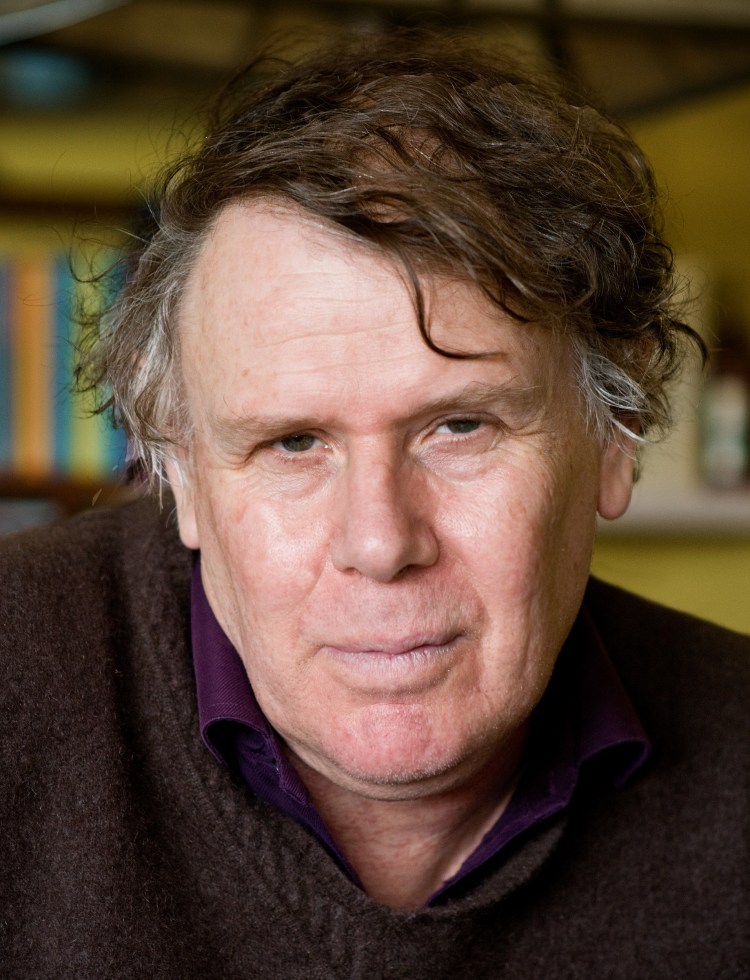

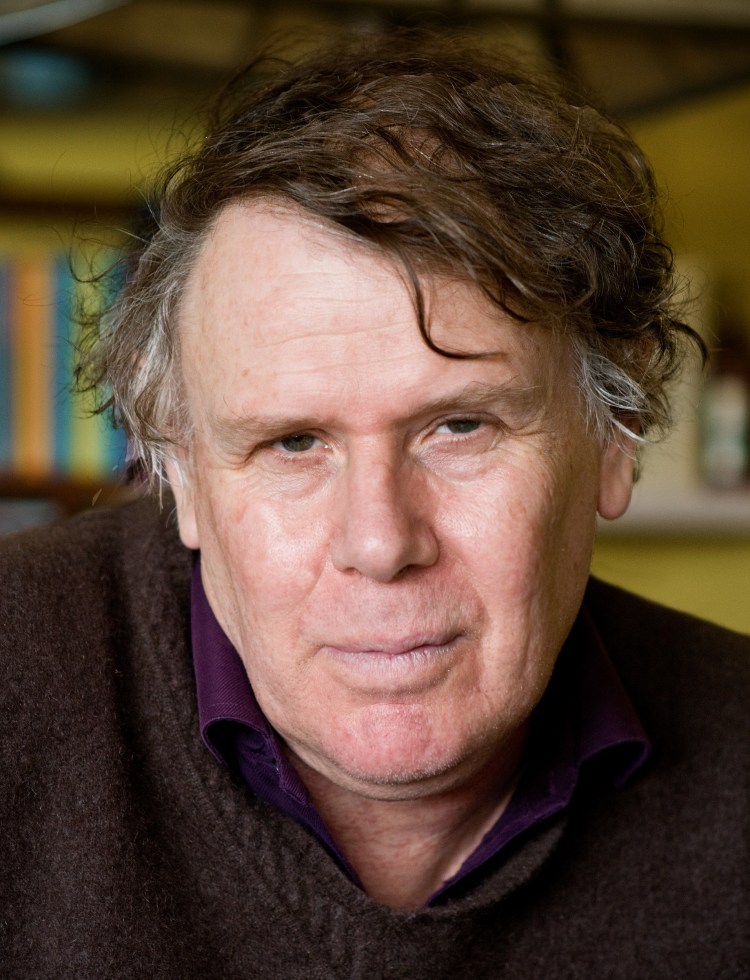

Photo credit: Robert Cross

Harry Ricketts teaches English literature and creative writing at Victoria University. His thirty plus books include poetry, literary biographies and essays. His biography, Strange Meetings: The Poets of the Great War, is a terrific example of how nonfiction can depend upon heart and intellect, deep scholarship and personal engagements. The war poets are illuminated with fresh insight, emphasis and connections. Harry’s latest poetry collection, Winter Eyes, relishes the power of language to do many things: to lay down musical chords, prismatic subject matter, personal revelations. The poems made me grin wryly, stop and reread, and on occasion weep. It was with great pleasure we embarked upon an unfolding email conversation.

Harry Ricketts, Winter Eyes

Victoria University Press, 2018

Talking about poetry

iv

The song strokes the past

like a boa, like some fur muff

or woollen shawl

but the past is not soft at all;

it’s rough to the touch

sharp as broken glass.

from ‘Song’

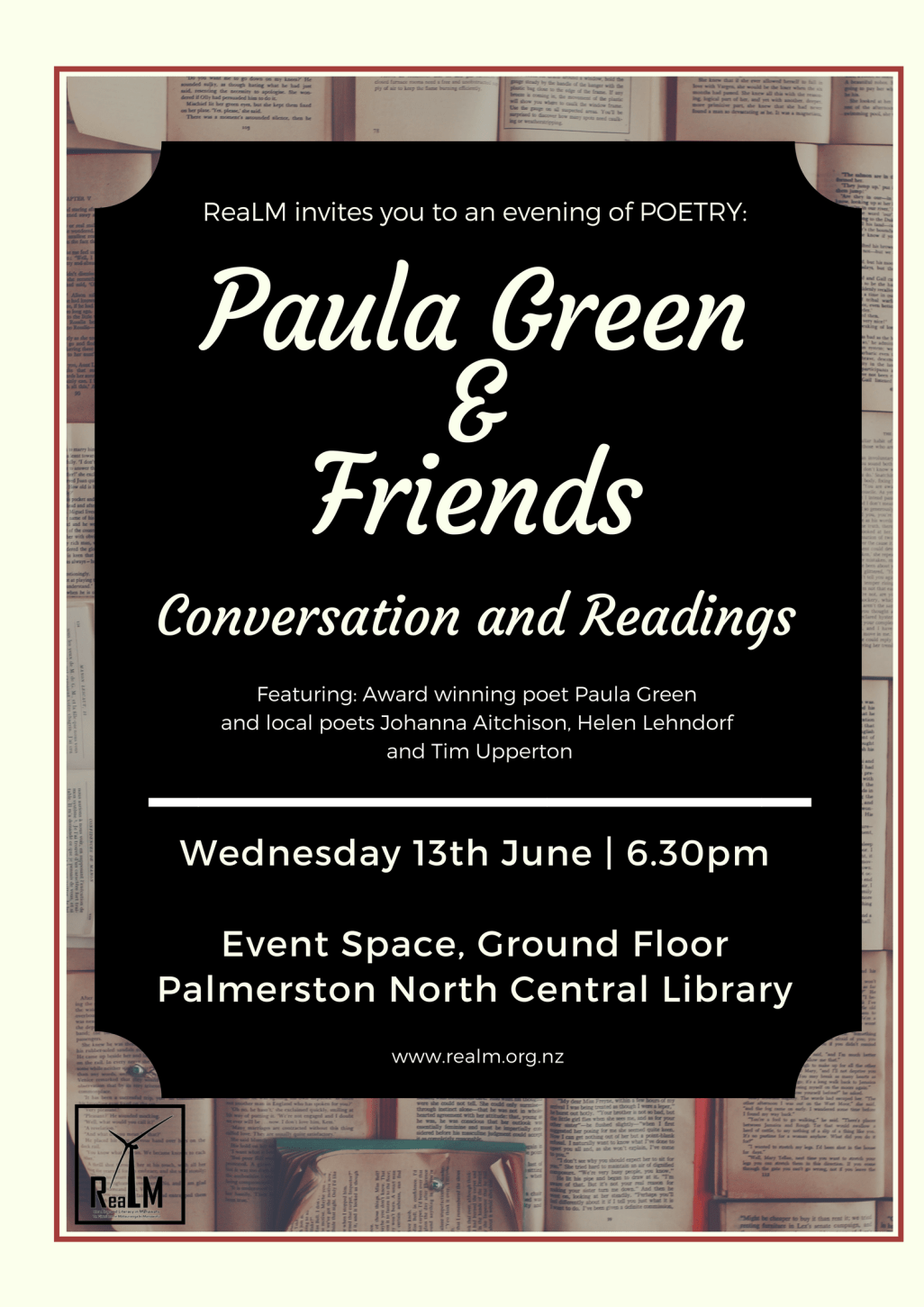

Paula: The first poem, ‘Song’, is the perfect entry into your new collection. The poem, songlike and exquisitely paced, turns in multiple directions. It favours the external alongside the interior, the strange alongside the everyday. Do you see this new book as a stretching out?

Harry: Yes I do in some instances. I certainly hadn’t written anything like ‘Song’ before. It was a poem which seemed to sing itself rather than having to be fetched. Quite often phrases or lines will come to me, and I’ll jot them down and come back to them and see if they’ll catch fire. I’ll usually do several drafts, fiddling around, chopping and changing, finding new possibilities. That wasn’t the case with ‘Song’. I wrote the first few sections all in one go; then later added a bit more, and it seemed to know when to end. A few of the other poems happened like that, too. I’m not sure the emotional topography is all that different, though.

She bites at the cheese scone

I’ve buttered and quartered, chews

slowly. ‘Yesterday,’ she begins,

‘it was whurr-whurr-whurr.’ Stops.

‘It was,’ I say. ‘But today

it’s calm and bright.’ ‘Yes,’ she agrees

from ‘Picnic’

Paula: The emotional topography is contoured and that is one of the reading pleasures. In fact some of the poems are acute emotional hits even though the strata of feeling is subtle. I am thinking of ‘Picnic’ and the mother observations that are restrained and tender. Or the word play in ‘Margravine Cemetery, Barons Court’ that almost becomes a haunting. To what degree are you putting yourself in the poems as opposed to a composite speaker?

Harry: I am mostly putting myself into the poems, or bits of myself anyway; they are all personal to varying degrees, even confessional, though I know for some people that’s become a degraded term. The ‘mother’ poems are about my own mother in a direct, if slivery, way. I suppose I’m trying to maintain one side of a conversation with her now that she can’t complete sentences any more. In a different way, I think that’s also true of the sequence about my late stepson. But in other poems a kind of transformation does seem to have occurred, and the speaker both is and isn’t me. I think that’s true of ‘Song’, ‘Margravine Cemetery’, ‘Fields of Remembrance’ and some of the triolets and tritinas. ‘S. 1974’, on the other hand, is straight ventriloquism.

This grave is a-tilt

As though the earth moved:

Agnes. Something. Faithful …

Red and yellow leaves steering down

The soft October afternoon.

from ‘Margavine Cemetery, Barons Court’

Paula: The mother poems work so beautifully, and I now realise why I felt like I was eavesdropping on intimate moments. I think the personal movement – this shifting from confession to shards to grey areas to ventriloquism – is what heightens the multi-toned effect of reading. Nothing feels like an exercise. There are the diverse currents of feeling but there are also the eclectic conversations. Could you see this as a collection of conversations that stretch out to place, family, incident, other writers?

Cape daisies mauve the hills, give me a spring

to the spirit my mother beside me will not hold

onto, any more than the rhododendron’s pink –

‘Oh lovely!’ She too was once in the pink,

a student in the black-out, and it’s spring,

and she’s in love’s stranglehold

from ‘Spring’

Harry: Yes, I agree, though I hadn’t quite seen the collection like that till you pointed it out. I think poems are forms of conversation with others, real and imagined, often conversations one would like to have had. Years ago, a friend and I used to play what we called The Dylan Game. We imagined ourselves in a railway carriage, empty except for us. The train stops at a station. Into our compartment steps Bob Dylan. There is no corridor; the next stop is twenty minutes away. What will we say to him and he to us? The game went on for some months till we realised we’d be so nervous and star-struck, we wouldn’t be able to say a word. Among the many other things poetry can do, it can fill some of that gap, with family, friends, other writers, fictional characters, the living, the dead. Those kinds of conversations have been an aspect of your poetry, too, haven’t they?

Paula: Yes, and I haven’t quite thought of it like that either. All those people that stalk through my poems! I like the idea of poetry inhabiting a gap, furnishing a gap almost – writing the gap. I am also struck how you stretch form in this collection. The ‘Grief Limericks’ are a case in point. Steve Braunias published these on The Spin Off and it has had a near record number of views. How did the tight rhyming form work for such tough subject matter? Are there other examples that you feel transcend form as exercise and catch something extra?

I once had a stepson called Max,

liked Gunn and Blood on the Tracks.

But things were askew,

were tangled in blue.

I once had a stepson called Max.

from ‘Grief Limericks’

Harry: The constraints of any reasonably tight poetic form can sometimes actually be a help in writing poems involving strong and difficult feelings. John Donne has a couplet: “Grief brought to numbers cannot be so fierce, / For he tames it, that fetters it in verse”, though I’m not convinced about the ‘taming’ exactly. ‘Grief Limericks’ is part of a sequence of elegies for my late stepson Max. As I say in the Notes at the back of the collection, I got the cue from Nick Ascroft’s ‘Five Limericks on Grief’ in his recent collection Back with the Human Condition, though I follow Edward Lear’s original format in which line one is repeated as line five. It’s the clash of the form’s comic associations and inexorable patterning with such unexpected subject matter. I don’t think of any of the triolets and tritinas in Winter Eyes as ‘exercises’. A few are meant to be playful in a mordant sort of way, but each is also trying to catch some flashing moment, some twist of feeling.

Paula: Yes! Repetition is such a lure; on the one hand it is a thing of comfort, it heightens feeling or relishes playfulness. The glare of the water in ‘Lake Rotoma’ cuts into the daily routine: ‘Mostly we eat, talk, drink and read.’ There is the flashing moment, the twist of feeling.

On the back blurb, poetry is offered as both comfort and confrontation. This works for me as I read through the collection. I don’t think I have seen these two words in partnership in a blurb and they really got me thinking about being both reader and writer. They explain why I love your book so much but also, and this surprised me, tap into my writing life. What do you want as a poetry reader? Did any books particularly stick with you as you wrote Winter Eyes?

Harry: I want many different things as a poetry reader. I want to be pulled into a world. I want to be startled. I want to be shown things. I want the hairs to stand up on the back of my neck. I want to be moved. I want to be amused. (I don’t want to be patronised, bullied or conned.) I dip in and out of a lot of poetry, ancient and modern, local and overseas. I was reading Airini Beautrais’s and Therese Lloyd’s poetry very intently during the two to three years I was writing the poems in Winter’s Eyes, because I was lucky enough to be one of their creative writing PhD supervisors. Their work has certainly stuck, as has Andrew Johnston’s Fits & Starts, Hera Lindsay Bird’s Hera Lindsay Bird, Nick Ascroft’s Back with the Human Condition and Chris Tse’s How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes. But there are various poets who are just part of my mental landscape, and some of them show up in these poems one way or another: W.H. Auden, Philip Larkin, Bill Manhire, Lauris Edmond, Derek Mahon, Wendy Cope, Andrew Marvell, Carol Ann Duffy …. songwriters like Dylan.

This ‘thinly plotted’ pantomime

must always end too soon.

There’ll be time, we say; there’ll be time

to rewrite our part in the pantomime

from “Hump-backed Moon’

Paula: What you want as reader sums up the effects I have had reading Winter Eyes. I was amused by ‘On Not Meeting Auden’, moved by the Max and mother poems, and got goose bumps as I read ‘Song’ and ‘Hump-backed Moon’. This multi-toned book takes you many places. Do you just write for the page? Or do you also write to read aloud?

Out there, all this hot, bright morning

the tūī working the flax,

white bibs bobbing up and down.

In here, it’s cooler and dimmer.

Deep in my English Auden

suddenly in your ghost again.

from ‘Love Again’

Harry: I usually write with the page in mind. I like the visual aspects of poems, the line-breaks, the verse-breaks, using syllabics as an organising principle or skewing a set form, all the possibilities of shaping words and rhythms on the page. The English poet C.H. Sisson, who wrote mostly in free verse, says somewhere that the proof of a poem is in its rhythm, not a fashionable view. I like poems that sing, particularly if it’s a broken song. I do sometimes think while working on a poem that it might go okay aloud or later discover that it seems to. ‘Song’ works all right aloud, I think; but ‘Love Again’, one of the elegies for my stepson, is quite compressed in places and is probably better on the page. It’s hard following a lot of new poems at a reading; it’s easy to lose track; you can’t stop and go back. My ideal poetry reading is where I know most of the poems already and can enjoy listening to how the poet reads them. Of course, some poets are mesmeric readers. Bill Manhire is. Seamus Heaney was.

Paula: Jesse Mulligan interviewed Jane Arthur, the Sarah Broom Poetry Prize winner, last week and got her to read the same poem twice. I thought that was genius. So yes, when you hear Bill read ‘Hotel Emergencies’ or ‘Kevin’ or the Erebus poems after having read or even heard them before, you just feel more enriched. I have to say I really loved your reading at Miaow last year. I could feel the audience around me move forward and listen.

The process of writing a poem is so mysterious. Was there one poem in this collection that took you by surprise?

Harry: Thank you for what you say above. Very generous. Several of the poems took me by surprise. I was in the middle of a university meeting when the opening line of ‘Grief Limericks’ came into my head: “I once had a stepson called Max”. I hadn’t been thinking about him. ‘Good at Languages’, about my friend Nigel, started when I was, as in the poem, walking down the steps to the Von Zedlitz Building where I work. I heard this blackbird and instantly thought of him and the lines he would quote from John Drinkwater’s poem. ‘Napier, Christmas 2017’: we were driving to Napier and suddenly just before we got there way out in a field there was a sign saying “Shock your Mum. Come to Church” in huge letters, and I knew I had to write a poem around it. Actually, I think most of the poems took me by surprise, and I’m grateful they did.

Thank you Harry. It is always a pleasure to talk poetry with you.

Good at languages

(for Nigel, 1950-2008)

You were good at languages,

could play any tune by ear:

“Doesn’t it go something like this?”

you’d say, and so it did. Poetry

wasn’t your thing, but you had two

standbys you could always pull out.

The first you’d remembered

from Alec Annand’s A Level

English class. I was so impressed

the first time you produced it,

early one summer morning in 1970

as you drove us in your Morris Traveller

to the Ribena factory in Coleford

(“Gateway to the South”, you called it).

The pigeons as usual were eating

gravel off the road and clattering up

from under the wheels. And suddenly you came out

with “O sylvan Wye, thou wanderer

through the woods.” And there it was

down there below us, not in a poem,

but real, woody (and silvery), wandering.

This morning as I walk down the steps

from Glasgow St to Von Zedlitz

a blackbird starts to sing. Which was your other

standby (remembered from some other class):

“He comes on chosen evenings

My blackbird bountiful, and sings

Over the garden of the town …”

I can hear you recite the lines

with that slight grin in your voice.

It’s the palest shadow of you,

but for now, actually forever, it will have to do.

©Harry Ricketts 2018

Victoria University Press page

Radio National: Kim Hill and Harry Ricketts interview