Mahmoud Darwish

from ‘The Andalusian Epilogue’

Because it’s our last evening on this earth we extract our days

From their leafy camouflage and count the coasts we’ll encounter

And those we’ll leave. There. On this our last evening

There’s nothing left to farewell and no time for fanfares.

This is how everything’s governed. How our dreams are renewed,

Our visitors. Suddenly irony’s beyond us

Because the place is set up to accommodate nothing.

Here, on the last evening

We moisten our eyes with mountains encircled by clouds.

Conquest and reconquest

And an earlier time that relinquishes our door-keys to the present.

Come into our houses, conquerors, and drink our wine

To the music of our mouwachah. Because we are the night’s midnight.

And no courier-dawn gallops to us from the last call to prayer.

Our green tea is hot, drink it, our pistachios are fresh, eat them,

The beds are of green cedar wood, yield to sleep

After this long siege, sleep on the duvet of our dreams.

The sheets are spread, perfumes placed at the doors

And by the many mirrors.

Go in there so we can leave, finally. Soon enough we’ll seek out

The ways our history wraps around yours in distant regions.

And at the end we’ll ask: Was Andalusia there

Or over there? On the earth . . . or in the poem?

(after the French translation by Elias Sanbar of Darwish’s poem in Arabic)

©Ian Wedde The Lifeguard: Poems 2008 – 2013 Auckland University Press, 2013.

The poem I have chosen, ‘Mahmoud Darwish’, is taken from Ian Wedde’s collection The Lifeguard: Poems 2008 – 2013 (Auckland University Press, 2013). This is a book mostly made up of sequences of interlocking poems. One of the sequences is called ‘Three Elegies’, and consists of three poems, titled, respectively: ‘Harry Martens’, ‘Mahmoud Darwish’ and ‘Oum Kalsoum’. These are connected through the life and work of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish (1941 – 2008). The elegy for Harry Martens remembers an exuberant traveller, linguist and poet, one Harry Martens, who translated Darwish, while the elegy for Oum Kalsoum celebrates a famous Egyptian singer and media star — acclaimed generally as the single most prominent Arab woman in twentieth-century history — who died in 1975. In this latter elegy, Wedde recalls hearing her in the early 1970s ‘singing Darwish in Cairo, /reprise after reprise’, a performance he watched at the time on a TV set in Amman, Jordan.

Of the central poem ‘Mahmoud Darwish’, it could be said rarely has a poem seemed more pertinent than this one right now, when, preening himself like an orange budgerigar, President Trump is obsessively chirping anti-Muslim, anti-Arab tweets on Twitter, intent on scapegoating and marginalising Arab citizens as the dangerous Other. Mahmoud Darwish (1941- 2008) was one of the most accomplished modern poets, not just of the Arab world, but internationally. Furthermore, he is one of the emblematic poets of loss of homeland and exile, of ‘destroyed identity’ — and the central literary figure in Palestinian culture.

The Israelis razed Darwish’s home village to the ground in 1948, when he was seven. He grew up in occupied Palestine. Emerging as a significant young writer in the 1960s, he was imprisoned for reciting his poems, harassed, banned, and eventually sent into exile by the Israeli authorities: a permanent refugee.

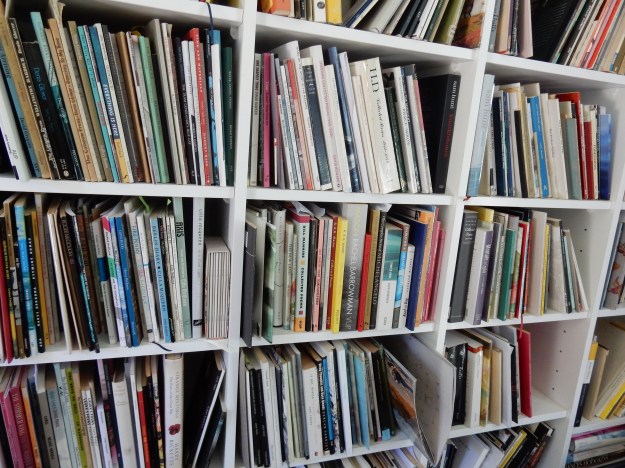

Ian Wedde, working with the Arabic scholar Fawwaz Tuqan, translated a number of Darwish’s poems into English in the early 1970s, and Carcanet Press in the UK published these as a Selected Poems in 1973. A copy of this slim volume in its now-faded yellow dust-jacket resides on my bookshelves.

‘Mahmoud Darwish’, however, is not a poem directly about the poet; instead it is a translation from an original poem by Darwish, filtered through a translation into French by Darwish’s friend and fellow Palestinian writer Elias Sanbar. One affinity between Darwish and Wedde is that they are both philosophical poets, ontological poets, concerned with exploring being-in-the-world through language. Another affinity is that they are both cosmopolitan poets, restlessly alert to contexts and cultural allusions. Many of the poems in The Lifeguard emphasise a kind of stream-of-consciousness effect, or are, in their reverie, even occasionally teasing reminiscent of Walter Benjamin on hashish.

‘Mahmoud Darwish’ picks up on the same phenomenological pressure, but then artfully opens out into a sort of liminal dream space. Its verbal music, at first acquaintance, seems to have an air of yearning, as it evokes what might be a mirage, an oasis, a sequestered courtyard. But gradually, reread, the poem becomes increasingly haunting, subtly plaintive, and the tone you might at first take for lassitude, world-weariness, melancholy, begins to resonate in a more complex way. Beneath the incantatory language and luscious imagery, the air of fatalistic resignation, is a smouldering anger and underlying bitterness.

Wedde has actually only selected the first of eleven poems in Darwish’s original ode sequence, titled by one translator ‘Eleven Stars Over Andalusia’, or as Wedde calls it ‘The Andalusian Epilogue’. All the poems in the original sequence are variants of classic Arabic verse forms, pushing and pulling and prescribed rhyme schemes and standard imagery.

Andalusia in southern Spain is a mythical homeland for the dispossessed Palestinians. It’s a region of medieval artistic accomplishments, where Muslims, Jews and Christians lived together in harmony for centuries until Muslim Spain — al-Andalus — was conquered by Christians from northern Spain in 1492. Darwish wrote this poem on the anniversary of the Fall in 1992, in part in response to Yassir Arafat’s peace negotiations with Israel at that time, which Darwish regarded — rightly, as it turned out — pessimistically. ‘Mahmoud Darwish’, then, is a poem about harsh realpolitik, only cast in sensual cadences; it’s a poem of disillusionment, affirming a lost cause. The tribal bard calls on his people’s collective memory to mark the ongoing occupation of the homeland and the intransigence of the conqueror — that conqueror’s policies of eradication, subjugation, apartheid — in language reminiscent of the Song of Solomon.

David Eggleton

David Eggleton lives in Dunedin, where he is a poet, writer, reviewer and editor. His first collection of poems was co-winner of the PEN New Zealand Best First Book of Poems Award in 1987. He was the Burns Fellow at Otago University in 1990. His most recent collection of poems, The Conch Trumpet, won the 2016 Ockham New Zealand Book Award for Poetry. He is the current Editor of Landfall, published by Otago University Press.