Stepping off from Sue Wootton’s suggestion and Holly Painter’s example – feel free to send photos of what you read or recite when washing hands!

Stepping off from Sue Wootton’s suggestion and Holly Painter’s example – feel free to send photos of what you read or recite when washing hands!

Reading Courtney with Estelle’s portrait of Frida

National treasure Kim Hill opened today’s Saturday morning programme by saying it’s important to be cheerful for the sake of our kids, but it’s okay to feel sad … for just a moment.

I agree. Yesterday I felt sad and overwhelmed and doubtful about the point of keeping two blogs going. I felt gut punched by the demise of so many of our magazines, The Listener in particular (I am a subscriber). Each magazine will be mourned by different groups of people. I mourn the loss of space to celebrate the arts, our vibrant book culture, movies, music, theatre, dance, ideas, along with sport, politics, food, and our lives here in Aotearoa, both ordinary and extraordinary.

I wake at ungodly hours and write poems.

I plant seeds and bake bread and have all kinds of strategies for gladness. Breast cancer gifted me that. But yesterday I felt sad and some of that sadness clings today. I am sitting here wondering whether to switch my computer off until the locks are opened. The internet is a blessing, I find so much to connect with, but it is also a bombardment with invitations to visit this virtual gallery, that mountain, this coastline, that e book, to read this poetry, watch this comic routine, animal antics, Covid facts, quiz, video cuteness.

What to do?

How to be?

I am a hideaway person. I’d rather stay at home. I always feel awkward after public outings. I feel awkward after exposing myself on my blogs. I love performing but I really love being behind the scenes, building an open home for poetry, and in these new challenging times, anything to do with books, and writing and reading. But yesterday in my sadness I felt responsible for adding to the bombardment, for asking authors to contribute this and that to both my blogs.

What to do?

How to be?

But then I think of the child who has sent me a poem from Southland, a comic strip from Wellington, a photo montage, a video, poems from Auckland, Christchurch, little towns. The joy on faces in photos.

That one child, that daisy-chain of children, will keep Poetry Box going.

We are all feeling tough feelings, facing humps and spikes and sad moments. But I am so hoping we can fan these joyful moments. If my blogs can do this, even in the smallest humblest way, then I will keep my open houses going. No matter the spikes.

The other day I got my weekly newsletter from VOLUME bookshop in Nelson. They were offering the chance to order some discounted books that would be delivered once we are out of lockdown. I am in a position where I can still buy books so I leapt at the chance.

I decided to take it one step further and revive my phone-a-bookshop idea and get Stella and Thomas to email a pick (based on what I had picked!) which I added to my pile.

You can join up to VOLUME’s excellent weekly letter and order books here. Stella and Thomas do excellent book reviews!

Here are the books I picked followed by VOLUME’s recommendations:

My picks:

Thomas’s review here

read more here

Read more here

Read Thomas’s review here

VOLUME’s picks:

Stella:

read Stella’s review here

Thomas:

read Thomas’s review here

and he added this one which I couldn’t resist:

full details here

Following on from from my invitation to NZ poets and fiction writers to share a book that has given comfort or solace, I have extended the invite to some of our nonfiction writers.

I am so aware that to write and work at the moment is not easy. I am so grateful for these contributions in these extraordinary circumstances.

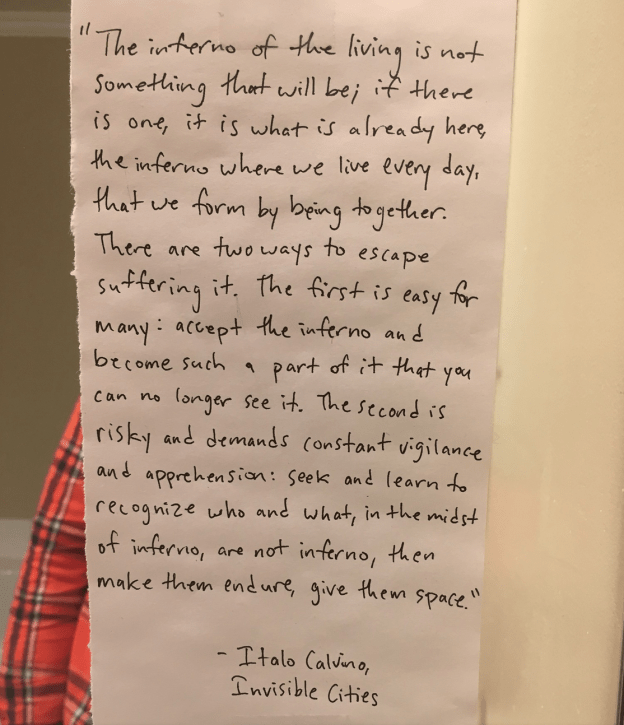

In the middle of the night recently, when I couldn’t sleep, I plugged RNZ National in my ear. I found myself listening to a podcast of Rebecca Priestley in conversation with Lynn Freeman at this year’s Wellington Writers Festival. I have her book in a parcel I am waiting to unwrap. A treat when my anthology ms gets to PRH!

I was utterly transported listening to Rebecca read an extract from Fifteen Million Years in Antarctica (VUP). The writing is elegant, personal, moving. The subject matter is fascinating. I was soothed and inspired and riveted. I can’t wait to open my treat parcel.

Catherine Bishop (Women Mean Business, OUP, shortlisted Ockams 2020)

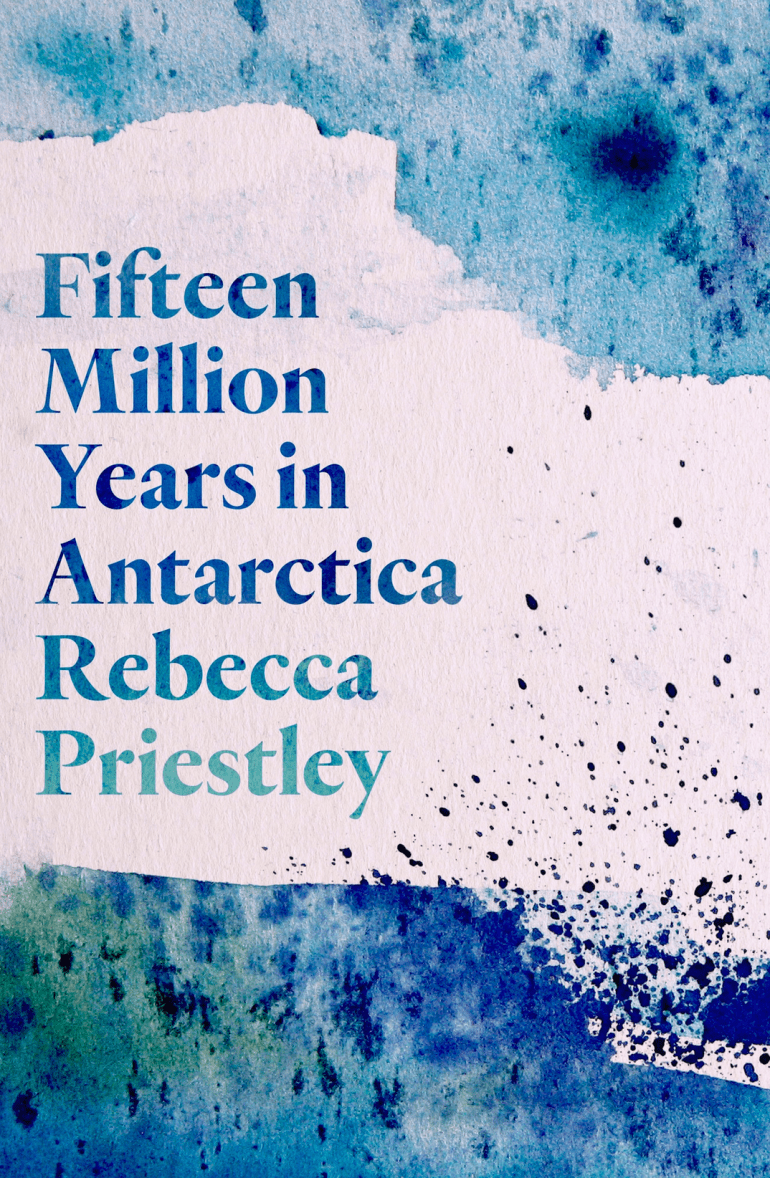

I am in the middle of William Woodruff’s fabulously evocative memoir of his childhood in the 1920s English mill town of Blackburn, Road To Nab End. As a writer I am trying to figure out exactly what it is that he does to make the whole thing come alive – you can just see this little boy running barefoot through the cold damp streets; smell the smoke from the fires and hear the shouts of the neighbourhood fights. His childhood is in many ways desperately impoverished yet there is joy as well as sadness. He draws his characters so well and I just want to keep reading.

Diane Comer (The Braided River: Migration and the Personal Essay, OUP)

The Long Winter by Laura Ingalls Wilder

This is my favorite of the Little House on the Prairie books. It charts the seven month long winter the Ingalls’ family lived through in De Smet, South Dakota. Snow bound, endless blizzards raging, stuck indoors, food and fuel dwindling, the train could not get through with coal or supplies and the town almost starved. A lamp is made with a button, calico and axle grease, they twist sticks of hay to burn in the cookstove, and two men risk their lives to buy grain from a lone farmer out on the prairie. In the midst of deprivation there is hope, endurance and ingenuity.

Jared Davidson (Dead Letters, OUP)

Casey Cep’s Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud and the Last Trial of Harper Lee

I started the lockdown with some grand plans, hoping to get stuck in to some heavy political and social tomes to make sense of these times. But I couldn’t do it. My mind wouldn’t focus. So if you’re like me and struggling to concentrate while reading, I’d recommend Casey Cep’s Furious Hours. It’s a riveting read that blends true crime with social and literary history, following Harper Lee and what she hoped would be her follow-up after To Kill a Mockingbird. Lee never wrote it. Yet in telling the story of why, and by diving into the Alabama serial killer Harper had hoped to write about, Casey Cep does it for her. Furious Hours has won a swag of awards, and for good reason. It’s a page turner that’s thoughtful and accessible.

Joanna Drayton (Hudson & Halls, OUP, Ockham winner 2019)

The book I recommend people read in these challenging times is The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins. I read it when I was a teenager and it was suspenseful and vividly told. An early prototype for the detective novel, it’s full of intrigue. It deals with the desperately unequal rights of sweet guileless Laura Fairlie in her forced marriage to the scoundrel baronet Sir Percival Glyde. This novel offers a complete escape from reality. All your grey cells will be caught-up in solving the mystery.

Martin Edmond (The Expatriates, BWB Books)

I choose The Book of Disquiet – the complete edition, by Fernando Pessoa, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and edited by Jerónimo Pizarro (Serpent’s Tail, 2018). Because you can open it at any page and there find consolation, even wisdom, without sentimentality and without affectation either. Also it’s funny, so long as you are willing and able to laugh in the shadow of the gallows. It’s beautiful too. Here’s a paragraph selected at random:

The coming of autumn was announced in the aimless evenings by a certain softening of colour in the ample sky, by the buffetings of a cold wind that arose in the wake of the first cooler days of the dying summer. The trees had not yet lost their green or their leaves, nor was there yet that vague anguish which accompanies our awareness of any death in the external world simply because it reflects our own future death. It was as if what energy remained had grown weary so a kind of slumber crept over any last attempts at action. Ah, these evenings are full of such painful indifference it is as if the autumn were beginning in us rather than in the world. (#319, p. 294)

Paul Millar No Fretful Sleeper: A Life of Bill Pearson AUP

Unusually I have four books on the go, all of which I’ve read before. Probably inevitably each one seems to offer some perspective on our COVID-19 situation.

I’m teaching Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea from lockdown. This requires some in-depth re-reading as I turn my lectures into on-line teaching modules. Capote’s initial impulse for In Cold Blood was to explore the way one horrific event, the shotgun executions of the Clutter family, might rupture and reshape a previously safe and peaceful community. His masterpiece is remarkable for the extent to which he exceeded those early intentions, taking time to understand (or else imagine) the perspectives of everyone involved, including the murderers. Rhys does something similar in Wide Sargasso Sea by imagining a life for Jane Eyre’s terrifying madwoman, Bertha Mason, the wife Rochester imprisoned in his attic. I wonder to what extent those with the power to shape our post-coronavirus future will accommodate different perspectives and give a voice to the voiceless?

Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep has been on top of my reading pile since before the pandemic. I’m not sure why I decided to re-read it. I don’t enjoy it much—every time I emerge from a chapter I feel like I need to wash off kipple dust. But for a book written fifty years ago, it is chillingly, brilliantly prescient in its depiction of life in a world sickened beyond humanity’s capacity to cope.

As far as non-fiction goes (I don’t mind debating which genre Capote belongs to), I’ve been re-reading Naomi Klein’s No Is Not Enough: Defeating the New Shock Politics. Klein published this in 2017, but much of it is so apposite it’s like she wrote it yesterday. I wish I could quote her entire conclusion, but as I can’t I’ll quote just this:

But crises, as we have seen, do not always cause societies to regress and give up. There is also the second option—that, faced with a grave common threat, we can choose to come together and make an evolutionary leap. We can choose, as the Reverend William Barber puts it, “to be the moral defibrillators of our time and shock the heart of this nation and build a movement of resistance and hope and justice and love.” We can, in other words, surprise the hell out of ourselves—by being united, focused and determined. By refusing to fall for those tired old shock tactics. By refusing to be afraid, no matter how much we are tested. (p. 266)

Gregory O’Brien Always Song in the Water: An Oceanic Sketchbook AUP

Is it possible to be solemn and lively at the same time? To be intellectually dexterous (and rigorous) yet emotionally charged (and driven)? Stephanie De Montalk’s 2014 memoir/book-length-essay How Does It Hurt? is centred on a personal experience of chronic pain. Despite the anxiety and trauma that engendered it, the book is commendably–miraculously, in fact–free of self-pity and maudlinism. How Does It Hurt? is a book that reaches out–generously, intelligently and plausibly–beyond the circumstances of its making to celebrate the life of mind and soul. An earlier book by De Montalk, Unquiet World–The Life of Count Geoffrey Potocki De Montalk, is another unique and unexpectedly uplifting creation. Years back, Michael King said to me that he thought Unquiet World was one of the best books ever written in Aotearoa. I doubt either of these books quite reached the wide audience they deserved. Both of her non-fiction works, and the flotilla of poetry collections that sail alongside them, are edifying and consoling. Whether we, her readers, are confronting Covid-19 or cycles of human life and death more generally, these books are a spirited engagement with what it means to be interestingly, if at times paradoxically, human. There’s strength in that.

Elspeth Sandys A Communist in the Family: Searching for Rewi Alley, OUP 2019

Every reader loves a quest story, where the hero or heroine sets out on a journey to fulfill a challenge, reach a mythical destination, or find her particular holy grail. Jackie Kay’s Red Dust Road is a quest story disguised as a memoir. Born to a white mother and an African father, Jackie was adopted into a loving, highly energized Glaswegian communist family. Red Dust Road tells the story of her search for her birth parents. As she crosses continents, bridging racial and religious divides, she faces challenges that range from the hilarious to the devastating.

It’s an astonishing story, reminding us that even in the pre-pandemic world, connection is what matters. Only by acknowledging our shared flawed humanity can we hope to survive.

Peter Simpson (Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction, AUP)

In such strange times I take solace from any book in any genre which is absorbing, well-written and on a subject that deeply interests me. A non-fiction title which easily fulfils all these categories is The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles by Martin Gayford (Penguin, 2006). The title explains the subject of the book and its scope. It focusses on a celebrated episode from art history ending with van Gogh’s notorious act of self-mutilation, which is usually described from the perspective of one artist or the other but not from both. By focussing on such a brief period in the lives of both artists Gayford is able to write in great detail drawing on multiple points of view. I have read several of Gayford’s books. He writes the kind of art history I aspire to write myself, in that it is scholarly and visually well-informed but written in an accessible style for general readers not just specialists. He also makes great use of letters, paintings and other contemporary documents as I like to do myself.

Diana Wichtel (Driving to Treblinka, Awa Press)

You wouldn’t read about it, my mum used to say, constantly gobsmacked at how real life outdoes art when it comes to marvels, miracles and messes. I love fiction but I’ve taken particular solace from the singularity of lives not made up but valiantly lived on this increasingly improbable planet. Before I began piecing together the fragments of my own family, the Bloomsbury Group were my fantasy surrogate tribe. To the Lighthouse was good. Snapshots of Bloomsbury: The Private Lives of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell was thrilling.

In the reading life, a book of endless consolation can be a comic about the Holocaust. Art Spiegelman’s Maus is autobiographical. Nothing less would allow him to get away with his risky, agitated drawings of Jews as mice, Nazis as cats, Poles as pigs. Almost immediately they are just characters making choices or having all choice taken away from them. Spiegelman’s parents were survivors. The brother he never knew was poisoned by an aunt when capture by the Nazis seemed inevitable. His material has included the suicide of his mother and his own mental breakdown. He made comics about it all that are audacious and, especially in the relationship between Artie and his dad Vladek in Maus, often funny. “From this you make a living?” his father once asked Spiegelman. Maus is a comic book about the effort it takes, after losing everything, to hang onto anything. It’s worth hanging onto.

The Complete Maus, by Art Spiegelman, Penguin, 1986.

Hello Strange by Pamela Morrow (Penguin Random House)

This month this fabulous young adult novel hits the virtual shelves, and you can access a copy through numerous channels outlined here.

As soon as bookshops open again, you can of course also purchase physical copies, and I urge you to do so, not just because this is a high-paced, funny, stimulating, thought-provoking and entertaining read, with the added bonus of a lively layout, but also because both the author and the shops need all your support given the challenging timing of this launch. The Women’s Bookshop on Ponsonby Road was all set to host the event, so a big shout out to Carole and her team.

When I was about six, the height of scientific enterprise that encapsulated the excitement of the future was not the moon landing; after all, we queued up for ages to see a small lump of dusty moon rock that was, quite frankly, a huge disappointment. No, for me it was the Super Ball, the brightly coloured bouncy sphere of synthetic rubber called (Wikipedia informs me) Zectron. To a little girl, this seemed the height of scientific innovation: if you could make this tiny object bounce from floor to ceiling, endangering any ornaments in its path, then the future was going to be a wonderfully exciting place. Sad, I know, but toys have come a long way since then.

So, why am I wittering on about Super Balls? For two reasons. First, when Pamela sent her first draft in, it was evident there was something really special in there, but it needed work. So, I dashed her hopes to the ground with demands for changes and, like a Super Ball, she bounced back up again producing something far higher than my expectations. We went through that process several times, and Pamela just kept bouncing higher, a whizzing, psychedelic ball of energy and creativity, with added glitter. This is a sign of a true writer: someone with great ideas and a way with words and, most importantly, the perseverance and bounce of a Super Ball.

Secondly, although my imagination was tickled by a lump of synthetic rubber, Pamela’s imagination leaps as high and as far and as unexpectedly as those balls. Her vision of the future is fun and zany, but actually credible and well researched. From the talking toilet cubicles in school to the mood suit, her future is varied and intriguing, and a place I wanted to spend time in through the pages of her book.

Hello Strange has lots of heart (including a mechanical one and a humanoid one), vibrant characters, a compelling plot and is a moving exploration of grief.

So, for all readers from about 12 upwards, do escape this world into the future, as created by this exciting, irrepressible, Super Ball of a new writer, Pamela Morrow.

Here’s a sneak peek at the beginning

Harriet Allan, Fiction Publisher

Frances Edmond reads ‘Late Song’ by her mother Lauris Edmond

Night Burns with a White Fire: The Essential Lauris Edmond (Steel Roberts, 2017)

Lauris Edmond, 1924–2000, grew up in Napier, and attended Wellington Teachers’ College, Victoria University College (1942–44) and Canterbury College (1944). She completed an MA in English literature with First Class Honours at Victoria University of Wellington. She wrote poetry, novels, short stories, stage plays, autobiography and edited several books, including a selection of A. R. D. Fairburn’s ltters. She published seventeen volumes of poetry, including several anthologies, and a CD, The Poems of Lauris Edmond, which was released in 2000. Her debut collection, In Middle Air (Pegasus Press, 1975), wri tten in her early fifies, won the PEN NZ Best First Book of the Year (1975) and Selected Poems (Oxford University Press, 1984) won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize in 1985. She received numerous awards, including the Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship (1981), an OBE for Services to Poetry and Literature (1986), and an Honorary DLi from Massey University (1988). Edmond was a founder of New Zealand Books. The Lauris Edmond Memorial Award was established in her name. Her daughter, Frances Edmond, and poet Sue Fitchett published Night Burns with a White Fire: The Essential Lauris Edmond (Steele Roberts), a selection of her poems, in 2017.

Today Emma Neale was announced as the 2020 winner of the Lauris Edmond Memorial Award for Poetry.

Frances Edmond is a writer and reviewer who works across disciplines in film, theatre and literature and is Literary Executor for her mother, poet, Lauris Edmond. Her most recent completed projects include: Night Burns with a White Fire: THE ESSENTIAL LAURIS EDMOND (with co-editor Sue Fitchett and published by Steele Roberts Aotearoa) and she is now working on a companion piece tentatively titled, Burning Substance: a Lauris Edmond Companion, which explores the origins, sources and inspiration of her mother’s writing through a daughter’s eyes. Frances was the 2018 recipient of the Shanghai Writing Residency and spent two months in Shanghai working on a new draft of her screenplay about New Zealand Missionary Nurse, Kathleen Hall, and her experiences in China. With Ken Rea who teaches at the Guildhall in London, and who was the founder of the Living Theatre Troupe (1970-76), Frances is working on a history of the Troupe based on completed oral histories that were funded with a Ministry of Culture and Heritage Oral History Award. She has also written and directed her own short film, The Apple Tree.

So delighted to see this news. Congratulations Emma Neale!

Emma Neale is the author of six novels and six collections of poetry. Her most recent novel, Billy Bird (2016) was short-listed for the Acorn Prize at the Ockham NZ Book Awards and long-listed for the Dublin International Literary Award. Her new book of poems is To the Occupant which was published in 2019 by Otago University Press. Emma is currently editor of the iconic Aotearoa literary journal, Landfall.

On receiving the award, Emma says: “I’m incredulous, happy and stunned in my tracks, as if someone has thrown a surprise party – the way friends did when I was nine, and they waited to jump out at me until I was standing near the host’s swimming pool. All the other nine-year-olds were hoping I’d fall into the water with shock. I didn’t. So here I am, dry, a bit disoriented and also delighted again, and remembering that Lauris Edmond was the first poet I ever heard give a public reading. When I was 16, I caught the bus alone to a Book Council lunchtime lecture during school holidays in Wellington, and went to hear her talk about her writing career. I have a feeling I’d sneaked out of the house to do it – as if my interest in poetry and my aspirations to write it were somehow going to get me into trouble, and my parents and friends shouldn’t know. I sat and listened on the edge of my seat, as the poems and the talk opened a portal that meant I could glimpse the green and shifting light of hidden things. The portal was still a long way off, but I was convinced that poetry and literature were going to carry me into an understanding of intimacy, identity, time, ethics, deeper metaphysical questions.

I still think of Lauris Edmond as a kind of poet laureate of family relationships; her work was immensely important to me as the work of a local woman poet I could not only read on the page but also hear in person. I am just sorry that I can’t thank her face to face for what her work has meant to me, and I’m enormously grateful to the Friends for reading my own poetry and giving me this generous award. I’ve pinched myself sore. I actually feel like leaping into a pool.”

Established in 2002, the Award is named after New Zealand writer Lauris Edmond who published many volumes of poetry, a novel, a number of plays and an autobiography. Her Selected Poems (1984) won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize.

The 2020 award was announced on 2 April the date of Lauris Edmond’s birthday. A ceremony and birthday celebration was due to take place at National Library of New Zealand in Wellington on 3 April to honour Emma, however due to COVID-19 the event is postponed and will take place in collaboration with Verb Wellington later in the year.

Full release here with two new poems by Emma

from Southerly, Vol. 278 ‘Violence’, 2018

Wen-Juenn Lee writes and works in Melbourne. Her work has appeared in Landfall, Southerly, and other places.

Not Very Quiet accepts poems from women poets in NZ and Australia. Here is a link to the latest issue which features a couple of well known Kiwi poets and emerging poets such as Sophia Wilson.