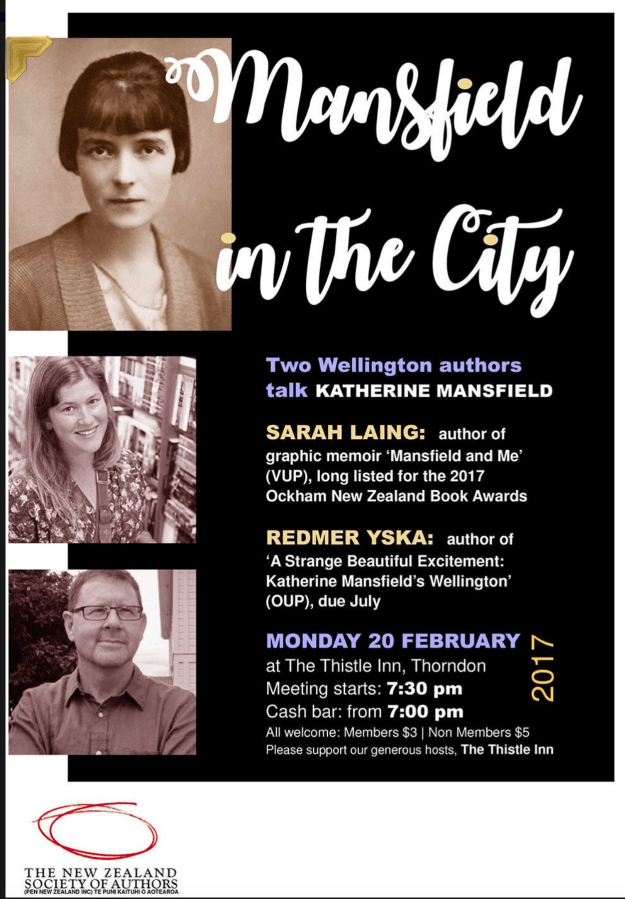

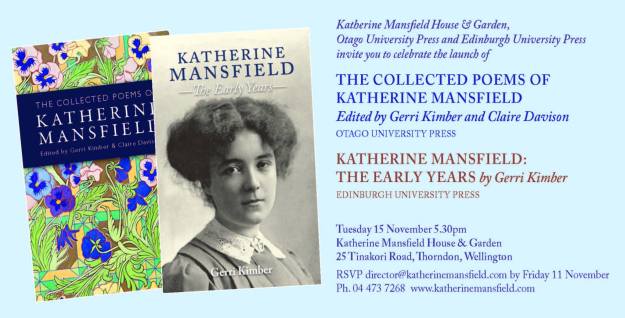

The Collected Poems of Katherine Mansfield edited by Gerri Kimber and Claire Davsion, Otago University Press, 2017

Otago University Press recently released a beautiful hard-cover edition of Katherine Mansfield’s Collected Poems edited by Gerri Kimber and Claire Davison.

Gerri Kimber is a visiting professor in the Department of English at the University of Northampton, UK. She is co-editor of Katherine Mansfield Studies and chair of the Katherine Mansfield Society. She devised and is series editor of the four-volume Edinburgh Edition of the Collected Works of Katherine Mansfield (2012–16).

Claire Davison is professor of modernist studies at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris III. She is the author of Translation as Collaboration: Virginia Woolf, Katherine Mansfield and S.S. Koteliansky (2014). Her ongoing research focuses on trans-European modernist links on the radio in the 1930s–40s, and the links between modernist literature and music.

When Vincent O’Sullivan edited a smaller selection in 1988, he did not have access to the more recent discoveries such as ‘The Earth Child’ sequence, and he purposefully omitted Mansfield’s ‘mawkish Child Verse: 1907.’ O’Sullivan introduces Mansfield and her poetry in a somewhat different vein than the editors of the new book do. He suggests that John Middleton Murray scrambled to get Poems by Katherine Mansfield out the year after her death, but that she had not attempted to get this work published herself. Indeed O’Sullivan suggests that while ‘she returned to writing verse at different times during her life, Mansfield made no claims to being a poet.’ O’Sullivan offers two reasons to read the poetry of Mansfield:

‘We may regard her poetry now as Mansfield herself tended to think of it—unassuming, often slight, serviceable enough for occasional published excursions into inherited effects and derived styles, yet capable too of unexpectedly inventive turns and intensity. Or we may read it for its vivid biographical faces, the quick clarities of her attention as it catches at angles of memory or self-scrutiny’ (‘Introduction,’ Poems of Katherine Mansfield).

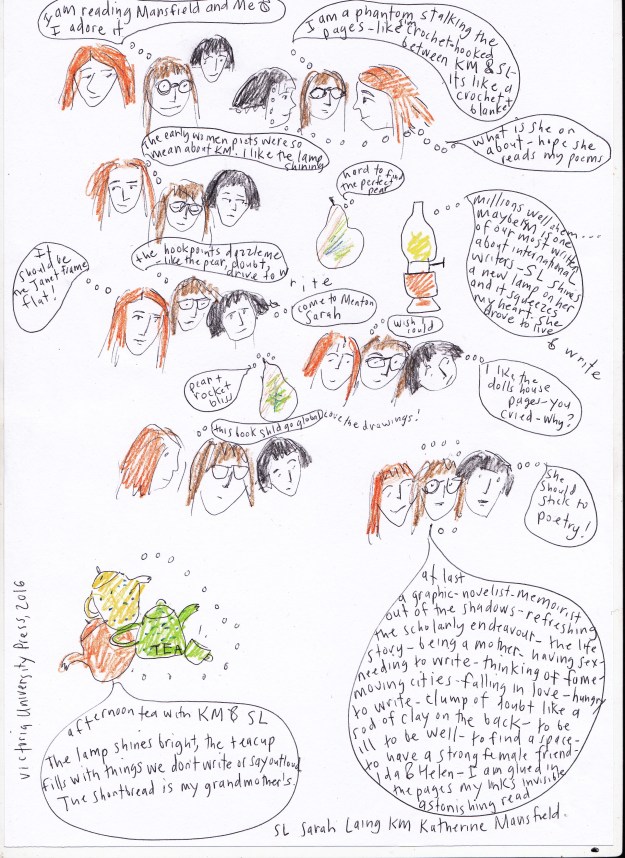

I read my way through the Collected Poems before I read the poem notes or either introductions because I wanted to make up my own mind about what Mansfield’s poetry was doing. Would the poetry afford interest at the level of the poem or would it simply seduce me with biographical traces? I find myself positioned halfway between O’Sullivan’s approach and that of the new editors. I find the biographical residue fascinating and I find poems that startle and shine but I also spent a long time pondering the way in which the child drives the poetry. I am not going to write Mansfield’s poetry off as naive and child-like, but it is a complicated and intriguing issue that I want to explore elsewhere. Having spent the past year researching early New Zealand women poets, it seems that Mansfield was producing something altogether different.

Kimber and Davison make big claims for Mansfield in their introduction:

‘Mansfield’s poetic art may lie in briefly surveyed scenes, passing voices and imagist-type glimpses, but they constantly connect to the wider socio-political realities around her. Hers is a poetic voice that requires us to rethink the lyric, and recall that, across the centuries, lyric poetry has never been synonymous with simply ‘being lyrical.’ Even when Mansfield’s immediate subject matter may be mere snippets of everyday life, and even when the poetic voice appears to be laughing, her “cry against corruption” is still clamouring to be heard: war, the condition of women and other socially marginalised groups, poverty, class consciousness, sickness, bereavement—these themes too can provide the stuff her poetry is made of (‘Introduction’ p21-22).

Despite various quotations from Mansfield’s letters to clarify her relationship with poetry, I am not convinced that poetry was her number-one writing love. Poetry served a purpose, perhaps multiple purposes, at particular times, and on many occasions, represented exquisitely framed observations, memories, feelings. The poem became a vehicle of self, both introspective and outward reaching, and drew upon some of the themes Kimber and Davison list.

What makes the collection essential reading for me:

The opportunity to follow the absorbing development of Mansfield’s poetry from young girl to young woman

The way child-like things endured

The way the persistent themes of love, isolation, natural beauty, freedom and illness nourished the poetic ink

The way KM stepped (wrote) outside herself in order to see (write) herself

The way some things (New Zealand, her husband, her writing life) were barely visible or audible but left a presence on the tongue as I read

The way some things (her brother, her grandmother) were sharp and potent and surprising like little keepsakes to be borne forever

If Mansfield’s poetry requires us ‘to rethink the lyric,’ so do a number of New Zealand women poets writing at the time. Perhaps I am more inclined to say we need to re-tune how we read these early women poets. I see Mansfield’s poetry evolving outside the labyrinth of local women, but like these pioneering writers, there are continual adjustments to rhythm, rhyme, revelation, reserve, ideas, feelings, aims; to the writing of the lyric. For me Mansfield’s poetry is still a puzzle that I need to think and write about more extensively before I can make any claims, however tentative they might be, particularly in view of the child. But I am caught in the clarity of her writing, the distilled or vivacious mood, the melancholy, and I like it.

What I can do is offer a tasting plate of some highlights as I read:

from The […] Child of the Sea (1906)

Here in the sunlight wild I lie

wrapt up warm with my pillow and coat

Sometimes I look at the big blue sky

from ‘London London I know what I shall do’ (1907)

London London I know what I shall do

I have been almost stifling here

And mad with love of you

from Little Brother’s Story (1908)

I made up one about a spotted tiger

That had a knot in its tail

But though I liked that about the knot

I didn’t know why it was put there

from Loneliness (1910)

Now it is Loneliness who comes at night

Instead of Sleep, to sit beside my bed.

Like a tired child I lie and wait her tread,

I watch her softly blowing out the light.

from Sea Song (1910)

Memory dwells in my far away home.

She is nothing to do with me.

from Violets (1910)

The room is full of violets –

And yet there’s but this little bowl

Of blossoms on the mantle-piece.

from Scarlet Tulips (1913)

Strange flower, half opened, scarlet

So soft to feel and press

My lips upon your petals

Inhaled restlessness

from Camomile Tea (1916)

Our shutters are shut, the fire is low,

The tap is dripping peacefully;

The saucepan shadows on the wall

Are black and round and plain to see.

from ‘Lives like logs of driftwood’ (1916)

Lives like logs of driftwood

Tossed on a watery main

from Pic-Nic (1918)

And she crawled into a dark cave

And sat there thinking about her childhood

Then they came back to the beach

And flung themselves down on their bellies

Hiding their heads in their arms

They looked like two swans.

from Men and Women (1919)

I get on best with women,’

She laughed and crumbled her cake.

from The New Husband (1919)

Who’s the husband – who’s the stone

Could leave a child like you alone.

from Et Après (1919)

She was hard to please

They’re better apart.

from The Wounded Bird (1922)

In the wide bed

Under the green embroidered quilt

With flowers and leaves always in soft motion

She is like a wounded bird resting on a pool.