The Venetian Blind Poems, Paula Green, The Cuba Press, 2025

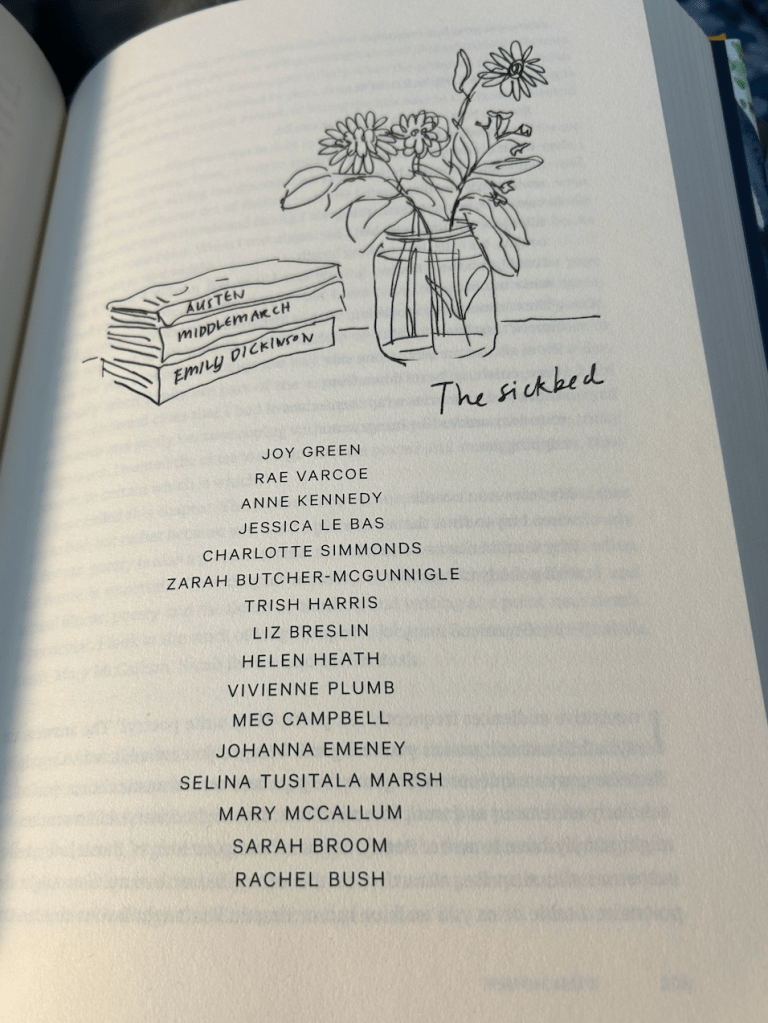

When I wrote Wild Honey: Reading New Zealand Women’s Poetry (MUP, 2019), I built a house, dividing the book into rooms, and then moving through open doors and windows to the wider world. The book was neither a formal history nor a theoretical overview of New Zealand’s women’s poetry but a way of collecting, building recouping valuing the poetic voices of women in Aotearoa. As I moved through the rooms in the house the themes accumulated: politics, poetics, love, the domestic, self, relations, illness, death, location, the maternal, home, voice.

The book came out in 2019, not that long ago, and I was interested to read ‘The sickbed’ chapter again. I began the chapter by saying inquisitive audiences often ask, ‘Why write poetry?’. I still claim the answers are myriad: it makes us feel good, we are addicted to wordplay, we can squeeze writing a poem in between domestic chores, parenting, scholarly endeavour, work commitments. We might crave public attention, awards, good reviews. We might simply have to write. Our poetry might reflect a love of music, storytelling, suspense, wit, surprise, attraction to the unsayable or beauty. We might write poems at the kitchen table, in our head as we walk, run, dream or dillydally. We might favour condensation and pocket size writing or expansion and long sequences. We might write from a sick bed.

My collection Slipstream (AUP, 2010) came out of my breast cancer experience. I refer to it in Wild Honey: ‘poetry was an energy boost, a way to enhance my sense of wellbeing’. As I wrote, at least a year after the experience, I did not feel I was writing poems – nothing on the page earned the label ‘poem’ in my view — but I was conscious that the white space, the juxtapositions, the assembled lists and the melody were reaching for the poetic. I did not want to summon the dark, middle of the night slumps, but rather to show illness can change the way you see the day as well as live the day.

The Venetian Blind Poems is a little different in that I wrote it in the moment, in hospital and then back home on the recovery road. But I recognised similar motivations to write.

My new collection has been out in the world for a fortnight now, and it feels so very special. To be in Motutapu Ward and the Day Stay Ward this week, signing copies for nurses, hearing them read fragments aloud, reminded me that poetry is an incredible way of connecting. I am still in a thicket of appointments as I fine tune the road ahead, but this fortnight feels like like my time in hospital, when so many poets sent me a poem in a card. The emails you have sent me these past two weeks, so thoughtful and caring, have shone fresh light on how and why poetry is a gift. On why we write and sometimes publish poetry. I will treasure your emails for a long time (and reply soon)!

More than anything, The Venetian Blind Poems is a way of saying thank you to the doctors and nurses who have given, and are giving so much. I offer an enormous bouquet of thanks to Mary McCallum and Paul Stewart at The Cuba Press, for the beautiful book, and for inviting such terrific responses to post on social media by poets who have read it.

Now its back to normal transmission! I have new ideas for Poetry Shelf bubbling like my sour dough starter, manuscripts to finish, a treasury of books to review, emails to answer, a few more appointments, and most excitingly, I am ready to get my secret seedling idea off the ground: Poetry Shelf Goes Live. Yes! Soon I will be back in the world organising live poetry events around the country.

A cluster of illness poems

The waiting game

begins with someone calling your name before you

wait to have your blood taken in a windowless room.

Wait for the stultifying thoughts of red and disease

to pass. Wait for the phone call, for relief to wash

over you. And while you are waiting I recommend you

dance like the memory of sweat easing down his

throat; roll open like the drum beat of your limbs

in sync; tear through your wildest nights, still lit in

hopeful neon; cry like the Christmas you lost your

last grandparent; and sing like the forgotten violin

slowly coming undone in your muscle memory.

If you do not allow yourself to sleep in peace

with your worries, you will find yourself awake

at the bottom of a very deep, very secret lake.

Chris Tse

Turbine, 2014

A Final Warning

I walked past the stars

the silence of grandfathers

I was going somewhere but where

I went left at first then right

then way off course then back to somewhere

near the middle

did this mean I was ready to die

well they’ve been testing me for everything

I think I’ve got the lot

Bill Manhire

from Honk Honk, The Anchorstone Press, 2022

The Night Shift

I wake on the ward, afloat on ketamine, fentanyl,

see sky-blue morphine swifts roost nearby

in pleated paper thimbles

and some uneasy instinct tugs my gaze

to a scuff mark on the lino floor.

Coal-dark, it smolders. I stall.

A voice reassures me it’s just a graze

left by the wheel of some routine machine:

IV, PCA line, heart monitor screen.

Yet as I ease deep-cut core and leaden legs

over the distant side of the high bed

I can’t shake this need to stare

not quite in fear: not quite.

For last night, creatures came.

They arrived en masse, nodded, swayed,

pressed into each dimmed cubicle,

their copper eyes bright-candled,

lips pouched over strong, proud teeth,

their heads bowed in silent inspection;

marmalade lions with oxen feet,

crested birds with antlers, candy-pink teats,

all crowded, crowded round each bed

as the window in time was fast contracting,

and they wanted us to see before our minds

sealed tough with the fibers of logic, denial.

Their fur packed tight as green florets on catkins.

Their horns, colossal black spikes, gleamed like grand pianos.

Such mass and strength in their embedded weaponry,

yet still, they withheld their crush and maim.

The breath and bunt of their herded skulls

said we are the unbroken in you, don’t be afraid,

and I saw through the seep of dawn

that soon like guardians they will gather

each one of us, our failing forms absorbed

into their warm, strong-walled veins

until we too watch

each figure on the bed

as something invisible shifts

in the intricate balance of matter and spirit.

So it is awe, not dread, that asks me

to leave the ground undisturbed

where they gathered,

to skirt carefully the sign one left

like a scorched hoof print

as if they had stood in fire

to show they bear time’s pyre for us,

our wild sentries, our wild sentries.

Emma Neale

from Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit, Otago University Press, 2024

(A lifetime of sentences)

Soon, I could leave my body without prompts. The artist’s concept of the birth of a star, or I broke my name until the fibres separated and lost their coats. My thirst for windows kept me indoors. My gaze wandered across the suburbs of childhood, faces stammering with shyness, bodies masquerading as furniture. Initial mass and luminosity determine duration, but my sensibility comes to require an object. Here, the word “system” implies a level of certainty that is unwarranted. Some of those memories were not written by me, so they are memos, at home on my desk, but still authoritative. Now, instead of a pupil, there’s a screensaver. It was late. The room was empty. A lifetime of sentences which at first glance seem superfluous, but whose value is later understood. One thing leads to a mother. Soon enough, a flock of children came running and tapped on the glass. When I reached the bottom of the stares, I looked up.

Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle

selected by Kiri Pianaha Wong and was published a fine line and also Best NZ Poems 2011

it is a wedding cavalcade

in which I take your day of birth

and marry it with ten pink tulips

to mine look, behind us on the road

sadness and unutterable joy

leaping over the rocks

how we were those people in the crowd

unmindful of everything

except stepping along together

under our parasols

what’s wrong with that?

see, the road is still there

still ahead and behind

losing its mind and leaping

over the rocks with its train

of clowns who are careless

careless careless and will never

behave any differently

believing themselves arm in arm

with all they need

to sustain life on a distant planet

choogaloo, this is all you need

tulips and a parasol

to keep off the bigger bits of debris

falling out of the sky

don’t be sad

there is every chance

we are just now resident

in two minds regarding each other

tenderly, quizzically, uproariously

as a wedding cavalcade

Michele Leggot

from Milk & Honey, Auckland University Press, 2005

What’s the time, Mr Wolff-Parkinson-White?

Press palm against skin

feel its breathless sprinting

count 230 beats in a minute

count six sibling arguments

count four gecko squawks

gulp two glasses of water

phone the absent dad three times

return to the couch

count 194 beats—and whoah

with the flutter of a moth

it slows down to a jog

steady rhythm of 75

Fire heart

Sea heart

Earth heart

Calm waters as a child

now more fire than earth

chased by a white wolf

Want to feed my child

ruby corn raspberries

red meat cherry tomatoes

pomegranate bursts

sugar and acid

enough to woo a rebel

The heart heals itself

between beats, reassures

Elizabeth Smither

Mikaela Nyman

Amy Marguerite picked a poem from Shira Erlichman’s Odes to Lithium, a book I now have on order! But sadly I didn’t manage to get permission to post the poem but you can listen to Shira read it here.

Self-Affirming Mantra

I was searching my symptoms online. Disturbed sleep led to fatigue which led to post-viral condition and also to alcohol abuse and liver disease and unthinkable cancers which all led to conclusions about society and how one operates in it, how someone can be rational and maladaptive at the same time, how resilience is just a word in a PowerPoint, how years of work go into the manufacture of one unit of anxiety (a person), and how each unit, although similar to others in many ways, is unique, the product of a freakish and golden permutation of inputs, which led me back to my usual searches for wars and politicians and racing drivers and recipes and animals and islands and colours.

I went out into the day with my symptoms. The sun made the swans look like harps. I appreciated the silhouettes of buildings. I scrumped apples from over a fence. My symptoms were still with me but also not with me. I was loving them. I was setting them free.

Erik Kennedy

from Poto | Short (Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2025)

Paula Green in conversation with Anna Jackson

A collage conversation with nine poets

The Cuba Press page

Poetry Shelf Live! Yes!

LikeLike

Love love love my copy. Beautiful, stalwart poetry capturing moments and time’s gifts plus a record of pain and toughness.

LikeLike