Luminescent is one of my favourite poetry reads in 2017. Check out this new interview with Helen Rickerby.

Luminescent is one of my favourite poetry reads in 2017. Check out this new interview with Helen Rickerby.

Tightrope, Selina Tusitala Marsh , Auckland University Press, 2017.

Let’s talk about unity

here in London’s Westminster Abbey

did you know there’s a London in Kiritimati?

Republic of Kiritibati, Pacific Sea.

We’re connected by currents of humanity

alliances, allegiances, histories

from ‘Unity’

To celebrate Selina’s new poetry collection, Tightrope, and her appointment as our current New Zealand Poet Laureate we email-conversed over several weeks. Selina is of Samoan, Tuvaluan, English and French descent. Her debut collection, Fast Talking PI, won the Jessie Mackay Award for Best First Book of Poetry. She was the first Pacific Islander to graduate with a PhD in English from the University of Auckland. Last year as Commonwealth Poet she performed ‘Unity’ for the Queen at Westminster Abbey.

‘I leapt for joy when I found out our new Laureate was Selina. Firstly because I am in awe of what she writes and she is a good friend. Her latest book catches you from first to last page on so many levels. Secondly I follow behind her at schools and I can see how she has utterly inspired teachers and students, whatever the level. This is poetry gold. Thirdly I leapt for joy because that now makes it 5 women poets out of the 11. Did it matter to me that a woman was picked -yes it most certainly did. Selina has talked about the way she wants to have 1000 hands touch the tokotoko – how she wants to bring the poetry of brown faces to the spotlight. When I look about and see how whitewashed we are in so many ways – what gets published, what gets reviewed (check out the latest list of best poetry books 2017 in The Listener), what gets put stage centre at festivals, journal content etc – I leapt for joy that we have Selina. Hone Tuwhare and Sam Hunt are the two poets that are so beloved by our nation. I predict Selina is our third. I am currently writing a book on NZ women’s poetry and while my aim is to showcase the poetry that so often gets eclipsed by theory and dogma and bias, I also, at times, talk about the woman holding the pen. She has existed in the shadows. She has been maligned and misunderstood and devalued. I want to give women poets presence where it seems apt because their stories have so seldom been told. So while I think the poem is the first most paramount thing, I also think it is important to navigate the difficulties and triumphs women have faced as poets over the past century in New Zealand; how their poetry has been denigrated and erased due to gender or race. To have Selina given this golden opportunity to write further into our sightlines is heartwarming.‘

Paula Green 10 October 2017 on Facebook

Our conversation

Paula: I have spent a stormy Sunday morning lying in bed reading your new poetry collection, Tightrope, from cover to cover, and now I want to read it again slowly as an email conversation unfolds between us. The reading experience moved shook soothed challenged diverted me with the ooh and aah of recognition pain delight. In other words, the poems take you so many places in so many ways. I love it!

Gran’s jasmine

delicate pink

heavy and sweet

clings to the bone

from ‘Kiwitea Street in the ’80s’

The cover is striking with the tightrope moving from top to bottom rather than stretched taut across a horizontal line. I had held up my piece of red wool at your book launch, but it is only now, I am wondering why it holds a vertical line. It as though the rope stretches from the sky (heavens) to the earth (grounding), or from earth to sky. It is like an upturn, an overturn, and is infinitely resonant in its red to green glow. Why this placement?

Selina: Instinctively insightful as always Paula. In part, it references the living conditions of what I think of as the first poem of this land – the poetic parting of Papatuanuku, Earth mama and Ranginui, Sky dad, and the struggles of living before, during and after their separation. What does it mean to live in between such aroha, such passion, such angst? Sometimes, like this morning, it means submitting to Tawhirimatea’s restlessness in the driving wind; other times, it means tuning into a mist-like longing in the light after-rain. I’m often in between. As a middle child I’m used to it and have finely honed skills of negotiation. Inbetweeners possess tightropish qualities: a tender balance between joy and pain; the toe inching forward of a line that demands feeling before seeing. That’s why the line is raised (much to Michele Leggott’s joy, who proclaimed at the Devonport Library launch recently that it was one of few books which she could hold up to an audience and know it was rightside up!) Because I feel my lines. Because that’s what brings me out of the abyss. It’s also what gives depth to the abyss.

Unity is an underlying theme in the collection, as well as being the title of the poem for the Queen. Unity is what’s needed in ‘the struggle’, however you define it in your life at that point (evoking the brothers’ struggle against the darkness imposed on them by their parents). Unity is what my poetry seeks to create. Unity of the multitudinous stories that constitute our memory, which in turn, form our history, ‘the remembered tightrope’, to quote Albert Wendt. The morphing colours of that beautiful vertical rainbow line (thanks Katrina Duncan and Spencer Levine) evokes the many hues of our lives that refuse to be forgotten.

Al,

I’ve taken a black vivid marker

pressed it against your page

and letter by space by word by phrase

inked across your lines

streaking pouliuli pathways

wending in and out of the Void

from ‘The Blacking Out of Pouliuli (1977)’

Paula You climb reverse-wise through Albert’s quote, so to speak, in your three sections: from the abyss to the tightrope to the trick. It seems the poetry pollinates the inbetween space between forgetting and remembering. He places this in view of history, but is it also personal?

‘We are what we remember, the self is a trick of memory … history is the remembered tightrope that stretches across the abyss of all that we have forgotten.’ Maualaivao Albert Wendt

Selina: History is deeply personal, after all, it’s ‘written by the winners’, as I first saw in my undergraduate years graffettied under Grafton Bridge as my bus was heading out to Avondale (and later attributed to Churchill). I’m reading a delicate collection of poems titled ‘Luminescent’ by Nina Powles at the moment (PG: my review here). 5 chapbooks are stacked in a fold out box (Seraph Press does a beautiful job) and each of them speaks back to women figures – some famous (I especially like the poem ‘If Katherine Mansfield were my best friend’) and some lesser known (to me), like ‘The Glowing Space Between the Stars’ responding to the award-winning New Zealand cosmologist Beatrice Tinsley (1941-1981), who ended up at Yale University teaching on galaxy evolution. Where was her history in school? Nina’s personal, poetic connection with five (early) New Zealand women is helping to build this history.

I think that’s why I so love Al’s line ‘the self is a trick of memory’, because that’s the personal self (‘Queens I Have Met’, a way to memorise moments), the communal self (‘The Dogs of Talimatau’ – how did all those dogs really die?) and the national self (from the New York poems, see for example ‘Inward Hill, New York’ – what happened to the indigenous people of Manahatta? – to Oceania’s ‘Atoll Haiku Chain’ – Tahiti’s stories fan the flames of its history of colonisation, nuclear testing, and protest. That inbetween space between forgetting and remembering though, is probably most potent in the abyss of death, but ‘Essential Olis for the Dying’, the poem written for my beloved colleague and ‘shooting black star’ Teresia Teaiwa (1968-2017), to whom this collection is dedicated, appears in the ‘Tightrope’ section. That’s because, to quote Al again, ‘we are what we remember’, and we choose to capture moments of relationship that are ephemeral by nature, that’s the act of tightrope walking.

We choose, inch by inch, what we will feel beneath our toes, how we will balance ourselves in the air and keep our centre of gravity so that we can keep moving forward. Certain moments, particular memories, we will throw across the abyss of time in order to reach back while moving forward. Other things will recede into the background – we think we’ll never forget, but then we do. We lose shades of it, pieces of it, and even though the loss stays, even that, the depth of it, the pain of it begins to diminish over time. Maybe it’s meant to.

Take this cardamon

to ease you into the next plane

not the one taking you back to Santa Cruz

or Honolulu or Suva

but the next plane.

from ‘Essential Oils for the Dying’

Paula: I also love Nina’s collection and the way she is casting light on these five diverse women. That you dedicate your collection to Teresia Teaiwa resonates deeply, on an individual level, but also because you are part of a weave of women writing, speaking, sharing. You don’t write out of a vacuum.

I was particularly moved by, ‘Apostles’ and the way it challenges on so many levels. Alice Walker lays down the first challenge:

Alice Walker said

before placing a red

cushion in the middle of the road

that poetry is revolutionary.

You recount events that speak to such a claim. I am musing on way you highlight the example you accidentally found when googling lime; a brown skin woman mob tortured for sorcery. Not famous; one woman suffering. Do you think poetry can make a difference?

A brown woman is sitting

her back to us

bare on a corrugated

iron dock

noose round her neck

wrists bound

machete bites

mar her back

one gash so deep

its creviced meat

blackens

in the smoking air.

from ‘Apostles’

Selina: ‘Apostles’ is my answer to that question, which is answered by a question back to Alice Walker, poet, writer and activist extraordinaire: ‘Alice, how can a poem possibly revolutionise?’ Then Kepari Lenara, the name of the young woman murdered by mob, appears and fades over the following lines. These visually echoing whispers evoke the power of orality at the heart of poetry. Poems are meant to sit on the tongue, be spoken and sung, flung into someone’s ears.

One of my favourite lines of all time is by poet and lyricist Rangitunoa Black: ‘A fire burns on the tip of my tongue, I should cry to put it out.’ That’s the power of poetry, that it matters, that it creates fire and movement out into the world. It’s why the Poet Laureate Matua Tokotoko (parent tokotoko) is so gorgeously poetic. The parents have three detachable sections to them (to enable easy travel!). It comprises of a mama section (which has a hand written poem by Hone Tuwhare in its belly) and a papa section (which has a grooved tip). When you rub them together – ahi! Smoke! Isn’t that what poetry is about? It’s why I’d love love love to have a flint embedded in my own tokotoko so in performance, I can strike it and create that spark. A living metaphor. A heightened engagement with the audience. An interactive poetry. That’s the difference poetry can make. And poetry has made a tangible difference in my life. Poetry enabled me to articulate my turangawaewae (standing place) at university as nothing else could. Poetry can make a difference. That’s why I take it out to schools, community halls, corporate boardrooms. For the difference it can make.

Paula: And you take it to your sons in ‘Warrior Poetry’. It is like a letter coming from the gut, saying this is what I do, but it also feels like an energised song-chant-poem for teenagers, especially boys, who skirt books and poetry.

Putting together a poetry collection, boys

is like the NLR nines

Eden Park, 45,000 packed

you’ve got 90 pages of lines

to work the eclectic crowd

into some kinda synthesis – some kinda wonderful

from ‘Warrior Poetry’

Poetry does many things in your collection – even act as a little spot of revenge! Ah! the revenge poem.

Selina: Poetry for all occasions right? You see, often in a difficult, embarrassing, confronting, uncomfortable situations, my first reaction is to smile (my kickboxing trainer used to call me the ‘Smiling Assassin’). It’s only later when the brilliant retorts, the intellectual one-liners, the sardonic replies, come to the tongue. Or I should write, the pen. And poems can carry the weight of my anger or angst; they can take the push-pull of my righteousness and ambivalence (at the same time); they can turn a moment of indecision about what just happened or shock at someone’s rudeness or felt gut-disempowerment and re-story it ways that return power to me. Call it ‘the revenge poem’ or call it ‘the re-storying painful or uncomfortable events poem’, whatever you call it, its at all of our fingertips!

My moana blue Mena

My Plantation House shawl

My paua orb

My Niu Ziland drawl

My siva Samoa hands

My blood red lips

My va philosophising

My poetic brown hips

from ‘Pussy Cat’

Paula: Five poets were Te Mata Estate Poets Laureate, with Bill Manhire (1996) and Hone Tuwhare (1997), the first two. In 2007 the National Library took over the administration and appointment process and selected Michele Leggett as the first New Zealand Poet Laureate. You are the sixth Laureate appointed by the National Library with the change in title.

Looking back across the Laureate blogs and tenures, each Laureate seems to shape the role to fit him or herself, just as the tokotoko is carved by Hauamoana artist, Jacob Scott, to fit the individual. I love the idea that you will shape the role to fit – what matters to you as Poet Laureate?

Selina: In 2 weeks I leave for Samoa where I’m judging the Pan-Pacific Tusitala Short Story competition, giving the keynote for the Pacific Arts Association, running two writing workshops, and performing on opening night. While this was arranged well before becoming Poet Laureate, I am taking the Matua Tokotoko with me and ‘they’ (the parents) will feature. Usually behind lock and key in a glass case at the National Library in Wellington, I have instinctively known, as a person from the Pacific, the taonga, the national treasure, that I have in my possession.

Polynesians know the mana such taonga possess. Material objects become taonga as they are passed on and down; as they pick up the stories, histories, and genealogies of those who possess them. I will have reached my goal of a 1000 pairs of hands touching the Matua Tokotoko in Samoa (I’m currently at 977) since the Award was announced on August 25th. Everywhere I go people are enthralled with the story of its making – but it’s not really common knowledge. That’s what I want to do, at least among the diverse communities I engage with. Most are not aware of what the Poet Laureate is, nor what the tokotoko represents. Each Laureate has helped increase awareness in their own circles, in their own way. That’s what I’m doing now.

After visiting Hawkes Bay and finally having a korero with carver Jacob Scott from Matahiwi Marae, we’re really excited about bringing my tokotoko into the world. This trip to Samoa will also enable my Samoan treasures to be included in its making. One idea was that I source (that means ‘cut’) some wood from my grandfather’s house in Elise Foe, the original ‘Tusitala’, to include in the carving. Then when I visit Vailima, Robert Louis Stevenson’s plantation house, I do the same there (with permission from the owners) and source material from the other ‘Tusitala’ to somehow incorporate. I’d like to bring home a stone from the river my mother used to bathe and play in. I’d like to include some other historical objects. As poets are wont to do, I will wait for synchronous moments to come – I know these material stories will make themselves known to me.

This is part of a journey and Mike Hurst, along with his film-mate Andrew Chung, and Tim Page are the guerilla film / photo crew capturing formative moments in order to make a lovely documentary – more on that later!

I guess this is a round-about way of also addressing the question: ‘What does it mean to be a Pasifika Poet Laureate?’ It means doing this stuff. Taking the Laureate-ship along in my Pacific-infused life (we are, after all, in the middle of the Pacific), not just in incidental ways, but in deliberate, epistemologically-informed ways that centre Pacific worldviews, at least, as far as I see and experience them in my life as a Pasifika poet-scholar.

So, as the Poet Laureate, people matter to me, stories matter to me, especially when those stories have existed on the margins of mainstream consumption. Creativity and freedom matters to me, honoring my own unique poetic voice, and continuing to grow it matters to me. I have two years to work on these things that matter to me: to continue taking poetry ‘to the people’ and to continue growing poems!

We are about to step

on stage at Aotea Centre

in front of a sold-out

crowd of two thousand

I ask

How would you like to walk on –

before me or after me?

You say

Let’s just do this

and take my hand.

We stroll on

side by side

to a standing ovation

your hands become doves

from ‘Alice Walker’ in ‘Queens I Have Met’

Auckland University Press page

Poet Laureate blog

NZ Book Council page

Watch Selina perform ‘Unity’ at Westminster Abbey here

Gina Cole picks ‘In Creative Writing Class’

‘The Dogs of Talimatau’ at The SpinOff

Selina picks Tusiata Avia’s ‘This is a photo of my house’

Ordinary Time Victoria University Press, 2017

‘I want a little quiet, a piece of the day

where the baby and I soak in our own silent language.’

from ‘Speech and Comprehension’

Anna Livesey has published two previous poetry collections, Good Luck (2003) and The Moonmen (2010). She graduated with an MA in Creative Writing from Victoria University and was the Schaeffer fellow at Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2003. Her new collection, Ordinary Time has just been published by Victoria University Press. With these new poems, personal experience is paramount because this book, with its roots and wings in the miracles and challenges of parenting, is an intimate exposure. Lines are agile, things pulse, gaps pollinate, and the glorious, challenging, curvatures of motherhood are brought searingly close.

The interview

Paula:

‘Having not been out for days I have very little to add—

save that the house is sweet and clean, the baby safe and fed.’

from ‘Synthetic Thinking’

Before I enter your new collection of poems, I stall on the title: Ordinary Time. Poets have often used ordinary things as a gateway to the less ordinary, as a way of refreshing little patches of the world about us, whether experience, sensation or physical object. Yet the title goes deeper for me, particularly having read the word ‘parenthood’ in Jenny Bornholdt’s quote on the back cover. It feels like you are boldly staking the domestic space and the mothering role as a necessary and fertile springboard for writing. How does the title resonate for you?

Anna: One of the things I think about a lot (for whatever use it is), is our moral responsibility to the world we live in – who we should care about, who we should care for. What events – horrors and wonders – should we allow to get under our daily carapace and work on us? Especially in this world where the news of disaster is never far away. There’s that phrase about extreme weather events: “the new normal”. Hurricane Irma – the new normal. Degradation of democracy in the States, Spain, parts of Latin America where it was once thought it be bedded in – the new normal. The end of Francis Fukuyama’s “the end of history” – the new normal.

The book starts with Peter Singer, a moral philosopher who basically says – “we are all equally valuable so we are wrong to value ourselves, our families, our tribe above those who are ‘other’…”. And I believe that, but I also believe it is an impossible and inhuman doctrine. To me this is the puzzle at the heart of this book and the title. My beautiful, blessed, mundane life of glorious domesticity and early motherhood with my children, husband, friends and family and warm dry house with full cupboards exists in the same reality as Syria. Where children as beautiful and as beloved as mine are dying. Both of these realities are “ordinary”.

To survive and function and care for those who are most immediately our responsibility we need (or at least I need) to take refuge in the shared human mendacity of closing up our carapace and giving an emotional shrug. And in fact I think this is not really the “new” normal, but just normal – the Hobbesian description of the human condition – “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short” – continues to hold true. (And as I type this I think – and what is the point of poetry in all this anyway?)

And then on the other hand – the title poem talks about the late winter time when the magnolias all around Auckland are covered in their magical flowers. They look like aliens or supermodels, all lanky grace and outrageous decoration. Then the flowers fade and the “green leaves of ordinary time” appear and the magnolias just look like normal trees for another year. So yes, the title is also a nod to the magic and mania of those first early weeks with a new baby, and how they refine and change one, as a parent and inevitably as a writer.

‘(…) Across the road two magnolias, one pink, one white. In the days

since we came home I’ve watched their stark flower-spiked branches

soften and go pastoral—the green leaves of ordinary time climbing out

of the wood.’

from ‘Ordinary Time’

Paula: That nagging doubt about the value of writing poetry is a tough one. What difference does it make to the Syrian crisis, the ordinary families there that love their babies, eat, sleep, celebrate and mourn? Perhaps one response is that in translating your experience you contribute to a global poetry conversation that opens windows on how we live with our different hungers, failures, connections, kindnesses.

‘I am a person in love with nostalgia

and this unfits me for every moment of living but the one just past.’

from ‘I Am a Person in Love with Nostalgia’

You record the early weeks of motherhood and the poems undulate through fatigue and joy, routine and insistent questions. I love the way you pull things from the past into the patterns of the present. I particularly love ‘I Am a Person in Love with Nostalgia.’ It feels like there is nostalgia for former selves, but you also make a precious baby moment glow that might be a future nostalgic memory hub. What kind of returns does poetry represent for you?

Anna: The returns of poetry. Let me first be contrary and take returns in the sense of “what you get back”. In my previous book, The Moonmen, there is a poem called “Bonsense”. Bonsense means “good sense” – ‘bon’ as in the French “bonne”, for good (and indeed the Scots “Bonnie” – beautiful, cheerful – which is my daughter’s name). The poem is about the returns of poetry, and of art, the non-essential, in general. It is addressed to a dear poet friend who had a job caring for a very very small library in a small town in Montana, and ends:

“From the chest of your books

you enjoin belief

in outposts of minature sense or nonsense,

or going further, antonym, bonsense—

the elaborate folly of the heart and brain,

built curlicued, baroque.

What bonsense is this, a tiny horse, a tiny library?

The great iced cake of relationships,

the ornamental pony of compassion,

the perennial shout (SHOUT) of shared exclamation.”

The central idea here is that compassion and art spring from the same core impulse. Imagination/transportation/identification/recognition/the marvellous… these are human characteristics and lead to our greatest baroqueries – the welfare state, poetry, breeding horses too tiny for any purpose but to be admired. I don’t feel that poetry needs to “do” or “contribute to a conversation”. I think the return of poetry is merely for it to be.

And the returns in the sense of nostalgia. Every time I have published a book I have felt a part of myself caught in amber. And through my three books the amount of “me” that is there like an insect in the settled gum is greater than before. And in this book, as you observe, “me” has expanded out and encompasses my babies. As I am writing this to you, it is day one of Bonnie being fully weaned. Yesterday she had her last ever feed and five years of being pregnant, breastfeeding or both came to an end for me. So to have that moment at the early cusp of our relationship captured and kept in a way that I love, that moves me back into that moment perfectly, is infinitely precious. A memory outside myself. That is the personal return of poetry.

Paula: I loved that. For me, it is exactly why poems that venture into the domestic or the personal are utterly productive for reader and writer.

‘When my mother died she had spent

a long time in darkness.

When my grandmother died she had spent

a medium time in darkness.

When my daughter was born she had spent

a short time in darkness.’

from ‘Quotation’

That phrase ‘caught in amber’ really resonates, and that poems can be an intimate way of catching a present moment to savour the future. Is there a poem in the collection that particularly resonates with you? I found myself haunted and, as that word rightly implies, returning to ‘Quotation’. I was entranced by the generations of women and by the distinctive dark and light.

Anna: That’s like asking if I have a favourite child! I’m pleased you asked about “Quotation”. It’s a funny little poem – the opening lines include a quotation from William Calos Williams, of course — “Danse Russe”. In that poem, Williams is talking of himself, dancing naked, singing (go and read the poem now…! Such an image it is), waving his shirt around his head. His poem ends “Who shall say I am not/ the happy genius of my household?”. My grandma was a brave woman (a WREN, among the first five WRENS to be choosen to go on a troop transport as decoders), but also a modest, genteel, English/Irish Catholic of her time. And so the image of her secretly dancing naked, admiring herself as Williams does, is part of the joy of that poem for me. And then there is the word “genius”. In my poem, as in Danse Russe, it means, essentially, “the soul of a place” – the genius loci, the ancient Roman concept that all places have a soul. So my poem is saying… who shall say that this modest woman, looking like a snuggly grandmother to me, her little grand-daughter, was not in fact a wild dancing creature, the secret, gleeful soul of the old farmhouse.

And then I just miss her so. And the farmhouse that had every aspect of a fairytale farm – my Grandpa made all the bread, there were hens and herbs and a sheepdog, a shy white cat, treasures from India (war service), a dressing table with mirrors that folded out and could be made to reflect themselves into infinity. Winegums in the pantry for story time. Easter in the garden. Woollen blankets. Grandpa’s blue farming overalls. Sunday roast – “from our own sheep”. I want every single part of it back, including and especially them.

(I should note here my family have a terrible weakness for writing books. My mother was a published historian with several books to her credit. My Grandpa wrote several local histories of the Wairarapa and a five volume self-published autobiography (Yes. Five volumes. And very interesting they are, at least to me). My grandma trained as a speech teacher in her 60s and then wrote plays which her students performed in the garden at Perrymead. She also wrote short stories for us, her grandchildren, and several of them were read on radio. So I am not just missing the rural idyll and the unstinting love of Grandparents, but also missing a formative place, where books and language and storytelling and performance were part of everyday life.)

In this poem, and in ‘Privacy’, and several other poems in the book, I was thinking about a passage from Simone de Beauvoir’s memoir of her mother’s death, A Very Easy Death. In the book she is looking for keepsakes for her mother’s friends, after her mother has died. She writes: “Everyone knows the power of things: life is solidified in them, more immediately present than in any one of its instants.” (C.f. Williams: “no ideas but in things”). So that’s the desire behind taking their house and putting it in my house — I want to “quote” their life in my life through their things.

The poem ends with another quotation, from Yeats, “John Kinsella’s Lament for Mrs Mary Moore”. Again, if you don’t know the poem, go and read it. It’s a song of grief for a witty, wise, sexy old woman (I have always loved this poem and it continues to appeal as I grow a little older myself and hope to be appreciated in the round, (even and despite my flaws), as John Kinsella appreciates Mrs Mary Moore). The repeated refrain is “What shall I do for pretty girls/ now my old bawd is dead?”. Mrs Mary Moore is, literally, a bawd. And so again this is a naughty joke on my part. My grandmother was a witty, wise, sexy older woman. She absolutely die to see that written down! But I love having that thought about her.

Paula:

‘is this how my mother felt

this fear, this,

bewilderment?

I want to mother better than I was mothered.

I can say this because she is dead.’

from ‘Bay Leaves’

I like the idea of a poem as keepsake. A way of preserving familial relations in the manner of a photograph album, a daily journal or a shoebox of mementos.

The collection offers myriad rewards for the reader. It is a bit like peeling back layers of living to expose the challenges along with the miracles or joys. I am drawn to the way the world rubs into the private life: the child washed up on the beach makes the mother hold her child that much closer. Perhaps the poems that struck deepest faced the mother, the mother no longer here, the mother who prompted the poet to look at her own mothering. Were these difficult poems to write?

Anna: No they weren’t. The difficulty was in the long years of decline. My mother was a writer, so writing feels like a very real way to honour her. Making art felt like salvaging something.

Paula: Do you think, in this move to the overtly personal, other things such as musicality, changed a little too?

Anna: I deliberately wanted some of these poems to be clumsy. Awkward subjects deserve an awkward sound. That’s not something I would have been comfortable with in my earlier work.

Paula: Were you tempted to include endnotes as some poets do? I can go either way. Endnotes open up poems in ways I don’t necessarily anticipate, adding avenues of delight, but conversely might limit my own freedom to explore and delve within the myriad possibilities of a poem.

Anna: My first book, Good Luck, had endnotes. There was a lot of found poetry and I wanted to reference where it had come from. With this book I thought about end notes, very briefly. And then I thought: who has the time??? And also I didn’t want to explain the poems – either they do their own work or they don’t.

Paula: Did you read any books while writing this that affect how and what you were writing?

Anna: Czeslaw Milsolz’s Roadside Dog – a little book of prose poems, limpid, narrative, engaged, straightforward, complicated, personal and full of the world. The best bits of Ordinary Time are really just a crib of Roadside Dog. Raymond Carver – again, the direct voice of his poetry. The beautiful poem, “The Haircut”, of his referenced in “Because I’m a Human”. Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life is the book that “Reading Books About the War” lifts off from. Tove Jannsen, the Moomintrolls – moments of recognition in literature affect me profoundly, especially when they are parent/child, and Tove Jannsen does these so beautifully. I am always reading Janet Frame’s poetry, and hoping for a little of her perfectly awkward insight to rub off. And then also the manuscript of my dear friend Lauren Levin. Her work is quoted in the last poem in the book. She has just had a truly wonderful book published – The Braid. If you care about poetry and about women and about the world and about justice and about beauty you should order it. And Heather Tone’s Likenesses. There are several poems for Heather in The Moonmen, and she and her luminous, curious, outsider-mind writing are a constant inspiration to me – how to live, how to write.

Victoria University Press page

Flow: Whanganui River Poems, Airini Beautrais, Victoria University Press, 2017

Airini grew up in Auckland and Whanganui, studied both ecological science and creative writing at Victoria University and has worked as a science teacher. Her debut collection, Secret Heart, won Best First Book of Poetry at the Montana New Zealand Book Awards in 2007. She has also published North Western Line and Dear Neil Roberts.

To celebrate the arrival of Airini’s fourth poetry collection, we embarked on an email conversation over the course of a week.

Paula: After reading the first few pages of your new collection, Flow: Whanganui River Poems, I felt the kind of spark that travels like electricity through your body as you read: heart, mind, ear, eye, everything on alert. When I was doing my Masters in Italian I read the fragmented fiction of Gianni Gelati. His writing was poetic, strange, addictive. With Narratori delle pianure (Storytellers of the plains), he travelled the length of the River Po, collecting stories from people who lived there. His people, his river, yet while the river dictated the itinerary, it was less of a protagonist. Instead the people he met flourished on the page in their out-of-the-ordinary ordinariness.

I had the idea at page 24 of Flow to have an email conversation with you as I read. I wondered how my relations with the poems might change over the course of reading; the reading would act as my surrogate river with its various currents and tributaries. I wondered how I would shift in view of the poetics, the ideas, stories, characters and the river itself. The book fills me with curiosity and delight at what poems can do.

My first curiosity. How did you prepare for the river poems beyond the craft of writing? Did you travel the river, visit communities, trawl the archives or rely on memory and books?

Airini: It’s interesting to hear about Gelati’s writing. In my case, I couldn’t say ‘my people, my river’ because I’m Pākehā, and the Whanganui is definitely a Māori river. My connection with the river is different. I see it often – I drive over it at least twice a week – but it still has this sense of mystery about it. I’ve never travelled the middle reaches, although one day I hope I will.

When I began writing Flow I had two preschoolers. It was tricky to get out and about, and I was writing/ researching in short bursts while they slept, or during minimal crèche hours. I did do a little bit of travelling, which is depicted in places in the book (poems like ‘Confluence’, ‘Tributaries’ and so on). I read a lot of local histories. I read Waitangi Tribunal reports. I visited museums and galleries. I talked to a few people, but I generally feel quite uncomfortable about the prospect of interviewing someone for a poem. Also, some of the people I contacted never responded – the whole idea might have sounded too strange. There are some of my own memories in there too. When I was twelve I went on a trip with my family’s church (Quakers) and we visited a number of the marae along the river. We were guided by Morvin Simon, who passed away in 2014. That trip made a lasting impression on me. A few months later the occupation of Pākaitore happened, and we went down there to support it. There’s a villanelle in Flow called ‘Pākaitore’ about the day the police came to arrest the protestors and a group of people held hands in a circle around the park. At my book launch, local Quakers and Treaty workshop facilitators David James and Jillian Wychel told me that in fact there hadn’t been quite enough people to stretch right around, so the poem exaggerates things. I feel like that’s acceptable, in a poem. It goes for the sense of a story rather than the cold hard facts. I think all histories do this to some extent.

Paula: I was thinking about the fertile relationship between history and poetry when I read the first poem, ‘Confluence’. It seemed especially apt that the merging of two rivers also conjures the coming together of voices from the past in the poems to follow: Māori or Pākehā, a farmer, a surveyor, the surveyed.

Standing at the confluence

you can see the join in the rivers; either side

a different colour and speed.

Like standing at Cape Reinga watching two oceans

seam together.

from ‘Confluence’ (21)

Exaggeration can intensify a scene, but as I am reading, it also feels like I am reading some kind of truth. The representation of history produces multiple contesting truths, myriad confluences. Did you develop ‘how you represent history’ as you wrote? Did faithfulness or truth play a part?

Airini: I think we can only ever write an individual version of events, when it comes to history. We all come with our own interpretations. What happened happened, and there are things that are non-contestable. But how we approach these things in writing is something a little different.

I knew from the outset I couldn’t attempt anything like an authoritative history. It wasn’t my place to do that. I wanted to weave together lots of different threads, like the many tributary streams of the river. I also wanted to write something polyphonic, so I incorporated lots of different voices from different times and places. Some of these are inanimate objects talking – a fence, a shipwreck, a playground dinosaur. This is, of course, far from the ‘truth’ in the conventional sense. There are episodes I’ve narrated in the first person, from my imaginings of what it might have been like to be present. The Ongarue Rugby Club really did stage Antony and Cleopatra in the 1950s, and that just seemed so incongruous to me, but also so appropriate, that I wanted to imagine myself there. There are voices in the collection that are entirely made up, and most of them are female. The historical record is a record of privilege, and it’s largely male and largely Pākehā. Early on, another woman writer commented that most of my characters were male. I thought ‘shit, they really are,’ and the process of writing women in began. Some of them are based on real people and some of them aren’t. Some are myself and some are alter-egos.

Paula: That we enter the voices of the river, and that those voices are no longer dominated by the authoritative status of mainly white men, is exactly what makes the collection so absorbing. On the inside blurb, James Brown asks whether ‘verse is the future of history?’ For me, I got transported, as though on the river currents, by voice; not so much fact and not so much analysis but by way of immersion in time and place. I guess fictional narrative can also immerse you in an historical elsewhere, but poetry does it without plot momentum, character development.

In the first section of poems, ‘Catchment’, I got a strong sense of voice housed within poetic predilections of the past. I got an ‘air’ of Jessie Mackay and Blanche Baughan, with ballad-like rhythms and spine-like rhyme. Yet the poems are not exact replicas of early settler poetry; there is a different kind of economy, line length, degree of description and sentiment.

Did you read some of our early poets to infuse style of writing into place and voice? Particularly the women?

Airini: Yes, I did read some colonial poetry, including Australian poetry. Unfortunately for my purposes, a lot of it is also by, and about, men. Blanche Baughan’s poem ‘The old place’ was one that was floating around in my head. I knew I wanted to evoke the ballad tradition because I thought that if these pioneer ghosts talked in poetry, that would be the form they would choose, the form they’d be familiar with. I wanted there to be a sense of these ghosts in the book. Then again, there are some other four-line forms in the first section, ‘Catchment’, which aren’t traditionally associated with settler poetry – like the Sapphic stanza. I used that in a few poems with female narrators. It’s a very feminine and very emotive form. I’d read over and over that it was impossible to approximate classical quantitative metre in English, because English is a stress-timed language. But then I wrote these things and performed them and something strongly rhythmic came out and took me by surprise.

With the ballads and Tennysonian and Keatsian stanzas there’s an element of pastiche, but I also wanted to push beyond that. I think when traditional or inherited forms are mixed with more contemporary diction, points of view and so on, there’s tremendous potential for language to be stretched and to be weird, which is something I strive for in writing poetry.

Paula:

The first snow falls

like sugar, sown

breath-thin

on each blank mountain’s face.

The rock

pricked

apart by needling ice

like shattered bone

bears

down, and wears

down to fine scree.

from ‘Snow’ (80)

I think the playful pastiche of form and diction produces another hallmark of the book: its musicality. I was thinking this is history as music with various chords and keys, rhythms and aural densities. Did you listen to music as you wrote? When you perform the poems is the musicality significant?

Airini: I don’t listen to music when I write, because I find myself focusing on the music too much, and being distracted from what I’m trying to write, or having the emotion of the music trick me into thinking what I’m writing is moving or meaningful when it might not be. The ‘music’ in the poems is probably mostly due to the use of forms that derive from song lyrics. The poem you’ve quoted, ‘Snow,’ is modelled on a song by the troubadour Arnaut Daniel, called ‘L’aura amara’ (The bitter air). I owe a debt to Ezra Pound’s translation here. It’s a love song, but I felt the tone of loss and longing was suited to a poem about a damaged landscape. I’m really interested in complex and repetitive rhyming forms, and how the form shapes the material. The history of the lyric is a fascinating one – that poetry has its roots in music, but there’s been a divergence of the printed word and the song. In some ways it’s a great loss for poetry, but on the other hand there are different possibilities opened up by the page, and the lyric tradition can feed into these.

Some of the poems in Flow could probably be quite easily set to music, particularly the more rhythmic forms. There’s one in particular, ‘Surveyor’s grave,’ which I always hear in my head with a tune. But when I perform the poems, I just read them.

You couldn’t wield a pair of secateurs

to save yourself. And what use is a man

of unsure grip? But still, that soft hand-span

enters my thoughts, down where the ocean blurs

the land, repeatedly. The hot sand stirs

under our feet; we climb to where the tan

of pīngao, grey of marram holds what we can

be held. We’re silent, and the wind concurs.

from ‘Gathering the berries of Pimelea turakina’ (162)

Paula: Oh gosh I love the idea of Flow performed to music – the whole thing. I also love the idea of ghost forms hovering behind the poem as I read, and the way the musicality of form is like a set of lungs, stretching and receding, stretching and receding, with replenishing oxygen, over time.

I walk the baby to sleep along the bank,

among the disposable nappies, circles of bourbon bottles.

Tea from a thermos, talk of our grandparents.

I’ve bought Joe a kilo of frozen peas, to take a fish north.

from ‘Confluence’ (22)

At the start of the book a baby is being walked by the river, your baby perhaps. In my readings of New Zealand women’s poetry across the past century, for many women, but not all, writing poems fits into domestic spaces. Life intrudes and disrupts and nourishes writing. Do you think it makes a difference that you are a woman writing Flow, a woman with a family? You talked about gathering and inventing the voices of women as a counterpoint to the privileged men. How else might it matter? Or change things?

Airini: It makes a huge difference that I’m writing as a woman, and as a radical feminist woman. It makes a difference that my ‘domestic spaces’ during the writing of this book were not supportive or safe, and that by the time it was published I was re-negotiating life as a single parent and as a survivor of intimate partner violence. Writing was an act of resistance on a political level, on an artistic level, and on a personal level. I managed to write because I had a supportive extended family, particularly my mother, and I had a strong network of writing colleagues, many of whom were also women and mothers. It’s 2017 and amazing things have happened over the last century, but I still think there’s a battle involved in women’s creativity that men don’t experience in the same way. Children and child-rearing complicate this picture further.

Then there was the wonderful support of my two PhD supervisors, Harry Ricketts and James Brown, who nourished this collection from the first tentative drafts through to the final cut. I have immense respect for both of them. Our three-way conversations always felt friendly and collegial, and I feel lucky to have had this mentorship.

It’s hard for me to step back and look at the bigger picture when I’m working through the issues, but I feel that there’s so much work to do at every level, from global to individual. New Zealand women’s writing is flourishing, but there’s a way for us to go. It still feels to me like there’s a dominant maleness in our literature, which comes through in reviewing, in prizes, awards and grants, and in who we revere. What I would like to see are networks of supportive communities, where all the barriers of privilege are broken down. We live on islands and we have to find ways to work together.

Paula: It makes huge difference to me too. So far we have had five women out of fifteen Poet Laureates! The question, though, is why I am writing a whole book on New Zealand women’s poetry. I have just been writing a section on Robin Hyde and Joanna Margaret Paul – both produced poetry that was deemed too hysterical or too feeling-indulgent by men. I strongly disagreed. In fact I felt quite wrung out writing the piece, knowing that women’s writing still gets denigrated for domesticity or feelings or departure from a provisional (in my view) paradigm. I actually felt both women, and I am sticking my neck out here, wrote to counter the dark of their lives, not replicate the dark.

Reading Flow as I wrote about their poetry was so satisfying. The sumptuous choral effect produces so many layers, it is a book that demands multiple attentions. I love the fact I can’t leave this book yet. I need to spend longer with it.

Is there a book of New Zealand poetry that has had a profound effect upon you in the past year or so?

Airini: I’m happy you mentioned Joanna – she was a family friend and a great inspiration to me. Living in Whanganui, I often wish she was still around so I could drop in for a cup of tea. At the launch of Flow, Jenny Bornholdt read one of Joanna’s poems, ‘Blue Fleur.’ It meant a lot to me to acknowledge the work of those who’ve gone before. One of the things patriarchy does is pit younger women against older women or women of the past, like ‘You’re hip and sexy and we like you, but we don’t like her, she’s stuffy and old fashioned.’ This isn’t, of course, confined to poetry. But I think as women writers we have to find women role models as well as, or in place of, men. Joanna is someone I think of as a quiet trailblazer, an amazingly self-assured and independent woman, who lived her life, did her own thing and made the art she wanted to make, without being governed by the approval of the establishment. I think of Jenny as someone who has in part continued and extended Joanna’s poetic projects.

There have been lots of books that have affected me this year, in lots of different ways. One that stands out is Cilla McQueen’s In a Slant Light (Otago University Press). It made me laugh and cry. It’s written in a simple, often prose-like style, and the weight of it is absorbed almost subconsciously. I was moved by reading about Cilla’s journeys through motherhood, relationships, work and life, to creative success. It’s the story of a woman doing creative work against the odds. There’s a familiarity about a lot of the material, but also the differences that come with time, place and other circumstances. Reading her story gives me strength.

Paula: In my chapter on Joanna, I also said I would like to have tea with her and talk poetry! I think there is a strong community of women poets across New Zealand with different kinds of support. Michele Leggott, our first Poet Laureate under the National Library, continues to shine a light in the shadows so we may see women writing in the past. Sarah Jane Barnett, literary editor at Pantograph Punch, devotes significant attention to what women are doing. And I was delighted to see Selina Tusitala Marsh appointed as our new Poet Laureate. I see her becoming as beloved a national poetry icon as Sam Hunt and Hone Tuwhare.

I also loved Cilla’s memoir and was disappointed that a number of the reviews felt it missed the mark in terms of the life it revealed. I loved the way it showed, in poetic form, with as much white space as it desired, a woman coming into being as both poet and mother. Just as in Joanna’s poetry, the hints are there.

Were you tempted to use ‘Endnotes’ to signpost the layering of the poems? I can go go either way on this. I actually liked the fact there were none because it means the poem will linger and haunt me with possibilities for longer. On the other hand, a road map does satisfy curiosities and can send you in new and unexpected directions as reader.

Airini: I thought about notes, and I also thought about a timeline of events. In the end I decided against it because I thought it might over-explain things, or be something readers just skip. There’s a common idea that we have to explain ourselves in a notes section, or people might not know what the poems mean – I’ve done this before, I think most of us have done it. In this case, I wanted to let the poems stand alone, and retain a sense of mystery. I thought of them as being like objects washed up on a beach: some are identifiable, some not. I have included a selected bibliography of my main print sources so that anyone who happens to be interested in regional history can go and check it out for themselves.

The maps in the book give a visual indication of where things happened. These were kindly made for me by my brother Joe, who’s a geographer. While I was writing, I spent a lot of time looking at maps. I’d get an old topomap or a park map and spread it out on the floor and pinpoint the places I was writing about. I drew sketchmaps of the region and of where the poems fitted in.

I hope that each reader will bring their own interpretations to the work. I don’t think one always has to know exactly what’s going on, in order to enjoy a poem.

Paula: For me, that is one part of the pleasure in reading the collection. It is a bit like reading Bill Manhire’s glorious Tell Me My Name. I don’t know when I will ever check the answers to the riddles at the back. I love the mystery, the lure of the gap.

This collection formed part of your doctoral thesis. What did you navigate in the academic piece of writing?

Airini: I wrote about narrativity in long poems and poem sequences. By ‘narrativity’ I mean the extent to which a text is narrative, or, does it tell a story and how might that story satisfy conventions such as plot, character etc. I focused on how sequences are divided: into sections, poems, stanzas, lines, units of metre, and so on. I was looking at recent poetry by Australian and New Zealand writers, like Dorothy Porter, John Kinsella, and Tusiata Avia. I argued that the division into individual poems was the most significant in terms of narrative. This division allows the poet to make abrupt shifts in chronology, geography, between points of view, and so on. These shifts can support narrative or undermine it. There have been a lot of poem sequences written over the last century with a decidedly anti-narrative bent. Then in the last few decades we’ve seen a revival of the novel in verse, which often falls back on traditional narrative conventions (albeit juxtaposed with the departure from convention that comes from writing in verse). I think Flow falls somewhere in the middle of the spectrum: it’s not a single plot-based narrative but there are strongly narrative elements in it. I’m not trying to be wilfully incoherent, but I’m also not trying to attempt an exhaustive history with a chronological structure.

Paula: Was there an anecdote or voice that particularly surprised you – either in the finding or the invention?

Airini: There were lots of surprises. There was material I wasn’t expecting to include that I couldn’t let go of. I wanted to write a poem about my children playing in the river mud – which they do reasonably often. Then I read accounts by elders of growing up at Kaiwhaiki and learning to swim in the river almost before they could walk. And I stumbled across a story about a pregnant woman who drowned her four-year-old child in a high flood. This particularly haunted me. The three stories are quite separate but they came together in a poem called ‘Three mothers.’ I probably won’t ever read this one aloud because I can’t read it without crying. I think every parent has had moments of utter desperation and darkness, and we respond to those times differently, but it’s possible to see how things can go wrong in difficult circumstances. I put these stories together to reinforce the idea of interconnectedness in our lives – past and present, in bad times and in good.

The pang, the push, the slide,

the stretch, the yawning wide,

your supple form uncurled

into the waiting world

and water was your guide.

from ‘Children in the mud’ (122)

Paula: I love that poem! I think there is river-like coherence and momentum in the collection which is built on story. What animates the reading, is the interlocking sense of a provisional whole, and the gleam of the small pieces.

I was thinking, as a way of concluding our conversation, we could each pick a poem from the book that particularly resonates. Does this change when you pick a poem from the page and a poem you have favoured on your tour?

The book runs to almost 180 pages so there is such an array of poems to choose from. I have greedily decided to assemble a tasting plater of some of the poems I love.

In the first section, one poem, ‘Final whistle’, kept pulling me back, maybe because it doesn’t play with rhyme as the others do, so aurally it breaks the sound arc. But it is like a three-dimensional snapshot of emptiness: the landscape denuded along with the men, the weather taken over human activity. My partner spent part of his childhood at Te Wera, his father running a forest. We went back to visit and saw the the village was like a ghost village. As we walked up to the shop at noon, the owner was turning the sign to CLOSED. He said it was for the last time. Their stories then rang out across the valley. It seemed so melancholic.

(…) Well, I don’t know

why I am crying,

thinking of the bush and its eerie sadness,

rain collapsing all of the things we made here.

Still, I know they’ve sawn every dip and ridge, left

nothing of value.

from ‘Final Whistle’ (63)

I loved the rich, pungent detail in ‘Seed’, its list-like qualities and the way it also becomes song as you read.

You are in the wildness, wild with song and honey.

You are the beak and tongue and claw.

You are in the rock face, weathered by the freeze-thaw,

in the summit sulphurous and stony.

from ‘Seed’ (82)

Repetition is such a drawcard for me – it evokes the river current but also the currents of history, personal lives, stories being shared. I especially like it in the title poem, ‘Flow’, with its rippling rhyme.

To the stone, to the hill, to the heap, to the seep,

to the drip, to the weep, to the rock, to the rill,

to the fell, to the ash, to the splash, to the rush,

to the bush, to the creep, to the hush

from ‘Flow’ (84)

The river often finds its way into the poems aurally and visually. In ‘Map-making’, I love the white space that cleaves through the middle of two poems like the river.

The chain clanking, the clouds closing

we waded through wetness. Wastex is the word for it.

Feeling each footfall, scenting the foetid

slurry of shrubbery sliced with the slasher.

The fog had a freshness I felt through the flannel

cloth of my shirt: it clung to me, clammy.

from ‘Map-making’ (88)

‘Shingle beach’ is resembles a song two keys; it reminds me of the way the beach is always in a state of flux. When you visit every day you get to know those moving sands and lights. This is the second stanza:

To even out

to open space

the stone removed

its roundness cracked.

A straighter course

a blotted spill

a metalled road

a deeper hole.

‘Shingle beach’ (90)

Some poems are luminous with sensual detail; they are a bit like establishing shots for the narratives and voices the precede and follow.

Wet tang of sheep shit, mass of trees

releasing plant-scents in the angled sun,

those smells of summers been and gone,

bruised sap, ripe humus, rising to the nose.

from ‘Kauarapaoa’ (120)

If I had to pick one poem, though I would pick ‘Pour’, the penultimate poem in the collection. The poem tips out a list of similes that snap on the line; then when you get to the end there is that sweet echo, mysterious, ambiguous, gloriously fertile. Here are the last three stanzas:

like a steamer stack

like a sudden break

like an afterbirth

like the restless earth

let it all pour out.

Let it all pour out.

from ‘Pour’ (176)

Airini: The poem I’d like to pick is ‘Plotlines’, which is kind of meandering, but sums up the main preoccupations of the project. It also links to what I was thinking about in terms of narrativity. I’ll quote the last two stanzas:

My son always wants a story. Tell me a story about a T-rex

who was far away. Tell me a story about a spider

who was lonely. And if the plotline doesn’t develop:

‘That wasn’t a story! I want a proper story!’

Obstacle, obstacle, obstacle, solution.

Even a three-year-old knows the basic devices.

Obstacle, obstacle, obstacle, attempted solution, failure.

The greatest stories of all time are geological.

from ‘Plotlines’ (23 -24)

Victoria University Press page

VUP interview with Airini

Emma Shi’s review of Flow

‘Flow‘ in Overland Journal

For the complete interview see here.

Jonno Revanche: One of the things that stands out from your poetry collection is not just how funny it is, but it’s a very precise kind of humour, one that allows for introspection, sentimentality and emotional involvement. For example, in ‘mirror traps’ you declare it’s ‘love that plummets you down the elevator shaft.’ Sort of blunt, but still honest and witty in its own way. Do you find it hard to accommodate all these things? If so, do you feel like it took a lot of practice to get there?

Hera Lindsey Bird: This is a hard question to answer because it’s so second nature to me now, and I don’t mean to sound like I’m dashing off poems while laughing in a stolen Cadillac, but that particular hybrid of humour with a base of emotional honesty or engagement is almost all I care about in writing these days. There was a period when I first started, and I was writing a lot of controlled, aesthetically rigid poems but I quickly became bored of that, and when I get bored I get reckless, and when I get reckless I send a lot of joke poems about oral sex to my masters supervisor. But most of the work was admitting to myself what kind of writing I truly had the energy and enthusiasm for, and giving myself permission to write that way. My favourite writers in every genre always straddle the line between comedy and emotional engagement, George Saunders, Chelsey Minnis, Mark Leidner, Frank O’Hara, Lorrie Moore. It was just a matter of admitting that to myself, and then hot-wiring Cadillacs became a lot easier. I never write well when I’m sombre. Even my greatest personal tragedies I like to turn into a joke, which might be a personal failing but I don’t think has been a poetic one at least.

The Starling Issue 4

Ok, I am a big fan of this.

This is an excellent issue. Featured writer, Chris Tse’s poems are rich in direction and effect.

Most importantly, the editors are adept at selecting fresh young voices that make you hungry for poetry (and short fiction ) and what words can do. I was going to single a few out – but I love them all! Eclectic, energising, electric, effervescent.

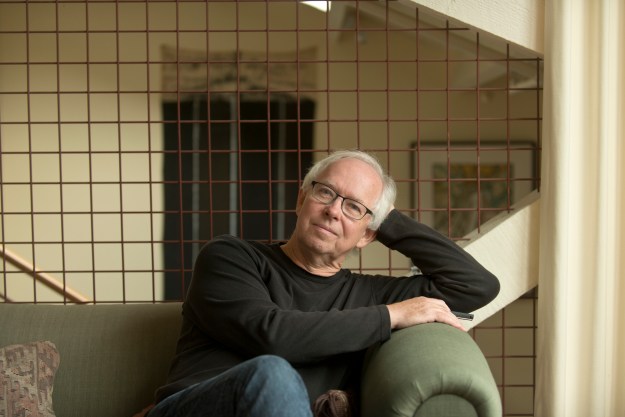

Bill’s interview is a good read:

On rhyme: ‘On the other hand I think sound patterns are at the heart of poetry – they tug words away from meaning and towards music. And one bizarre thing is that the need to find a rhyming word can force you to move in directions you might not have otherwise imagined. Rhyme can make you surprise yourself.’

On needing a dose of humour: ‘The greatest danger for poets is self-importance. Some poets really do believe themselves to be wiser and more perceptive than the rest of the human race.’

On getting students to bring poems by published poets to share in class: ‘The main thing would be that no one in the class would have their minds made up beforehand; or be trying to bypass the poem in order to find out ‘what teacher thinks’. It’s much better for the students to bypass the teacher and get to know the poem directly. Paradoxically, a good teacher can help this happen.’

Elizabeth Smither with Rusty and Sneaky

‘The Labradors have made nests already

simply by lying in the long grass

sucking the green into their bodies’

from ‘Lying in the long grass between two black Labradors’ in Night Horse

I recently read through the alluring stretch of Elizabeth Smither’s poetry; from Here Come the Clouds published in 1975, to the new collection, Night Horse, just released by Auckland University Press. I was drawn into melodious lines, pocket anecdotes, bright images and enviable movement. Harry Ricketts talked about the transformative quality of Elizabeth’s poems in an interview with Kathryn Ryan, and I agree. As you follow reading paths from the opening line, there is always some form of transformation. The poetry, from debut until now, is meditative, andante, beautiful.

Elizabeth Smither has written 18 collections of poetry, five novels, five short story collections, journals, essays and reviews. She was New Zealand’s Poet Laureate (2001-3), was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Poetry in 2008, the same year she received an Hon D. Litt from Auckland University. She has appeared widely at festivals and her work has been published in Australia, USA and UK.

To celebrate Night Horse (Auckland University Press, 2017), Elizabeth agreed to answer a few questions.

‘You can run as fast as Atalanta

who bowled three apples at her suitors

Double Red Delicious’

from ‘An apple tree for Ruby’ in Night Horse

What sparked your imagination as a child? Was reading a main attraction or did you also write? Did particular books endure?

Reading and writing. I liked to say long sentences to myself as I walked. The first thing I can remember writing about was my pet New Zealand White rabbit. All the usual books of the period: Anne of Green Gables, Little Women, A Girl of the Limberlost which I found faintly terrifying. I can see these are the precursors of George Eliot and Jane Austen. As a teenager I had a crush on French writers: Colette, Gide, Mauriac, Sartre, de Beauvoir, Simenon. My father was a great novel reader and he impressed on me the sacrifices made by writers like Charles Dickens. I was scared of Quilp in The Old Curiosity Shop and never got past the page on which he appeared.

‘The cats are out by the letterboxes

at the ends of long driveways

waiting to see how the night will shape itself.’

from ‘Cat night’ in Night Horse

Your debut poetry collection, Here Come the Clouds, appeared in 1975, your eighteenth volume, Night Horse, was published in June this year. I see the same poetic attentiveness and ability to assemble detail that both stalls and surprises the reader. Do you see any changes in the way your write poems, or what you bring to poems, over the past decades?

Elizabeth Caffin wrote of an assured voice but I am unaware of it. I think it is more a question of a philosophy: Keats being lost in the leaves of a tree; being most ourselves when we are unconscious of what the self is; not feeling we are the centre of the universe but one of its parts. It is also a balancing act: the outside world meeting the interior; the sad existing alongside the pleasing, our mixed motives and our inability to ever know more than a fraction. In compensation we have the lovely leap of the imagination. I think poetry in many ways is a dare.

Have any poets or books affected or boosted your poetic directions?

Wallace Stevens was a huge discovery. I used to spend a year reading a major poet. Stevens, Roethke, Berryman, Plath, Sexton, Bishop, Lowell, Synder, The Beats, Black Mountain. Now I am less of a swot and read wherever I please. And when I am tired and jaded I re-read Hercule Poirot.

‘More moon tonight. 14 per cent bigger

and closer to the earth. The whole sky

seems to leap to greet a visitor.’

from ‘Perigee moon’ in Night Horse

In 1975, very few women poets were getting published in New Zealand. Did you feel you were writing within a community of poets? Men or women? Was it difficult to get your first book out?

Part community, part social movement: Greer, Friedan, Steinem, Kedgley, Mead. The United Women’s Convention. We were all swallowing American poets at that time, looking for a freer way forward. My first book I owe to Sam Hunt who was visiting and found a folder of poems he gave to Alister Taylor. After Alister came McIndoe and then AUP.

‘Fast the pulse of the music, every beat

clear as a little stream running over stones’

from ‘At the ballet’ in Night Horse

Your new collection is a delight to read and offers so many poetic treats. I was thinking as I read that your poems are like little jackets that can be worn inside out and outside in. In stillness there is movement and in movement there is stillness; in musicality there is plainness and in plainness there is musicality. In the strange there is the ordinary and in the ordinary there is the strange. What do you like your poems to do?

I want them to do everything. Everything at once. I want them to feel and think (and feel the thinking in them as you read). I want them to be quick, in the old sense of the word: the opposite of dead. I want them to not know something and try to find it out – I would never write a poem with prior knowledge – I think ignorance can be bliss or at least start the motor. And as I write more I find out more and more about musicality. Isn’t one of the loveliest moments in music when harmony breaks through discord as though it is earned and you know that discord, instead of being a thicket or a dark wood, is part of it?

‘Down their sleeves (his jacket, her blouse)

run currents the early evening stars detect

and whose meaning is held in great museums’

from ‘Holding hands’ in Night Horse

I love that idea! What attracts you in the poetry of others?

Boldness, form (the pressure of it), language as clear as it can be, given the difficulty or otherwise of the content, not being self-centred, engaging the reader. Visceral was the quality Allen Curnow looked for when I had the temerity to leave a poem in his letterbox. ‘I poked it with a stick and it was alive.’ James Brown does it in ‘Flying Fuck’ (‘The Spinoff, June 9, 2017); Stephen Romer in some lines about cleaning a barn (‘Carcanet Eletter: Set Thy Love in Order)

‘Perhaps in our cool northern air

you rose some echelons

being lighter, the barn empty’

while Carol Ann Duffy excoriates Theresa May with lines that reach back to the roots of poetry:

‘The furious young

ran towards her through fields of wheat.’

‘Morals that are so pure they blaze

the sunlight back into the air’

from ‘A landscape of shining of leaves’ in Night Horse

Janet Frame worked hard to get the rhythm right in her poems and she wasn’t always satisfied (ah, the rogue self-doubt! I adore her musical effects). I find you are able to slow down the pace of your poems so that I linger as reader upon an image, a word, an anecdote, a side-thought to see what surfaces. Does this reflect your process as a writer?

I think, since I write in longhand, it may echo the pauses during composition.

Do you, like Janet and countless other poets, have poetry anxieties?

Just the big anxiety, the generalised one. To be better, to get closer, to go deeper, knowing that a rigorous equation awaits. I particularly felt this in ballet: any advance, even within the safety of a spotlight, opened a further and equivalent unknown. My other anxiety is that, having embarked on a poem at speed and decided on a stanza form, the stanzas won’t add up when I have finished.

‘Eggs in foil were hidden everywhere

until the taste of sweetness palled.

She sits in an armchair with her bear’

from ‘Ruby and fruit’ in Night Horse

Your poetry does not slip into a self-confession or grant a window on your most private life, yet it acts as an autobiographical record of your relations with the world, people, animals and objects. How do you see the relationship between autobiography and your poems?

Some of the recent autobiographical poems remind me a little of Elgar’s ‘Enigma Variations’. Ruminating portraits of friends or events illustrating a friend. The ‘Enigma Variations’ are tender but well-defined, different in tone. Autobiography, to me, has many hazards. We all excuse ourselves and even the most honest and analytic among us favour some perspectives over others. I feel confident that something of ourselves always gets in and reveals more than we can imagine. ‘Am I in this poem?’ has never worried me. I know I am.

Are there taboo areas?

No, never. It’s just a case of what you can handle.

‘It was all those unseen moments we do not see

the best of a friend, the best of a mother

competent and gracious in her solitude’

from ‘My mother’s house’ in Night Horse

‘Later you’ll scrub individual stains

from the white field: the rim of someone’s glass

down which a red droplet ran, a smear

of eggy quiche, a buttered crumb.’

from ‘The tablecloth’ in Night Horse

I especially love the ongoing friendship and granddaughter poems, but I particularly love the first poem, ‘My mother’s house.’ Kate Camp and I heard you read this at the National Library’s Circle of Laureates and were so moved and uplifted that we asked for copies! Unseen, you are observing your mother move through the house from the street (you gave us this introduction) and see her in shifting lights. The moment is extraordinary; are we are at our truest self when we are not observed? There is the characteristic Smither movement through the poem, slow and attentive, to the point of tilt or surprise. The final lines reverberate and alter the pitch of looking: ‘but she who made it/who would soon walk into the last room/of her life and go to sleep in it.’ Do you have a poem or two in the collection that particularly resonate with you?

I’m fond of ‘The tablecloth’ after I observed my friend, Clay, scrubbing at a corner of a white damask tablecloth in the laundry after a dinner party. It reminded me of the old-fashioned way of washing linen in a river. It’s both a doll-sized tablecloth and something almost as large as the tablecloth for a royal banquet around which staff walk, measuring the placement of cutlery and the distance between each chair. ‘Ukulele for a dying child’ tumbles all over itself in an incoherent manner because the subject is so serious and no poet can do it justice. The grandmother poems will probably be ongoing because it is such an intense experience: something between a hovering angel and a lioness. Going back to your remark about ‘My mother’s house’ I agree with the truth that is available in our unobserved moments. Perhaps there is a balance between our social and our private moments which might comprise something Keats called ‘soul-making’.

‘Next morning she was called again

to undo the work of her marvellous wrists.

“Miss Bowerman, can you let out the water?”‘

from ‘Miss Bowerman and the hot water bottles’ in Night Horse

There is no formula for an ending but I often get an intake of breath, a tiny heart skip when I read your poems. What do you like endings to do?

The endings I like best have some extravagance in them, like the ending of ‘Cat Night’ where the road which still retains the day’s warmth turns into carriages and cocottes on the Champs-Elysées.

‘Let the street lights mark

the great promenade down which love will come

like black carriages on the Champs-Elysées.’

There’s a big difference between the size of a cat and a carriage but the emotion is the same.

Which New Zealand poets have you read in the past year or so that have struck or stuck?

Diana Bridge, Claire Orchard, John Dennison, yourself in New York, Michael Harlow, Geoff Cochrane and all the laureates.

Or from elsewhere?

Lots of Australians. I’ve just read Rosemary Dobson’s Collected Poems.

Do you read widely in other genres?

Yes, I particularly like hybrid forms – travelogues that turn into miniature poetry collections, diaries, memoirs that admit to no rules as if they understand the psychology of the reader who is liable to become bored, and also the limits of being an author. My main love remains the novel, followed closely by the short story and the detective story.

I was once asked to pick a single New Zealand poem I love to talk about on Summer Noelle. What poem would you pick?

Since Allen Curnow: Simply by Sailing in a New Direction, a biography by Terry Sturm, edited by Linda Cassells and Allen Curnow: Collected Poems, edited by Elizabeth Caffin and Terry Sturm are being published by AUP later this year, and since our pohutukawa are threatened by myrtle rust, I would pick ‘Spectacular Blossom’.

‘ – Can anyone choose

And call it beauty? – The victims

Are always beautiful.’

Auckland University Press Night Horse page and author page

Booksellers review by Emma Shi

Radio NZ National review by Harry Ricketts with Kathryn Ryan

With Donna in Berlin, New Year 2013/14.

You have to start somewhere

in these morose times,

a clearing in a forest say,

filled with golden shafts of sunlight

and skirmishes. A little later

your itinerary will take you past

weathered churches on plains that stretch

as far as the eye can see.

from ‘The lifeguard’ in The Lifeguard (2013) and Selected Poems

To celebrate the arrival of Selected Poems (Auckland University Press, 2017), Ian Wedde agreed to talk about poetry with me.

Born in Blenheim (a twin of Dave) in October 1946, Ian has lived in Bangladesh, England, Jordan, France, Germany, now lives in Auckland with his wife Donna Malane, a screen-writer and novelist, they have five children and five grandchildren, has published seven novels and sixteen collections of poetry as well as books of essays and assorted art books and catalogues. Most recent book is Selected Poems (AUP, 2017) with marvellous art work by John Reynolds. New Zealand poet laureate 2011-12, Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement (poetry) 2014.

Cover and internal art work: John Reynolds

The Interview

PG: Did poetry feature in your childhood? What activities delighted you as a young boy?

IW: There wasn’t a lot of poetry in my childhood, though my father chanting John Masefield’s ‘Cargoes’ as he rowed across Waikawa Bay in the Marlborough Sounds was memorable – the rhythm was right but the words were deeply weird to me, which was what I liked.

Quinquireme of Nineveh from distant Ophir,

Rowing home to haven in sunny Palestine,

With a cargo of ivory,

And apes and peacocks,

Sandalwood, cedarwood, and sweet white wine.

PG: What were some key influences when you first started writing?

IW: A link between the deeply lost-in-it world of reading stories and the hypnotic secret ecstasy of writing things, or trying to. Also the fascination of not understanding either what I was reading sometimes (I happened on Browning’s ‘Sordello’ by accident) or why writing was so mesmerising. Also Kipling, because of the poems associated with the Jungle Books, which I was addicted to.

PG: Or at university?