Monthly Archives: August 2015

Compounds & Collisions at Q Theatre mixes it up in a creative sampler

We’re showcasing the hidden treasures of Auckland’s creative scene with a curated sampler of artistic delights.

This instalment features poems by Jess Holly Bates and Tourettes, a performance by 2015 Billy T winner Hamish Parkinson, readings by novelist Sue Orr and playwright Josephine Stewart-Tewhiu and Tui-award-winning music by Great North’s Hayden Donnell.

Tickets are $15 and available from Q Theatre. All proceeds go towards paying our wonderful writers.

Compounds and Collisions is part of a trilogy of writerly events. See the others here.

Victoria University Press warmly invites you to the launch of Ocean and Stone by Dinah Hawken

Victoria University Press warmly invites you to the launch of

Ocean and Stone by Dinah Hawken

on Thursday 10 September, 6pm–7.30pm

at Unity Books, 57 Willis St, Wellington.

Ocean and Stone will be launched by Greg O’Brien

$35, paperback, colour drawings by John Edgar

About the book:

Ocean and Stone, Dinah Hawken’s seventh collection of poetry, is a book of many elements.

The central sequence page : stone : leaf, interspersed with the striking drawings of John Edgar, is framed by poems of growing up and growing old. They, in turn, are framed by poems written in the natural world, beside a lake and beside an ocean. At the heart of this book is urgency: the urgency to know the limits of our planet and ourselves, and to live within them.

Ocean and Stone is elemental Dinah Hawken, at once meditative and resolute.

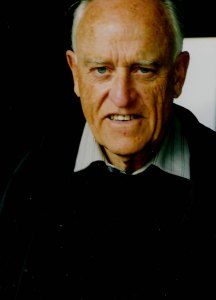

Poetry Shelf congratulates our new Poet Laureate

Photo credit: Marti Friedlander

CK Stead is our new Poet Laureate.

I was in the thick of stand-still, rush-hour traffic on the way to a South Auckland School this morning when I heard the news and it gave me a much needed boost. Poetry has always been a primary love in the broad spectrum of Karl’s work. His poetry catches your attention on so many levels because his poems become a meeting ground for intellect, heart, experience, musicality, craft, acumen, a history of reading and thought, engagement with the world in all its physical, human and temporal manifestations.

I am delighted to celebrate this result.

Here is a snippet from an interview I did with Karl for Poetry Shelf last year:

Your poems are delightfully complex packages that offer countless rewards for the reader—musicality, wit, acute intelligence, lucidity, warmth, intimacy, playfulness, an enviable history of reading, irony, sensual detail, humour, lyricism. What are key things for you when you write a poem?

It has to be a meeting of words and feeling, in which the words are at the very least equal in importance, and the feeling can be of any kind, not just one kind. I like wit, think laughter can be tonic, but of course it doesn’t fit all occasions.

There were a number of significant poets in NZ from the 1940s onwards and you have interacted with many of them (Curnow, Mason, Glover, Baxter and so on). Were there any in particular whose poetry struck a profound chord with you?

Curnow was always the most important for me. But when I was young Fairburn’s lyricism seemed very attractive; Glover at his rare best (the Sing’s Harry poems); Mason likewise (‘Be Swift O sun’); Baxter – especially in his later poems: they have all been important to me.

Do you think your writing has changed over time? I see an increased tenderness, a contemplative backward gaze, moments where you poke fun at and/or revisit the younger ‘Karls,’ a moving and poetic engagement with age, writerly ghosts and death. Yet still there is that love and that keen intelligence that penetrates every line you write.

You are very kind! I certainly feel ‘older and wiser’ in the sense that things don’t matter so much, one accepts the fact of human folly and one’s own share in it. Indignation doesn’t stop, but there is a kind of weary acceptance, and laughter. I still feel embarrassment – especially when looking back – but I recognize that as not only a safeguard against social mistakes, but also as another manifestation of ego, as if one feels one should be exempt from folly.

There have been shifting attitudes to the ‘New Zealand’ label since Curnow started calling for a national identity (he was laying the foundation stones that we then had the privilege to use as we might). Does it make a difference that you are writing in New Zealand? Does a sense of home matter to you?

When I was young I was a literary nationalist. Now I regard nationalism as a form of tribalism and the result of genetic programming no longer suitable or safe in the modern world. So I have changed a lot. But I still recognize regional elements as important, even essential, in the poetic process. I think Curnow himself became more a regional poet and less a nationalist one; but the arguments that had swirled around all that had had the effect of committing him to positions which he didn’t want to resile from, so he remained the committed nationalist, perhaps after the need had passed.

What irks you in poetry? What delights you?

I suppose any kind of excess, of language or of feeling; and solemnity – especially the sense that poetry is taking itself too seriously and asking for special respect.

There are many kinds of delight in poetry, but almost all of them involve economy. If an idea or an experience or a scene or a personality or whatever can be conveyed as well in 10 words as in 20, those 10 words will be full of an energy which the more relaxed and expansive version lacks. They will be radio-active.

Name three NZ poetry books that you have loved.

Singling out living poets might be invidious, but here are three by poets now dead: You will know when you get there (Curnow); Jerusalem Sonnets (Baxter); Pipe Dreams in Ponsonby (David Mitchel).

The full interview here.

Poetry Shelf interviews Fiona Farrell – ‘Fiction seemed a kind of insult, really, to people experiencing such difficult or appalling narratives of fact’

Fiona Farrell is a much loved New Zealand author who writes in a variety of genres (poetry, fiction, non-fiction, mixed genre) and who is unafraid to test the boundaries of heart, intellect and craft whenever and however she writes. She has won awards: The Prime Minister’s Award for Fiction in 2007 and she was made an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for Services to Literature in 2012. She has published numerous books: poetry, short fiction, novels and non fiction. I have always been a huge fan of her writing in all genres because, whatever she writes, it is always something that matters to me. It changes things for me both as a human and as a writer. Her latest book, The Villa at the Edge of the Empire: A hundred ways to read a city (Vintage, 2015), seemed like a good chance to ask some questions.

This book is simply astonishing. It is a book warm and sharp, so beautifully crafted, that depends upon an astute mind at work, a heart that travels and cares, ears that attend, eyes that reap images, experiences. It is a book of Christchurch; a book that signposts the city of the past, navigates the city of the present and dreams the city of the future. Both poetic and political, the protagonist Christchurch enacts a layering of cities. In this mind and that mind. From this mouth and that mouth. Here and there. It is an essential read, not just in the way it draws you into the unspeakable (a city devastated), but in the way it reminds you of what it means to live in communities. If our media (in part) is reluctant to sustain deep, keen and rigorous analysis of the ideologies and the structures that shape us, then thank heavens for a book like this. I love the fact that when Fiona embarks on a project she is not sure whether she can pull it off. That to me underlines her courage and her tenacity. If I recommend one book this year, this is it.

The Interview:

The title of your new book, The Villa at the Edge of the Empire: A hundred ways to read a city, brought to mind Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Calvino’s narrator, Marco Polo, seduces the ear of Kublai Khan with tales of marvellous cities, yet we discover these cities are the overlap of one city, Venice. A city cannot be reduced to a singular version. At the heart of your book, and it is a book with a beating heart, lies Christchurch. It is a Christchurch in physical pieces because of the catastrophic earthquake, but it is also a city in cerebral and emotional pieces, in both past and future versions, in the minds of the inhabitants. Was it a struggle to move from your embryonic starting point to the structure you choose?

I began by writing a multitude of pieces, exactly the way I would set out on writing a poem, or really any piece: just writing what was most pressing that morning. It felt particularly apt for this book as it was about structures that had fallen in pieces anyway – solid things like chimneys, but also abstract things like a feeling of security. The difficult part was assembling all those pieces into a coherent whole.

At one point you write, ‘For awhile after the quakes, there was the phantom city.’ A bit like the ache of a missing limb. What I love about your book is the way you have been the loving hunter and gatherer who pulls together some of these the missing versions. What cities have been lost? What cities have been gained?

Memory takes a while to overtake reality, I find. I remember talking to someone who had broken a leg on a tramping trip, but who managed to walk out to the road end, before feeling the most excrutiating pain. It seems as if shock can bestow a period of unreality which helps people continue to function until they have time and space to fall apart. The city lost was an assembly of routines around specific structures: walks to the cinema, or to visit friends, the way into town, the way home. The city gained is a place of surprise: I swing between enjoying the surprises of not quite knowing where the shoe shop or the bookshop or the lawyer’s office is, that makes a kind of board game of going into town, and missing the routines and structures of the past.

To me this book is vital and necessary; a book we should all read because it not only casts a light on the consequences of the earthquake but on how we shape cities as much as cities shape us. Fiona, you do this through a layering of voice. I would like to explore some of these. First there is the documentary voice. This book comes out of research but that research seems to have taken many forms. Importantly, it strengthens both the intelligence and the heart of the book. What kind of research did you embark upon?

I read and talked and walked or drove about. Kept boxfuls of clippings, read anything that felt as if it might comment on the situation, talked to anyone and everyone: the stories simply poured in. And of course I was in the city constantly, attending to my flat and its repair or rebuild and simply adapting to new circumstances in which to live an ongoing life: going to movies after a year or so when there was a cinema in which I felt comfortable; visiting friends in their motels or temporary homes, or in the places away from the city to which they had moved or in their homes once they had been repaired; finding the shops that I have always used as they resurfaced in other locations, or substitutes for the ones that ceased trading.

And then there is a narrative voice at work here delivering a narrative momentum that generates story (of a city, of many cities). Did you see yourself at some point telling stories?

Yes – definitely. Story telling is primary. It’s how we frame our lives.

The second part of this project takes the form of a novel. It will be fascinating to see how the one changes the way you see the other. What can you do in the fiction version that you couldn’t do in this version? Or vice versa?

I see this first book as the bedrock: the foundation. I haven’t felt like writing fiction during these past five years. Fact simply eclipsed it. Fiction seemed a kind of insult, really, to people experiencing such difficult or appalling narratives of fact. Why make things up, when such stories were all around? The facts were big and more than enough to occupy the imagination. I had never realized how very egocentric the action of writing fiction is: I knew it had evolved in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as an expression of a period of intense individualism, but I hadn’t truly felt that until now. Fiction seemed frivolous, self-indulgent. Poetry on the other hand felt valid: there was a tradition there of elegies and laments to validate the writing of poems. Non-fiction too was validated by the long tradition of recording facts. There was a sense of being the eyewitness, noting things for future readers.

But more recently, I’ve begun to miss fiction. In fiction, I can bring together a vast mass of disparate detail – because there are literally thousands of stories here, in archives and online and unrecorded but part of individual spoken history – into a single narrative which will I hope – and this is only hope because it might not work at all: I won’t know till it’s all finished –convey the feeling of being here. So the novel will be poised on top of this basis of fact, and together I hope they will form a document about being a citizen of a small New Zealand city in this era. That’s the plan, at any rate.

Wonderful! There is a strong political voice at work here. Insistent, incisive, astute, courageous. It embraces the personal as much it navigates the minefields of bureaucracy and government, and is always prepared to protest. Earthquake politics are astonishing.

Catastrophe sharpens perception. The politics of this event have exposed divisions that have existed all along in this country and are not particular to Christchurch, but here they have become evident in extreme circumstances.

And then there is the autobiographical voice. In writing through the filter of your own experience what discoveries did you make?

I write always to explain things to myself, no matter what the medium. My principal motive in writing the book was to try and cope with bewilderment. Seneca’s essay was written because he felt that one way to attend to fear was through understanding of the mechanics of natural events, so I picked up on that.

I wonder, too if the voice of the poet is hiding in the pen. As soon as I started reading, I was drawn into a poetic fluency. The writing is utterly beautiful at the level of the sentence. Sentences are little cascades that accrue thought and detail in their mesmerising movement. How important was the sentence?

I’m not aware of crafting sentences. I’m just trying to be clear, to myself in the first instance. If they sound good, that’s a plus! I’m pleased they do.

This marriage of thought and physical detail is a triumph in the book, yet it also resonates within the city: ‘Political theory is finding expression in bees and trees and streets and corrugated iron and stone as the frontier oppidum grows beyond the frame, up the slopes of the volcanic hills and across the plain.’ Can you comment on the way theory is laying down roots in Christchurch’s real world? Do you think at times there is a scandalous gap between earthquake ideology and the everyday world?

I quote Naomi Klein who was quoting Friedman and the opportunities for capitalism during disaster. Christchurch is a perfect example of neoliberal theory – insofar as I understand it – in action. This is what disaster capitalism actually feels like on the ground.

Does the media unpick these ideologies for us successfully?

I doubt that there is much in the book that would come as a surprise to anyone who has been living here and reading the Press every day. Elsewhere however, newspapers and tv, with the exception of John Campbell, have seemed intent on creating a PR fairytale of national wellbeing, a rockstar economy, and boundless opportunity in the south. Why and how this is happening would be the subject for another whole book. My short answer to this question would be ‘no’.

You explore the narratives of street signs as though each sign becomes a little discovery to which you were previously immune as you drove or walked past. What other discoveries stood out for you?

How very flat the city is. The buildings gave the illusion of height. But no – this was and still is, a swamp.

The section on Acquilla, and its restoration plans, is such an eye opener. The way brick by fallen brick, the city is being lovingly restored. When you move as reader from there to what is happening in Christchurch it is heartbreaking. What frustrates you most about the restoration plans for Christchurch? What gives you hope?

I don’t think there is any point in ‘might have beens…’ In any situation – personal or civic. You must deal with what is. What frustrates me most about the rebuilding of the city has been the way that central Government has constantly undermined the operation of the City Council, the transfer of absolute power to a single government minister whose personal aesthetic is clearly determining the shape of the city, the waste of money gathered from taxpayers throughout the country on rugby stadiums and convention centres for which local ratepayers are going to be paying for decades, shall I go on? I’ve tried to talk about it in calmer, more reasoned terms in the book, as I can degenerate into rant fairly quickly. Hope? Well, there are so many creative and visionary people around and once the big boys have made their pile and abandoned the sandpit, they’ll come out and restore beauty to the heart.

You mentioned your love of poetry so let’s talk about poetry for a bit.

Your poetry represents a unique and essential voice in New Zealand. There is the musical lift of each line, the surprise, the world brought closer in luminous detail. These are poems that matter at the level of being human. I am an immense fan. Were you able to write poems while working on this project?

No – I find I can’t write poetry in the same breath as prose.

What are key things for you when you write a poem?

The key thing is feeling. That’s what makes me write a poem – an overwhelming rush of feeling.

You write in a variety of genres (poetry, non-fiction, critical writing). Does one have a particular grip on you as a writer?

I love switching between genres, changing pace.

I loved the shift between poetry and prose in The Broken Book. Some critics were irked by this. Not me. It utterly worked. Enacted in a way the stuttering disconnections of a broken city. Since I first picked up a book by you (The Skinny Louie Book) I have admired your ability to push boundaries, not for the sake of breaking (as Virginia Woolf once said) but for the sake of creating. Are you drawn to smudging writing boundaries?

I like ‘making’ a book, as an artefact, something crafted, an object. So The Broken Book pleases me with its little squiggles of aftershocks and the shorter lines of the poems interrupting the blocks of prose. I like the playfulness of writing, even about serious subjects.

What irks you in poetry?

Incomprehension. I don’t mean that everything has to be spelled out, but that as a reader, I want to be able to see why the poem might have been constructed as it has.

What delights you?

Playfulness. The sense of words drawing attention to themselves.

Name three NZ poetry books that you have loved.

Bill Manhire’s 100 NZ Poems, your 150 NZ Love Poems, and Essential NZ Poems/Facing the Empty Page (edited by Harvey, Norcliffe and Ricketts).

What poets, here or abroad, have sparked you in some kind of way?

Medieval poets – Irish poems like Pangur Ban or the Old Woman of Beare, or the English monk writing ‘this passed away, this also may’. I have found that line enormously comforting in a variety of situations – not during a Viking raid, thank god.

Did your childhood shape you as a poet? What did you like to read? Did you write as a child? What else did you like to do?

Yes. Absolutely. I wrote poems throughout my childhood. Still have the collection in a school notebook that I compiled when I was about 13. I also liked riding ponies, reading and building huts.

When you started writing poems as a young adult, were there any poets in particular that you were drawn to (poems/poets as surrogate mentors)?

I guess Richard Burton reading Under Milkwood and the poems of John Donne. He had such a melting voice.

Did university life (as a student) transform your poetry writing?

I stopped writing poetry at university. Began writing essays and theses which I loved and didn’t write a thing till my dad died when I was 35. That’s when I started writing again.

Do you think your poetry writing has changed over time?

Not really. I find I keep coming back to the same kinds of themes. Life is a tangled endless thread, I’ve discovered.

Some poets argue that there are no rules in poetry and all rules are to be broken. Do you agree? Do you have cardinal rules?

No rules. Not in any form of writing. Just experiment and see what works.

I think that is why I love your writing so much in all genres. The constant mantra to be a better writer is to write, write, write and read read read. You also need to live! What activities enrich your writing life?

Sitting quietly on my own in a hut. Sitting raucously in the company of friends. Going for long walks – for weeks on end, ideally.

Finally if you were to be trapped for hours (in a waiting room, on a mountain, inside on a rainy day) what poetry book would you read?

The one closest to hand, just to see what was there.

Fiona Farrell’s web site

Pod casts

NZ Book Council author page

Penguin Random House page