I am heading off to Wellington this morning to go to A Circle of Laureates, the Lauris Edmond prize event and do a smidgeon of reading in between. Thought I would share these first:

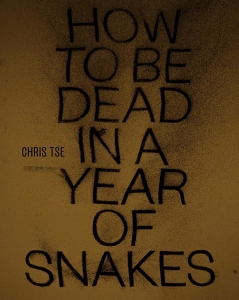

How to Be Dead in a Year of Snakes Chris Tse, Auckland University Press

Chris Tse is a writer, musician and actor whose poetry first appeared in AUP New Posts 4 (Auckland University Press, 2011). He resides in Wellington, his home town.

Chris’s debut collection, How to Be Dead in a Year of Snakes, responds to a moment in history not so much by narrating that history but by installing a chorus of voices. He takes an event from 1905 when Lionel Terry went hunting for a Chinaman in Haining Street, Wellington and ended up murdering Joe Kum Yung. Within the opening pages, the chilling event is situated in a wider context where laws proscribe the alienness that situates Chinese as outsiders. This is what gets under your skin as you read.

The poems draw upon and draw in notions of distance, defeat, guilt and forgiveness. There are the unsettled imaginings of what it is to be home, to be at home and to be out of home to the extent that home becomes difficult and different. Mostly it is a matter of death (and casting back into life) whereby phantoms stalk and cry about what might have been and what is: ‘You spend your thoughts drowning in your family-/ missing from this vista- and contemplate a return with nothing to show/ for your absence.’

The collection harvests shifting forms, voices and tones that promote poetry as mood, state of mind, emotional residue. Yes, there is detailed evidence of history but this is not a realist account, a story told in such a way. Instead the poetic spareness, the drifting phantom voices give stronger presence to things that are much harder to put into words. How to be dead, for example. How to find the co-ordinates of estrangement, of that which is unbearably lost and is hard to tally (family, home, what matters in life). On page four you move from a matter-of-fact representation of the law to page five and the wife in Canton (‘you carry her bones in your body’). Two disparate but equally potent aches.

For the rest of the review see here

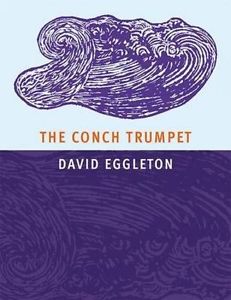

From an interview I did with David Eggleton last year:

I love the title of your new collection (The Conch Shell, Otago University Press). The blurb suggests that this collection ‘calls to the scattered tribes of contemporary New Zealand.’ What tribes do you belong to? What literary tribes? How does the word ‘contemporary’ modify things?

Yes, I’m blowing my own (conch) trumpet at sunrise. That title refers to tide-lines of life, to surf-like sounds, to gathering good vibrations, to gods of the sea who, clarion-like, lull the waves, and to the summer of shakes, the year of quakes. And so on, to the final burnout of the run-ragged consumer. The rest is the tribal outcast, and everything you cannot pin down, or ascribe a bar code to.

In fact, the word ‘tribe’ is fraught. I think James K. Baxter brought it into the literary realm. My own tribal background is distinctly heterogeneous rather than Fonterra-homogenous, but if I look around at my contemporaries, poets and otherwise, I see most of them making it up as they go along. A poem tests a proposition; it doesn’t always prove it.

These new poems offer shifting tones, preoccupations, rhythms. What discoveries did you make about poetry as you wrote? The world? Interior or external?

My poems like to dwell on the silver wake of a container ship, or the wet sand beneath the upturned hull of a dinghy, or the half-seen, the overheard. Poets re-arrange, but they have duties of care. X.J. Kennedy has pointed out that: ‘The world is full of poets with languid wrenches who don’t bother to take the last six turns on their bolts.’

It’s been five years since my last poetry collection Time of the Icebergs appeared, and one reason my collections have been regularly spaced that far apart is the need for more elbow-grease and line-tightening to get the burnish just so.

The poet’s mind, like anyone else’s is made up of reptilian substrate, limbic empathy and neo-cortical rationality. These shape your reveries and hopefully together lift them out of banality. Our ideas are dreams, styles, superstitions. We rationalise our temperaments, draw curtains over our windows, but poems carry an anarchic charge that reveals the force that through the green fuse drives the flower.

A poet is in the business of the unsayable being said, showing you fear in a handful of dust. A poet is amanuensis to the subconscious ceaselessly murmuring, and indeed to the planetary hum, the gravitational pull of the earth, the wobble of placental jellyfish in the womb — anything alive, mindless and gooey.

Is there a single poem or two in the collection that particularly resonates with you?

Every poem resonates on its own wavelength, but I found constructing an immediate elegiac response to my father’s death one of the most turbulent. A bit like getting to grips with a storm, with a howling wind that has shape and substance.

Returning to the notion of detail, I see the accumulation of things in your poems as an overlay of highways to elsewhere whether heart, issues, ideas, fancy, memory. Yet the things also pulsate as things in their own right. What draws you to ‘the thisness of things’ (the blurb)?

Things accumulate in my poems in almost haptic fashion, wrestled there like sculptural ingredients. They accumulate, as in the random haphazard assemblages of the Dadaist Kurt Schwitters, built out of found objects in the streets. Yes, I want to acknowledge the ‘thisness’ of things, but not in the sense of ‘property’. Rather, in the sense of: he who kisses the joy as it flies, lives in eternity’s sunrise.

For the complete interview see here

Tim Upperton, The Night We Ate The Baby HauNui Press, 2014

Tim Upperton’s debut poetry collection, A House on Fire, was published by Steele Roberts in 2009. Since then, his poetry has been published in numerous journals and he has won awards for a number of them. The poems for this new collection were written with the assistance of a Doctoral Scholarship from Massey University of New Zealand, so perhaps they form/formed part of his doctoral submission. Tim will be reading as part of the Haunui Press ‘Deep Friend Poetry Reading’ series at Vic Books on 26th March. Details here.

This latest book is unlike any other collection I have seen in New Zealand; chiefly in terms of the measure of discomfort. The forms are various, scooping an edgy wit into prose blocks, villanelle, triplets, couplets and freer patterns. Yet there is connective glue at work here, and that is what makes this collection stand out. I think it comes down to voice (whether or not it is the personal voice of the poet doesn’t really matter) because the voice steering the poems is sharp, forthright, witty, edgy, grumpy. It unsettles. It keeps you on your toes. On the back of the book, Ashleigh Young suggests that ‘[t]hese willfully, calmly disagreeable poems have tenderness and courage at their heart.’ I would agree. Therein lies the pleasure of reading these poems; there is more to the brittle edginess than meets the initial eye.

The first poem, ‘Avoid,’ very clearly announces that this is a poet who loves language, that is unafraid of rhyme and rhythm working arm in arm. The poem is a miniature explosion of sound effects — with sliding assonance, bounding consonants, near rhyme and sumptuous aural connections. It brought to mind the refrain in Don McGlashan’s song, ‘Marvellous Year,’ and Bill Manhire’s glorious ‘1950s’ in the use of rhythm and rhyme, and aural trapeze work that is ear defying. Whereas Don’s song represents a potted portrait of the world in all its warts and glory (in a marvellous year), and Bill’s poem is a nostalgic recuperation of things, Tim sets up the collection’s negative disposition and itemises things to avoid!

For the rest of the review see here

Roger Horrocks Song in the Ghost Machine

I haven’t read this book! Last year I picked it up to review then found something about it was very close to a fragile starting point I had for a book in my head. I can’t talk about poems I am writing until they are written. I didn’t want to scare my starting point off so left in the pile to read.

Now that I am hard at work writing about NZ women’s poetry, my starting point is in a little holding bay where it may or may not survive. It has been there for over a decade though and has moved to second place in a queue.

So I am throwing caution to the wind and taking this book to read on the plane.