Welcome to AUP New Poets 6 launch. Settle back with a glass of wine or a cup of tea and enjoy the launch. You can order the book from your favourite bookshop once they are open. The book is beautiful – I can’t wait to share my thoughts on it soon.

Congratulations Anna Jackson, Vanessa Crofskey, Ben Kemp and Chris Stewart.

Cheers!

From publisher Sam Elworthy:

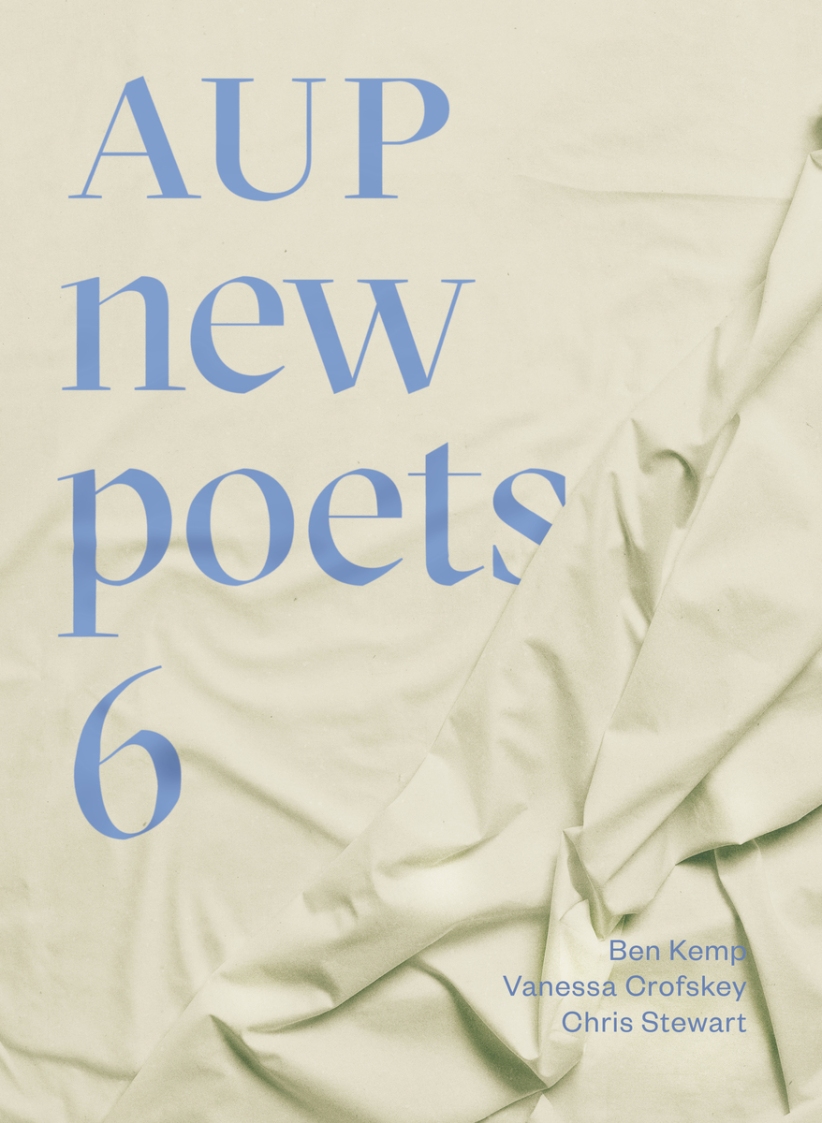

Thanks to editor Anna Jackson’s mighty work, AUP NEW POETS has come back with a bang. And in AUP NEW POETS 6 (our second in the new format, this time a book in rumpled bed sheets), the poets turn things inside out and upside down. Ben Kemp, our first poet coming down the line from Papua New Guinea. Vanessa Crofskey, our first poet to lead us to include fold-outs and colour in a poetry book (and excel graphs and arrival cards). And Chris Stewart, well his poetry is from Christchurch as a husband and a father, which may or may not be a first for us but we like it very much.

So I’m sorry that our launch can only be virtual because I would have loved to see Vanessa and Chris in live action (and Ben coming in over the ether) but thanks to Paula for hosting us here and to the great team who made the book: editor Nic Ascroft and proofer Louise Belcher; designer Greg Simpson; Creative New Zealand for the funding and the lovely AUP team, Katharina Bauer, Sophia Broom and Andy Long.

From editor Anna Jackson:

This is a collection of poems that deserves a party so thank you to Paula Green for organising this poetry party on Poetry Shelf, and thank you to Time Out Bookstore who would have been hosting an actual launch with people actually at it, if we weren’t all now in lock-down. They can’t process orders now but please remember to support the bookshop and support the poets by placing an order that can be filled after the lockdown is lifted.

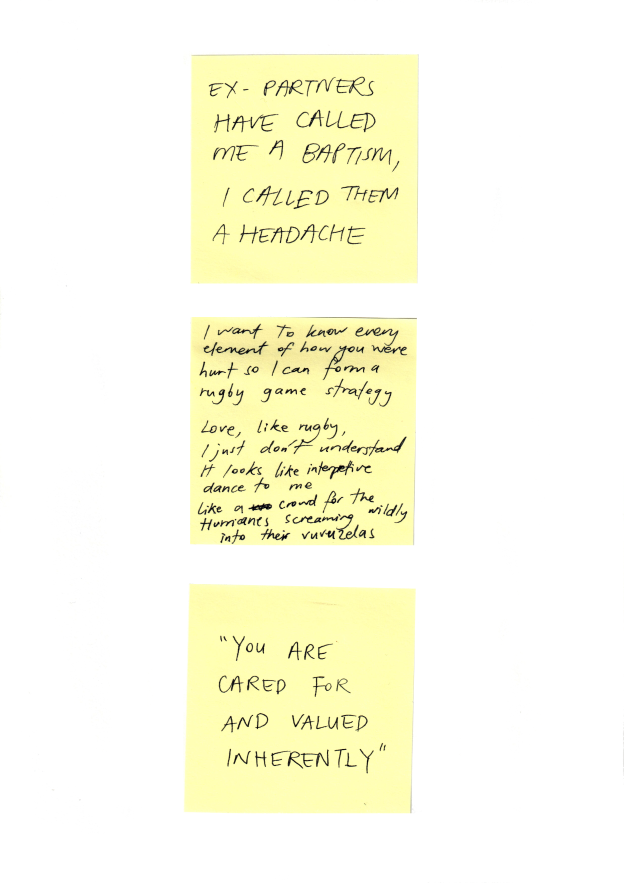

I love this collection, which brings together three such different poets as Ben Kemp, Vanessa Crofskey and Chris Stewart. It moves from Ben Kemp’s slow-paced attentive readings of place and people, in a selection moving between Japan and New Zealand, to the velocity of Vanessa Crofskey’s fierce, funny, intimate and political poetry, which takes the form of shopping lists, post-it notes, graphs, erasures, a passenger arrival card and even *poetry*, and finally to Chris Stewart’s visceral take on the domestic, the nights cut to pieces by teething, the gravity of love and the churn of time.

There is so much in this anthology, poems about whale strandings, teething, dispossession, loss, the pain of physical exercise, the embarrassment of swimwear, the gravity of responsibility, the love you feel with the shiver of your skin, friends to watch Ferris Bueller’s Day Off with a parent to the rescue, cherry blossom, the chatter of 10.000 sea-gulls, clean sheets, rice, bathing a child, white washed pages, red ink and more. We need poetry at a time like this and if we can’t buy books, we can read the books we have, and if we run out of books, we won’t run out of poetry on the internet, and if we have to self-isolate, we don’t have to be alone.

Thank you to the poets for their poetry, to Sam Elworthy and all the team at Auckland University Press and to editor Nick Ascroft, for bringing this book into the world.

Poet Erik Kennedy says a few words and reads a poem by Chris Stewart:

And now for the AUP poets (Chris Stewart, Ben Kemp and Vanessa Crofskey):

Chris Stewart reads three poems:

Ben Kemp reads:

Vanessa Crofskey reads ‘I used to play the silent game even during the lunch breaks’

Ben, Chris and Vanessa in conversation

Chris to Ben: You make links between cultures in your poems. What ideas do you want to ‘get at’ in this way?

When I was a child, we used to visit the local marae every Wednesday and listen to the elders tell stories. These experiences really shaped me. The stories were mystical and deeply embedded in the natural world. Years later, I came into contact with the films of Akira Kurosawa, and I was immediately struck by a familiar energy. I explored Japanese film, theatre and literature for a number of years, and began to explore ways to fuse.

The Fauvist movement, and particularly the paintings of Paul Gauguin also greatly influenced me. The contrast and the juxtaposition of colours has always inspired me. In poetry, the concept of plucking two unfamiliar images from different cultures, and placing them alongside each other often creates a fascinating reaction, and a new energy.

As artists, we are all searching for new ground. In poems, we endeavour to express emotions in a new way, constantly exploring alternative perspectives and all the space in between.

Chris to Ben: I like how you use space in your poems (e.g. the poem oto (sound)). How important do you think space on the page is to a poem, and what informs your choices about that in terms of form?

Miles Davis claimed that the most important notes were the ones you don’t play. Every word must serve a purpose and be innately linked to the whole of the poem. For that reason, I spend quite a lot of time on the editing and refining process. I like space, and the careful arrangement of the poem on the page creates breathing space for the eye. I also often use space to replace punctuation because it declutters the page.

Chris to Ben: The essence of I seems to have some connection to song of myself by Walt Whitman. What parts of Walt Whitman appeal to you, and how do you think they appear in your poems?

Both Walt Whitman and Henry Miller outlined a process where the person must die in order for the artist to grow from the ashes. I had a similar experience in my early twenties. Both writers have been influential on me. Walt Whitman, because he so acutely mined his own consciousness, both evolution and devolution. Whitman is a celebration of everything that is light and dark in the human spirit. The other aspect of Whitman that I have always enjoyed is the way he is able to weave tenderness, fragility, intimacy and brazenness. His lens is so wide, but he is able to pull it all together into his single stream of consciousness.

Chris to Ben: My favourite poem of yours is Ranginui’s tomb. I loved the flow and sound of the sentences, but can you expand on what meaning the last line ‘the tree that grows in someone else’s garden’ has for you?

I guess the line is more a reflection of my own feelings of displacement i.e. being both Maori and Pakeha. I love humanity and hate it at the same time. I will often draw humanity in with affection, then in the next line, throw it away in disgust. I fear for the environment and our disregard for it horrifies and frightens me. Personifying the natural world enables me to express how poorly we treat it. I used Maori gods and placed them in an unfamiliar setting, in order to sharpen a sense of displacement.

Ben to Chris: In Gravity (btw it’s stunning) It seems you’ve drawn on the place and experience before birth. Why were you drawn there?

OK so what happened with that was there was a very clear trigger for that poem, and it was the birth of my second daughter. It was supposed to happen in hospital… but it happened on the veranda on the way to the car. Luckily, the midwife was there! It went waaaay better than the hospital birth for our first daughter – Jo (my amazing) said it was kind of a healing experience for her. Gravity was more drawn from the place and experience of the immediate post birth: The midwife was fiddling around with the placenta (we’ve still got them in our freezer!) and commenting on what it looked like and what it meant. It reminded me of some sort of neolithic wizardy person reading the rune stones, and I thought that I could write a poem about that kind of cosmic stuff. I mean, childbirth is kind of a cosmic experience. Of course that was just the trigger, and you do tend to go away from the trigger a bit in the writing process. I did feel a bit like I really had to get it down; the initial brainstorm happened very quickly, but it took me about three months to work on it. It was one of those poems that was like an ice sculpture; the big block of ice was frozen in place quite early, and the chipping away of small pieces around the edges happened bit by bit over time until I kind of just knew it was done. A big shout out to the Sweet Mammalian crew for selecting it (Hannah Mettner, Magnolia Wilson, and Morgan Bach); I think it was the second poem that I ever got published, and it really made me think, ‘yeah, I can do this’.

Ben to Chris: How do you develop the rhythm and structure of each poem? Is it instinctual? Why have you chosen not use commas throughout?

Yes. I think it is instinctual. I do think that people must just have their own sense of rhythm that comes out in their writing style, in the same way as you can listen to some people talk, and others: not so much… I don’t set out to write ‘rhythmic’ poetry – I do try to work with symbolism and imagery purposefully, though. I definitely edit stuff if I think it needs to ‘sound better’ or if there are awkward sentence structures that need ‘smoothing out’.

The commas thing: well, I don’t usually like using punctuation at all for a variety of reasons. Firstly, punctuation is used to make things clear when clarity is a primary purpose. In poetry, I don’t think clarity is a primary purpose; there are a lot of interesting effects that happen in the reader’s mind as they read without punctuation. I also want the line break to do work: surprise, ambiguous meanings, pace etc… In saying that, I do shy away from finishing and starting different sentences on the same line without full stops. The poem ‘mummy’ is one example of where I’ve done that, though – I think that’s more about pace than meaning. Punctuation tends to ‘direct’ the reader, and I don’t want to do that. Kerrin P Sharpe is a NZ poet who really goes to the limit of the whole ‘say no to punctuation’ thing. If you want to get a sense of the effects it can create in terms of ambiguity and pace, check her stuff out.

Ben to Chris: Stepping back from poetry, how has the birth of your children changed and reshaped you as an artist and a person?

As an artist: I manage my time better! Being a creative person, it’s really difficult to settle into a creative process. It takes a lot of brain space to organise yourself in order to create art… I get very little time that I can actually allocate to that; it’s usually between 8-10pm, and I’m usually buggered from the non-stop day, so unless I have a specific idea for a poem that is churning away and I’m really motivated to drive that forward, I just don’t do it. I find I write my best stuff if I’ve been thinking about poetry and writing regularly for at least a couple of weeks (I’ve heard it called ‘oiling the machine’), and sometimes I’m in that mode, and sometimes I’m not. It happens in fits and starts. Poetry / writing is definitely something that I come back to and is there in me; it will always come out eventually.

As a person: my priority is family. Every decision I make is about ‘how will this affect my family?’ That includes putting work and writing behind that. I feel quite guilty if I think I’m not ‘present’ for my kids. In saying that, as a secondary school teacher, I often feel I put more energy into other people’s kids than my own kids. Also a source of guilt. When I get home I’m often too tired to really give them the best of me. I’ve started to have very little patience for people who waste my time, too, because having kids means you have to be efficient if you want to achieve anything.

Ben to Chris: Why do you write poetry? What drives you? What does the craft give you in return?

Fantastic question. I write poetry because I want to make things. I like making things out of words – things that sound cool and mean something. Sometimes I kind of just get a feeling that I want to bash certain images together or that I want to write something about something-or-other, and I can’t get rid of the urge until I’ve sat down and got it out in a poem. It can actually affect my relationships, like, if all I want to do is sit down and write a poem, and someone else needs me to do something, then I can get quite irritated. The craft gives me what people often call ‘flow’. I get that when i’m in the middle of writing something and it gets to the point where the language I’ve gathered starts to fit together and it all seems to drive itself. I think writing is like putting a puzzle together, but you have to create the pieces yourself as well. That’s the fun bit. I enjoy the feeling of potential when I sit down to do a poem.

Chris to Vanessa: The poem PTSD memes for the anxious / avoidant teen: I find the grid form quite innovative. What effect do you think that adds to the poem? How is it different to other structural techniques that you could have chosen to separate the units of meaning within the poem?

The structure of this poem had to be split up to accommodate page sizing, but it is meant to be like a Bingo grid!

I was inspired by the bingo memes I saw all over the internet that related common experiences to each other, it seemed like a way to confess certain behaviours or feelings without making yourself isolated or vulnerable.

So I wanted to replicate that in my poems to be able to speak about how I felt about something personal, which was sexual trauma.

Chris to Vanessa: Some of your poems seem to be ‘getting at’ the subject of ‘identity politics’ (e.g. every time auckland council says ‘diversity targets,’ my phone vibrates). What do you think your poems are saying about that?

I think identity politics in general can be a bizarre and wild minefield to navigate. It is one I feel aware of in my everyday experience.

I think it’s ironic that people own your identity more than you do yourself. I suppose I’m writing from a place of only just beginning to know myself and yet it feels like that is such a public journey, people put things and assumptions on you before you even make the first step. So you’re always battling against something or clearing away the debris before you find your pathway.

Chris to Vanessa: ‘peak hour Kmart lines of salmon dancing’. I love the surprising imagery and incongruous juxtapositions in your poems. What work do you want juxtaposition and imagery to do in your poems?

I have ADHD so I think I just jump around in my brain anyway!!!! Lol. I suppose I’m interested in breaking up the narrative tone people assume, or the given pathway of a poem. I like using metaphor and imagery to surprise people, which makes them have to reorient themselves in a written landscape. You can take someone anywhere.

Chris to Vanessa: In the poem ‘Beauty‘, I’m interested in the ‘redaction’ technique you’ve employed. What effect do you want that to create for the reader?

I think I wanted to make my process of retraction and deletion visible, to show the process that occurs prior to a surface feeling smooth.

I think that’s what beauty feels like to me, dangerous and bumpy, so it didn’t make sense for the way it was written to be glossy. I want people to think about what’s been removed and hidden, and perhaps why.

Vanessa to Chris: Ben might have asked u this already!!! But what draws you to lowercase? Is there anything in particular that makes you feel more comfortable using a more casual style of grammar?

Hhmmm… yep. I do feel comfortable using a more relaxed style of punctuation because it opens bits of a poem more to interpretation – I don’t think my grammar is casual, though. I do try to make my sentences sound ‘correct’. But the lower case thing… I guess what I’d add to my answer to Ben’s question would be I think some poets, for example Nick Ascroft is one, use capitals at the beginning of every line, and I think this might be an appeal to tradition… Maybe I don’t really care about tradition? I like to strip it all back to the essential nature of words themselves. I was told to use capitals for words like ‘Russian’ and stuff like that, though, and I didn’t mind that. There are a couple of poems in there that I’ve punctuated ‘correctly’.

Vanessa to Chris: I am interested in how the domestic unfolds into the astronomical in your writing. What motivates you to write about a specific moment in particular?

I suppose elevating the mundane is one way of putting it. I’ve always been taught that small moments are powerful in writing, so I guess I do try to focus on moments in detail just because I think that’s what good writing does… A specific moment in real life can be a trigger, and I find once I start to unpack it in writing, a lot of symbolism and meaning can fall out of it, so unpacking a moment works for me. I think there’s only a couple of poems that play with astronomical imagery. I guess it’s the bigness of the universe that I draw on to compare to the small moments that seem big.

Vanessa to Chris: There is a force of nature that lies beneath your poems. How do you think your present surroundings/ being from Aotearoa New Zealand impacts the way you write?

I’m really interested in what you mean by ‘force of nature’. Do you mean they seem powerful in some way? If so, thanks for the compliment! Is that a mood / atmosphere thing? A mate of mine, Erik Kennedy, said that he thought I was good at creating moods, so maybe that’s what you mean. Is there a particular poem that you think is a good example of that? I take the stance that writing is just words, rather than being in any way connected to, like, my spiritual essence or something. Once the words come out, I’m quite detached from them in the editing process; I just want to make them ‘work’ as a piece of writing, and sometimes that involves ‘deleting’ those lines and phrases that I may feel the most connected to – you’ve got to be a bit detached from the ‘forces of nature’ if you’re going to ‘kill your babies’ so to speak. IDK whether that’s what you meant, though.

I have definitely tried to write poems about being from Aotearoa, but I don’t think any of them have been good enough to be published! I think that most of the poetry I read comes from NZ poets; I like to keep up to date with the contemporary journals, and of course there may be some features of language that happen subconsciously in my poems that are just because I’m ‘a New Zealander’, but putting ‘New Zealandness’ into my poems is not something that is ever at the forefront of my mind when I sit down to write.

Vanessa to Ben: Your writing is so beautiful! What is the place of food in your poetry?

Food is a sensory experience, the transition from material, to the tongue, to chemicals in the brain, to emotion is mind-blowing to me. It epitomises everything that is extraordinary and mystical about the experience of living one single life.

Food also forms the cornerstone of a culture. Generally, we can trace a handful of key ingredients in every culture. Defining culture through one ingredient is fascinating to me. It’s challenging but interesting!

Vanessa to Ben: Your writing spans several languages through words and phrases – from English to Japanese to te reo Māori. What is interesting to you, or important, about using the phrases of the original languages (without necessarily prefacing or explaining them)?

Interesting question. I think it is a lot about the phonetic beauty of language and how they interact with English when placed alongside each other. As poets, we explore meaning, but the phonetic composition is equally as important, drawing from other languages broadens the palette. I have also drawn on quotes, which allows me to go directly to the source, or the essence of the person who uttered them.

Vanessa to Ben: Writing from the perspective of being a Māori person living in Japan feels both curious and insightful, a place to discover both foreign and common cultural connections anew. Which poem were you most surprised by, in terms of what you wrote or gained insight around?

I have always been drawn into Maori culture, but it has never really accepted me. I am of mixed ethnicity and that has always created huge tension in me. I’m not sure any poet truly accepts themselves! I think ‘The Japanese Moko’ was my boldest attempt to blend. The poem/vessel is so short/small, but I feel that I was able to get both Japanese and Maori words/images to snuggle into each other comfortably. I think that the title ‘The Japanese Moko’ is very risky, but I was happy to put it out there.

The poets

Ben Kemp works as a primary school teacher in Papua New Guinea where he has lived for the past three years with his diplomat wife and three children. Gisborne-born Kemp arrived in the Pacific following six years in Australia and ten years in Japan. Tokyo was where he discovered his passion for Kabuki theatre and Japanese film and literature. Between 2003 and 2010 he recorded three studio albums with his band Uminari and toured in Japan, Australia and New Zealand. His artistic work has often explored the nexus between Japanese and Māori/Polynesian culture. He credits the late Taupo-based Māori writer and mentor Rowley Habib with helping him tap into poetry and original writing in his twenties.

Vanessa Crofskey (born in 1996) is a writer and artist of Hokkien Chinese and Pākehā descent. She graduated from Auckland University of Technology with a degree in Sculpture in 2017. Through her practice she investigates social connection: how we form identities through intimacy, inheritance, location and violence. Vanessa has published and presented widely as an interdisciplinary artist – in performance spaces, galleries, festivals plus digital and print publications. She has written for The Spinoff, Gloria Books, New Zealand Herald, Dear Journal, Hainamana and other serious publishing places. She is also a two-time poetry slam champion and award-winning theatre maker but we promise that doesn’t detract from the rest of her career and personality. Vanessa currently works for The Pantograph Punch as a staff writer, and as a curator at Window Gallery (University of Auckland). She advocates for complex trauma survivors and those with attention deficit disorder, plus is very funny and knows a lot about what snacks to eat.

Chris Stewart was born in Wellington but grew up in Christchurch. He has a BA in History and Art History with minors in English and Education from the University of Otago and two graduate diplomas in teaching. After completing the course at the Hagley Writers’ Institute in 2015, winning The Margaret Mahy Prize, his poems have been published in New Zealand journals such as Snorkel, Takahē, Sweet Mammalian, Brief, Catalyst, Mimicry, Blackmail Press, and Aotearotica. He regularly attends the monthly open mic event ‘Catalyst’, a forum for literary and performance poets in Christchurch. Most importantly, he is a son, a brother, a husband, and a father.

AUP page

Thanks everyone – do mark this book on your list to buy once bookshops are back in business. I am raising my glass and declaring this beautiful book well and truly launched.

Kia kaha

Keep well

Keep imagining

Pingback: Poetry Shelf review: AUP New Poets 6 | NZ Poetry Shelf