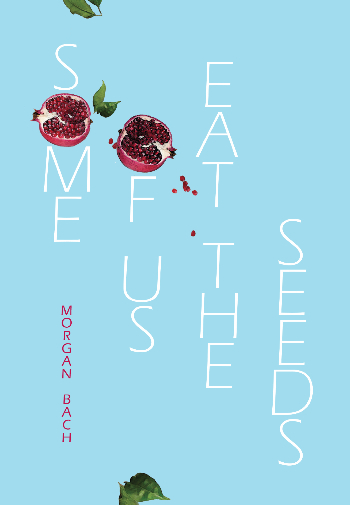

Morgan Bach Some of Us Eat the Seeds Victoria University Press, 2015

I agree with Bernadette Hall. Morgan Bach’s debut poetry collection is ‘both ordinary and extraordinary.’ Morgan is a graduate of the MA in Creative Writing at IIML where she was awarded the Biggs Family Prize in Poetry.

First up a stunning cover (cover design Rowan Heap) and a title that hooks. An allure of blue, the words a cascade downwards in white, the lush red pomegranates spilling their seeds. Gorgeous. The title resonant, already establishing a set of relations (‘us’).

What I especially love about this book is the way it plants anchors in the ground through an attachment to the real yet is unafraid to step into the smudged edges of the worlds that a mind both inhabits and produces. This is a book of collecting fruit, doing the high jump, cooking shows and vampire movies, but it is also a book of dread, heartache, anxiety, love, dreams, foreignness. The three sections are distinctive clusters (family, travel, adulthood), yet there is a satisfying drift of motifs and themes throughout the collection.

The opening poem, ‘What they made,’ is secured in self as it walks into physical detail (these feet, these eyes) and beyond that into a roving ignition of ideas (by way of a trope: ‘A person// is a weak rope’). The opening question (‘What do I inherit?/ A split face// the eyes of one/ the sighs of another’) is particular apt in a book that faces memory, and in doing so represents myriad versions of self. The resulting poems are both invigorating and effervescent.

Take the title poem for example. The poem houses a jiggety mind at work, a mind walking (walking is a reoccurring device) into the fuzzy, elusive and utterly fascinating pull of memory, with its shifting and established myths, where ‘our country’ is not entirely accessible let alone knowable.

(..) The past is a tether

you don’t need to wear. Time has

its own ways of making people disappear.

Poems become frames for disappearances, for a vanishing (after terrific citations from Mary Ruefle and Adrienne Rich). You can link these unsettling and uncanny departures to memory, to the way things can not remain present reachable fathomable. The way in recuperation things change. Reading through the collection with this fertile knot is provocative yet nourishing. In anther poem, ‘His binding land,’ the disappearance is like a plot cog. A father walks away and off to ‘the paddock/ he called the back of beyond’ to lie ‘in the dew, unblinking/ as the morning changed/ with the cambered spring sun/ into full day.’ This little paternal disappearance resonates so beautifully and is a perfect example of how Morgan leaves a trail of physical traces to spark miniature narratives connections possibilities. Delicious. And then the end of the poem that is poignant, the language sweet in its simplicity: ‘When evening/ slid up and over, his wife/ walked out to find him.’

I posted ‘In pictures’ on Poetry Shelf awhile ago with a note from Morgan and a note from myself, and was surprised to learn the story of the deaths. Morgan’s father was the actor, John Bach, and the countless deaths she had witnessed were on stage. This constitutes another disappearance and is the hallmark of much poetry; what the poet chooses to reveal and conceal. and whether not to use endnotes, can alter the navigation of a collection. Notes to the poem’s genesis can be fascinating and enlightening but I am equally happy to enter without guy ropes.

The first section, with its poems that draw upon family, family relations and childhood struck a chord with me. I stalled in this section. I got hooked and sent flying, hooked and sent flying. Here there is a richness of line, striking invention, a muscular layering. ‘The swimming pool’ evokes childhood to beautifully, through physical detail yes (Most of the day you’d lie/ on warm concrete/ beside the pool that was cold as needles’), but through so much more than this. The poem shows how childhood is also a state of mind to resist and adore.

I also loved the inventiveness of some of these poems, audacity even. In ‘Vampires,’ Morgan meshes together watching a British cooking show with family, choosing a vampire movie and walking through devastated Christchurch. The result, a sweet interplay of striking connections and overlap.

Here is a sampler of some of the lines that have stuck with me:

‘In that season life was ripe for the feast– plums and lemons, figs, apples; everything fell.’

‘We’re at the centre/ of what we know. We’re brains// and sight.’

‘I see myself alone on a swing/ and watching’

‘Forgive me then if I always// write about watching,/ it’s what a lonely child// does, even when she ventures/ over oceans.’

There is a strong sense of composition to the collection as a whole. The middle section begins and ends with the cold, inventively, fascinatingly so. In the first poem, ‘Cold,’: ‘In that time we ate only the darkest snows/ and felled lights, brittle paintings.’ The poems travel, they take to the core people and places, otherness foreignness. This line stood out: ‘There are never the right postcards.’ And so it is as if the poems become surrogate postcards with willowy lines leading us to elsewhere. And always the roving mind, the courage to layer ideas alongside heart and acute observation: ‘Take as much time as you have, build the house in your head.’

The final section with its adult yearnings displacements recognitions pulls uou from betrayals to desire, from love to heartache. I adore ‘This is how to write a love poem’; the way it is aware of its own making (could be old hat as self-reflexivity has been done to death, but here it is refreshed and vital. This is a cluster of love and not-love poems that burst at the seams with flavour impact vulnerability.,

Reading Morgan’s debut is utterly rewarding as it sets every part of your readerly self on high alert, every bit paying attention to the pulse of the poem, each poem needing the grit of daily life, the surprise and flight of a daring mind, the traces of real life, the miniature stories, the lines that move in the ear so beautifully. Ordinary, extraordinary and yes, astonishing.

Within the next week or so I will be posting an interview with Morgan.

VUP page here

‘In pictures’ on Poetry Shelf here

Posts about Morgan Bach in The Red Room