A mini poetry reading for World Poetry Day, featuring poems by Oscar Upperton, Danez Smith and Chris Stewart, and one of Chris Tse’snown new poems.

Each month I pose a question to a handful of poets but the question I had for today just didn’t feel right so I invited a gathering (fleet, raft, bazaar, blessing, bouquet, brood) of poets to pick a poetry book that gives them solace.

Writing and reading give me solace as does planting vegetables (I recommend you plant a truck load of microgreens in these strange times) and doing my blogs. Baking bread. Walking on the beach just as the sun comes up. Cooking meals.

I have been thinking even when poetry challenges, tears away at my heart, I still find poetry a comfort. So many of the women in Wild Honey have given me solace, have kept me going through tough challenges. But I am going to pick Bill Manhire’s Lifted. It is a book that lifts you off the ground and then gently places you back again and you feel all the better for it. I feel the same way about the shimmery effects of Ian Wedde’s The Commonplace Odes. To these add I add Helen Rickerby’s extraordinary How to Live, a collection that draws women to the light so astutely, so beautifully, along with Anna Jackson’s exquisite I, Clodia, Tusiata Avia’s heart-smashing Fale Aitu: Spirit House, Jenny Bornoldt’s sublime The Rocky Shore, Nina Mingya Powles’s luminous Luminescent and Manon Revuelta’s heavenly girl teeth. These are a few of the books I return to.

To celebrate this special poetry gathering I will give away a copy of Jenny Bornholdt’s delicious Short Poems of New Zealand (VUP, 2018). Comment on the blog or FB or Twitter post with your choice of a poetry book that offers you solace.

Thank you for contributing, thank you for reading, thank you for sharing. Please nag me if i haven’t replied to an email or tell me if I have errors on a post. It is hard not to feel a little unsettled, the strange mood in the supermarkets clings, the need to keep in touch with news, with friends and family, the need to be diverted elsewhere.

At my Wellington festival session I said that aroha is glue of the poetry. We are still in this room together, connected through our love of poetry.

Kia kaha

Paula

A poetry gathering for solace

Johanna Aitchison

I would recommend The New Transgender Blockbusters by Oscar Upperton VUP, which has just been published by Victoria University Press, and contains poems that are gorgeous, uplifting, melancholic, and, most importantly, finely made. Oscar is a millennial poet who is old-fashioned in his craft sensibilities, in that he uses received forms frequently and freshly, and often rhymes. In times of chaos and uncertainty there is pleasure to found in the well-made thing.

Jenny Bornholdt

My poetry as solace book is:

Woods etc. by Alice Oswald, Faber and Faber 2005

Woods etc. because of the attention Oswald pays to nature. She’s so specific in her noticing. She looks and looks again and what she sees is extraordinary. She draws us into this experience of deep looking and her attentiveness is consuming and soothing.

Amy Brown

I’ve chosen Of Mutability, by Jo Shapcott (2010), which a friend gave me last Christmas, when we thought the changes were confined to school (he was leaving to teach elsewhere), and then to the climate (the country was suddenly on fire, the cities smoked). The title really refers to Shapcott’s body as it underwent chemotherapy, but it could apply to world at large right now. I especially like these lines from ‘Myself Photographed’:

Perhaps I always look like this.

Perhaps it is an expression of surprise

that I am in the world at all…

Ben Brown

William Blake: Selected Poems, Penguin Classics edition

I’ve loved the work of William Blake since I was a boy listening to my father quote him in the paddock as we walked the fence line: ‘To see a world in a grain of sand…’

A bit old school, but if I want to be somewhere else for a while, Blake does it for me.

Lynn Davidson

I have chosen a book that I read for solace: Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic, published by Graywolf Press and Faber & Faber in 2019.

This might seem a strange book to read for solace, but these days I want a book that can look at darkness and at light. Kaminsky is such a great writer, it’s a joy to read him. Deaf Republic can hold violence, rage, loss, love, romance and hope together in the same poem. That’s as solace-y as it gets for me these days!

Michelle Elvy

I think poetry is a form of solace because it reaches across all boundaries and connects us. In words, in ideas, in sound. Poetry is music. Poetry is heart and mind. Each night I read before I sleep – this month it has been Helen Rickerby, Anne Kennedy and Emma Neale. James Dickey’s poems (called ‘willfully eccentric’ and ‘naturally musical’) stay on my bedside table, always – a personal connection to my past, and solace in many ways.

I choose to share Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic (Graywolf Press, 2019) because it is remarkable in the way it takes on terror and at the same time invites community. It crosses boundaries between reality and dream, between language, gesture and feeling; it is specific and universal; it carries an obvious weight, but also a light and even humour. It is wholly human in all its complexities. It is angry, provocative, probing. It is a plea to pay attention – in a way that poetry can do, sometimes, better than anything else.

And it is also a joy – magical in its language, passionate in its message, boundless for the love conveyed in its pages.

Poetry as a form of solace? Oh yes.

Excerpts from Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic can be found in The New Yorker.

Watch the poet read Deaf Republic at the Woodberry Poetry Room, Harvard University, with an introduction by Fanny Howe (Kaminsky begins at approx. 7.48, after introductions).

Johanna Emeney

A Portable Paradise by Roger Robinson (Peepal Tree, 2019)

The eponymous poem is the last in the collection, and it is the reason why I bought this book. I saw the poem first online as the Guardian’s Poem of the Month. Its first lines are charming; they suggest a way in which we could try to live—wearing paradise as one might wear a pocket watch or handkerchief square:

And if I speak of Paradise,

then I’m speaking of my grandmother

who told me to carry it always

on my person, concealed, so

no one else would know but me.

I love poems that have this intimate sense of the poet’s voice, and I’m also fond of any poem that motivates me to write:

And if your stresses are sustained and daily,

get yourself to an empty room – be it hotel,

hostel or hovel – find a lamp

and empty your paradise onto a desk

Robinson’s book deals with a number of serious and weighty issues: the Grenfell Tower disaster; a premature baby’s fight for life; police racism. However, underlying so much of his poetry is an undertone of hopefulness grounded in people’s ability to choose empathy and kindness. As a result, there is a prayer-like quality to many of the poems—especially those written according to a rhyme scheme.

Robinson is quick to praise the goodness in people, and deft in delineating their characters in just a few lines. One heartening poem is named after the nurse who cared for his baby son:

On the ward I met Grace. A Jamaican senior nurse

who sang pop songs on her shift, like they were hymns.

“Your son feisty. Y’see him just ah pull off the breathing mask.” (“Grace”)

In A Portable Paradise, even the smallest poems are replete with meaning and image, because Robinson’s similes are so nuanced. My favourite short poem is “Boys Light Fireworks on the Ground Floor of Gardiner House Estate”:

They light the fireworks

like candles on a birthday

cake they’ve never had.

This collection won the T.S. Eliot Prize last year, and John Burnside, chair of the judges, lauded it for “finding in the bitterness of everyday experience continuing evidence of ‘sweet, sweet life’.” I couldn’t have put it better myself.

Fiona Farrell

I don’t have a whole collection – just a couple of lines.

That passed away.

This also may.

They’re like a little stone in my pocket, something I find in my hand when events are threatening to overwhelm. They calm me.

I don’t recall any detail of the poem they come from: it’s called Deor, after the man who was supposed to have written it. He writes that he was a minstrel in a secure position but has lost his job to a better poet, so he recounts a whole series of catastrophes that have happened to other people in history and legend, ending each with those two lines.

paes ofereode

pisses swa maeg

I can’t do the thorn on my keyboard, so I’ve had to use a ‘p’, nor the elided a and e, but this is more or less how I read it first.

I didn’t read the poem out of some deep love or attraction, but because Old and Middle English were a compulsory part of an English degree at Otago in 1966. But those two lines have stuck, and they help.

Jordan Hamel

Tracey Slaughter – Conventional Weapons (VUP) – 2019

It’s like/a cathedral to all/we’ve done wrong. – the mine wife

Tracey Slaughter’s Conventional Weapons has occupied a special place in my backpack over the past 6 months. Where other things swap in and out, food, pens, spare underwear, this collection has lingered, refusing to grow stale and weary like the old mandarins I’ll inevitably fish out from time to time. This collection means a lot to me. I reread it with regularity, always finding something different and revealing, something that changes and informs the next reading, like peeling off old scabs to get your first look at new skin.

There are several fulsome, insightful reviews of Conventional Weapons (including Paula’s) that I won’t attempt to recreate here, other than to say it uses texture, rhythm, and space to give certain traumas the visceral and stark examination and exploration they deserve. It feels less like staring into the void and more like resting carefully inside it, swapping histories and rumours, memory and music with anyone else who decides to jump in. Virus or no virus, you should definitely jump.

Anna Jackson

I often turn to poetry for solace, as a way of looking not for solutions but to hold open a space for feeling. Solutions are important, but we don’t always have them to hand, and in the meantime, we have to keep living, and poetry helps. Oddly I often find the bleakest poetry the most consoling, or at least, the only thing I want to read sometimes, and it is in part the rhythms I read it for – there was a time when I wanted to read Robert Lax’s poem of refusal and longing, “the port was longing,” over and over again.

On a much larger scale, Alice Oswald’s radical compression of the Illiad, as Memorial, similarly holds open a space for grief now and beyond the present, with her sustained focus on the deaths of soldiers in the Trojan war, a war almost three thousand years distant from our time. Like “the port was longing,” it works with an insistent rhythm, a rhythm built around repetitions. Oswald cuts out the main narrative thread of Homer’s Illiad, removing the plot, “as,” she writes, “you might life the roof off a church in order to remember what you’re worshipping.” The poem begins with a roll call of all the fallen soldiers whose deaths will be the focus of the rest of the collection, the long list of capitalised names having the appearance of a contemporary war memorial. Each soldier is then given his narrative moment in turn, a description of how each death occurred, followed by a metaphorical image giving another way of imagining the death, another way of feeling it again. And then this metaphorical image is repeated, and its full force felt.

I’ve been looking for the rhythms of poetry lately in prose, too, and finding these rhythms in works like Heather Christle’s essay-memoir, The Crying Book, and Jenny Offill’s novel in paragraphs, Weather. There is a holding open of a space for grief not just in the content – often tangential, often funny – but in the rhythms, the repetitions and returns, the fragmentary feel of a life lived in pieces, with the gaps in between offering a space of resonance where feeling can be felt.

Ash Davida Jane

Mary Oliver’s New and Selected Poems: Volume One. Published by Beacon Press, 1992.

This answer might seem obvious, but I’m constantly turning to Mary Oliver for solace. This collection (which imo is her at her best) has been with me for years. There’s something about her unfailing, candid–but never clichéd–devotion to the natural world and everything in it that helps me get out of the whirlwind of my own head, and remember that somewhere else, for any number of living things, life carries on as normal.

Lynn Jenner

One night at the after hours doctor by myself I felt Poems in the Waiting Room was the hand of a friend. It was something that spoke to me in my language. Being Aotearoa I even knew one of the poets so she was there with me as well as her poem.

I happen to be camping in a friend’s former cowshed at the moment because I’m between houses. The only thing I’m reading is real estate ads and scary virus stuff and most of my books are packed so for now I can’t provide quotes.

But I have kept out Selected Poems of Bill Manhire. I haven’t opened it but I could. That is a comfort.

Simone Kaho

I turn to Bunny by Selima Hill.

It is my go-to book in life in general, which I find carries plenty of little-daily-distresses, as well as a time of serious, global distress like we’re in now. It comforts me because it’s so accessible, and yet stimulating at every level, visually, sensually, intellectually. It has shock, drama, and mystery, with a vulnerable protagonist, in implacable danger. Bunny blends a childlike worldview and fascinations, with an adult sense of knowing, and acceptance. These two forces fight each other, play, and co-exist; resignation and resistance, anguish and escape, danger and relief. Selima’s book captures the essence of human survival, without the sacrifice of imagination. To read it is to feel whatever I feel right now, has a place and deserves to exist and be felt by me, no matter how dreadful it is, or contradictory or naive. I’m so grateful this book exists.

Fiona Kidman

Opened Ground Poems 1966-1996 by Seamus Heaney, poems from a man who opened not only the dark ground of grief, but opened his heart to the world, the turning skies, the joys of life, birth, the every day and the profound, the miracles of our existence on this planet, all of which I believe we will know again when this dark time has passed.

Renee Liang:

Hone Tuwhare, Deep River Talk: Collected Poems (Random House)

My sister sent me this book when I was working in the UK in my 20s. It was in a care package along with a beeswax candle and some NZ chocolate. It was winter in Watford, all the doctors in my hospital were overworked and we barely saw the sun. I lay on my bed to read Hone’s delicious words and felt Aotearoa, its warmth, its quirked eyebrows, its quick wit and deep connection seep back into my core.

Some years later I lost my partner, the man I had loved deeply for eight years. He died young, of a brain aneurysm. When I returned to my job in the outback, I carried this book and other poetry books with me. I clung to them. Tears flowed out; words flowed back in. When I had gathered enough words I gave them homes on paper. I read my new poems to my poetry friends at pubs in Broken Hill. And that’s how I started reading my poetry in public.

Emer Lyons

solace

i’ll call you up in this apocalypse

(definition: great imminent prophetic revelatory disaster)

read Marilyn Hacker’s Love, Death and the Changing of the Seasons:

‘If that’s perverse,

there are, you’ll guess, perversions I’d prefer’

no hello or nothing

the only talk requests for repetition

at the end of part one i’ll stop

you’ll pick up Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts:

‘Of course there exist people who perform intimacy in ways that are fraudulent or narcissistic or dangerous or steamrolling or creepy, but that’s not the kind of performance that I meant, or the kind I mean. I mean writing that dramatizes the ways in which we are for another or by virtue of another [Butler], not in a single instance, but from the start and always.’

i’ll learn to fuck you and the page in ways new

Bill Manhire

Whenever people talk about consolation and poetry, I find I have mixed feelings. I certainly can’t think of a single book of poetry that works for me. The last line of Derek Walcott’s ‘Sea Grapes’, with its powerful caesura, always comes to mind: ‘The classics can console. But not enough.’

I can think of lots of individual poems, though. A big one for me is Charles Causley’s ‘Eden Rock’, where comfort exists as a kind of slow-motion surprise:

They are waiting for me somewhere beyond Eden Rock:

My father, twenty-five, in the same suit

Of Genuine Irish Tweed, his terrier Jack

Still two years old and trembling at his feet.

My mother, twenty-three, in a sprigged dress

Drawn at the waist, ribbon in her straw hat,

Has spread the stiff white cloth over the grass.

Her hair, the colour of wheat, takes on the light.

She pours tea from a Thermos, the milk straight

From an old H.P. Sauce bottle, a screw

Of paper for a cork; slowly sets out

The same three plates, the tin cups painted blue.

The sky whitens as if lit by three suns.

My mother shades her eyes and looks my way

Over the drifted stream. My father spins

A stone along the water. Leisurely,

They beckon to me from the other bank.

I hear them call, ‘See where the stream-path is!

Crossing is not as hard as you might think.’

I had not thought that it would be like this.

Emma Neale

I would recommend any one of the Bloodaxe Real Poems for Unreal Times anthologies – Staying Alive, Being Alive, Being Human. When our reactions and responses are ricocheting all over the place, a generous anthology like this, with multiple authors from all around the world, and with clear thematic sections, can offer something up for all the fluctuations of high emotion. One of the beauties of this sort of title is that it offers up a kind of treasure hunt list of authors whose publications you can go on to read later. I re-read anthologies like these every now and then, always realising there were poems I had skipped before, and also realising that poems that I didn’t feel stimulated or charged-up or calmed or altered by before, can suddenly seem relevant and refreshing, as my personal and our global context is ever shifting. I see there is a new title, Staying Human, due out in October – something to look forward to.

Doug Poole

As Far As I Know – Roger McGough – Penguin, 2012

“Take comfort from this.

You have a book in your hand

not a loaded gun or a parking fine

or an invitation card to the wedding

of the one you should have married”

– Roger McGough – ‘Take Comfort’

In his collection As Far As I know Roger McGough contemplates loss, memory and aging. Then distracts with poems full of wordplay and dead pan humour. McGough can be playful, silly, then harrowing and chilling. The collection twists and turns; from lament to dad joke. All with the flick of a well directed quip.

As Far As I know is a wonderful distraction, and yet deeply moving. ‘Another Time, Another Place’ recalls a childhood memory in two voices of differing perspective – the observer and the observed. ‘Indefinite Definitions’ – then takes you into a game of wonderful word play and frankly, silliness. It is a collection of poems that have the ability to move you. Then pull a laugh out of you – often to your surprise. In these uncertain times – as Roger consoles – ‘you have a book in your hand. Take comfort from this’.

I chose this book for the very simple reason – I enjoy his poetry and have done since my early teens. I feel Roger McGough earnestly writes to bring life, truth, irony and humour to his readers. I enjoy his very original voice and commentary with regard to the human condition.

Chris Price

Luckily for us, books mean we’re never completely isolated. The classics can be consoling in difficult times, and two contemporary poetry collections with their roots in the classics seem like they could be of service right now. Ian Wedde’s Commonplace Odes (2001) is a collection that considers mortality while prizing friendship, good company and good art – all valuable commodities at a time like this, commodities that can’t be bought, but can be savoured in the reading. And Helen Rickerby’s How to Live (on the 2020 Ockham shortlist) digs into lives of women past, some insufficiently remembered (Hipparchia), others famous (George Eliot), to find connection and instruction in the lives of literary ancestors. As it happens, the collection also provides some advice on ‘How to live through this’.

essa may ranapiri

Keri Hulme’s STRANDS (Auckland University Press, 1992)

A beautiful collection of poems that take place in the interstice. Starts off in a lagoon and moves through language and place with a languid pace that really forces the racing mind to slow. I would sit in the light of the setting sun and read these poems out loud to myself and hang on to each syllable.

Ah, sweet life, We share it

with cancers and tapeworms

with bread moulds and string beans

and great white sharks…

Reihana Robinson

Saturday Night at the Pahala Theatre by Lois-Ann Yamanaka springs to mind as a fraught raw read but

Don Paterson’s Rain is both contemplative and heart knocking

Hera Lindsay Bird pours down “like cool spring rain”

Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky With Exit Wounds strikes lightning and

ALL of Manifesto Aotearoa especially the poem I wish I had written

Tusiata Avis’s ‘I cannot write a poem about Gaza’ that contains the title in its first line and continues “because I cannot eat a whole desert.”

And Sue Wootton’s poem that ends with “So as to dissolve under the tongue/of the enemy, so as to restart the heart. “

The poems I return to for solace in my imagination and memory are those learned by heart from James K Baxter’s book of children’s poetry The Tree House

“Oh what a worry when the gorse bushes catch

Somebody careless dropped a match…”

But Vana Manasiadi’s The Grief Almanac resonates with fibre, not like the rope that slowed the sun but fire through a high tensile wire…

I also catch a quirky protesting innocence (aghast comes to mind) and a bright intellectual gaze ( and not just because I love the curves and shapes of the Greek alphabet)

And the limping or lame delayed art of war but that harbouring of the loaded ammunition exposes both a vulnerability and it reminded me a lot of Sally Rooney‘s Conversations with Friends that I just finished with relish and delight

‘But hark the time-bomb of shivering air’ oh if that does not smack of dramatic 16th century blossom I don’t know what does

I love the story story on the left-hand page that grounded my reading giving me solace and energy to unravel the stressful right hand side well only stressful to me because whenever I see extra spaces on one line I’m always falling into that it’s like a big Long breath

‘We can’t unsee it’

Jack Ross

The book I’d like to recommend is an oldie but a goodie, W. B. Yeats’s 1928 masterpiece The Tower. It’s just a fantastic collection from beginning to end, starting off with the magnificent ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ and going on to ‘Leda and the Swan,’ ‘Among School Children’ and many other classics.

The reason I’m finding it particularly timely is the sequence ‘Meditations in Time of Civil War’ which lies at its heart.

An affable Irregular,

A heavily-built Falstaffian man,

Comes cracking jokes of civil war

As though to die by gunshot were

The finest play under the sun.

Ireland in the 1920s did its best to pull itself to pieces: murderous gunmen behind every hedge, even after the vile British Black and Tans had left the picture. Yeats tries his best to make sense of the whole crazy picture, but cannot. I ‘turn towards my chamber, caught / In the cold snows of a dream.’

It’s a wonderful, wonderful book. I wish I could go back in time and read it again for the first time. But it always repays rereading. Worse shocks were to come — the Great Depression was just around the corner, but Ireland (‘great hatred, little room,’ as Yeats put it elsewhere) had already endured its own multiple catastrophes by then:

We had fed the heart on fantasies,

The heart’s grown brutal from the fare;

More Substance in our enmities

Than in our love; O honey-bees,

Come build in the empty house of the stare.

Michael Steven

Ninety-Fifth Street by John Koethe.

Koethe’s sense of memory and time brings to mind Proust and Wordsworth. This book is a passport to the heart.

Simon Sweetman

“Now and Then…” by Gil Scott-Heron

I was introduced to the world of Gil Scott-Heron by Paul Ubana Jones. On one of the many nights when I saw Paul perform he decided to do an a capella cover of ‘Home Is Where The Hatred Is’ by Gil Scott-Heron.

I’d heard the name, as people always say, but I’d yet to hear any of the work. I was instantly floored. By the rhythm and movement and meaning of the words. The very next day I bought this book and – in a separate purchase at a separate store – I bought a CD of Gil Scott-Heron’s recorded music. That was some 20 years ago and his words for the page and his songs for the stage are something I keep near and dear to my heart always. There’s so much to love in this collection – so many individual pieces, it’s both a book of lyrics (since many of them were recorded as songs) and a collection of poems. My favourite thing about Gil Scott-Heron was how flawed he was, and how open he was about that – and about his anger and ooet polemic. How someone could write Home Is Where The Hatred Is and then go back to junkiedom was, at first, beyond me. Now as I re-read and re-listen I’m reminded of how fragile we are. Sorry, to quote Sting there in the discussion of a serious poet.

“Home was once an empty vacuum that’s filled now with my silent screams”.

Thanks Gil. Thanks Paul.

Mere Taito

Can poetry be a form of solace?

Yes, absolutely. An example of a poetry collection that has the effect of slowing me down, and making me reach for the silence buried beneath ‘all the noise’ is Yoko Ono’s anthology titled Acorn (2013) published by virago.

Her poems are themed by Sky, Earth, City, Connection, Watch, Room, Cleaning, Sound, Life, Dance, Questionnaire, Quiz, and End.

In ‘Sound Piece III’, readers are asked to:

Listen to your town breathing.

1) at dawn

2) in the morning

3) in the afternoon

4) in the evening

5) before dawn

Her poems have a restful, meditative quality. I go here to be still. And to listen. The poems are also paired with clever dot drawings. Check out the images of the dot drawings here

Chris Tse

Recently I re-read Charles Simic’s prose poetry collection The World Doesn’t End as preparation for a workshop. It’s the first book that came to mind when I was asked to recommend something for this list, partly because its title is a mantra we can use to keep ourselves calm during these strange days, but also because I’d forgotten how delightfully strange some of its images are: dogs at dancing school, a father singing in a bathtub, ‘big-hearted trees’, people riding UFOs. It’s a bizarre collection for sure, but one that can lift the spirits and dazzle with its unique view of the world.

Tim Upperton

I’m sceptical of poetry’s efficacy – when Shelley says poets are the ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world,’ it’s the word ‘unacknowledged’ that rings true. But some books of poetry act like a tonic, even on gloomy me. Read Bill Manhire’s Lifted, and maybe learn its last poem, ‘Kevin,’ by heart. And read The Collected Poems of Kenneth Koch or of Frank O’Hara for some unalloyed happiness.

Ian Wedde

Yes poetry can be a solace but may be a wake-up rather than a pat-down. I treasure a small red Alpha Classics edition of Ovid’s Metaphorphoses – An Anthology selected and edited by J.E. Dunlop, published by G. Bell & Sons in 1961 when I was fifteen, which was about when I began to be really obsessed with writing poetry. It was a school text and cost six-and-sixpence which would have been refunded so long as the book wasn’t ‘unreasonably battered, dirty or torn’, as the inside-cover admonished. I didn’t return it. There are eighteen pages of uninspiring introduction, thirty-two pages of selected odes in Latin, and one-hundred and twelve pages of notes and vocabulary. I can’t really read Latin any more but when I turn a few of the thirty-two pages and make the shapes of the dactylic hexameter words of Publius Ovidius Naso (43 B.C. – A.D.17), a ghost enters the room and stands just out of sight. It’s probably not Ovid, could be me aged fifteen, but more likely is J. E. Dunlop, Rector of Bell-Baxter High School in Cupar, Fife, Scotland, hoping that the kid he first met about sixty years ago will get why the feel of these barely understood words in his mouth might be just what’s needed when the going gets tough.

Elizabeth Welsh

Anna Smaill The Violinist in Spring (Victoria University Press, 2005)

Why I have picked this collection: Anna’s euphonic collection, The Violinist in Spring, hums with a deep, meditative, silvery tone every time I read it. From waking to the blissful smell of frying bread to the communion between a lone fig tree and a power pole to a stray mushroom’s gills being slowly caressed, this rhythmic arc of poems slows down time, focusing on a celebration of the achingly quotidian, asking us to pause, bend and consider warm and earthy moments of pure phenomenological being, and to reach out and grasp them in all their expansive lightness.

Albert Wendt

I don’t want to sound egotistical but on a quick look at your request, I recommend my own poetry collection: FROM MANOA TO A PONSONBY GARDEN published by Auckland University Press. Especially the sequence of poems called “A Ponsonby Garden’. Which is focused on our garden and gardening and old age and impending death and the acceptance of it. When I reread those poems I always find them consoling.

Sue Wootton

It’s the perfect time to memorise a poem to wash your hands by – or, to put it another way, to use the time washing your hands to memorise a poem. Why sing Happy Birthday twice in a row when you could know a sonnet by heart instead? As for a poetry book, I’m going to suggest Learning Human, selected poems of Les Murray. Murray’s vision is singular and startling, glorious and life-affirming.

This is the first in my new series. I phone a NZ bookshop, they suggest a NZ book, I add my NZ pick, and they pop the books in the mail for me. I am using my Wellington Writers Festival fee to spend on books.

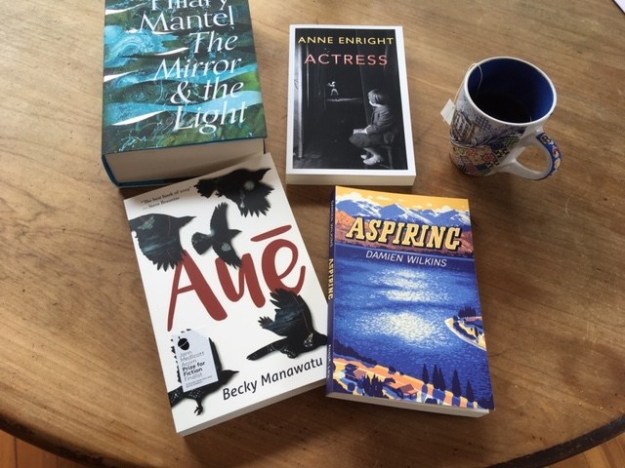

Carol Beu, from The Women’s Bookshop in Auckland, recommended Becky Manawatu’s Auē (Makāro Press, 2019), shortlisted in the 2020 Ockham NZ Book Awards Fiction Category. She enthused about this gripping narrative – and I had already been tempted by reviews. I picked Damien Wilkins’s YA novel – Aspiring (Massey University Press, 2020). The book was unable to launched in the traditional sense so newsroom posted Damien Wilkins’s launch speech. To help promote the book I am including a Q & A.

As you can see I never leave a bookshop empty handed and always add a few extras. Two authors I am big fan of got popped in the parcel – so can’t wait to get stuck into new books as I am imposing semi self isolation.

Massey University Press page

Mākaro Press page

First sentence from Aspiring: ‘Pete’s was where I had an after-school job.’

First sentence from Auē: ‘Taukiri and I drove here in Tom Aiken’s truck.’

Damien Wilkins Q & A

Q1: A YA novel! What’s the story here?

I have no idea! At no point did I think ‘I must write a YA novel’. I’d always wanted to write about the Gateway Arch in St Louis, this beautiful and quite strange public monument. I lived in St Louis for two years. The arch always seemed to me to be unconnected to the world. It’s spectacular but also plonked there, as if by aliens. A long time ago, I wrote twenty pages of an adult novel featuring the architect Eero Saarinen, who designed the arch. But I abandoned it. I knew nothing about architecture. Then I wrote a song about him and recorded it on my first record. That was that, I thought. But then somehow the arch came back and got caught up in the story of this New Zealand boy. Nothing is planned!

Q2: Liberating to write, or tough to work within the confines of the genre?

There are confines? I didn’t really think about the genre. This is a book about a young person from a young person’s point of view. Once I’d decided I would never leave Ricky’s mind, the idea of an audience was settled – Ricky is speaking to himself and his peers. I didn’t want this novel to feel like ‘adult fiction writer Damien Wilkins on holiday’. I was always trying to write the best sentences, the best scenes, the most alive story I could write.

Q3: Aspiring … it’s Wanaka, right?

It’s Wanaka put through a filter, sometimes put through the ringer. You touch something with language and it changes. I needed the freedom to say things that are incorrect and even unfair about the real place. I didn’t want the reader to say ‘Oh, he got that wrong’.

Q4: How much time have you spent there and what struck you about the place?

I’ve been visiting and staying there for thirty years. We have family connections. The obvious and true thing to say is that it’s a beautiful place to put a town. The mountains! The lake! And over the decades that beauty becomes a magnet – more people want to be there. Retirees, escapees, people of means, tourists – we’re all drawn there. How to manage that growth? It’s a place of privilege of course, and not very diverse. And I became interested in what happens behind the scenes in a place like that. And what it would be like to grow up there, especially if you don’t really share the values of the place … It’s all probably a thinly disguised version of me growing up in Lower Hutt in the 1970s, except we just had boring hills to look at!

Q5: Ricky is so likeable. To what extent is he an amalgam of all the terrific sixteen-year-olds you’ve come across?

Boys of this age get a bad press. I wanted to write a little hymn to their internal lives. Those lives now seem more compressed, more stressed. There’s a lot of anxiety around. I think it’s disastrous for everyone the way that young males are still educated away from the life of feeling.

Q6: At one stage Ricky thinks, ‘Put away childish things’. That seems all that needs to be said about the fraught process of adolescence, doesn’t it?

If only! I think the novel catches Ricky at this weird moment where his body is outstripping his brain and his emotional resources – his sudden tallness and bigness gives him access to an adult world he’s not ready for. He grieves for his old life as a child but is also excited by and drawn to the possibilities of the future. He knows, however, that the planet’s future is dire. But there’s something else too. I mean, it’s not as if Ricky’s dad is a model of emotional maturity. I hope the novel gives a picture of people of all ages in the process of becoming, of trying to work out things, of trying to shift. I don’t believe in these clear-cut categories of human development – ‘and now you have emerged from the chrysalis!’ A lot of us still have bits of chrysalis stuck in our hair.

Q7: It’s such a painful time but do you also envy your characters their youth?

Of course! I’m old. I have two daughters in their twenties. But then it’s impossible for me to know what it’s really like to be sixteen now. There are lots of signs that it’s not so much fun. I put some of this in the novel. I also wanted to show the resourcefulness of young people, and the endless search for pleasure.

Q8: And they gave you a great opportunity for jokes and whipsmart dialogue.

Kids are quick. I envy the speed of their minds. The dialogue between Ricky and his friends, and Ricky and Keri were the most enjoyable parts to write. If you don’t have power, you still have talk.

Q9: Adults will no doubt end the book feeling protective, even anxious, about Ricky. But what do you think young readers will feel?

I hope they feel that they’ve read about someone who has gone through something and come out the other side not just intact but with a renewed sense of his potential and his power. I’ve always liked that thing that Maurice Sendak said about children protecting adults from the truth. You really don’t want to upset your parents by letting on how much you know.

Q10: Will he be ok?

Hope is important. He hasn’t solved anything but he’s in a relationship, he’s having fun, and his family is in a better place. Ricky has successfully protected his parents from the truth about his life! Good on him.

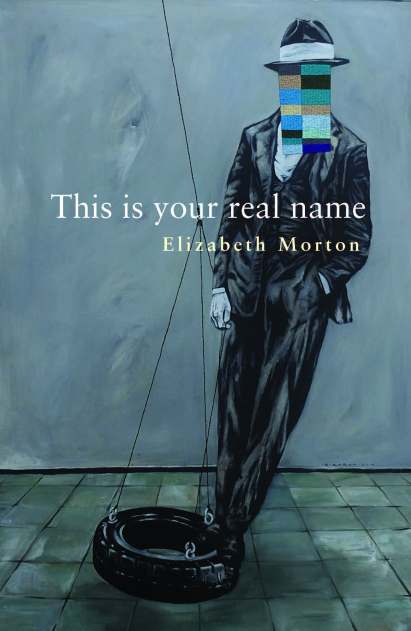

Elizabeth Morton This is your real name (Otago University Press, 2020)

Elizabeth Morton’s launch scraped in by the skin of its teeth recently, but I thought it would be lovely to do an online version and get Poetry Shelf Lounge rolling. You can read and listen for morning tea with a short black, afternoon tea with your favourite tea, or a glass of wine or beer this evening.

At the bottom of the post, I have put a selection of good bookshops where you can buy or order the book online (this is a list in progress, please help me fill the gaps).

Tracey Slaughter launched the book.

Split the pages of Elizabeth Morton’s This is your real name anywhere & you are in the pulsing presence of questions that cut to the very heart of poetry: How much, if anything, can language actually touch? How much of our experience can we ever name? How much can poetry reach past the stars smashed into the emergency-glass of daily-living & offer the kind of voice that leaves more than a bloody trace, that makes a vital difference. ‘Poetry wallows between question marks/police? fire? ambulance?’ says a piece that opens with telephone lines exploding in a gaze pushed to the edge – how much can language ever hope to halt pain, to offer connection, to help in such a crisis? ‘Deep breaths,/say the operator’ within that poem, but ‘inside the communications centre/the desks are inconsolable.’

‘There is no touching the black heat at the centre of things’ another early poem entitled ‘Inside-out’ declares – and yet travel through the bolted internal doors and bleak domestic corridors, the blighted global landscapes and glinting dystopias of Elizabeth’s collection & you know you’re in the hands of a poet who, like Plath or Sexton before her, has all the dazzling surreal command of language to reach to the core of that black heat, to make it speak.

‘Inside-out’ concludes with a widespread vision of ‘a wreckage of stars’ – but the volume goes on in piece after luminous piece to chronicle the work of salvage, of a self bent on using every particle of language to dig through the ruins, rewire the evidence, sustain the spark, relight every shard.

These are poems that speak again and again from both the inside and the outside, from both the blasted solar plexus of private traumas and the slow-mo devastations of the wider planet – over and over the poems flicker from hallways tremoring with personal pain to the ‘casual terrorism’ of history, taking an ‘aerial photograph’ of a suffering earth with the same kind of acute irradiated poetic lens that it turns on the lone & isolated heart. Whether it’s the stranding of a single life caught in the driftnets of personal desolation, or the mass beaching of a populace oblivious to the global damage they’ve done, Elizabeth’s language zeroes in on the waste & makes us see the interconnections: whether it’s steering the reader through burning towerblocks or coldblooded wards, past disinterested drone strikes or through achingly-handled small-scale solo losses, the breathtaking scope of poetic skill with which she charts her urgent scenes makes the reader feel every detail, feel the meds and the headlines catch in our throats, feel the doors locked and the altitude dropping, feel the kiss blown against the quarantine window & the distant ‘circle[s] of blood’ left on political screens.

These are poems that detonate and sing, that ring in the ear and sting in the political consciousness, and linger in the bloodstream long after they’ve stained your eye. They’ll also make you outright belly laugh: ‘I’d marry Finland. I’d blow Nicaragua. I’d shag Australia if she wore a paper bag’ states a slapstick look at politics that plays wicked & sacrilegious footsie with stereotypes. With the same comedic weaponry ‘How I hate Pokemon but I can show restraint and just talk about my adolescence’ gives a gore-soaked rundown of methods to slaughter innocent anime, and ‘In the next life’ tracks Wile E. Coyote speeding to collide with another booby-trapped piano or hurtling freight train. But of course, under the cartoon bloodsport there’s another violence being expressed: ‘I’m from the wrong cartoon she says…There is no/acid in my stomach to digest the sadness’; ‘I spent my teens/hyperventilating in elevators…yanking at emergency cords’ – that’s what lurks beneath the funny foreground of these onscreen critters and their messy calamities.

‘This is not a joke’ warns another poem, parading a cast of backwoods bar-leaners and big boned nobodies, its humour always ready to brim with ‘a metaphor so sad it makes grown men sob and jerk off into the same handkerchief.’ The counterstrike to comedy is always coming, the punchlines always poised ready to gut you. We might snicker when we’re introduced to a blowsy homespun oblivious America, but when she ‘order[s] Big Mac’s and Napalm’, lazily erases continents & watches bodycounts rise from her consumerist couch, the smile is wiped off our faces. And when the pronouns shift in this poem to fold us into complicity, as they do to such clever & ethical effect throughout the collection as a whole, we too are left standing with supermarket bags and shotguns/baffled and alone.’ That moment of aloneness – whether it’s the self turning figure-eights of final need or the last polar bear ‘pacing his cell, as the credits go down’ – is the place which the poems often return us to: ‘I wonder whether you know/you are melting’ this poetry asks with chilling economy. Over and over we find trapped ourselves in that phone booth, as in the masterpiece ‘Aubade’, where the glass is ‘skull-cracked’ and the world seems only to have ‘hold music’ to offer us. But even in this moment of exigency, with our ‘hearts in []our horror mouth’ & all the lines crossed, language is held up as ‘the loneliest miracle’: because we still use it to ‘pray, into the receiver’ hoping for a sign on the other end, some voice to come back from the empty page. ‘Writing is a political act’ the poem insists, even from this place. Even if all it can sometimes do is trace ‘the face of the enemy,’ or chalk round the bodies of selves and lovers we’ve lost; even if all it can sometimes do is echo the bleak dialtone inside our chests, its utterance ‘sets you apart’ the voice of ‘Aubade’ repeats to the sufferer.

Elizabeth had already set herself apart as a poet of breathtaking force, edge, intensity and empathy – This is your real name is another stunning, irrefutable, crucial book, a fearless personal testimony and a blistering political act. It goes to the places we need poetry to go to, places that only a language loaded with heart and shimmering with pressures can name. It smashes the glass.

Tracey Slaughter

Listen to Elizabeth read ‘Tropes’:

Stranding

We were never alone, pushing up loam on a blackened beach.

We kicked our tails like we were trying to escape

the outline of ourselves. We came ashore, two by two

with our cutlasses and compasses, with our baleen smiles

and bad attitudes, with our dead-end marriages and dreams that choked

in drift nets. We were never lost. We knew the shoreline better

than we knew our own purposes. We were a quarter into lives

that stood us up from the water-break, that left us gasping

by the river mouth, blistering under wet sacking,

our eyeballs fierce with the evening sun.

We wanted the attention. We wanted to arrange ourselves

upside down and scattered like something infinite. Like stars.

We follow each other to the end of the beach

and sing something that reminds us of bone

and the million land-flowers our mothers spoke of,

and the kamikaze heritage, our fathers and their fathers,

who recognised a vague phosphorescence

and shadowed it into the salt marshes, dreaming of air.

Elizabeth Morton

ELIZABETH MORTON grew up in suburban Auckland. Her first poetry collection, Wolf, was published by Mākaro Press in 2017. She has placed, been shortlisted and highly commended for various prizes, including the 2015 Kathleen Grattan Award, and her poetry and prose have been published in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States, Ireland, Australia, Canada and online. She has completed an MLitt in Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow.

Otago University Press author page

Let’s support our books and authors. Most importantly you can order this book online or visit your local bookshop. Here are a few choices (new books):

Whangārei Piggery Books Porcine Gallery

Auckland The Women’s Bookshop, Time Out Bookstore, Unity Books, The Book Lover(Milford), Dear Reader

Matakana Matakana Village Books

Hamilton Books for Kids Poppies Bookshop

Tauranga Books a Plenty

Rotorua McCleods

Palmerston North Bruce McKenzie Bookseller

Whanganui Paiges Gallery

Gisborne Muirs Bookshop

Napier and Havelock North Wardini Books

New Plymouth Poppies

Featherston Loco Coffee and Books, For the Love of Books

Carterton Almos Books

Masterton Hedkeys Books

Martinborough Martinborough Bookshop

Wellington Marsden Books Unity Books, Vic Books

Petone Schrödinger’s Books

Nelson Volume Page & Blackmore

Christchurch Scorpio Books University Bookshop

Queenstown BOUND Books & Records

Manapouri The Wee Bookshop (no website?)

Twizel The Twizel Bookshop

Dunedin University Bookshop

Very sorry about this – but yes it is the thing to do. PG

To our lovely book festival supporters,

With heavy hearts we have decided to cancel the 2020 Marlborough Book Festival.

Given the uncertainty around the COVID-19 pandemic, and how long it might affect us in New Zealand, we decided as a committee that the best thing to do is to sit tight for a year.

We thank you for your understanding.

Not to downplay the seriousness of what is happening, but we like to think that we can all do our bit to prevent this condition spreading by staying at home and reading a book. Something we think all our festival supporters will be quite comfortable doing!

Over the winter we will continue to send you newsletters highlighting the work of the 12 fantastic authors who were set to visit Marlborough in July. We do hope they will be able to join us at a festival in the future, so this winter is your chance to read their books before they come.

Thanks must go to the authors and interviewers who were all lined up to come, and to our sponsors and supporters who were all geared up to support another great festival. We will be back!

All our very best to you and yours,

The team behind the Festival,

Sophie Preece, Sonia O’Regan, Sharon Hill, Kat Pickford, Lorraine Carryer, Charlotte Patterson and Claudia Small

Cancelled!

LOUNGE 72 Wednesday 25 March at Old Government House 5.30-7 pm

It will be rescheduled later in the year.

Last year I invited NZ children to write a poem that embraced happiness. This is what Tom wrote. Ah, I just can’t stop reading it. Children’s minds can be free range as well as roving on the beach!

Recipe for Happiness

1. Imagination – let it free.

2. Corn – eat it up.

3. Cheetahs – watch them run.

4. Yellow – let it paint.

5. Science – let it create.

6. Books – read them quiet, read them louder.

7. Exploring – discover and look.

8. Art – colour colour colour.

9. Poetry – be writing.

Tom N Age 11 Year 6 Hoon Hay School/Te Kura Koaka (2019)

Sad but understandable!

After a lot of deliberation, it is with great sadness we announce the cancellation of this event. However, we hope to hold it later in the year so watch this space.

Please spread the word if you have shared it with family, friends and your networks. Arohanui.

7

Halide compounds hum inside the floodlights

pouring down lumens on the prison yard

across the service lane. Sleep is futile.

Antarctic breezes rattle loops of barbed wire.

Pairs of men in dark coats milled from rough wool

make laps of the yard’s fenced interior.

I lean out the window, into the brumal air

of tonight’s vision. The lifers carry on.

They walk their fates in thick woollen coats,

addressing each other inaudibly—

confessing and sanctifying their stories

with hand gestures, glowing tips of cigarettes.

You sleep. It is too late to show you them.

Their cold cells are a museum, open at 9 a.m.

Michael Steven

This is poem 7 from a sequence called ‘Leviathan’ in The Lifers (Otago University press, 2020).

Jeffrey reads ‘7’

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman:

There is a whakapapa of prison poetry that links Michael Steven’s poem on men behind bars in The Lifers, his recent second volume from Otago University Press. The poems in this book have gritty echoes that François Villon would hear and feel; a deep well of humanity also that Oscar Wilde would appreciate, from his cell in Reading Gaol. Whether we are watching users scoring, thieves preparing a raid, a friend mourning the suicide of a kindred lost soul, there opens up before us a vision of brokenness elegised with compassion through an unsparing binocular lens. The poem considered here – Sonnet 7 from a series, Leviathan – captures precisely the cold realities of those sentenced to life for the most serious of crimes. The effect is so visual, it returned to me a memory of Van Gogh’s ‘Prisoners Exercising’, painted in 1890 while he was in the asylum at Saint-Rémy, suffering deep depression. Most Fridays, with two other poets, Bernadette Hall and Jeni Curtis, we take part in a reading group at Christchurch Mens Prison; I recently took copies of this poem and shared it. The silence that greeted its reading attested the truth Michael Steven has captured, from the inside. This poem – and the rest of his fine and developing oeuvre – invite your close attention.

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman is a Christchurch poet and non-fiction writer. His most recent poetry collection, Blood Ties: selected poems, 1963-2016 was published by Canterbury University Press in 2017. A memoir, Now When It Rains came out from Steele Roberts in 2018. He is currently working on a book chapter for a collection of studies on early 20th century ethnographers. He makes his living as a stay-at-home puppy wrangler for Hari, an eight-month old Jack Russell-Fox Terrier cross. Hari ensures that very little writing happens, but Victoria Park is explored and mapped daily.

Michael Steven is the author of the acclaimed Walking to Jutland Street (Otago University Press, 2018). He was recipient of the 2018 Todd New Writer’s Bursary, and his poems were shortlisted for the 2019 Sarah Broom Poetry Prize. He lives and writes in West Auckland. The Lifers (Otago University Press) was recently launched at Timeout Bookshop.

Otago University Press author page