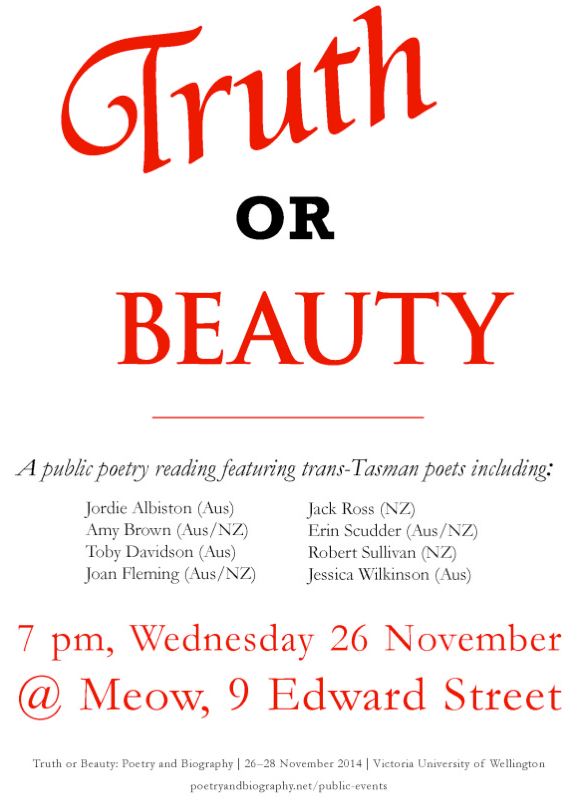

Anna Jackson teaches English Literature at Victoria University and has published five collections of poetry. Thicket was shortlisted for the New Zealand Post Book Awards, and Auckland University Press has just released her new collection, I Clodia, and Other Portraits. To celebrate the arrival of this terrific new collection, Anna agreed to be interviewed by me. With poet and publisher, Helen Rickerby, Anna has organised, Truth or Beauty: Poetry and Biography, a conference currently running at Victoria University (26th to 28th November).

Did your childhood shape you as a poet? What did you like to read? Did you write as a child? What else did you like to do?

Reading and writing and making up long extended stories in my head were almost all I ever did, that and keeping pets, pretty much the same as now. Everything else was an interruption – children are always being interrupted from their purposes.

When you started writing poems as a young adult, were there any poets in particular that you were drawn to (poems/poets as surrogate mentors)?

To begin with the more musical poets, like Yeats, and my own poetry rhymed and was metred, I often wrote in a ballad metre. I wrote a wonderful long verse poem and then later found whole lines from it were lifted straight from Yeats – I’d remembered them but thought I’d made them up. The Romantics too – Keats and Shelley. But I was also reading Beckett, the novels, for the prose rhythms, which I found breathtakingly funny, and Pinter, again, for the rhythm.

Did university life transform your poetry writing? Discoveries, sidetracks, peers?

Murray Edmond was my tutor in twentieth-century literature and when I showed him some of my own poetry he told me I had to stop writing in metre and rhyme. The next year in modern poetry taught by Don Smith we learned about Ezra Pound modernising Yeats and about the rigorous line breaks of William Carlos Williams, and then the next year I took American poetry with Wystan Curnow and Roger Horrocks and that was revelatory, and challenging because the experimental L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets disturbed and disappointed me as much as they excited and inspired me, and I had to try and make sense of my conflicting responses. There was also always the pleasure of listening to Wystan talk – just like reading Beckett, it wasn’t what he said so much as the rhythms of the sentences – and Roger’s extraordinary generosity as a teacher responding to every student’s individual interests.

Does your academic writing ever carry poetic inflections?

No.

Are there any theoretical or critical books on poetry that have sustained your or shifting your approach to writing a poem?

I like this question and I teach a class on poetry and poetics which is founded on the idea that writing poetry and thinking about poetics, and reading poetry theory, ought to go together. But I can’t think of any poetry criticism or theory that has made any direct difference to anything I’ve done. Poetry criticism I have liked includes James Fenton’s The Strength of Poetry, Helen Vendler, especially The Making of a Poet, and James Longenbach, The Virtues of Poetry. Virginia Woolf is wonderful writing about poetry, although she hardly ever does – she chooses to write about Dorothy rather than William Wordsworth for instance. But her essay on Donne is brilliant. I used to find Ezra Pound an essential guide to poetry though reading The ABC of Reading now I can’t imagine how it could have helped; still, as Pound writes on page 86, “There is no reason why the same man should like the same books at eighteen and at forty-eight.”

Indeed! What poets have mattered to you over the past year? Some may have mattered as a reader and others may have affected you as a writer.

Can I go back further? The only poetry I think I’ve ever read that actually gave me the physical reaction that Robert Graves claims is the test of poetry, the hairs standing up, the shiver down the spine, the reaction that Emily Dickinson describes as feeling as if the top of your head has come off, is the sequence JUMP, from C K Stead’s The Black River, published in 2008. This is a sequence he wrote after a stroke in a state of semi-dyslexia. Some of the images – death as a Picasso, with a hole in the head – are terrifically, strangely vivid and funny. Some of the puns would seem banal in another context – the mine of the mind – and the wordplay on old rhymes and quotations is often simple enough in itself. But altogether, the effect is extraordinary. It really does somehow feel like he is mining the mine of the mind. It seems to reveal something about the way we think in language, something about the way language works, and there is an almost frightening spirituality about it. The capitalized word JUMP provides section breaks through the sequence, and by the end, the announcement can be made “faith hope the JUMP/ these three abide/ and the greatest of these/ is the JUMP.” This seems true, because we have experienced the way God, or religion, or some sense of an enormous and frightening significance can work through the gaps in language, through the jumps offered by dyslexia, a stroke, poetry.

More recently, in the last year or so, collections that have been very important to me include Helen Rickerby’s Cinema, a witty, perceptive collection of poems about the role of cinema in our lives; Ashleigh Young’s Magnificent Moon, a peculiar and wonderful blend of the surreal and the personal, the lyrical and the essayistic; and your own (Paula’s) The Baker’s Thumbprint, with its kaleidoscopic cast of characters, its richly rendered West Coast setting, the light of it, the weight of memory, the lift of imagination.

And then perhaps the most amazing publishing event of the last year was the publication of the newly discovered Sappho poem, “The Brothers,” with the TLS offering a spread of different translations of it – including a hilarious one by Anne Carson, wonderfully freewheeling and playful with its contemporary (and not so contemporary) references, while seeming at the same time to go straight to the psychological core of the poem. Even more moving to me though was the translation by Alistair Elliot – I was just so profoundly moved by the technical brilliance of it, as he apparently effortlessly translated the Greek metre into a perfect English equivalent, while – it seems, comparing only the different versions other poets offered – capturing most closely the sense of the original, the significance, in relation to the logic of the poem, of the details.

And that reminds me of one more translation event I found terrifically exciting which was the debate between Tom Bishop and Steve Willet in the journal Ka Mate Ka Ora over the translation of a Tibullus poem. I thought Tom Bishop won in terms of debating points, and loved his translation, but it was the level of debate and the skill of both translators that made it such a brilliant and absorbing conversation to follow.

(a link: http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/kmko/11/ka_mate11_bishop.asp)

What New Zealand poets have you been drawn to over time?

I expect I’m going to leave out some names that afterwards I’ll think of with amazement and regret, but among the poets whose work I return to again and again are Bill Manhire, of course, for the rhythms, the lift of the writing (I always hope to catch it a bit), and Jenny Bornholdt again for how rhythmic her poetry is, the way she plays with the rhythms of ordinary speech. Maybe this emphasis on rhythm is surprising, since I think my own poetry is quite prosaic. Though her rhythms are also quite prosaic – I like prosaic. Jenny Bornholdt and Bill Manhire are the poets I’ll read with the feeling that I can sort of catch poetry from them. A new Ian Wedde collection is always an event, and I loved The Lifeguard which came out last year, but I also return often to his earlier collections. I love the experiments with the sonnet in the Carlos sonnets, the intricacy of them and the ease, and I return again and again to the Commonplace Odes, again, the ease, the scope of them. Ease is the word I think of with Robert Sullivan’s poetry too and again that combination of ease and scope – the ease seems to allow the scope. But then again, the nervy tautness of Anne Kennedy’s poetry is tremendously exciting, and though scope isn’t the word that comes to mind in the same way, I like how her collections are always about so much, how she tells stories. James K Baxter, another story-teller, and a poet like Wedde and Sullivan with that combination of ease and scope – I return again and again to the sonnets, that relaxed sonnet he invented. C K Stead got closest to describing how it works, how it depends on a determined and consistent evenness of emphasis, a turning away from metre that is almost a metre in itself.

Your poems always offer surprise, a fresh and vital view of things and idiosyncratic musicality (an Anna Jackson pitch and key). What are key things for you when you write a poem?

Tautness? And that the poem has enough in it?

Your new collection, I Clodia, reflects a return to sequences that are thematically linked as opposed to discrete poems with more accidental connections. What drew you to this choice?

I far prefer writing sequences, I find building a sequence tremendously satisfying, and at the same time, it is far easier writing from within a sequence that is already underway than it is to generate new poems out of nothing. But not everything will fit into a sequence, so you have the discrete poems as well, and it can be very pleasing just writing a poem out of nothing, it can feel like a small miracle. And a single poem can be written in a very small space of time. It can rescue a day or a week that wouldn’t have had any poetry in it. I always wanted to write the Clodia sequence, but I wanted to so much, I put it off, till I had enough time to make the most of it. The photographer sequence started out just as a single poem about a photographer, which I wasn’t really sure was even a poem at first. But then after that, whenever I started another poem and didn’t know quite what to do with the material, the image or the idea, all it seemed to take was to attribute the experience to the photographer and it seemed to turn into a poem – it gave the material a dramatic element, a fictional element, that made it do just enough more to suffice for a poem. So then I started adding names to the titles of some other poems and found it gave them the same lift, and got interested in the idea of portraiture so wrote more portraits. I don’t think of that half of the book as a sequence so much as a collection of portrait poems – some of which I converted into portraits afterwards. But the Clodia sequence is very much a narrative with a three act structure, a cast of characters, a problem, a low point, a decisive action, and a resolution. I don’t think anything has ever been more fun to write.

And what of Catallus? Why does this subject matter resonate with you so strongly?

There’s a terrific essay by a classicist Maxine Lewis that discusses the reasons why writers and scholars are drawn to make narratives out of the Catullus poems (“Narrativising Catullus: A Never-ending Story,” in the Melbourne Historical Journal Volume 441:2, 2013). There are characters that recur in poem after poem, situations that seem to unfold, changing feelings, a developing relationship, and a complicated chronology that the order of the poems seems to defy. It is impossible to read the poems without trying to construct some sort of narrative – and as you do this, you begin to make the narrative your own, to act as a writer as well as a reader. And then, the poems are so funny, often, so passionate, and often so angry. They are also poems about writing poetry, or about the kinds of relationships that can be built around the exchange of poetry, and exchanges of wit. And love, and all the tumultuous feelings it evokes, has always been the best of themes for poetry.

And what of the point of view of women rather than the dead white men?

I write as Clodia because I love the poetry of Catullus, and I love him no less for being dead. But the point of view of Clodia is everywhere suggested, implied, presented or argued against in the Catullus poems – she is not just a character described by the poetry, but an implied reader teased, provoked, and responded to. The poetry invites an active engagement – I just couldn’t resist.

You gained a grant to undertake substantial research for this poetry project. Did you make serendipitous discoveries that flipped or fine-tuned what and how you wrote?

I made discoveries I really didn’t want to make. I had to give up on the first poem I wrote for the sequence, because it wouldn’t work with the chronology I developed. I had seasons in the wrong places, I had events happening simultaneously that had to happen two years apart. But I was able to work out a chronology that didn’t contradict any of the known dates or facts and allowed for a coherent story to take shape. The most important narrative breakthrough came in Rome, when I was doing nothing but work on the sequence and so could think always in terms of the narrative with an overview of the whole sequence, not just thinking one poem at a time. I had reached an impasse, and decided to go on a long walk along the river. I’d only taken a few steps out the door when I realised the solution that would make the whole story work. I kept walking for two hours, and then came back and wrote what I would have written if I’d turned back after five minutes. But I wouldn’t have had that five minute breakthrough without the weeks of sustained thinking and writing that led up to it.

The second part of the book is like a parade of characters, startling and askew with life, that may have strayed from a Fellini film. They glisten and glow on the page. There seems to be more invention and less autobiography that has marked many of your earlier poems (although not all!). Why this predilection to step into the shoes of others?

I love this description of the photographer section! I think photography has a glamour about it I have borrowed for the poetry. I am not sure how much less autobiographical the poetry really is. Even when I put my own children in to poems, as in “Tea-time with the Timorese”, often I made up the events. In Thicket, my previous collection, I might write as “I” but the “I” is as invented as a character like Saoirshe or Roland in the photographer sequence. And, conversely, I could have written the Saoirshe poem or the Roland poem as “I” – both are stories about my own life, in a way, in the same way the Thicket poems are. Perhaps it is a trick on the reader, perhaps the reader brings more to the poems when given a range of character names to lend the imagination to, perhaps the reader is able to read the poems more as stills from a film?

The constant mantra to be a better writer is to write, write, write and read read read. You also need to live! What activities enrich your writing life?

I completely agree and think the best poetry is, as Leonard Cohen said, the ash from a life burning well. I don’t like poetry about writing poetry, and the song that most embarrasses me is Gillian Welch’s song about not being able to make up a song – I don’t want to know! If you can’t think up a song, don’t sing one. But the truth is, I am unusually lazy and do less than just about anyone I know – almost nothing other than read and write, and have long baths. I have written a few poems about my hens, hen-keeping being my one hobby, if you can call it a hobby, but there are only so many poems you can write about hens and I think I’ve already reached my limit. So, I can’t think of an honest answer. Talking to my friend Phoebe, maybe? I quite often end up writing down bits of things we’ve said. Some of my best poems are probably actually just things Phoebe thought of.

Finally if you were to be trapped for hours (in a waiting room, on a mountain, inside on a rainy day) what poetry book would you read?

I’d want to read the collected Wislawa Symborska or the collected Bill Manhire, but I’d want to not have read them before, I’d want them to be a discovery. A new collection by either of them, I suppose, but I’d want it to be hundreds of pages long.

Auckland University page

Pingback: Friday Poem: Anna Jackson’s ‘Afraid of falls?’ — a pinhole in the dark expanse of memory to let the light of childhood through | NZ Poetry Shelf

Pingback: Anna Jackson’s I, Clodia and Other Portraits – A lightness that is fierce, a spareness that is complex | NZ Poetry Shelf

Pingback: Poem Friday: Anna Jackson’s ‘Scenes from the photographer’s childhood: wardrobe’ — Within that silent beat, poetry blooms | NZ Poetry Shelf

Pingback: Poetry is off to Menton | NZ Poetry Shelf