If you were to map your poetry reading history, what books would act as key co-ordinates?

I couldn’t read as a child. I didn’t read a book till I was 20. My father read me all sorts of crazy stuff. However, I did read poetry. Because it was short and the sounds were wonderful. I read Keats and Shakespeare and the war poets very young, maybe around ten. It’s slow music, really, poetry. I had no idea what many of the words meant. I liked the beat, the rhythms and the small stories of those poems. I remember carrying little poetry books around everywhere, like they held some secret. And they did!

Around that time my mother sent me to an old woman in Avondale for elocution lessons. My mother thought I was swearing too much! ‘Ain’t’ and ‘not never’ etc. Old Mrs Davy was paid to ‘straighten me out.’ Huh! What she did was teach me the beauty of reading poetry, aloud. She made The Highwayman provocative and wild and fun!

C.K. Stead and Allen Curnow were milestones too, because they read to me at university, and made poetry go beyond the page into a life. And Riemke Ensing because she was wildly passionate, and she unpicked poetry like my father ate flounder; sucking the juice around every small bone.

Later I found a seductive freedom in the voice of Hone Tuwhare’s No Ordinary Sun – in Jenny Bornholdt and Paul Muldoon, and Simon Armitage’s Seeing Stars. Check out his poem, Song – perfect beauty.

What do you want your poems to do?

I guess I write to see and hear more about the world I’m in, to be surprised and bear witness to its wonders. I want these poems to be true to their geography, and their people.

When I wrote Walking to Africa, I wanted the poems to stand tall and be loud, and tell the world that adolescent depression is Shit!

In this Large Ocean Islands sequence I want the poems to go beyond the cliché of Pacific Islands, beyond the beachside resorts, to their stronger, truer and older heart.

Which poem in your selection particularly falls into place. Why?

For me each poem is loaded with the story of its writing, and the wider events that surround it. ‘Large Ocean Islands’ is part of a bigger work in progress, and I’m still being challenged to balance the whole, and to give each poem its place and an integrity of its own too.

‘The White Chairs’ is the ‘oldest’ poem of the sequence. You could say it belongs.

UNDRESSING THE LIVES OF THE SILENT HEROES

ADORNED IN SPECTACULAR SUNLIGHT

In reply to C K Wright’s The Obscure Lives of Poets; Revelation lives on a large ocean island

Three serve time in New Zealand. Two in fruit canneries

where golden peaches become the names of their children; Queenie

and Bonnie, who is really Bonanza. One mama brings a nectarine

stone through airport customs in her underwear. Another time,

between two breasts of Kentucky Fried Chicken. Neither flourish.

One thousand roosters with insomnia. One survives the storm that takes

his only son, spends his days in view of the sea, much of it riding.

The sound of one mango falling. Three named after the fathers

of the fathers of monolingual seafarers who came ashore, and left

behind narrow eyes and a new mode of cranial wiring. One of ten

is taken and becomes one of fifteen, unrelated; family ties mapped

back to uplift and shift and fire. One too many three legged dogs.

One joins the police because he believes he can take his dog to work.

One walks around Avatiu harbour at night looking for stars

that have slipped their leash, fallen into the sea. He will be there

to rescue them. One family, the size of fifteen islands connected

by ocean currents. One dances in the lagoon, waist high

in blue, and bouncing for the effect it could have on his waistline,

but only after sunset, and only on the neap tide. One big family.

One maintenance man is sent to prison for acquiring money

that did not belong to him. He has a penchant for high

performance running shoes and real diamonds.

One teaspoon of pawpaw seeds alleviates diarrhoea, and maybe hook worm.

One hands a machete to his son, says just get on with it boy,

not meaning the taro patch or the elephant grass or the palm fronds

hanging over the windows, pulling a blackness over his house.

One Ian George painting is not enough; one stone turtle on the rough grass.

One stays on even after his wife and kids leave, sleeps on a mat

on a friend’s deck, till the mosquitos find him, and immigration says

there is a fine for that sort of behaviour. One wave after one wave.

One island is all one needs to join the dots. One small paradise

emerges in the path of the old navigator, and sets the scene

for growing silent heroes in spectacular sunlight.

There is no blueprint for writing poems. What might act as a poem trigger for you?

I remember Jenny Bornholdt saying how a poem’s form finds itself in the writing, and I think that’s true. In Cyclone Season, the unrelenting heat and the way it lingers for weeks here, triggered a list of observations, repetitive and often banal.

Every day I write ‘stuff’ on my phone. Anything. Sometimes I’m amazed how something so ordinary here is spectacular, and starts a chain of surprise and insight. Like seeing a man at the lagoon at dusk with two small turtles in a tub of water. Watching him later taking them out swimming with him, like they were his children.

Poems are like vehicles; they have doors and windows, and they take you places.

Listening and watching, closely, ruminating, tasting, breathing them in – and sometimes being courageous – that triggers poetry.

If you were reviewing your entry poems, what three words would characterise their allure?

I’m not sure I am seeking to be ‘alluring’ in the poems I write.

In Large Ocean Islands I’d like the reader to see the wonder of the Cook Islands, and honour it. Each small island is big, and delicate and vibrant, and heavy with old wisdom. Sometimes I get a glimpse of something here that is so far removed from where I come from it feels like I’ve moved in time to what ‘we’ were before consumerism and capitalism and industrial economies. There’s a deep truth and a beauty here, that’s both joyous and heart-breaking.

You are going to read together at the Auckland Writers Festival. If you could pick a dream team of poets to read – who would we see?

Seamus Heaney, Robin Hyde, Yehuda Amichai Hone Tuwhare … OK, not a ‘real’ dream then? So many great poets to choose from! Let’s go with… Selina Tusiatala Marsh, Chris Tse, Tusiata Avia, Glenn Colquhoun …

Jessica Le Bas has published two collections of poetry, incognito (AUP, 2007) and Walking to Africa (Auckland University Press, 2009), and a novel for children, Staying Home (Penguin, 2010). She currently lives in Rarotonga, where she works in schools throughout the Cook Islands to promote and support writing.

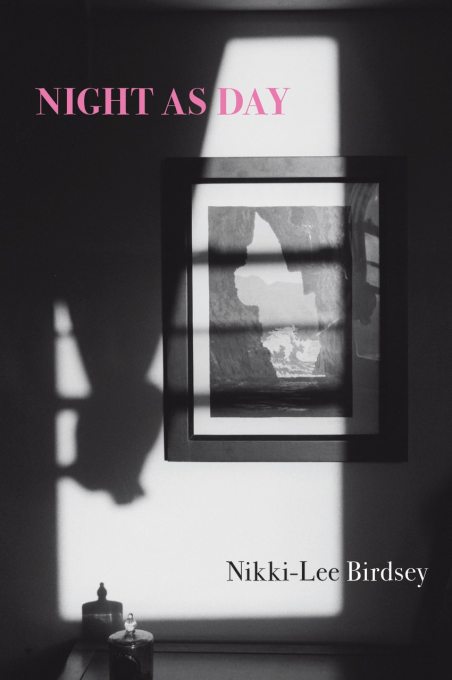

Nikki-Lee Birdsey, ‘Foreign and Domestic’, from Night and Day, Victoria University Press, 2019

Nikki-Lee Birdsey was born in Piha. She holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a BA from New York University. Her poems have been published in various journals in New Zealand and internationally, including The Iowa Review, Fence, LIT, The Volta, Sport and Hazlitt. In 2015 she was a visiting faculty fellow at the International Institute of Modern Letters at Victoria University of Wellington, where she is currently a PhD candidate. Her first book, Night as Day, was published by Victoria University Press in April 2019.

Victoria University Press author page

Prominent Samoan writer honoured by Victoria University of Wellington

Samoan writer and academic Letuimanu’asina Dr Emma Kruse Va’ai will receive an honorary doctorate from Victoria University of Wellington at a graduation ceremony this month.

Letuimanu’asina grew up in Samoa and came to study at Victoria University of Wellington on a New Zealand Aid scholarship, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in English Literature and a Diploma in Teaching English as a Second Language. She went on to complete a doctorate in English at the University of New South Wales, after joining the National University of Samoa in 1987 as a lecturer in English, rising to become a professor in English and applied linguistics. Her long service at the National University of Samoa culminated in her appointment as Deputy Vice-Chancellor. Currently she is chief executive of the Samoa Qualifications Authority.

Alongside her academic career, Letuimanu’asina has established herself as one of Samoa’s leading poets and writers of short stories. Her writing is notable for its blending of the Samoan and English languages, which echoes her academic interest in bilingualism in Samoa and the connections between language use and cultural identity.

The University’s Chancellor Neil Paviour-Smith says the honorary degree of Doctor of Literature acknowledges Letuimanu’asina’s commitment to developing a bilingual Samoan–English education system, as well as her impressive body of work as a poet and author.

“Letuimanu’asina is an outstanding example of the type of graduate we aim to produce at Victoria University of Wellington. Both her creative and academic writing are grounded in a deep commitment to her society, and her academic leadership and service has done much to support Samoan students eager to further their education in Samoa and overseas,” Mr Paviour-Smith says.

Letuimanu’asina has served on a number of boards responsible for education and development at the Commonwealth, Pacific, and Samoan levels. She has always been a strong advocate for Pacific women graduates, and is a former president of the Samoa Association of Women Graduates and a founding member of the Pacific Graduate Women’s Network. In 2006, then Prime Minister Helen Clark presented her with a Prime Minister’s Award for Emerging Pacific Leaders in recognition of her commitment to initiating and supporting educational projects to help young women in education. The award enabled her to study at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

“Letuimanu’asina’s leadership and desire to serve others have been an inspiration to many across the Pacific, and make her a fitting recipient of this honorary doctorate,” Mr Paviour-Smith says.

The Victoria University of Wellington Council will confer an honorary doctorate on Letuimanu’asina Dr Emma Kruse Va’ai at a graduation ceremony on Thursday 16 May.

The Starlings

Anger sang in that house until the scrim walls thrummed.

The clamour rang the window panes, dizzying up chimneys.

Get on, get on, the wide rooms cried, until it seemed our unease

as we passed on the stairs or chewed our meals in dimmed

light were all an attending to that voice. And so we got on,

and to muffle that sound we gibbed and plastered, built

shelves for all our good books. What we sometimes felt

is hard to say. We replaced what we thought was rotten.

I remember the starlings, the pair that returned to that gap

above the purple hydrangeas, between weatherboard and eaves.

The same birds, we thought, not knowing how long a starling lives.

For twenty years they came and went, flit and pause and up

into that hidden place. A dry rustle at night, fidgeting, calling,

a murmuration: bird business. The vastness and splendour

of their piecemeal activity, their lives’ long labour,

we discovered at last; blinking, in the murk of the ceiling,

at that whole cavernous space filled, stuffed like a haybarn.

It was like gold, except it was more like shit and straw,

jumbled with their own young, dead, desiccated, sinew

and bone, fledgling and newborn. Starlings only learn

a little thing, made big from not knowing when to leave off:

gone past all need except need, enough never enough.

Tim Upperton

from A House on Fire, Steele Roberts, 2009

Sarah Jane Barnett:

Since I first read Tim’s poem, it’s been my favourite by an Aotearoa writer. When I was a kid living in Christchurch, a hive of bees lodged themselves in our bathroom’s exterior wall. We could see them go in and out through a tiny hole in the stucco concrete. They’d land, pause for a moment on the hole’s lip, and disappear into the hollow. Eventually my parents had them fumigated.

There is so much to admire in Tim’s poem – the vibrating yet unpretentious language; the gentle comparison he creates between the labour of the family who ‘gibbed and plastered’ and the labour of the starlings’ ‘bird business’; his use of the collective noun, ‘murmuration’. I recommend listening to Tim read the poem to really see how good it is.

For me, the emotion of the poem comes from the family trying to ‘muffle’ the starlings. It makes me think about growing up in a house where ‘anger sang’ but was never acknowledged, and the way a child will push their fear and feelings down by concentrating on something else: starlings for example, or bees.

Sarah Jane Barnett is a freelance writer and editor. Her poetry, essays, interviews and reviews have been published in numerous journals and anthologies in Aotearoa and internationally. She has two poetry collections: A Man Runs into a Woman (finalist in the 2013 New Zealand Post Book Awards) and WORK (2015). Her poems often inhabit the lives of others, and ask how we find connection and intimacy when affected by trauma. Her essays explore the multifaceted theme of modern womanhood. Find out more here.

Tim Upperton’s second poetry collection, The Night We Ate The Baby, was an Ockham New Zealand Book Awards finalist in 2016. He won the Caselberg International Poetry Competition in 2012 and again in 2013. His poems have been published widely in New Zealand and overseas, and are anthologised in The Best of Best New Zealand Poems (2011), Villanelles (2012), Essential New Zealand Poems (2014), Obsession: Sestinas in the Twenty-First Century (2014), and Bonsai (2018).

The sixth annual WriteNow poetry competition for Dunedin secondary school students is now open for entries.

This year’s judge is Fiona Farrell.

Entries close at 5pm on Friday 26 July 2019. See how to enter here.

Results will be released on Monday 19 August 2019 (on this website)

All the details, plus previous years’ judges’ reports and winning poems, are available on the WriteNow website

The judge for the 2019 WriteNow poetry competition is Fiona Farrell. Fiona is one of New Zealand’s most acclaimed and versatile writers. She is an award-winning poet, novelist, short story writer and essayist. In 2007 she was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Fiction, and she held the 2011 Robert Burns Fellowship at the University of Otago. Recently she edited the 2018 edition of Best New Zealand Poems.

The judge for the 2019 WriteNow poetry competition is Fiona Farrell. Fiona is one of New Zealand’s most acclaimed and versatile writers. She is an award-winning poet, novelist, short story writer and essayist. In 2007 she was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Fiction, and she held the 2011 Robert Burns Fellowship at the University of Otago. Recently she edited the 2018 edition of Best New Zealand Poems.

You can read more about Fiona Farrell on her website here.

Photo Credit: Sophie Davidson

If you were to map your poetry reading history, what books would act as key co-ordinates?

My poetry reading history – by which I mean paying attention to poetry and seeking it out on my own terms – begins with Anne Carson, whose long poem “The Glass Essay” was introduced to me by Anna Jackson in my final undergraduate year of uni. Her translations of Sappho in If Not, Winter and her shadowy, hybrid work Nox suddenly split open for me the limits of what poetry could mean. That’s when I began to feel at home in poetry, maybe because I’ve always been drawn to things that can’t be explained.

Very quickly in my literature degree I realised that the ‘Western literary canon’ we studied was the product of a violent colonial legacy. Instead I felt a pull towards the fringes of contemporary poetry, where I found poets doing extraordinary things with poetic form and linguistic boundaries, especially in The Time of the Giants by Anne Kennedy, The Same as Yes by Joan Fleming, and Lost And Gone Away by Lynn Jenner.

But it wasn’t until I discovered Cup by Alison Wong during my MA year that I recognised something of my own childhood and background in New Zealand poetry. Loop of Jade by Sarah Howe, published in 2016, was the first poetry book I ever read by someone half-Chinese like me. Ever since, I’ve been building my own poetry canon made up of works that negotiate displacement, loss, diaspora, living between cultures, and the ongoing damage caused by European colonisation. Schizophrene by Bhanu Kapil, Citizen by Claudia Rankine, Whereas by Layli Long Soldier, and Poukahangatus by Tayi Tibble are all books that I would like to carry around me at all times like talismans to keep me safe.

What do you want your poems to do?

I want a poems that are spells for curing homesickness, I want poems that are notebooks and witness accounts and dream diaries, I want poems that create a noticeable shift in the temperature of the air and transport you to your grandma’s kitchen.

Which poem in your selection particularly falls into place. Why?

I knew that when I saw a kōwhai tree in full bloom in a garden in north London, close to where I was working at the time, I would need to write about it because it was the only thing I could do. It was spring and in spring I tend to feel really melodramatic about things. I don’t think the poem is melodramatic, though; I think it ended up somehow capturing what I was feeling, in fragments: both very far away and very close to home at exactly the same moment.

There is no blueprint for writing poems. What might act as a poem trigger for you?

Recent poem triggers: silken tofu, being near the sea, tracking sunlight across my tiny garden in order to figure out where particular plants will grow, a house on fire by the side of the motorway, chocolate ice cream, dreams about whales, Chinese supermarkets, reading, reading.

If you were reviewing your entry poems, what three words would characterise their allure?

(This is too difficult and I wish I could ask someone else). Dreamlike, downpour, heatwave.

You are going to read together at the Auckland Writers Festival. If you could pick a dream team of poets to read – who would we see?

It would have to be a few American and British poets who I’ve discovered only since moving to London, because I want them and their work to travel as widely as possible. But I wouldn’t want to read alongside them because then I would be too nervous / too in awe / tearful to listen properly. Ocean Vuong – because sometimes at poetry readings he bursts into song. Also Tracy K. Smith, Raymond Antrobus, Bhanu Kapil, and Rachel Long.

Nina Mingya Powles is of Pākehā and Malaysian-Chinese heritage and was born in Wellington. She is the author of field notes on a downpour (2018), Luminescent (2017) and Girls of the Drift (2014). She is poetry editor of The Shanghai Literary Review and founding editor of Bitter Melon 苦瓜, a new poetry press. Her prose debut, a food memoir, will be published by The Emma Press in 2019.

You can hear Nina read ‘Mid-Autumn Moon Festival 2016’ here

Owen Leeming, Through Your Eyes: Poems Early and Late Cold Hub Press, 2019

Owen Leeming has a fascinating bio on the back of his new poetry collection: he was a radio announcer, briefly studied musical composition in Paris, lived in London, published his poetry in various English magazines, became a UNESCO expert in Africa, settled in Provence, was the first writer to receive the Katherine Mansfield Menton fellowship (1972), joined Club Med in Spain where he met his future wife, worked as a translator for the OECD in Paris. He has remained based in France. His debut poetry collection, Venus is Setting, was published by Caxton Press in 1972.

This new collection is in debt to a trip back to New Zealand with his wife, Mireille but also assembles earlier poems from previous visits home. David Howard endorses the book, likening it to a vessel with two masts (the poems ‘Sirens’ and ‘Khalwat’) that set sail from Owen’s classic poem ‘The Priests of Serrabonne’. That poem was first published in Landfall in 1962.

Owen travels across four decades worth of fascinations, anchors and connections to place, people and ideas. The poems offer deft musical keys, lapping and lilting like little oceans, an undulation of consonants and vowels, assonance and rhyme. The sequence of physical returns form an elastic stretch between homes – France and Aotearoa. The poems often act as surrogate translations as though Own is translating his country of birth for Mirielle but also, and equally importantly, for himself transplanted at a distance. As he says in the terrific opening poem, ‘Crossing the Tasman’: ‘A sea still flows and Morse / messages stutter from a place you still call home.’

In a book that offers a measured pace, an attentive ear and evocative images, the opening poem is my favourite poem:

Bracing yourself against your life, you gaze

across ten years’ chop and swell:

That water widens still from then to now,

from home to now—(but where is home?)—sprays

on bitter wind the rail, your knuckles, eyebrow

and eye, pouring between your past (…)

Ruth Hanover, Other Cold Hub Press, 2019

Ruth Hanover, with a degree in English and a background teaching ESOL to refugees in Cairo, Stockholm and New Zealand has published a collection born of this experience, along with the experience of travel and years in therapy. Her poems have been published in London Grip, a fine line, takahē, Poetry New Zealand and Manifesto Aotearoa: 101 Political Poems (Otago University Press). Her poem, ‘The Tent’ gained the Takahē Poetry Prize 2017 and a new work was longlisted in the Peter Porter Prize in 2019.

To be reading the collection in the wake of the Christchurch terrorist attacks is to be acutely aware of certain issues. What do we mean when we say ‘we’ or ‘us’ or ‘them’, for example? To what degree should we voice the lives, pains, joys of others? Ruth’s book is dedicated to ‘the seekers of asylum and for those who reach towards them’. It is a timely arrival as we grapple with tragedy and how to reach out and indeed how to speak.

Ruth’s poems are not a matter of speaking on behalf of but a speaking towards, a speaking out of imagining, placing light on dislocations, violences, deprivations, catastrophes, inhumanity. They poems are written along a pared back line, with exquisite economy, as a sequence of voices, other voices – perhaps imagined and perhaps experienced – speaking from real situations.

I had gone in for oranges early persimmon —

the lush fruit the abundance. Behind me

‘but Europe — the réfugees did-you-see?

‘They were everywhere

The reply. The tone. I turn unstable

unable to bear the weight

of the oranges drop them drop

them in among the persimmon feel —

complicit as if I had committed

some act. (…)

from ‘The oranges’

We move from Nauru to Syria to Paris to Stockholm. We move with refugees, with the displaced and, as I move as reader, I feel other. Moved yet motionless in my state of privilege. I feel the helpless slap of what I can do in the face of intolerance.

Poetry can be the occasion of listening; Ruth offers subtle melodies in her finely crafted poems but she also offers other points of view. Both melody and viewpoint employ gaps on the line, fragments, with punctuation adrift to underline the difficulty of speaking of catastrophe. With an alluring blend of grace and sharpness, ease and discomfort, I can’t wait to see what else Ruth writes.

Victoria Broome, How We Talk to Each Other, Cold Hub Press, 2019

We are quite separate in this big house. Nana is a

good cook but she doesn’t hug, it’s hard to know

what makes us such companions. I think there are

things we know about each other we don’t know.

A bit like the mysterious chemistry of placing

flour and butter and eggs and sugar into a bowl

and then an oven and then a plate and then a mouth.

from ‘Nana in the Upstairs Bedroom’

Victoria Broome has published poems in literary journals and anthologies, was awarded the CNZ Louis Johnson Bursary (2005) and has twice been placed in the Kathleen Grattan Award (2010, 2015). How We Talk to Each Other is her debut collection.

The poems in How We Talk to Each Other arc over ten years, drawing upon familial experience, particularly memories of her parents, hooking the luminous detail that has endured. Poetry becomes a family imprint and like Ruth, Victoria pares back a scene until it shines. Big events are viewed on the fringes; how the young child witness feels, what she does, the glinting physical detail.

Victoria’s collection shows so beautifully the power of domestic poetry – poems that connect at the level of family – to slip under your skin and stay.

Sunnyside

Grandad went to the Mental Hospital

when we were in Wellington, he made us

sheep’s wool slippers, mine were royal blue

they came in a brown parcel in the post.

Then on a Sunday Mum got a phone call.

I heard her cry, ‘Oh no, oh no.’

At first she said, ‘He had a heart attack.’ The Dad said, ‘No,

he killed himself in the garage, he drank some poison.’

I aw the Irish Peach tree by itself at the back of the long yard.

Mum flew down and cleaned out the house. Nana came to stay.

I wore Mum’s rage, she chased me round and round the house

screaming while Nana stood with her hands up to her face.

Some nights I went riding on the train in the dark lit up by the yellow

light of the carriages, past the harbour to the city and then back again.

I stopped when Dad said I’d be made a ward of the state.

This book filled me with a warm glow – yes poetry can do anything and can affect us in so many vital ways, including the discomfort I felt reading Other – but on some occasions the deft translation of life, of everyday goings on, the view out the window, the family behaviours along with the losses, the absences, the deaths – produces poetry that is like a gold nugget. I need this. It restores me, it nourishes me, it reminds me that in poem empathy we witness humanity.

Owen Leeming Cold Hub Press author page

Ruth Hanover Cold Hub Press author page

Victoria Broome Cold Hub Press author page

Vaughan Rapatahana presents Part 2 of his feature on New Zealand Asian women poets. He considers rage and alienation but stresses these women write so much more. The poets: Aiwa Pooamorn, Nina Powles, Vanessa Crofskey, Wen-Juenn Lee, Shasha Ali and Joanna Li .

You can read the full piece with poems here.

On Poetry Shelf:

You can read Vanessa’s poem ‘The Capital of My Mother’ here

You can hear Wen-Juenn read ‘Prologue’ here

You can hear Nina read ‘Mid-Autumn Moon Festival 2016’ here