Poetry Shelf review: A Game of Two Halves: The Best of Sport 2005 – 2019

Leave a reply

A Game of Two halves: The Best of Sport 2005 – 2019, ed Fergus Barrowman

Victoria University Press, 2021

This book looks back through the fifteen issues of Sport from 2005 to 2019. In 600 pages it presents fiction, poetry, essays and oddities by 100 of our best writers, from leading lights like Bill Manhire, Ashleigh Young and Elizabeth Knox, to emerging glow worms like Tayi Tibble, Ruby Solly and Eamonn Marra. (Blurb)

Reviewing A Game of two Halves is a sad glad day for me. I have loved reading my way through old favourites but I am also sad that this is a farewell. I can remember how excited I was when the first issue of Sport hit the bookstands. It was fresh, exciting, unmissable. I am pretty sure I have every copy stacked on my study shelves. On the blurb, I read that editor Fergus Barrowman’s A Game of two Halves selection is a mix of ‘leading lights and glow worms’, the established and the emerging. Light is such a good analogy because I often find myself using the word ‘incandescent’ to describe writing I love. Writing lights me the reader, the world at large and in miniature, the present, future, past, the miraculous things words can do. Even when the subject matter is dark, shadows and weirdness loom, writing still lifts. Sets me alight. This is what literary journals can do. This is what Sport has done.

All those clothes it turned and churned, the lint

that trapped in its door. I once thought

many things would make my life happier

and now one by one I will let them go.

Rachel Bush from ‘All my feelings would have been of common things’

Confession – I haven’t read the whole volume yet but I can’t wait to do that to share. I am so engaged, I want you to place A Game of Two Halves on your summer reading pile as a go-to source of luminous writing. Last ‘light’ analogy I promise. Reading the poetry (I always start with the poetry) is like tuning into a Spotify playlist where individual tracks resonate and then send you back to the albums. Rachel Bush’s sublime ‘Thought Horses’ sent me back to that collection. Michele Amas’ equally sublime ‘Daughter’ sent me back to After the Dance. Herein lies the first joy of Fergus’s playlist. I am reconnected with poems that have registered as all time favourites. Read Angela Andrews’ ‘White Saris’. Bill Manhire’s ‘The Schoolbus’. Read Ruby Solly, Esther Dischereit, Rebecca Hawkes, Ash Davida Jane, essa may ranapiri, Tayi Tibble, Michael Krüger, Jane Arthur, Chris Tse, Freya Daly Sadgrove, Emma Neale. Read Amy Brown’s ‘Jeff Magnum’. Ashleigh Young. Louise Wallace.

This is the place where the schoolbus turns.

The driver backs and snuffles, backs and goes.

It is always winter on these roads: high bridges

and birds in flight above you all the way.

The heart can hardly stay. The heart implodes.

Bill Manhire from ‘The Schoolbus’

Perhaps the biggest gleam is from Tina Makereti’s prose piece, ‘An Englishman, an Irishman and a Welshman walk into a Pā’. I am such a fan of her novels, rereading this reminds me of the power and craft of Tina’s writing.

This is the way of it. Before I have memorised her in a way that will last forever, my mother is gone. If someone asks me to recite my first memory, which consists of chickens in a yard and an old farmhouse and an outside toilet, it will contain this absence. For the rest of my childhood, I don’t think it matters.

Tina Makereti from ‘An Englishman, an Irishman and a Welshman walk into a Pā’

In his introduction, Fergus tracks the development of Sport, the almost demises, and the decision to close (with regrets!). He mentions the vibrancy of the issue Tayi Tibble recently edited (Sport 47, not just the cover but also the contents) and ‘whether it made sense to go on reinventing Sport every year?’ I have appreciated the move to showcase Aotearoa writers beyond the traditional Pākehā set in recent years. To always draw upon the inspired writing of new generations. Fergus closes off his introduction by mentioning a couple of other anthologies VUP / THWUP are doing and then offers this: ‘And after that? You tell us? Send us your ideas. Send us your work.’ Exciting prospect.

I raise my glass to toast what has been an important venue for new and established voices. I will miss Sport. I will really miss Sport. Thank you Fergus and Victoria University Press / Te Herenga Waka University Press for dedicating time and love to a vital space for readers and writers. I look forward to what comes next.

It has been a long time

since I last spoke to you.

When we were children, our fathers

wanted to be mountains

our mothers were the sky.

So here I am, the dry hands,

steady in fog, waiting by the not-there

trees, the holes birds make

in the air.

Jenny Bornholdt from ‘It Has Been a Long Time Since I last Spoke to You, So Here I Am’

the air is thick with depression

even the flies fly very slowly

Freya Daly Sadgrove from ‘Pool Noodle’

I worry about whakamā and imposter syndrome paralysing our people, making them too afraid or inhibited to really live their best lives or at least the best lives they can under the hellskies of capitalism and party politics. I’m all about people, and I’m all about the best lives.

Tayi Tibble from ‘Diary of a (L)it Girl or, Frankenstein’s Ghost Pig’

Fergus Barrowman has been the Publisher of Victoria University of Wellington Press since 1985, and founded Sport along with Nigel Cox, Elizabeth Knox and Damien Wilkins in 1988. He edited the Picador Book of Contemporary New Zealand Fiction in 1996.

Victoria University Press / Te Herenga Waka University Press page

Poetry Shelf celebrates 2021: Ruby Solly picks books

Tōku Pāpā, Ruby Solly, Victoria University Press, 2021

On Friday I am posting book picks (and more) by a group of authors who wrote or produced something I loved this year. I am posting Ruby Solly’s separately as it as a longer piece. Ruby’s debut collection, Toku Pāpā, was one of my favourite poetry reads of the year. In my review I say:

Enter a poetry book that catches your heart and every pore of your skin, and you enter a forest with its densities, its shadows and lights, canopies and breaths, re-generations. You will meet oceans and rivers and enter different ebbs and flows, different currents, fluencies. You will reach the sky with its infinite hues, dreamings, navigations, weatherings (storm washed, sunlit, moonlit). You will meet the land with its lifeblood, embraces, loves, whānau, anchors.

This is what happens when I read Ruby Solly’s Tōku Pāpā.

Full review here

Ruby Solly’s picks

I have found a phenomenal amount of comfort in books, music, films and art these last several years as many of us have. I was an avid reader as a child and would spend days reading (often bunking school to do so in one way or another, sorry Mum) but in these last few years I’ve seen other people use books in the same way more often. For travel from a still point, understanding, and most importantly, to see themselves reflected. I think of the origins of the word mokopuna; our selves reflected in a spring, fresh and new in the telling.

Perhaps selfishly, the strongest book related memory in my head for this year was the launch of my book Tōku Pāpā from VUP now THWUP. It really showed me why I write; having all my whānau there from all the different facets of my life, and my Dad speaking about how lucky we were to have such a great relationship formed around te ao Māori and te taiao. There were a few points where there wasn’t a dry eye in the house, and I think I would have won the award for wettest face in the whare. It was a real highlight as well to be able to fill Unity Books with the sounds of taonga pūoro, I like to imagine those sounds seeping into all the books, and the space still feels different when I go there now. A book can be healing, a book can be rongoa.

Another top moment was essa may ranapiri reading a poem to a track by taonga pūoro practitioner Rob Thorne at ‘Ngā Oro Hou’ as part of ‘Oro’ at Auckland Writers Festival. Just the way that breathing is so integral to both the music and the words in a way that marries and melds the two. Being there felt like an almost out of body or inter atua experience; I felt like breath personified, Hinepūnui-o-toka.

I absolutely adored Anne Kennedy’s The Sea Walks Into A Wall and rushed to get it as soon as it came out from my local, the fantastic Good Books owned by writers Jane Arthur and Catherine Robertson, and staffed by writers such as Eamon Mara and Freya Daly Sadgrove. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone look sad in Good Books! Anne’s writing has been a long standing love for me since I read Sing Song in my teens. This new book plays with the written form as the sea plays with shape of the coast; in a skillful way that moves and shapes us new lands to play on.

Greta and Valdin by my humour idol, Rebecca K Reilly, was a major read for me this year. I don’t think I’d ever read a book of young queer Māori who were allowed true happiness, reading a happy ending and a whānau of understanding felt very healing in a way where the healing never got in the way of what is a fantastic story. ‘Rangikura’ by Tayi Tibble served as karakia, as haka, and as whakatauki for me. Prayers wishing for peaceful waters to navigate in astronesian waka, rousing stories to pep us up for battle, and lessons learnt through experiences that Māori readers can now learn in words instead of pain and if they do not learn, Tayi will still be here writing them home to themselves.

The birth of We Are Babies Press is something I’ve found incredibly exciting too, as well as the hub that is Food Court Books. I feel like every year is a good year for the work of Jackson and Caro; Wellington’s writing Fairy God Parents. Going in to Food Court Books to hunt for treasures has been a treat this year, and it’s so beautiful to see Food Court Books and We Are Babies grow.

It surprises me, but even in these times, I feel lucky. I feel lucky to be writing and reading in a time of change, in a time where the affected are who tells the story, in a time where the fight is moving us forward. In a time where there are not only moments of struggle, but moments of joy and fun, because that’s what we all deserve. Moments of peace, moments of joy, and moments of deeper understanding of how we move and relate to the world. Wishing you all a very safe, meaningful, and beautiful 2022, may your pages be turning and your cup always be half full.

Ruby Solly (Kāi Tahu, Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe) is a writer, musician and taonga pūoro practitioner living in Pōneke. She has been published in journals such as Landfall, Starling and Sport, among others. She is currently completing a PhD in public health, focusing on the use of taonga pūoro in hauora Māori. Her first book, Tōku Pāpā was released by VUP in 2021

Ngā Oro Hou: The New Vibrations

The AWF programme announced this event: ‘An exceptional evening performance that brings together celebrated writers and taonga puroro practitioners in a lyrical weaving of language and song. Writers Arihia Latham, Anahera Gildea, Becky Manawatu, essa may ranapiri and Tusiata Avia joined poet/musicians Ruby Solly and Ariana Tikao. The session was curated by Ruby as part of her Ora series.

“The words were heart penned. I sat in the front row and breathed in and out, slowly slowly, breathing in edge and curve and pain and aroha and sweet sounds. It was like being in the forest. It was like being in the ocean. It was like being wrapped in soft goosebump blankets of words and music that warmed you, nourished you, challenged you. This is the joy of literary festivals that matter. This warmth, this love, this challenge.” Paula Green

Poetry Shelf Monday Poem: Kiri Piahana-Wong’s ‘In liminal time’

In liminal time

It’s been ten days and

I have this sense of being mired in time

I look at the clock, look away again,

for what feels like a long time

But when I look back, the hands haven’t moved

No time has passed at all between

looking away and looking back

And yet a world of time has gone by

I know that inside me something has blossomed

and ended and all the while

the hands of the clock are locked

while I float in liminal time

and yet I keep existing in the world

My breath tied to the second hand, tick, tock, tick, tock

It’s amazing, isn’t it, how when we fall asleep,

we just keep on breathing, almost nothing can stop it

At night, I keep imagining that I am lying facedown

in my parents’ fishpond

I have an image in my mind, of

my long dark hair floating on the water

A small part of me that isn’t grief-stricken

observes that my Ophelia complex is

alive and well, even if my father isn’t

I occupy my mind thinking about Ophelia’s father,

who was killed accidentally by Hamlet, a man

his daughter loved. Who was Ophelia’s father? His

actions seem to indicate he cared about his daughter,

but he was after a political match. Weren’t they all

in those days. Before Ophelia died,

she handed out flowers — she gave herself rue.

Rue is bitter, but it has the power to heal pain. It

signifies regret. She was trying to tell herself

something, even if she didn’t know it

At night, there are so many stars

I once read that if you have insomnia, you should count the stars

until you fall asleep,

so I count for a while. I don’t fall asleep, I just lose focus

I stare at the stars until I’m falling into them

and continuing to look at them hurts too much

Because they are bright, and remote, and I am alone

Kiri Piahana-Wong

Kiri Piahana-Wong is a poet and editor, and she is the publisher at Anahera Press. She lives in Whanganui with her family.

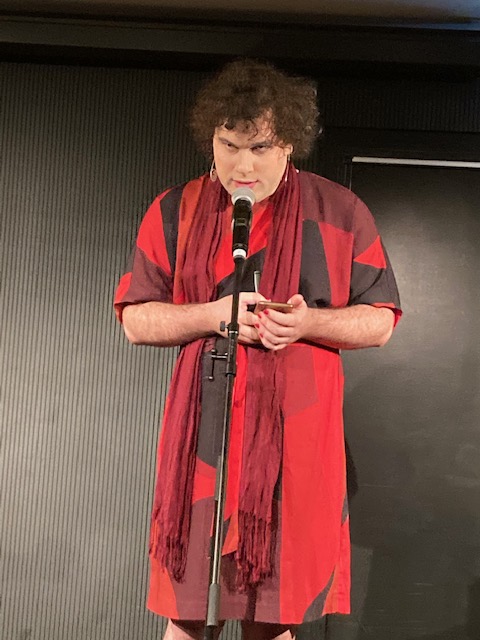

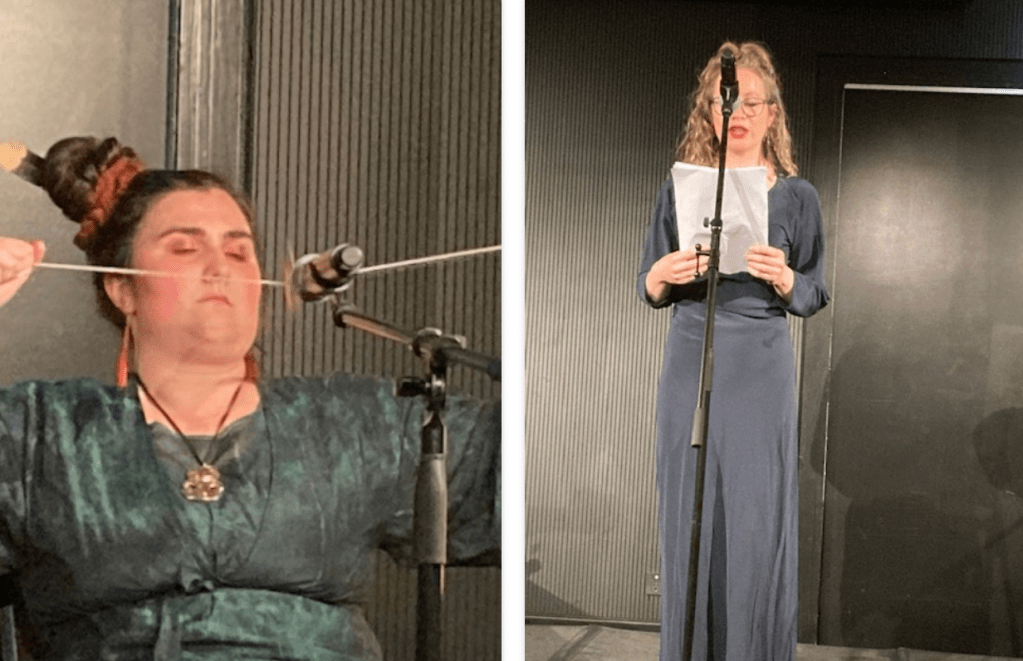

Poetry Shelf review: Out Here: An anthology of Takatāpui and LGBTQIA+ writers from Aotearoa

Out Here: An anthology of Takatāpui and LGBTQIA+ writers from Aotearoa,

eds Chris Tse and Emma Barnes, Auckland University Press, 2021

Gender buttons

An object on a shelf; a self with words inside that never came out.

Your finger down my spine; fine singing in my bones. Umbrella avoiding

the rain: the celebrating hat you wear. Tell me a little more about myself.

The food you forgot; what you got for biting at my breasts. The coloured

loss of uneaten toast on the bench and your tongue of loving pepper.

Hunger heavy in my mouth.

This room we bed down in, be wed down in. White roses growing

on the ceiling.

You want in a variety of colours, but a rose is a rose is a rose

a bunch of them placate the air much better than one.

We couldn’t grow anywhere else.

The teasing is tender and trying and thoughtful. Melting without mending

you undo my gender buttons till all of me is myself.

Hannah Mettner

Out Here is a significant arrival in Aotearoa, both for the sake of Takatāpui and LGBTQIA+ writers and readers, and for the sake of poetry. The sumptuous and wide ranging anthology feeds heart mind skin lungs ears eyes. It is alive with shifting fluencies and frequencies, and I want to sing its praises from the rooftops, from the moon, from street corners.

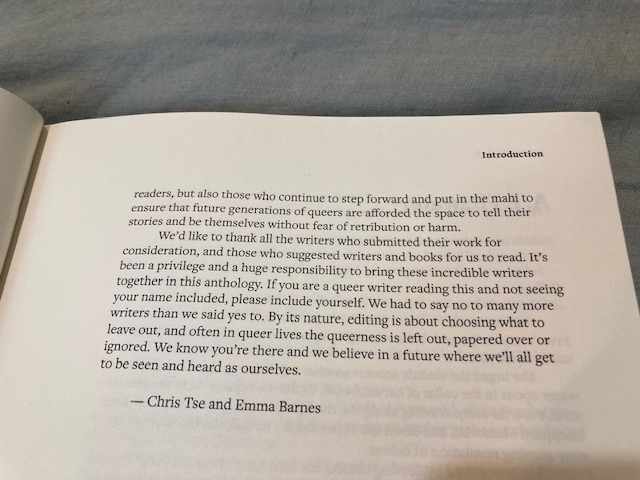

Chris Tse and Emma Barnes have responded to the erasure of queer identities in a national literature that was traditionally dominated and controlled by white heterosexual men. Chris and Emma opted to use ‘Takatāpui’ and ‘LGBTQIA+’ in the title to signal Aotearoa’s rainbow communities within the broadest possible reach. They have used the word queer in their introduction and underline that that must make room for as many ‘labels and identities’ as necessary. I am using the word queer with similar intentions.

Having spent a number of years on a book that responded to the erasure of women in literature across centuries, I understand what a mammoth task it is to shine a light across invisible voices and to reclaim and celebrate. To refresh the reading page in vital ways. Out Here draws together prose and poetry, from a range of voices, across time, but it never claims to cover everything. We are offered a crucial and comprehensive starting point. After finding 110 writers, Emma and Chris sent out an open call, and the response was overwhelming.

We chose words that delighted us, surprised us, confronted us and engaged us. We chose political pieces and pieces that dreamed futures as yet only yet imagined. We chose coming out stories and stories of home. We followed our noses. What our reading revealed to us is that our queer writers are writing beyond the expectations of what queer writing can be, and doing it in a way that often pushes against the trends of mainstream literature.

Emma Barnes and Chris Tse

I am reading the poetry first. I am reading poetry that reactivates what poems can do whether in terms of style, voice, theme, motifs. Some poems are navigating sexuality, gender issues, sex, love, identity. Other poems explore the body, oceans, discomfort, the end of the world, mothers, fathers, violence, tenderness, place, the dirt under fingernails. Expect humour and expect seriousness, the personal and the imagined. Expect to be moved and to be heartened. Some of the poems are familiar to me, others not, and it is as though I have parked up in a cool cafe for a legendary poetry reading (if only!). The physicality is skin-pricking, the aural choices symphonic, the intimate moments divine.

Take the three poems of Ash Davida Jane for example. I am reminded of the feminist catchphrase the personal is political but I am upending it to become the political is personal. ‘Good people’ resembles an ode to the soy milk carton. The poem considers how to be in the world, to make good choices, and be a good person when the world is drowning in plastics. It blows my head off. Ash’s second poem, ‘water levels’, celebrates the tenderness of being in the bath with someone who is shampooing your hair. The poem slows to such an intimate degree I get goosebumps. A poem that looks like a paragraph, ‘In my memory it is always daytime’, pivots on the waywardness of memory, its omission coupled with its power to transmit. I keep stalling on this glorious suite of poems rereading, revelling in the ability of poetry to deepen my engagement with the world, language, my own obsessions, weakenesses.

I stall too on Carolyn DeCarlo’s poems like I have struck a turning bay in the anthology. Rereading revelling. Reading revelling. And then Jackson Nieuwland’s astonishing ‘I am a version of you from the future’ where they stand in the shifting shoes and choices of a past self and it is tender and it is moving and it is tough. Or Ruby Solly’s ‘Lessons I don’t want to teach my daughter’, which is also tender and moving and tough. The ending in both English and Te Teo Māori restorative.

Imagine me standing on my rooftop singing out the names of the poets in the anthology and how they all offer poems as turning bays because you cannot read once and move on, you simply must read again, and it is measured and slow, and the effects upon you gloriously multiple. Chris and Emma have lovingly collated an anthology that plays its part in the final sentence of their introduction:

The final sentence resonates on so many levels. No longer will we tolerate literature that is limited in its reach. Poetry resists paradigms set in concrete, fenced off manifestos, rules and regulations, identity straitjackets. I welcome every journal and event, website and publishing house, that opens its arms wide to who and how we are as writers and readers. Out Here makes it clear: we are many and we track multiple roads, we are familied and we are connected. We are loved and we are at risk. We are floundering and we are anchored. This is a book to toast with a dance on the beach entitled POETRY JOY. I am dancing with joy to have this book in the world. To celebrate its arrival, I invited nine contributors to record a poem or two. Listen here.

Thank you Emma, Chris and Auckland University Press; this book is a gift. 💜 🙏

I would like to gift a copy of this book to one reader. Let me know if you’d like to go in my draw.

The editors

Chris Tse (he/him) was born and raised in Lower Hutt. He studied English literature and film at Victoria University of Wellington, where he also completed an MA in creative writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters (IIML). Tse was one of three poets featured in AUP New Poets 4 (2011). His first collection How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes (2014) won the Jessie Mackay Award for Best First Book of Poetry and his second book He’s So MASC was published to critical acclaim in 2018.

Emma Barnes (Ngāti Pākehā, they/them) studied at the University of Canterbury and lives in Aro Valley, Wellington. Their poetry has been widely published for more than a decade in journals including Landfall, Turbine | Kapohau, Cordite and Best New Zealand Poems. They are the author of the poetry collection I Am in Bed with You (2021).

Auckland University Press page

Poetry Shelf celebrates 2021: Emma Neale picks favourite books

The Pink Jumpsuit, Emma Neale, Quentin Wilson Publishing, 2021

Rather than do my annual list where I invite loads of poets to pick favourite books, I opted for a much smaller feature. I have invited authors whose work I have loved (a book of any genre, a poem, a website) to share favourites. No easy task as I have read so many books I have loved in the past year: poetry, fiction, nonfiction, children’s, local and international. On Friday 17th I will post the feature but, between then and now, I am posting some authors who have produced longer contributions.

Emma Neale’s collection of short fictions is one of my favourite reads of the year. In my short review, I wrote:

Any book by Emma Neale underlines what a supreme wordsmith she is. At times I stop and admire the sentences like I might admire the stitching of a hand-sewn garment.

Like Emma free-falling into memory, sideways skating after looking at ‘Wanderlust’, I am free-falling and sideways skating with this glorious book. I am free-falling into the power of truths, diverted by fiction, the dark the light, the raw edge of human experience, and this matters, this matters so very much.

Emma Neale, a Dunedin based writer and editor, is the author of six novels and six collections of poetry. Her most recent collection is To the Occupant (Otago University Press). In 2020 she received the Lauris Edmond Memorial Award for a Distinguished Contribution to New Zealand Poetry.

Emma Neale’s Picks

Poetry

I’m disoriented when I realise how few full poetry collections I’ve read this year. Lockdown, and then major surgery, altered my reading habits more dramatically than I was aware of until I sat down to look at my (scrappy) reading journal. I feel a bit like the dreamy kid who hasn’t done all her homework: there are so many 2021 titles that I haven’t managed to read yet. But books should last so much longer than their year of publication, shouldn’t they?

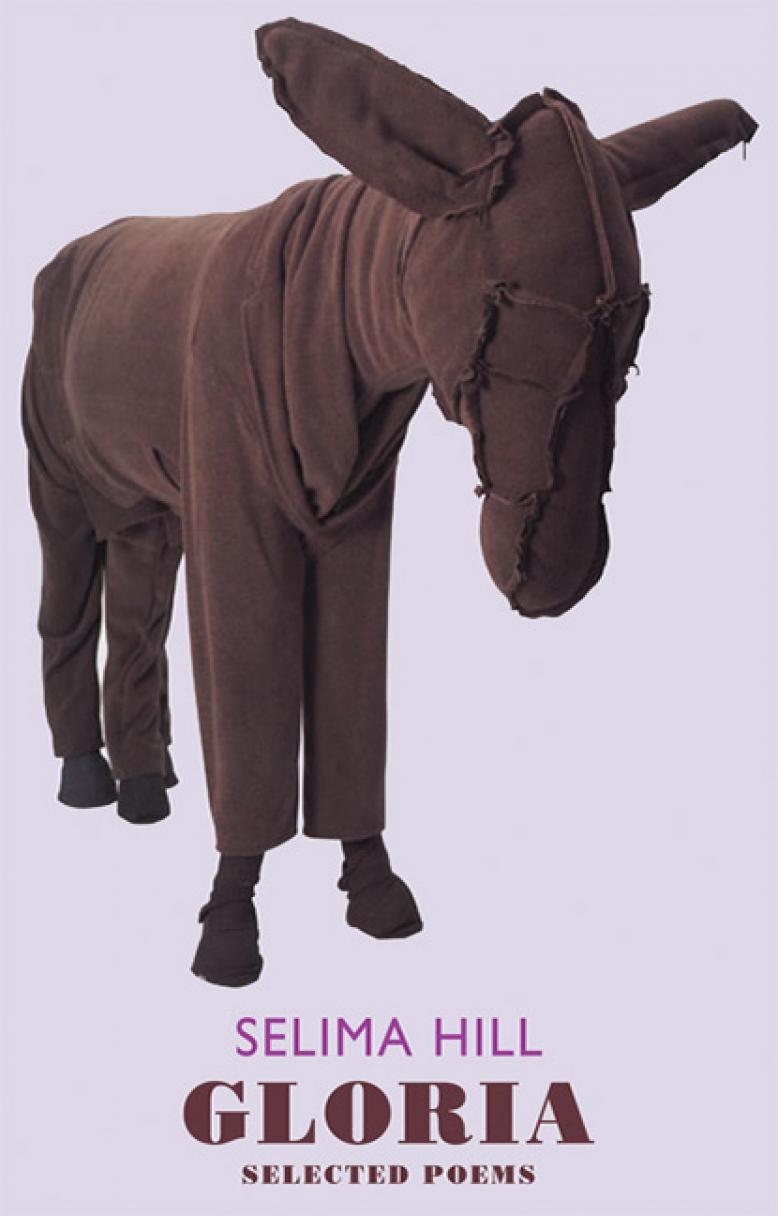

Selima Hill’s Gloria: Selected Poems (Bloodaxe Books) stands out, for its gorgeously bewildering fusion of the surreal, the direct, the subversive and sharp; she writes tiny, acid drop poems that sting you awake with their dark and often tragic accounts of male-female relationships and family, and their sardonic skewering of contemporary consumerist culture.

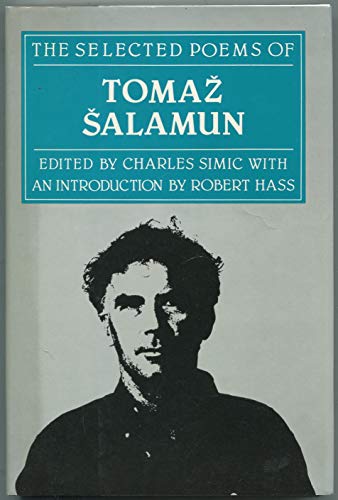

The Selected Poems of Tomaž Šalamun – edited by Charles Simic (The Ecco Press), with an introduction by Robert Hass, was a new discovery for me: I ordered it on the strength of the opening poem ‘History’ – which is wacky, subversive, swerves from apparently self-aggrandising to irreverent and bitterly self-mocking with rapid, comically dislocating speed.

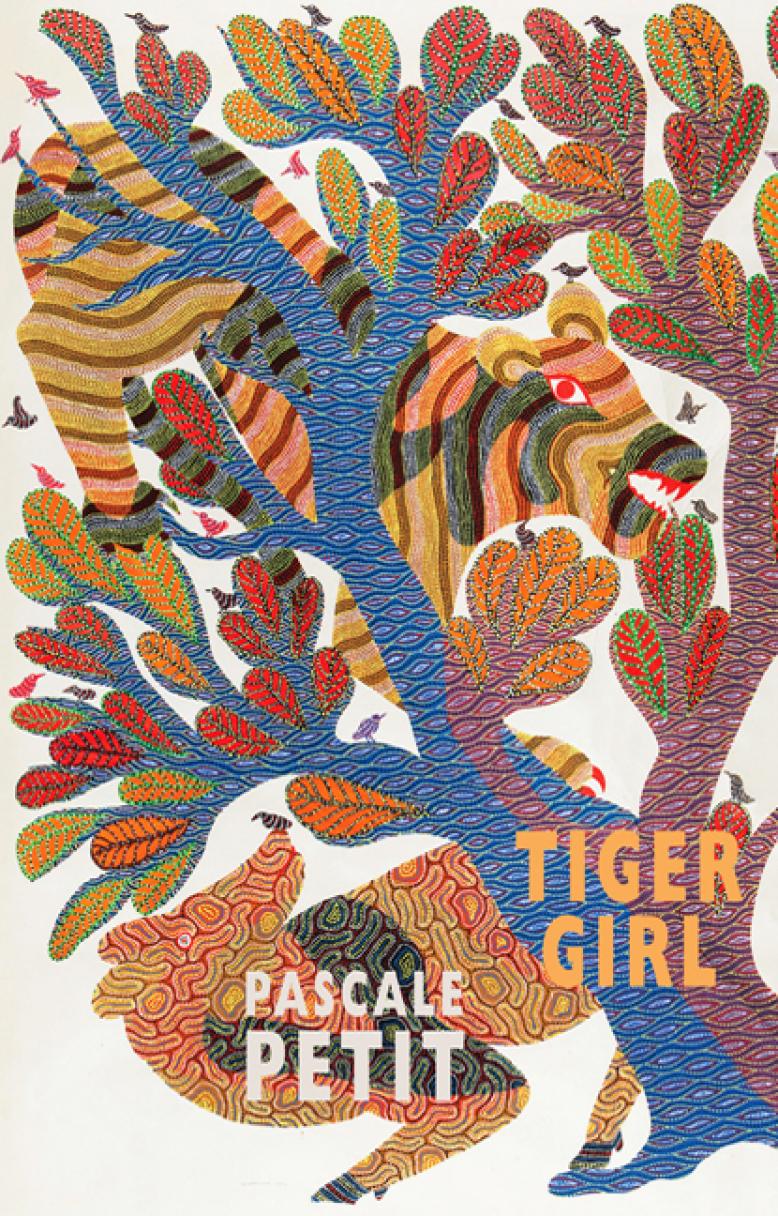

Pascale Petit’s Tiger Girl (Bloodaxe Books) in which many poems explore her grandmother’s Indian heritage, and the natural world in subcontinental jungles, was a delight to read, as her work is exuberant with metaphor and simile, even when she deals with grim psychologically tough material. I feel like she is a bit of a soulmate poet, as she doesn’t necessarily agree that less is more. Lush is more, here, and there are times I just want to soak up to my chin in the warmth and prismatic light of this generous, capacious voice.

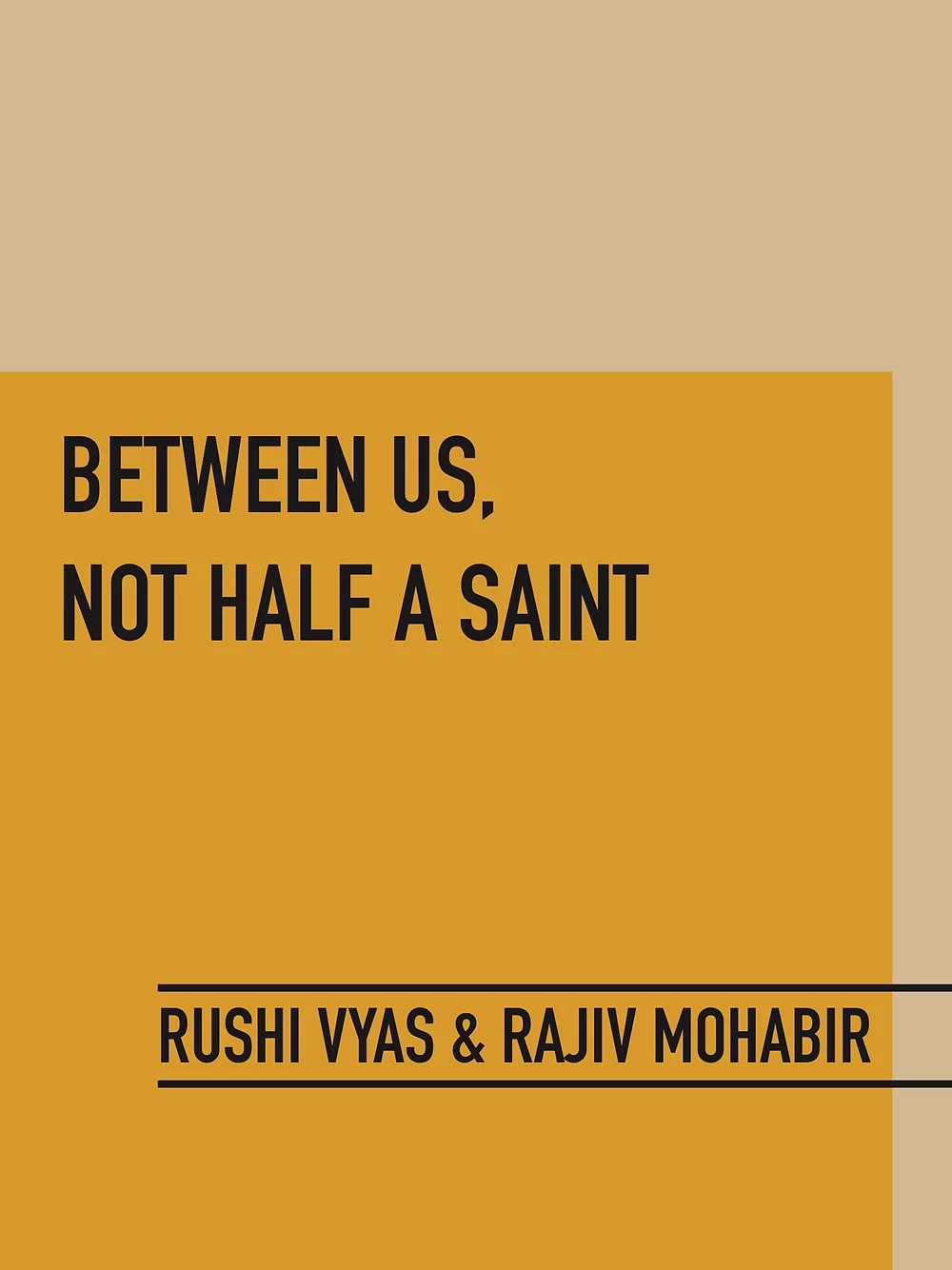

Between us Not Half a Saint, co-authored by Rushi Vyas and Rajiv Mohabir (Gasher). This collection astonished me with its discipline, the dialogue between the two poets, the way it manages to embrace the political and the spiritual; how well the dialogue about responsibility, power, identity, territory, belief, self vs ‘community’ operates.

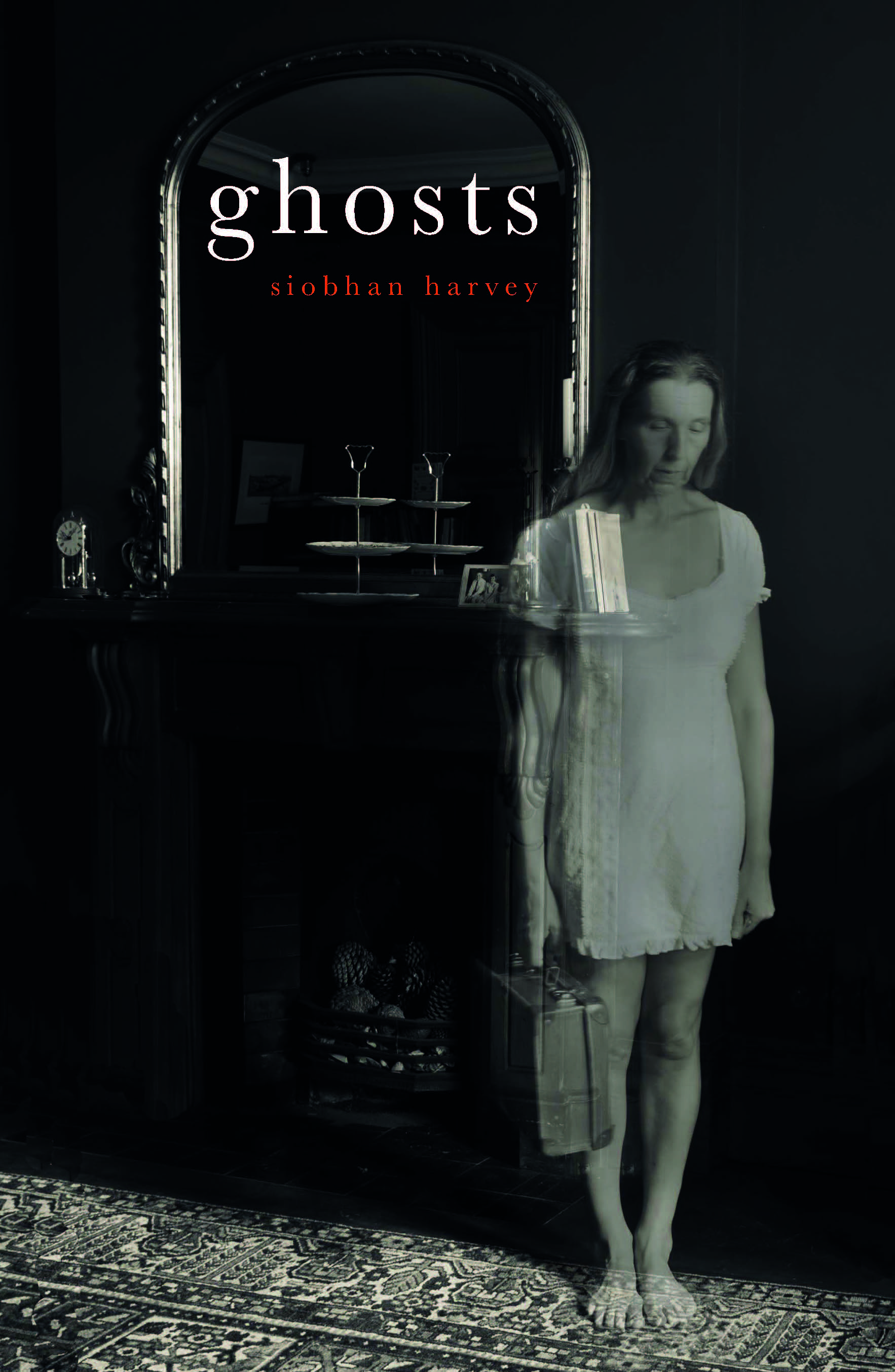

Siobhan Harvey’s Ghosts (Otago University Press) was an intellectually and emotionally challenging editing job I was lucky enough to work on; the poetry often stretched the ‘literal-minded’/logic-tracking compartment of my editing brain while we were at the dialogue stage of author-and-editor; and I think (I hope!) it made me a more open reader. The final book, which includes a profound personal essay, is intensely philosophical, and another striking achievement from the author of Cloudboy.

Prayers for the Living & the Dead by Lindsay Rabbit (SP) was a refreshingly sparse, quiet, and reflective collection: somehow it helped to still the babble, clamour, the torrent of words from other non-literary sources pouring in to my head and home this year.

The Wilder Years: Selected Poems by David Eggleton (Otago University Press) – as I said at the Dunedin Writers and Readers festival event on the politics of poetry: David’s work ranges from the piercingly lyrical, to epic postcolonial tsunamis of language, that exhibit a zany abundance of imagination and, I think, an extraordinary capacity to hold wild contraries together, in work that often has the spring and salt of satire. The poems condense such a vast general knowledge, comment on so many social phenomena, that often when reading his work I’ve thought, ‘David is basically the internet’.

I’m still reading both How to Live with Mammals, by Ash Davida Jane (VUP), and Rangikura by Tayi Tibble (VUP). In the first, I’m enjoying the interleaving of vulnerability, humour, intriguing facts slipped in like quick sparkles of energy, a youthful spritz and yet a piercing nostalgia for the planet as it once was, a filmic sense of what it’s like to be young and in love and still frightened of how it all trembles on the brink of loss and collapse. With the second, I’m finding it shares some of the qualities of Ash Davida Jane’s work, and yet the unpredictable power dynamics of desire, the history of imperialism, colonialism, and the dance of contemporary and mythic references are a bright, looping needle-and-thread running through it all.

Bird Collector, by Alison Glenny (Compound Press) seems both somehow more humorous and more absurd than The Farewell Tourist, yet it still has a kind of atmosphere of loss and melancholy. Elliptical answers to elusive questions; nostalgia for an impossible past; large tracts of knowledge erased; definitions from a dreamlike dictionary; the melancholy of lost, exquisite creatures, moments, and even of self-recognition …. this collection is intriguing. As I’ve said elsewhere, ‘it reads as if a Victorian composer, carrying her valise of new operetta libretti, collided in the street with a watchmaker, his briefcase of sketches for a new time-keeping device, and a genderfluid astronomer toting the patent forms for a mechanised orrery made of blown egg shells and bird skulls. Their papers, shuffled together by misdirected desires, unspoken and even unconscious intentions, lead to an entirely new work — a sheaf of pages where the negative space of silence speaks as pressingly as the shape of song.’

Bird Collector increases the absurd humour and the sense of literary pastiche found in The Farewell Tourist, as it both flirts with voices of disembodied wisdom and scholarship, and exposes so much of what is surreal in human behaviour, by creating an alternative, credible epoch and society that seems bound by strange rules, to contain weird and uncanny juxtapositions, yet is as riven by unpredictable desires and sudden disappearances as our own. A plangent strain of loss might rise from the pages: yet when we wake from their trance, we’ve seen such entertainingly strange and marvellous things.

Prose

I’ve written elsewhere about how much I Ioved Charlotte Grimshaw’s The Mirror Book (Penguin), and Doireeann Ni Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat (Tramp Press) this year; both psychologically profound and lyrically composed books, which explore the construction of identity, and the sometimes subtle (but often glaringly overt) cross-tides of internalised and institutionalised misogyny. They variously examine narcissism, parenthood, motherhood, marriage, and in Ni Ghríofa’s work, the erasure of women’s experiences historically: in the sense that archival records of their lives, in the past, weren’t kept as clearly or as diligently as those of men. The books are very different stylistically, yet in my mind, they mirror or ghost each other.

Another memoir that I rate really highly this year is Deborah Levy’s Real Estate (Penguin), for its exploration of ideas of independence and motherhood after children have left home; singledom after a long marriage; and the politics of heterosexual relationships. One of the paragraphs that beams out illumination runs:

Is it domestic space, or is it just a space for living? And if it is a space for living, then no one’s life has more value than another, no one can take up most of that space or spray their moods in every room or intimidate anyone else. It seems to me that a space for living is more gendered and that a space for living is more fluid. Never again did I want to sit at a table with heterosexual couples and feel that women were borrowing their space. When that happens, it makes landlords of their male partners and the women are their tenants.

Local fiction that I’ve lost myself in this year includes Sue Orr’s intricate, sensitive, thoughtful Loop Tracks (VUP); some of the quiet, elegant stories in Elizabeth Smither’s The Piano Girls (Quentin Wilson Publishing), others in Tracy Slaughter’s The Devil’s Trumpet (particularly the extended piece published as the novella-in-flash, If there is no shelter) (VUP) and Kirsten McDougall’s comic eco-thriller, She’s a Killer (VUP), which I’m celebrating for its tense and ominous cameo from a blissfully unaware-yet-also-wary four year old, towards the end … argh!!! Do not drink strong coffee immediately just before this scene.

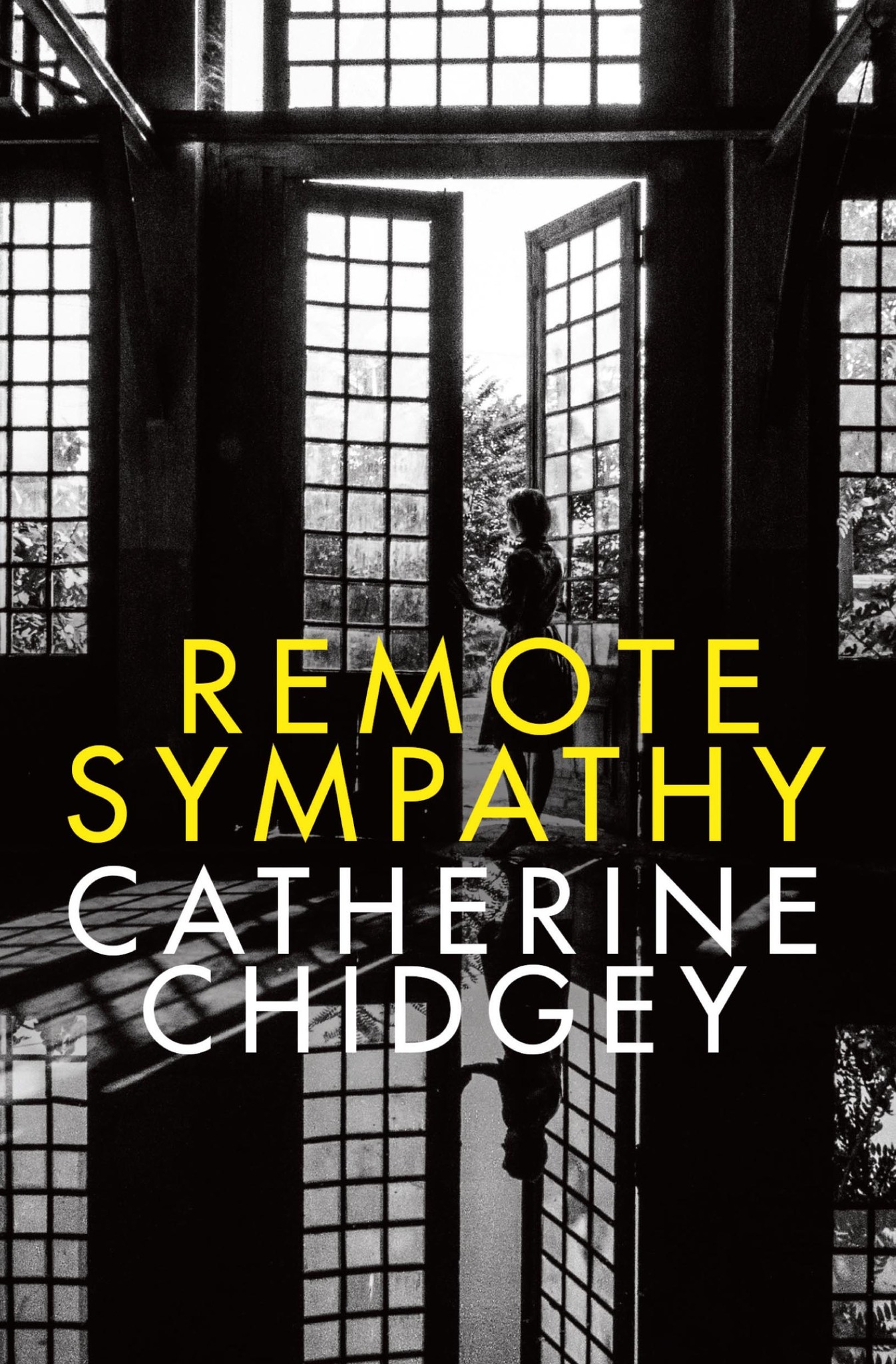

I came late to Catherine Chidgey’s Remote Sympathy (VUP), which was published last year: but it absolutely knocks it out of the book-park for me in terms of New Zealand fiction I’ve read lately. It’s skilfully constructed, managing several different narrative voices; it somehow deals with traumatic, terrifying cruelty with a superlatively light hand, which enables us to keep looking at the heart and mind of evil. Chidgey has a gift for choosing the right metaphor or simile to encapsulate a situation at exactly the right moment: the way she balances plot and poetry is exquisite for the reader. For me as a writer, it makes me want to throw up my hands and quit and yet at the same time it makes me want to work even harder. It’s a bittersweet confusion to have.

I’ll limit my raves to two other novels I read this year. One is David Vann’s Halibut on the Moon (Text Publishing), an immensely strong fictionalised version of the last days of his father’s life before he committed suicide. It is a remarkable achievement, as we want to keep reading, even though the main character’s actions and desires are often deeply repellent. There’s such compassion in the narrative, somehow, and I found myself comparing it to the unlikeable narrators in two other books I read this year: Eileen, by Ottessa Moshfegh (Penguin) and First Love by Gwendolyn Riley (Allen & Unwin); both books I failed to engage with fully. I think Vann’s novel is so effective because we see all the other characters in Jim’s family so clearly struggling with him, and trying to bring him back to some kind of moral centre. The way Vann handles a painfully direct, honest, bitter, revealing conversation between the suicidal Jim, and his lifelong-monosyllabic father, is cooly devastating, for the way it pulls in massive unspoken, suppressed intergenerational trauma for indigenous (Cherokee) people.

Oh really only one other rave?? Okay, Susanna Clark’s Piranesi (Bloomsbury). A wonderful, crisply written, strange fantasy about a character who lives in a mysterious labyrinth that contains various classical marble statues, and whose vast chambers fill and drain with ocean tides. He is trying to piece together his own identity through reading shredded notebooks and trying to recall the oblique dialogues he has with the one other inhabitant of the labyrinth. At one point I thought perhaps the labyrinth was the delusion of a man terrifyingly trapped by another man … but … if I say any more, I will tear and mangle the magic for other readers.

Poetry Shelf celebrates 2021 in books: Three Booksellers make picks

Recently I drove into the city and went to the Women’s Bookshop and Time Out Bookstore. Carole Beu was out so I missed walking around the shop with her and getting top reading picks. I scooped up some new books and it felt crazy good to browse. At Time Out I had an inspired book chat with Manon Revuelta, got tips from manager Jenna Todd and came away with novels by Sigrid Nunez, a novelist new to me, and a Nina Simone biography. The following day I watched Carole’s regular video spot on Facebook (I love this ongoing feature) and bought the children’s books she was recommending in an instant (Dragon Skin is also a pick below!). It felt like I was back in the shop browsing with her.

Over the past four months, books, podcasts and tv series have been my ticket out of lockdown gloom and anxiety. Add in cooking, jigsaw puzzles and gardening, along with writing and blogging, well life has been surprisingly good. I have had numerous deliveries from the excellent Good Books in Wellington, and love how they add a message or drawing, plus what the staff member is reading. I can now add Auckland bookshops to my delivery mix again, and risk rare trips to the city. Books have been my anchors, hot-air balloons, sweet escape hatches.

Driving home to the west coast – where we have had myriad places of interest, covid hot spots, gun battles and deaths, devastating floods, local destructive conspiracy theorists – I am amazed by my capacity for happiness. Books are a key thing – the fact I’ve been reading and writing intensely. Usually I post a mammoth list of 2021 poetry picks by a mammoth list of poets but decided that was too much this year. Instead I’ve invited authors who have written or produced something that I have loved to bits to share picks (posting next week).

BUT FIRST: Secondly and selfishly, to make up for missing physical bookshop visits, I invited The Women’s Bookshop, Time Out Bookstore and Good Books to share 2021 picks. Any genre. Any place. Any time. I pictured myself walking down the aisles as they gave me some top tips. As a high risk person whose vaccinations may not work as well, I am so very grateful to my online bookshops – and to your safety measures when I recently visited. Thank you.

The Women’s Bookshop Carole Beu

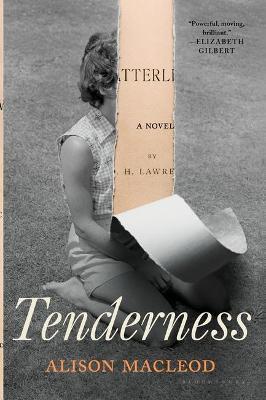

Tenderness – Alison McLeod (Bloomsbury $35) This epic, absorbing novel is fascinating for anyone interested in literature & politics. It’s a book about a book – Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the repercussions down the decades of it being declared an ‘obscene’ book. The important people are all there and are vividly drawn – D H Lawrence & Frieda, Katherine Mansfield &Middleton Murray, Rebecca West, E M Forster – – and Jackie Kennedy thirty years later when Hoover is trying to stop it being distributed in the USA. It’s about imagination and freedom, brilliantly written and full, yes, of tenderness.

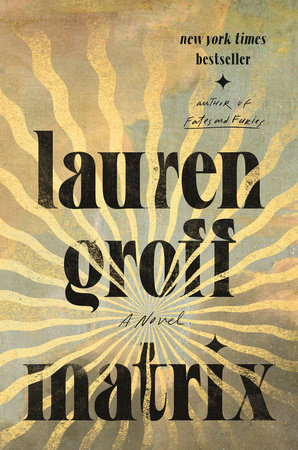

Matrix – Lauren Groff (Penguin Random House $35) Marie, tall, ungainly and wild, is not suitable for the court of Eleanor of Acquitaine. She is banished to a remote, run-down Abbey, which she spends her life transforming. She blossoms into a brilliant leader, eventually becoming the Abbess, fostering the talents, passions and creativity of the women in her care. They become powerful, self-determined, and in our modern terms, extremely feminist! It’s an inspiring and exciting read.

Good Books Jane Arthur

Michelle Langstone’s debut essay collection, Times Like These (Allen & Unwin, $37), is an invigorating, sensitive book that made me look at my world with more wonder. Each time I’ve sold it, I’ve been so excited on behalf of its new reader – and I’ve had terrific feedback from lots of them (including you, Paula!) thanking me for the suggestion, which isn’t something that happens that often. I’m a cynic at heart, but these earnest, loved-filled essays melted even me. I’ve read 50 books since Times Like These so I figure it must be special if it’s still with me this strongly.

For younger readers, Dragon Skin by Karen Foxlee (Allen & Unwin, $23) is, no exaggeration, a perfect book I reckon. My colleague Freya and I both read it and whenever we talk about it, we clutch at our hearts! It’s gentle and compelling storytelling, about a 10-year-old named Pip, who is dealing with some pretty heavy stuff in her life (family violence, grief, loneliness – but don’t let this put you off; it’s all done with a beautifully light touch). Then she finds a tiny dragon, languishing in the dust of her Australian town. The book could be summed up with a statement like, “Pip saves the dragon but she also saves herself”, but it’s so much more than this and utterly rewarding to read. This is a terrific book to give sensitive eight to 11-year-olds but since it’s probably my favourite book of the entire year, full-stop, if you’re a grown-up like me, you should read it too.

Time Out Bookstore Manon Revuelta

A book that really stood out for me this year was a tiny little memoir called Sempre Susan, by Sigrid Nunez (Penguin, 2015, $26). Nunez became a close friend of Susan Sontag after being hired to type up her letters in the 70s, and was also in a relationship with her son, David Rieff, for several years. They all lived in Susan’s Manhattan apartment together—a weird setup, but an incredible vantage point. Nunez looks back to that time and paints an intimate picture of the Sontag she knew, and in the way of truly interesting memoirs, a multi-faceted person takes shape: at times exasperating, at others endearing. Always dedicated to her work. The observations of her character are so intricate, they can only come from a place of love: some that have stayed in my mind include a particular green coat Susan wore for many years (the holes in the armpit seams were only visible when she hailed a cab from the sidewalk), or a joke she surprisingly found hilarious (“have you taken a bath?” “No, why – is there one missing?”). Banal yet so revealing. By proxy, we get such a lovely sense of Nunez too, from her shy and impressionable youth to her reflective and solitary older self. More than a portrait of a literary icon, this is an inspiring meditation on the art of memoir and memory, gritty love, friendship, and the writing life. I only wish it were longer!

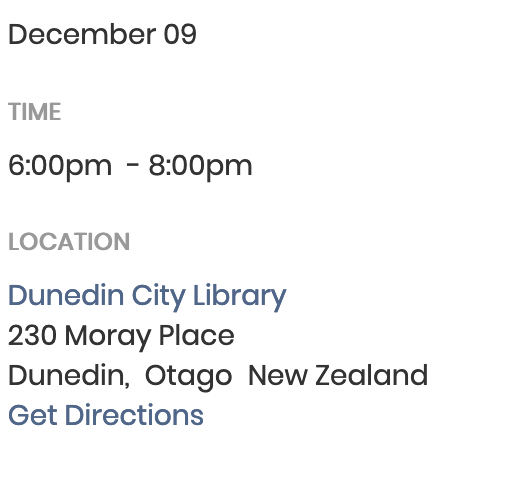

Poetry Shelf noticeboard: Celebrating National Poetry Day

Immerse yourself in the joy of poetry, as we enjoy a late celebration of National Poetry Day, and present the Shape Poetry competition awards.

Our special guests this year include:

Majella Cullinane – Lynley Edmeades – Sophia Wilson – Richard Reeve – Carolyn McCurdie – Emer Lyons – Megan Kitching – Liz Breslin – Emma Neale – Jenny Powell – Kay McKenzie Cooke – Michelle Elvy – Victor Billot

Diane Brown MC

With music by the Bill Martin Jazz trio

Awards presented by competition judge: Carolyn McCurdie

This is a FREE event, but PRIOR BOOKING IS ESSENTIAL

The format of this event has been changed due to COVID restrictions. If you have a ticket to the earlier format of this event, we will arrange for your ticket monies to be refunded to you

Presented by Dunedin Public Libraries in partnership with Otago-Southland NZ Society of Authors and Dunedin UNESCO City of Literature with the support of Phantom National Poetry Day and University Bookshop Otago

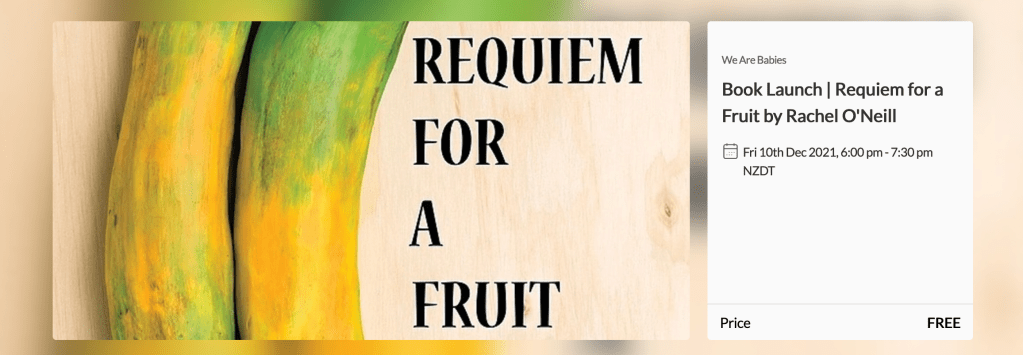

Poetry Shelf noticeboard: LAUNCH FOR Rachel O’Neill’s Requiem for a Fruit

Event description

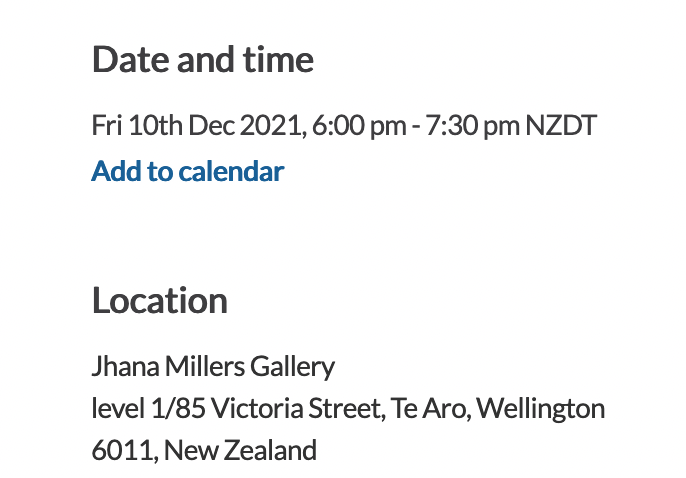

We Are Babies and Jhana Millers Gallery would like to welcome you to the launch of Rachel O’Neill’s second poetry collection, Requiem for a Fruit.

Requiem for a Fruit continues Rachel’s exploration of the form of prose poetry, to astonishing results. The poems in this book cast a slant lens on the everyday, opening up a world of possibilities and curious characters. With imagined and real dialogue, these characters converse and live as fully on the page as they would in the known world. O’Neill covers topics from love to interstellar travel, from the domestic to the absurd. Here are dowagers and dogs, a robot mother, husbands hiding behind fire trucks, and families made of stone. The landscape they populate is without reason, yet full of fruit.

Registration for this event is required so please register here for a free ticket. Our capacity for safe distancing is 40 people. Vaccine passes will be required. You can enter from 6pm, we will check your ticket at the gallery entrance and you will be asked to sanitize your hands and scan the QR code. Manual contact tracing also available. There will be copies for sale before and after the speeches and Rachel will be happy to sign them for you. There will be no food or drinks available under current alert level restrictions.

Poetry Shelf Noticeboard: The 2022 Kāpiti Writers’ Retreat

The 2022 Kāpiti Writers’ Retreat

25 – 27 February 2022

Waikanae, New Zealand

Immerse yourself in writing and conversation this summer. There’s something for everyone–whether you’re new to writing, an established writer, or somewhere in-between.

The Kāpiti Writers’ Retreat is happening from 25 -27 February 2022 on the beautiful Kāpiti Coast north of Wellington. This three-day gathering for writers encompasses intensive morning workshops, lively discussions and space to write, relax and engage with topics critical to your work.

Writers Practice is delighted to host leading writers from across Aotearoa – Chloe Lane, Gem Wilder, Helen Lehndorf, Nic Lowe, Rebecca Priestley, Sinead Overbye and Therese Lloyd – at the 2022 Kāpiti Writers’ Retreat. Each writer will teach morning workshops: in fiction, poetry, essay and responding to our current reality. In the afternoons, they will lead discussions on topics pertinent to craft and literature in Aotearoa.

You’ll find community, encouragement, and a safe place in which to take artistic risks.

Find out more here