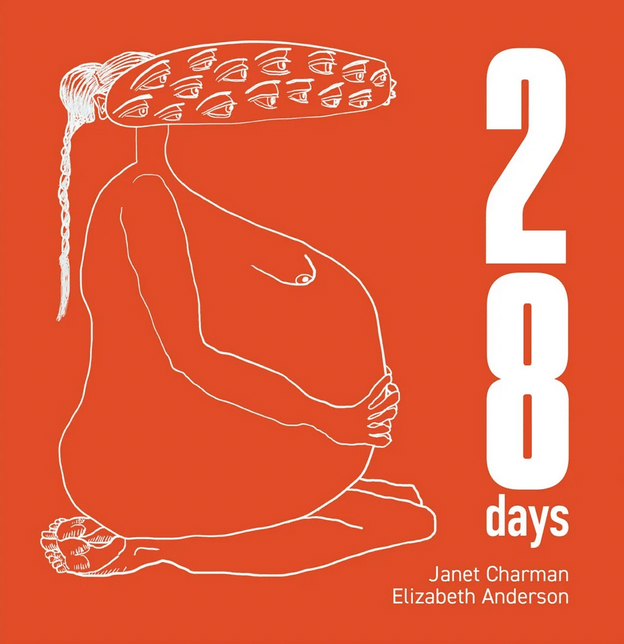

28 days, Janet Charman and Elizabeth Anderson

Skinship Press, 2025

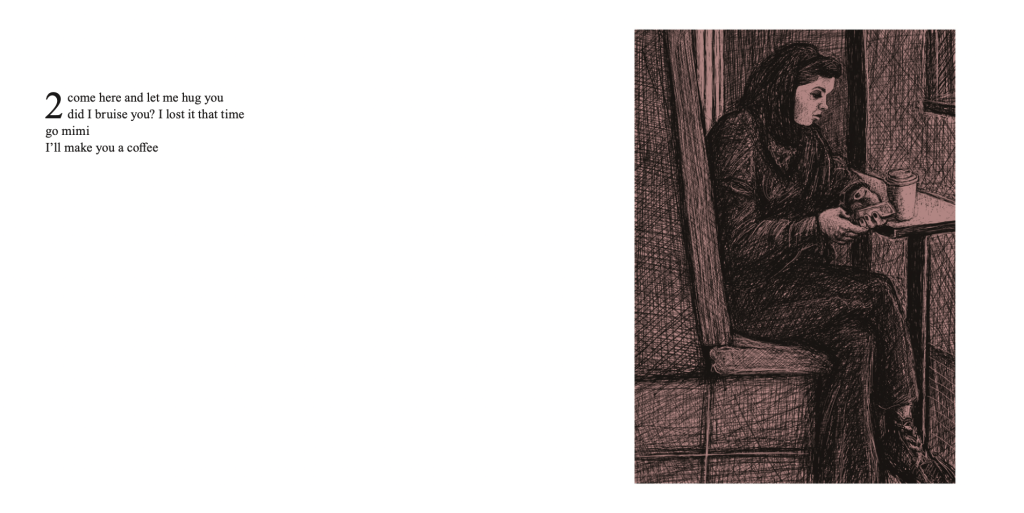

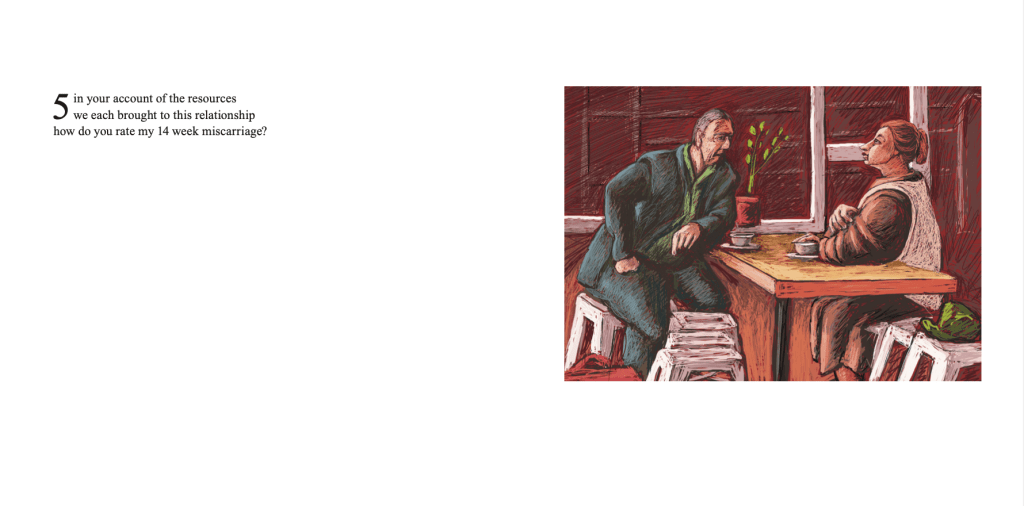

I am sitting at the kitchen table, the doors wide open, feeling the wind rustling in from the Waitākere ranges, the bird song racketing after all that rain, my flat white growing cold, and I slowly reflect upon 28 days. The book fits in the palm of my hand but expands in prismatic ways in both heart and mind. I have never experienced anything like it. It is pitched as a creative memoir. Elizabeth Anderson has produced 28 artworks, Janet Charman 28 texts. The artwork focuses on cafe scenes, drawing upon multi media, echoing Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Parisian café paintings. The little texts – dialogue or poems or anecdotes – are like word kisses on the page.

The memoir is a collaboration, a contiguous relationship between word and image, between artist and writer, and this brushing close, this besidedness as the blurb says, is utterly fertile, utterly heart expansive in its reach. I am stretching for words, and they slip away. So I sit here on the rim of weeping, weeping at the way I’m brought cheek to cheek with the sharp edges of humanity. The shadows. My shadows. The unspoken. My unspoken. There in the cafe settings. There where dark brushes against light, where isolation and loneliness are rife. There where stories are shared, and equally stories are held back. Darkness and light.

Probably against the grain of reading a sequence of images and text, I look at Elizabeth’s images first. She produces all the drawings on her iPad using the Procreate drawing app, recording her observations in cafes or buses. I am absorbing the people frozen in a cafe moment, those on phones, those alone, those in groups, those with son or daughter, and each scene amplifies an intensity of mood. I can’t think when I have last felt portraits to such a degree. I feel the gaze of the eyes, the expression on the face. I feel the unspoken, and more than anything, the way we become a catalogue of memory, experience, pain, aroha, longing, recognitions.

In these tough times that can be so overwhelming, this book, I am feeling to its raw mood edges.

Now I return to the beginning and read Janet’s texts, these little patches of dialogue or poetry or anecdote, and again I am shaken to my core. It’s dark and light, its jarring and surprising. It’s gender relations and damage and patriarchy and femen and abuse and dressing wounds and how do we become and how do we be. Interior monologues, intimate revelations. Again I am feeling this book, feeling poetry to a skin tingling degree.

I am reading through the book for a third time, text alongside image, image alongside text, and the besidedness is extraordinary. It takes me deep into grief, into how we live, how vital our stories and conversations are, how connectedness matters, how listening to the person beside us matters. How important it is to nourish our children and ourselves in multiple self-care ways. And my words are a knot. How to re-view? How to speak? How to write?

Janet and Elizabeth’s collaboration began during the Canal Road Arboretum protest in Avondale, where the two artists first met. The book is in some ways a form of protest, in another ways a memory theatre, an intimate album. I haven’t felt a book this deep in a long time. This book is a gift. And I have ordered a copy to gift to a friend. Thank you.

Janet Charman is an award-winning poet, recipient of the Best Book of Poetry at the 2008 Montana New Zealand Book Awards. Her 2022 collection The Pistils was longlisted at the 2023 NZ Book Awards, and her 11th collection The Intimacy Bus was released in 2025.

Elizabeth Anderson is an artist and educator with an MFA from Elam. She has worked across design and television in Aotearoa and the UK, and now focuses on observational drawing and community-based creative work.

Skinship Press page