit Mīharo Wonder at the National Library in Wellington

Experience the Mīharo Wonder online exhibition

Read the Encountering Mīharo blog series

Read the Mīharo Wonder blogs

Poetry Shelf noticeboard: Paula Green reviews Bryan Walpert’s Brass Band to Follow at Kete Books

Brass Band to Follow, Bryan Walpert, Otago University Press, 2021

Bryan Walpert, professor of creative writing at Massey University, has published three previous poetry collections. His fourth, Brass Band to Follow, is a rewarding read with distinctive tones and exquisite layers. The book’s opening quotes suggest we are entering poetic engagements with middle age. Yes, age is a visible concern but the poems are alive with movement that includes but stretches beyond time passing.

The book is thoughtfully structured: you move in and out of dense single-verse poems along with airy multi-versed examples. A rocky outcrop on one page, thistle kisses on the next. It is like listening to music that favours both solo violin and the greater orchestra.

Full review here

Bryan reads poems on Poetry Shelf

Otago University Press page

Bryan Walpert website

Bryan in conversation with Lynn Freeman Radio NZ National

Poetry Shelf Monday poem: Cilla McQueen’s ‘Festival Time’

Festival Time

Pearl-grey moiré silk

above a base-line of pewter,

high top notes cloudy gold.

Oyster Festival tomorrow,

the day the road is jammed with traffic,

the day Bluff is invaded by lovers;

thousands of salt-sweet mouthfuls

dredged from their seabed, shucked deftly,

swallowed alive by the roistering crowd.

Too many people – I’m staying home.

After this rain the paradise ducks will come

down to the green field patched with sky.

Cilla McQueen

Cilla McQueen lives and writes in the southern port of Bluff. A recipient

of multiple awards for her poetry, she eats oysters as often as possible. Cilla’s most recent works are In a Slant Light: a poet’s memoir (2016) and Poeta: selected and new poems (2018), both from Otago University Press.

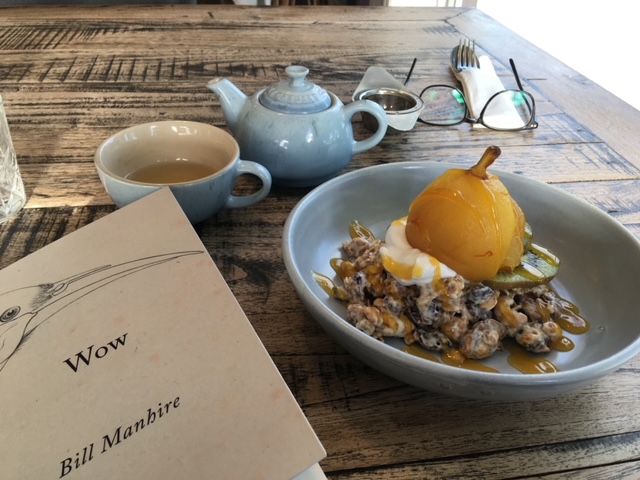

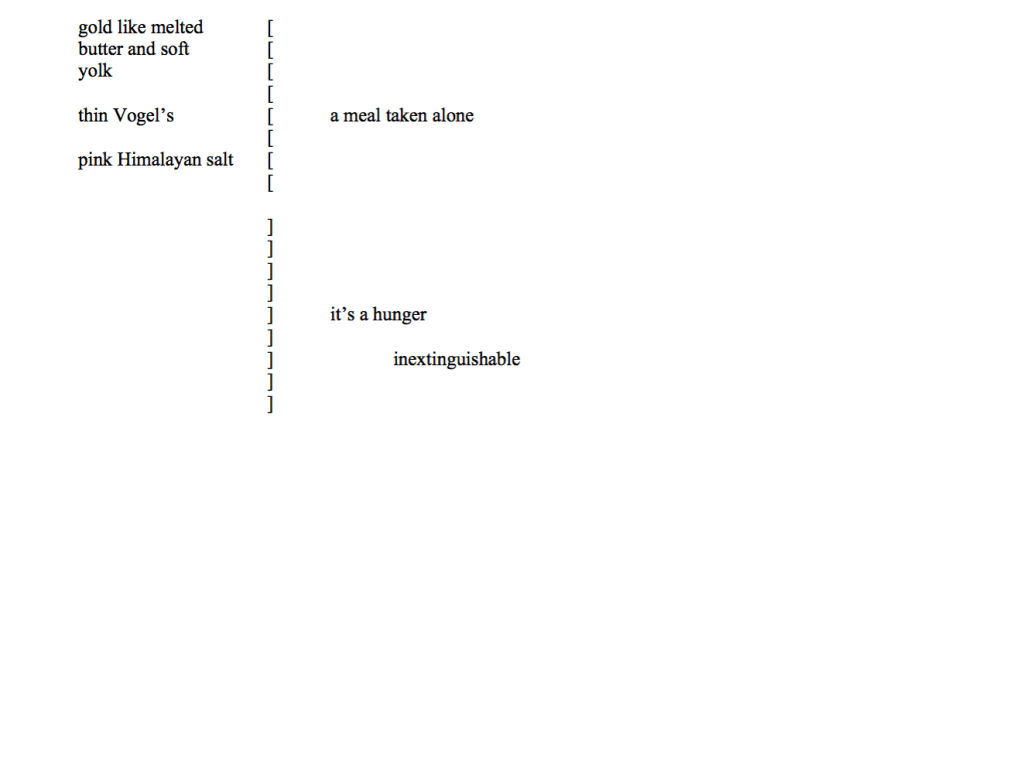

Poetry Shelf Theme Season: Eleven poems about breakfast

Breakfast is a lifelong ritual for me: the fruit, the cereal, the toast, the slowly-brewed tea, the short black. It is the reading, it is the silence, it is the companionship. It is finding the best breakfast when you are away at festivals or on tour, on holiday. This photograph was taken last year at Little Poms in Christchurch when I was at WORD. One of my favourite breakfast destinations. Breakfast is my gateway into the day ahead, it is food but it is more than food. It is the ideas simmering, the map unfolding, the poem making itself felt.

The poems I have selected are not so much about breakfast but have a breakfast presence that leads in multiple directions. Once again I am grateful to publishers and poets who are supporting my season of themes.

Unspoken, at breakfast

I dreamed last night that you were not you

but much younger, as young as our daughter

tuning out your instructions, her eyes not

looking at a thing around her, a fragrance

surrounding her probably from her

freshly washed hair, though

I like to think it is her dreams

still surrounding her

from her sleep. In my sleep last night

I dreamed you were much younger,

and I was younger too and had all the power –

I could say anything but needed to say

nothing, and you, lovely like our daughter,

worried you might be talking too much

about yourself. I stopped you

in my arms, pressed my face

up close to yours, whispered into

your ear, your curls

around my mouth, that you were

my favourite topic. That

was my dream, and that is still

my dream, that you were my favourite topic –

but in my dream you were

much younger, and you were not you.

Anna Jackson

from Pasture and Flock: New & Selected Poems, Auckland University Press, 2018

By Sunday

You refused the grapefruit

I carefully prepared

Serrated knife is best

less tearing, less waste

To sever the flesh from the sinew

the chambers where God grew this fruit

the home of the sun, that is

A delicate shimmer of sugar

and perfect grapefruit sized bowl

and you said, no, God, no

I deflated a little

and was surprised by that

What do we do when we serve?

Offer little things

as stand-ins for ourselves

All of us here

women standing to attention

knives and love in our hands

Therese Lloyd

From The Facts, Victoria University Press, 2018

How time walks

I woke up and smelled the sun mummy

my son

a pattern of paradise

casting shadows before breakfast

he’s fascinated by mini beasts

how black widows transport time

a red hourglass

under their bellies

how centipedes and worms

curl at prodding fingers

he’s ice fair

almost translucent

sometimes when he sleeps

I lock the windows

to secure him in this world

Serie Barford

from Entangled islands, Anahera Press, 2015

Woman at Breakfast

June 5, 2015

This yellow orange egg

full of goodness and

instructions.

Round end of the knife

against the yolk, the joy

which can only be known

as a kind of relief

for disappointed hopes and poached eggs

go hand in hand.

Clouds puff past the window

it takes a while to realise

they’re home made

our house is powered by steam

like the ferry that waits

by the rain-soaked wharf

I think I see the young Katherine Mansfield

boarding with her grandmother

with her duck-handled umbrella.

I am surprised to find

I am someone who cares

for the bygone days of the harbour.

The very best bread

is mostly holes

networks, archways and chambers

as most of us is empty space

around which our elements move

in their microscopic orbits.

Accepting all the sacrifices of the meal

the unmade feathers and the wild yeast

I think of you. Happy birthday.

Kate Camp

from The Internet of Things, Victoria University Press, 2017

How to live through this

We will make sure we get a good night’s sleep. We will eat a decent breakfast, probably involving eggs and bacon. We will make sure we drink enough water. We will go for a walk, preferably in the sunshine. We will gently inhale lungsful of air. We will try to not gulp in the lungsful of air. We will go to the sea. We will watch the waves. We will phone our mothers. We will phone our fathers. We will phone our friends. We will sit on the couch with our friends. We will hold hands with our friends while sitting on the couch. We will cry on the couch with our friends. We will watch movies without tension – comedies or concert movies – on the couch with our friends while holding hands and crying. We will think about running away and hiding. We will think about fighting, both metaphorically and actually. We will consider bricks. We will buy a sturdy padlock. We will lock the gate with the sturdy padlock, even though the gate isn’t really high enough. We will lock our doors. We will screen our calls. We will unlist our phone numbers. We will wait. We will make appointments with our doctors. We will make sure to eat our vegetables. We will read comforting books before bedtime. We will make sure our sheets are clean. We will make sure our room is aired. We will make plans. We will talk around it and talk through it and talk it out. We will try to be grateful. We will be grateful. We will make sure we get a good night’s sleep.

Helen Rickerby

from How to Live, Auckland University Press, 2019

Morning song

Your high bed held you like royalty.

I reached up and stroked your hair, you looked at me blearily,

forgetting for a moment to be angry.

By breakfast you’d remembered how we were all cruel

and the starry jacket I brought you was wrong.

Every room is painted the spectacular colour of your yelling.

I try and think of you as a puzzle

whose fat wooden pieces are every morning changed

and you must build again the irreproachable sun,

the sky, the glittering route of your day. How tired you are

and magnanimous. You tell me yes

you’d like new curtains because the old ones make you feel glim.

And those people can’t have been joking, because they seemed very solemn.

And what if I forget to sign you up for bike club.

The ways you’d break. The dizzy worlds wheeling on without you.

Maria McMillan

from The Ski Flier, Victoria University Press, 2017

14 August 2016

The day begins

early, fast broken

with paracetamol

ibuprofen, oxycodone,

a jug of iced water

too heavy to lift.

I want the toast and tea

a friend was given, but

it doesn’t come, so resort

to Apricot Delights

intended to sustain me

during yesterday’s labour.

Naked with a wad of something

wet between my legs, a token

gown draped across my stomach

and our son on my chest,

I admire him foraging

for sustenance and share

his brilliant hunger.

Kicking strong frog legs,

snuffling, maw wide and blunt,

nose swiping from side

to side, he senses the right

place to anchor himself and drives

forward with all the power

a minutes-old neck can possess,

as if the nipple and aureole were prey

about to escape, he catches his first

meal; the trap of his mouth closes,

sucks and we are both sated.

Amy Brown

from Neon Daze, Victoria University Press, 2019

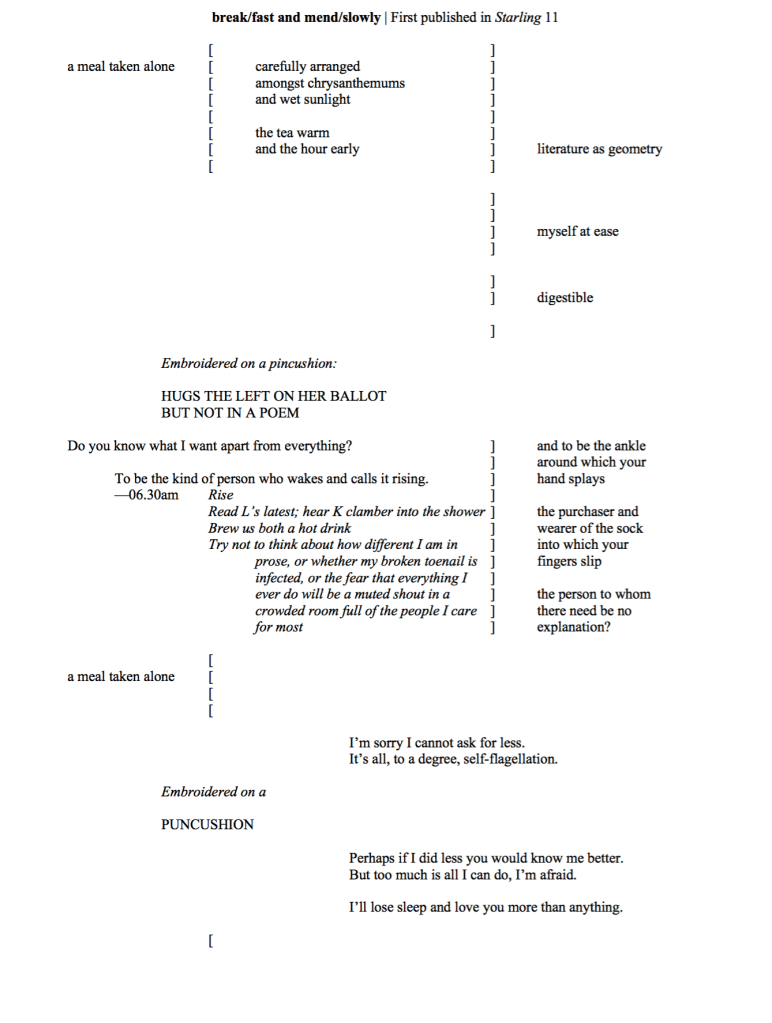

break/fast and mend/slowly

Tate Fountain

from Starling 11

I lay in our bed all morning

next to the half-glass of juice you brought me

to sweeten your leaving

ochre sediments settled in the liquid

a thin dusty film formed on the meniscus

but eventually I drank it

siphoning pulp through my teeth

like a baleen whale sifting krill from brine

for months after your departure I refused to look

at the moon

where it loomed in the sky outside

just some huge rude dinner plate you left unwashed

now ascendant

brilliant with bioluminescent mould

how dare you rhapsodize my loneliness into orbit

I laughed

enraged

to the thought of us

halfway across the planet staring up

at some self-same moon & pining for each other

but now I long for a fixed point between us

because from here

even the moon is different

a broken bowl

unlatched from its usual arc & butchered

by grievous rainbows

celestial ceramic irreparably splintered

as though thrown there

and all you have left me with is

this gift of white phosphorous

dissolving the body I knew you in

beyond apology

to lunar dust

Rebecca Hawkes

in New Poets 5, Auckland University Press, 2019, picked by Aimee-Jane Anderson-O’Connor

everything changing

I never meant to want you.

But somewhere

between

the laughter and the toast

the talking and the muffins

somewhere in our Tuesday mornings

together

I started falling for you.

Now I can’t go back

and I’m not sure if I want to.

Paula Harris

from woman, phenomenally

Breakfast in Shanghai

for a morning of coldest smog

A cup of black pǔ’ěr tea in my bedroom & two bāozi from the

lady at the bāozi shop who has red cheeks. I take off my gloves,

unpeel the square of thin paper from the bun’s round bottom.

I burn my fingers in the steam and breathe in.

for the morning after a downpour

Layers of silken tofu float in the shape of a lotus slowly

opening under swirls of soy sauce. Each mouthful of doufu

huā, literally tofu flower, slips down in one swallow. The

texture reminds me of last night’s rain: how it came down

fast and washed the city clean.

for homesickness

On the table, matching tiny blue ceramic pots of chilli oil,

vinegar and soy sauce. In front of me, the only thing that

warms: a plate of shuǐjiǎo filled with ginger, pork and cabbage.

I dip once in vinegar, twice in soy sauce and eat while the

woman rolls pieces of dough into small white moons that fit

inside her palm.

for a pink morning in late spring

I pierce skin with my knife and pull, splitting the fruit open.

I am addicted to the soft ripping sound of pink pomelo flesh

pulling away from its skin. I sit by the window and suck on the

rinds, then I cut into a fresh zongzi with scissors, opening the

lotus leaves to get at the sticky rice inside. Bright skins and leaves

sucked clean, my hands smelling tea-sweet. Something inside

me uncurling. A hunger that won’t go away.

NIna Mingya Powles

from Magnolia 木蘭, Seraph Press, 20020

Serie Barford was born in Aotearoa to a German-Samoan mother and a Palagi father. She was the recipient of a 2018 Pasifika Residency at the Michael King Writers’ Centre. Serie promoted her collections Tapa Talk and Entangled Islands at the 2019 International Arsenal Book Festival in Kiev. She collaborated with filmmaker Anna Marbrook to produce a short film, Te Ara Kanohi, for Going West 2021. Her latest poetry collection, Sleeping With Stones, will be launched during Matariki 2021.

Amy Brown is a writer and teacher from Hawkes Bay. She has taught Creative Writing at the University of Melbourne (where she gained her PhD), and Literature and Philosophy at the Mac.Robertson Girls’ High School. She has also published a series of four children’s novels, and three poetry collections. Her latest book, Neon Daze, a verse journal of early motherhood, was included in The Saturday Paper‘s Best Books of 2019. She is currently taking leave from teaching to write a novel.

Kate Camp’s most recent book is How to Be Happy Though Human: New and Selected Poems published by VUP in New Zealand, and House of Anansi Press in Canada.

Tate Fountain is a writer, performer, and academic based in Tāmaki Makaurau. She has recently been published in Stuff, Starling, and the Agenda, and her short fiction was highly commended in the Sunday Star-Times Short Story Competition (2020).

Paula Harris lives in Palmerston North, where she writes and sleeps in a lot, because that’s what depression makes you do. She won the 2018 Janet B. McCabe Poetry Prize and the 2017 Lilian Ida Smith Award. Her writing has been published in various journals, including The Sun, Hobart, Passages North, New Ohio Review and Aotearotica. She is extremely fond of dark chocolate, shoes and hoarding fabric. website: http://www.paulaharris.co.nz | Twitter: @paulaoffkilter | Instagram: @paulaharris_poet | Facebook: @paulaharrispoet

Rebecca Hawkes works, writes, and walks around in Wellington. This poem features some breakfast but mostly her wife (the moon), and was inspired by Alex Garland’s film adaptation of Jeff Vandermeer’s novel Annihilation. You can find it, among others, in her chapbook-length collection Softcore coldsores in AUP New Poets 5. Rebecca is a co-editor for Sweet Mammalian and a forthcoming collection of poetry on climate change, prances about with the Show Ponies, and otherwise maintains a vanity shrine at rebeccahawkesart.com

Anna Jackson lectures at Te Herenga Waka/Victoria University of Wellington, lives in Island Bay, edits AUP New Poets and has published seven collections of poetry, most recently Pasture and Flock: New and Selected Poems (AUP 2018).

Therese Lloyd is the author of two full-length poetry collections, Other Animals (VUP, 2013) and The Facts (VUP, 2018). In 2017 she completed a doctorate at Victoria University focusing on ekphrasis – poetry about or inspired by visual art. In 2018 she was the University of Waikato Writer in Residence and more recently she has been working (slowly) on an anthology of ekphrastic poetry in Aotearoa New Zealand, with funding by CNZ.

Maria McMillan is a poet who lives on the Kāpit Coast, originally from Ōtautahi, with mostly Scottish and English ancestors who settled in and around Ōtepoti and Murihiku. Her books are The Rope Walk (Seraph Press), Tree Space and The Ski Flier (both VUP) ‘Morning song‘ takes its title from Plath.

Nina Mingya Powles is a poet and zinemaker from Wellington, currently living in London. She is the author of Magnolia 木蘭, a finalist in the Ockham Book Awards, a food memoir, Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai, and several poetry chapbooks and zines. Her debut essay collection, Small Bodies of Water, will be published in September 2021.

Helen Rickerby lives in a cliff-top tower in Aro Valley. She’s the author of four collections of poetry, most recently How to Live (Auckland University Press, 2019), which won the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the 2020 Ockham Book Awards. Since 2004 she has single-handedly run boutique publishing company Seraph Press, which mostly publishes poetry.

Poetry Shelf noticeboard: Meteor Literary Salon returns for a stellar Matariki

The iconic Meteor Literary Salon returns for a stellar Matariki at the Meteor!

A special Matariki focused salon will see four leading New Zealand poets dynamically performing their work!

The poets in question? Literary legends…

Hinewirangi Kohu-Morgan, artist, poet, and visionary, known as an important harbinger of Māori poetry written in English.

Te Kahu Rolleston, Ngaiterangi born writer, activist, battle rap artist, actor, scholar, educator, poet, and national spoken word champion!

Vaughan Rapatahana, poet, and author, known for often delivering his poems with a kōauau soundtrack backgrounding his words and having his works published in both his main tongues – te reo Māori and te reo Ingarihi.

David Eggleton, Aotearoa’s Poet Laureate, and recipient of the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Poetry!

Don’t miss your chance to see these four poets travel beyond standing still in an emphatic oral delivery of their work. Vaughan Rapatahana will be our MC and there will be some of our artists work available for sale at the event.

July 22, 7pm. Tickets $10 General Admission (including a glass and nibbles).

Poetry Shelf review: Iona Winter’s gaps in the light

gaps in the light, Iona Winter, Ad Hoc Fiction, 2021

‘Gaps in the Light uses form in innovative ways to express deeply the experience of loss and joy in ways I can’t remember reading anywhere else. Nothing is binary here – everything feels multidimensional, so perfectly complicated, like echoes off multiple surfaces. It’s simply astounding!’

Pip Adam, author of Nothing to See, The New Animals, I’m Working on a Building, and Everything We Hoped For

Iona Winter, Waitaha/Kāi Tahu, lives on the East Otago Coast. She holds a Masters in Creative Writing and has published two previous collections, Te Hau Kaika (2019) and then the wind came (2018). Iona’s latest work gaps in the light comes with ‘advance praise’, tributes from other writers that include Helen Lehndorf, Kirstie McKinnon and Pip Adam. I so loved this suite of endorsements I have shared an extract from Pip Adam’s comments above. If I had read these words browsing in a bookshop, I would have bought the book, resisted all chores and distractions, and started reading. I too adore this book , and like Pip, know of no other quite like it. The slow-building embrace of loss and joy sets up long-term residency as you read.

The collection is dedicated to Iona’s son Reuben (20.5.1994 – 17.9.2020), and the dedication page becomes a pause a prayer a bouquet of sadness before you turn the page. I stalled here. I waited at this border between life and death. And then I entered a peopled glade: characters voices circumstances. Iona lays her own pain and loss beneath the surface of every scene, the hybrid writing stretching delving recovering above the subterranean ache. Writing becomes preservation, connection, ebb and flow, fighting against and fighting for. It is writing as lament and it is writing as meditation.

I dwell on the phrase ‘Streams of consciousness like gaps in the light’. What does it mean, but more importantly what does it feel? The writing is leaning in and listening to the dark without letting go of the framing light. A little like the mother and daughter in ‘Swallows’:

When we go walking, I tell our daughter what it means when the raupō are bent and spiders have crafted cocoons — white flags signalling peace. We inhale autumnal pine needle paths that smell of Christmas too early.

Little deceptions we tell one another make the intolerable less so.

When on the beach a heart stone is picked up, just one from the cluster, to hold and to carry. The sentence is smooth like the heart stone, but a few lines later the sound shifts and hits your ear sharply: ‘When mildew and salt scratched at my insides, and my back hit the stippled deck — life met decay once again.’ You will move from terminal illness to birdsong, from what you do to keep going to what you see out the window. There is a muscular thread of grandmother and grandfather wisdom. There is the way you get thrown off balance, expectedly, unexpectedly. The recurring thoughts of a loved one, the sight of the moon that startles: ‘it throws me off balance / that look of yours / an unexpected full moon in daylight showing herself on the horizon’ (from ‘Whorls’).

Iona is translating personal experience into hybrid writing and it is incredibly potent. I can’t imagine how hard this book was to write, but it is a gift, a glorious taonga, a gift of aroha. Thank you, Iona, thank you.

I prefer to expose the greying strands of my hair.

I prefer kōrero in person as opposed to communicating

via the Internet.

I prefer to sing aloud in the car.

I don’t prefer silent unspoken things.

I prefer non-martyred compromise.

I prefer to tend my wounds before creating them for

another.

I prefer compassion to witch-hunts.

I prefer to believe in the possibility of something

beautiful, rather than fear the inevitable pain of loss.

I prefer to choose aroha.

from ‘Natives’

Ad Hoc page

Iona Winter page

Poetry Shelf: Iona reads ‘Gregorian’