The night sky is full of

stars but

we are more clever than

most – we know

they are just

burned bones.

from ‘Spent’

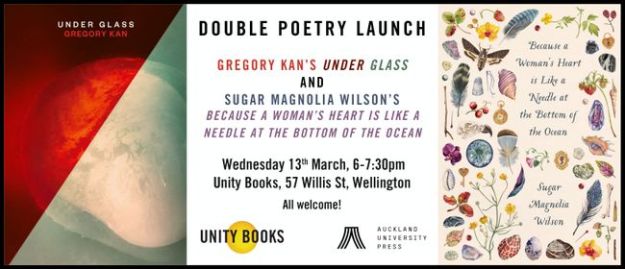

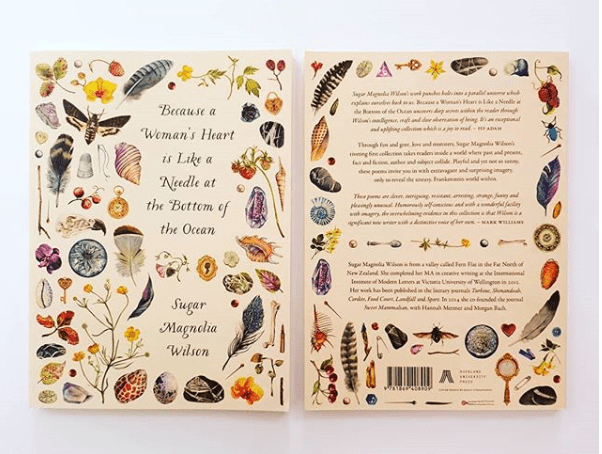

Sugar Magnolia Wilson is from Fern Flat, a valley in the far North. In 2012 she completed her MA in creative writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters at Victoria University of Wellington. Her work has appeared in a number of journals, both in New Zealand and overseas, and she co-founded the journal, Sweet Mammalian, with Morgan Bach and Hannah Mettner. Auckland University Press is launching Magnolia’s debut collection, Because a Woman’s Heart is Like a Needle at the Bottom of the Ocean on March 13th. The new collection is a reading treasure trove as it shifts form and musical key; there are letters, confessions, flights of fancy, time shifts, bright images, surprising arrivals and compelling gaps. Lines stand out, other lines lure you in to hunt for the missing pieces. There is grief, resolve, reflection and terrific movement.

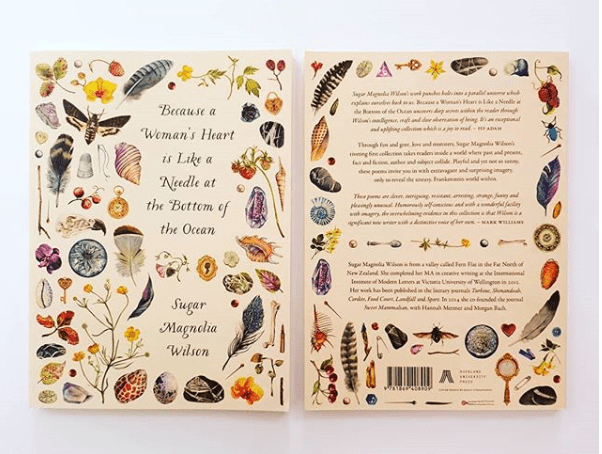

Paula: Tell me about the cover of your book. I just love it. I love the way it is rich in miniature things, a little like your poems are.

Magnolia: Isn’t it totally amazing? When I first received the email from Keely O’Shannessy with several cover design options, I was so blown away by it that I almost couldn’t see it. It was weird, like I was looking at running water in a stream or something and I felt like I might faint. I guess I’d never expected her to ‘get’ my work so completely or so quickly, I was prepared to have to go back and forth to fight for a cover I loved, but that never happened. My friend Kerry Donovan-Brown said it’s like someone took a blood sample from me, put it in a petri dish and looked at it under a microscope, and that the cover is what close up Magnolia Wilson blood looks like! Haha. I wish! Best compliment ever. It’s what my dream blood looks like. I wish my blood was jewellery.

And yes, rich in miniature things. One external review of my book mentioned that I seem to be obsessed with accumulation in my work, and it’s true. Lots of little collections of pins and clips, of food in bowls, jewellery, flowers. I grew up as an only child and I lived a rather sylvan kind of life. I loved to collect bits a pieces and when I was nine Mum, Dad and I travelled around the world (yes, lucky me), and I came home with a giant collection of buttons from different countries. I think it’s an innate desire to hang on to what is beautiful in life, to have proof that beautiful things happened, and is probably tied into grief somehow.

Paula: I first heard you read poems from this book at the National Library Poetry Day celebration and your ‘Dear Sister’ poems – they open the book – blew my socks off. The letter-writing voice drew me in, the sparkling detail, the mood and the mysteriousness. Where did this haunting sequence spring from?

Magnolia: I can kind of trace where they have come from, but like most creative stuff, the true meaning flutters off just before I can pin it down. So, ‘Pen Pal’ was written in 2012, and that’s a letter sequence, and I think that’s where I got the love for the freedom and mystery that epistolary poems allow, and in that same year I wrote a poem called Anne Boleyn, which is also in the book. I started writing the ‘Dear Sister’ sequence with the idea that is was Anne (pre-Henry) writing to her sister, Mary. But, I wasn’t trying to be factually correct I just sort of followed what the letter writer had to say. Slowly it morphed away from being Anne and simply became a woman from another time, struggling with a sense that she was immensely powerful but with no place to express that power. Hence the onset of a kind of ‘madness’ or, more accurately … going full Sybil / turning into a ‘witch’.

Paula: It is such a magnificent way of building a voice in a poem – fierce mixes with doubt, vulnerability, tenderness. This was poetry that I felt. Can you tell me a couple of poetry books that you have felt?

Magnolia: One of the first books of poetry ever gifted to me was Mary Oliver’s collection, American Primitive. My dad set off and travelled around the States after my mother passed away, and he must’ve come across it in his travels and sent it to me with the inscription, Magsie darling, I know you will love this. And I did! It makes me grieve for the majesty of the natural world. I love the way she honours the idea that beauty and love are inseparable from pain and the brutality of nature.

I also love that she is a Christian woman. Usually I would run a mile from a ‘Christian’ poet (probably because I am a bit basic in my thinking and have stereotyped Christians, as though there aren’t a billion different variations on what a Christian can be), but she was Christian in some kind of arcane, pagan way that I love – or that’s what I like to imagine, at least. Also, Mary Reufle’s poetry always makes me feel a lot of hard-to-put-words-to/liminal-space feelings. Her work is a kind of déjà vu. Also, Atsuro Riley’s collection, Romey’s Order, is completely beautiful and was a huge influence for my Pen Pal sequence – the tender, ever so delicate construction-work a child does to build their world.

Paula: Poetry may or may not be something you feel as either reader or writer; it might be a matter of music and mystery, story or ideas. Yet so often a poem knots a complex (scarcely visible) string of effects. Take your poem ‘Home Alone 2 (with you)’, for example. At the core of this poem are multiple loves (a movie, a lover, a mother) and a punch-gut moment. And the after effects last and the questions surface. This is the joy of poetry. You move in and out of self-exposure in the collection. Do you have limits? Is it a form of discovery?

Christmas time and we’ve been out all night.

You’ve been speaking mix of Korean and English,

the way you do when you’re drunk – and

because English is your second language

people can’t be sure if you’re

talking over their heads or if

you’re freestyling your own

kind of poetry.

from ‘Home Alone 2 (with you)’

Magnolia: Interesting. Yes, I definitely have limits. And not purposeful ones for creative constraint etc. They’re the limits of being the specific person that is me with my specific voice and set of issues, trying to write poetry. It’s 100 percent a form of discovery for me, a way of making sense of my world and of growing. I think going back to my interest in accumulation, of objects and imagery, I think maybe it’s a kind of armour.

The lake has a long memory a long

memory, a large imagination.

When my mother left the spring

on our land didn’t change. The water didn’t

stop didn’t stop bubbling up from below.

It didn’t cover itself in a shawl of blackbirds

to indicate grief.

Each litre of water that came up

was different from the next and the next

and each time and each time after that

when I took a drink a drink I became

a deep blue lantern teeming with invisible life.

from ‘The lake has a long memory’

In my poetry I definitely move between self-exposure/vulnerability and then away from it, and I tend to build my poems up and up with imagery like a larva building itself a protective pupa, in order to do its work within, safely. Lol. I think in my poems I build a space where I can work things through, maybe without confronting them directly. And I find that my poems keep on revealing things to me. ‘Muddy Heart’ is an old poem, but only two weeks ago I finally ‘got’ what it was saying. I read it out in an interview and suddenly I was like whoa! That’s what it means! It was so clear and I’d never seen it.

Maybe it’s totally obvious to the reader, I don’t know, but to me I only just got that it was about feeling abandoned by my father after my mum died. I think all creative work is like this, a process of many lives and many mini-deaths, which allow for new life and new understanding in turn.

Muddy heart

You’ll lie down one day on the field behind

your house and your heart will turn

to mud.

Dandelions will push up through the earth, your

blood mingling to a rich beet-coloured soil,

your bones some kind of ash like your father uses

around the strawberry plants.

Clover and pennyroyal will take seed on you.

You’ll call out in the fading light for your father,

who is, after all, just over the fence in the house – but you’ll

sound like the long grass, the frogs, the dogs herding cattle.

When eventually he comes looking for you,

how ever many years later

there will only be the green flush of land down toward

the road, the river and a patch of grass

where he will tend to st from now on.

Paula: It is such a layered sensual poem; I can feel the earth and smell a sharp kick of dandelions just as the image of the father in the fading light who ‘eventually comes looking for you’ is also a sharp heart-kick. And the potent last lines. I adore this poem. The main story might be missing but the feeling is acutely present.

What do you find hard when you write poetry? What gives you pleasure? Does doubt aid or hinder?

Magnolia: I think doubt is something I’m always struggling with in terms of writing. Before I did the IIML masters course, I never really thought much about writing, it was just something that happened to/for me from the age of nine! The IIML course was mostly a blessing and partially a curse. There’s a lot of shit poetry floating round in the world. Honing your editorial eye/ear is key if you want an audience for your work and want to grow as a writer, but, thinking critically about my work pushed me into a place where I felt like nothing was really good enough. I’m only now, seven years on, getting free from that thinking, I am no longer giving fucks.

I am a lyrical, image-laden, nostalgic, confessional poet and that’s totally fine. What I find hard when I write: getting started! I have so, so many failed starts at poems. For every one poem there are maybe 10 or 20 failures. What gives me pleasure: when the creative duende / spirit shows up, and writing just happens in a way that seems outside of my control. It doesn’t happen often but when it does it makes all of the failed attempts worth it.

Paula: Ah yes, I don’t think doubt ever leaves. But that mysterious hard-to-describe poem flow can be such a joy. Have you read any poetry books in the past few years that have given delight? Challenged you? Taken you outside your comfort zone. Given your pure reading uplift?

Magnolia: I’m more likely to love individual poems rather than have entire favourite collections. The poems that’ve struck me in some way or other recently (but aren’t necessarily ‘new’ works) have been: Kiki Petrosino – Witch Wife. Alice Te Punga Somerville – time to write (for Larry), Hannah Mettner, her whole book Fully Clothed and So Forgetful, Emma Barnes – all her poems but especially Ohio. Lynn Jenner – many poems, Rebecca Hawkes – the cave draws u in like a breath, Michael Steven – a sequence of poems he wrote about his son, August. Nina Powles – in the end we are humanlike. Jenny Bornholdt – Flight. Anna Jackson – her whole incredible chapbook, Dear Tombs, Dear Horizon. Faith Wilson – Lynette #1. Cynthia Arrieu-King – her whole book People are Tiny in Paintings of China. Alice Oswald – the whole collection Dart. Morgan Bach – her two new poems in Sport. SO MANY MORE.

Paula: Ok – books for me to track down there. I haven’t read that poem by Nina for a start. Where was it published? I love reading books outside my comfort zone, that are nothing like I will ever write in terms of style, form and content, but I also love those books that refresh my own writing preoccupations. What are key things when you write a poem? Could you narrow it down to three words?

Magnolia: The Nina one was published in The Shanghai Literary Review online.

Three words: really quite random! I don’t know how I write poems. It seems like a bizarre miracle every time it happens, and then I’m convinced I’ll never be able to write another one again.

Paula: I know that feeling – and the way you can pick up an old poem and it reveals new and surprising things to you (as you did with ‘Muddy Heart’). That feels like another miracle. Was there a poem in the collection that just arrived with ease and flow (almost in one sitting) and another that was much harder to form?

Magnolia: ‘The sleep of trees’ was a poem that was just ready and waiting to be written. There had been fragmented, short incarnations of it the year leading up to writing it, but they never worked, and then they all magnetically found their way into that poem, and it was written in about fifteen minutes. And then edited a bit over time.

this is the sleep of mothers – of

five thousand lit candles burning hot in the

dark hall of the body, eyes open

and flaming over the bars of a cot

the sleep of babies – restless turning

a sweet and angry clock

bending in space as it draws earthward, pushing

out and protesting against

the constraints

the boredoms

the repetitions.

from ‘The sleep of trees’

‘Glamour’ also kind of wrote itself. Harder to write – Newton gully mixtape – trying to capture the feeling of growing up in the 80s and visiting fashionable Aucklanders, the party scene my parents were involved in, but the emptiness of the scene at the same time. Don’t think I nailed it – because of course, it was way more nuanced than that. Lots of love and happiness too.

Paula: Your collection offers poetic pleasure because it has music, space and heart and that makes it both open and fertile. I was flying home from Wellington musing on your book and was drawn to the two-part ‘Conversation with my boyfriend’ where you ‘translate’ your experience together from English into Korean, and from Korean into English, not as language translations but as experience translations. I was thinking then how every poem is a form of translation – so capturing the 80s scene is like a flickery translation. I guess if you think of poetry as translation it becomes something new and intriguing with fragile lines to the original experience-thought-feeling.

You are always full of rice because you eat rice and you love rice and

your skin feels like rice when we hug – our bodies mould together

and we are a bread yin and a rice yang and although traditionally

Korean people don’t eat bread you are more than hungry to have me.

from ‘English into 한글’ in ‘Conversations with my boyfriend’

We should always be filled with rice: cooking it and eating meals

together, and rice is important before we die, too. We hug and your

skin is learning to love rice, or, at least starting to star the healthy

map of rice. Traditionally, Korean people don’t eat bread, but there

are now many patisseries in larger cities, and many children long to

be pastry chefs, and I am not so sure about this.

from ‘한글 into English’ in ‘Conversations with my boyfriend’

I loved the way as I closed the book the two translations merged; yin overlaying yang, yang overlaying yin. Would you ever see a poem as translation or at times as performance/acting out or as walking into discovery (like some poets do) or as an opening of the writing valves into a mysterious process (as you indicated above) that is never the same and simply happens?

Magnolia: Love the fact that they close over one another! Hadn’t even noticed that. I think all of those things are true about poems – they are translation, performance, an act of discovery and totally mysterious. Art is a way to translate human experience and I think life is a constant act of translation, layer upon layer of meaning being filtered through our own specific set of circumstances, beliefs and experiences, that have been filtered through someone else’s before us, and will go through someone else’s after us. That’s why I am not really into black and white dichotomies – left vs right, Labour vs Nats, the right thing to say vs the wrong thing to say, male vs female. Life is way, way too nuanced and strange for such basic framing. Hannah Mettner passed on the most excellent quote about poetry to me, by the poet Robin Robertson and it sums up all my moods: I’ve always thought that writing poetry has very little to do with the intellect. It’s not something one can explain and chat about very easily: certainly not about the making of it. It’s very resistant to explanation. It comes from a place that is occult, in the sense of being hidden. It attends to some of our deepest anxieties and hopes in the same way that dreams do.

Auckland University Press page

Magnolia reads ‘Betty as a Boy’