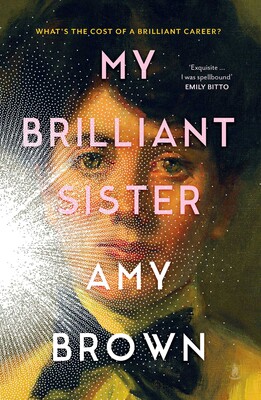

My Brilliant Sister, Amy Brown, Scribner/Simon & Schuster Australia, 2024

Amy Brown’s debut adult novel, My Brilliant Sister, is a brilliant, insightful read with deftly crafted sentences and structure. Witty. Warm. Nuanced. It was the perfect book to devour over the past weeks, and underlines the strength of novels to get us thinking and feeling within and outside frames, to reflect on where we are and where we‘ve been, particularly as women.

Perhaps the reason it has resonated so deeply with me is because my doctoral thesis in The University of Auckland’s Italian department explored the writing of Italian women novelists, considering the ink in their pens from every direction possible, their silencing and their resistances, their preferences and their attachments. I ended up with the word ‘conjunction’ because it clearly signalled women, and in my thesis writers, can neither be determined nor regulated by models and expectations but form an enriching and necessary movement of ‘and’. We are this and this and this and this – whatever our gender.

Amy’s novel is a version of Stella Miles Franklin’s My Brilliant Career (1901), a novel that features the rebellious sixteen-year-old Sybylla Melvyn. Living in the Australian Outback, Sybylla rebels against the social strictures placed upon women, fuelled by those demanding rights and voice across the globe.

I am picturing Amy’s novel as a glass globe. It builds vital form though a series of layers that can be admired independently, but that work together to form a whole, a narrative object say, that depends upon conjunctions.

There are three narrative sections with three women protagonists in three different settings. ‘Ida’ is set in the present and features the voice of a mother/ writer/ teacher on the verge of rebellion. ‘Stillwater’ is set in the past and features the voice of Linda, Miles Franklin’s sister. Linda lives in the shadows and margins of her famous sibling. ‘Stella’ is set in the present and features the voice of a contemporary musician and songwriter who has retreated to an off-the-grid bach to reboot.

I hold the novel globe before me, and it sparks with light and intricate possibilities. Each voice is a refraction of Miles Franklin and her character Sybylla, a version of the three women protagonists, and a refraction of who I am as a reader. More than anything, it promotes the prismatic possibilities of women.

Character is utterly paramount, the voices shaped by Amy’s imagining, research and experience. Ideas are also paramount. Miles Franklin was a bohemian, a rebel, and stereotypes, whether women’s roles, placement in the margins, writing expectations and reception, are at the fore. I jotted down so many ideas in my notebook that got me sideways drifting.

Ida: To play is to pretend, but it is also real. The more realistic the pretence, the better the play. To play is to trick yourself into entering the real by appearing to escape from it, though the best games don’t give you time to think about them in this way.

Linda: My memory skims like a stone, hitting the surface of what happened at its worst moments and gliding above the months that must’ve been tolerable.

Linda: Words can, as everyone knows, be a form of nourishment. The best, like breastmilk, inoculate against the myriad contractable ills of the world.

Linda: This realisation urged me to write – to find any scrawlable instrument & begin telling my own story in the margins of your letter, however badly it came from my head in the moment.

Stella the musician: I can never remember the difference between average, median and mean, but I do recognise balance and I understand that it requires time.

Linda: At my side are birth, death, domestic labour, death; at yours, sea-bathing, freedom, success. Between us, we’ve lived a real life.

Many readers of the book have highlighted the interplay of intimate detail and wider focuses, a narrative texture that enhances its rewarding intricacies.

More than anything, the novel feels utterly real, not a reductive formula on creativity or domesticity, on how to define ‘women’, on either or. Yes, I am haunted by this book, I am inspired by this book, I am comforted by this book, because we are still writing, we are still communicating, mothering, going solo, inventing, breaking ceilings, changing laws. We are still loving, we are still stretching, discovering, rebelling. This brilliant book is to be shared.

With so much to say about My Brilliant Sister, so much I have not said, I invited Amy to respond to some of the questions that percolated as I read.

A conversation

Paula: I am a big fan of your poetry Amy. What changes when you shift from poetry to fiction?

Amy: Thank you, Paula. I think the transition from poetry to fiction has been gradual and subtle for me. My poems got longer – The Odour of Sanctity was, essentially, a 240-page poem. They gained prose footnotes (Neon Daze). They have always contained characters. And some of the fiction I was reading while writing My Brilliant Sister had a poetic texture – an emphasis on voice, unconventional plotting, symbolic weight, space for the reader to infer and play. Some that I remember particularly are Jenny Erpenbeck’s The End of Days, Jenny Offill’s Weather and Dept. of Speculation, and Claire Louise Bennett’s Pond. I think it’s only now that I’m writing my next novel – and conscious that I’m supposed to be writing a novel – that the process feels different, more deliberate.

Paula: Your novel depends upon both research and imagining. What were the challenges and the delights of this fertile braid?

Amy: Each has its own challenges and delights, as you say! I find the administration of research challenging; even after having done a PhD, I’m still quite hopeless at organising my notes, keeping track of sources and so forth. I lose quotes and berate myself and have to start over. And there’s often the sense of being overwhelmed by the responsibility of writing about those who’ve actually lived. But the thrill of dealing with primary sources – especially with historical voices – spurs me on. It was only when I read Linda Franklin’s reply to Stella’s parcel of My Brilliant Career that I thought I’d have a hope of writing my own novel; I needed to hear her written voice. On the other hand, the fact that Linda’s life was tragically short (she died of pneumonia when she was 25) and much less public than her sister’s meant that source material was limited, leaving space for me to imagine, speculate and relate.

Paula: Your three narrative sections juxtapose past and present: ‘Ida’ (present), ‘Stillwater’ (Linda, past), ‘Stella’ (present). Three different narrators, three different settings. Yet the movement of motifs, ideas and personal challenges is vital. Overlap is producing both difference and similarity. We have shone various spotlights into the shadows of the past in order to pay attention to what and how women write. Do you think there are shadows in the present that we still need to attend to?

Amy: Yes, absolutely. In Australia (where I’m writing from right now), there’s currently an “epidemic” (as the Guardian described it) of violence against women. As of yesterday, 27 women have been murdered by men so far this year. A gender pay gap also persists (21% in Australia). These may seem tangential to writing, but how one lives obviously affects how one writes. If you’re living in fear, or working long hours (paid or unpaid), then writing is going to be difficult. That is largely what My Brilliant Sister ended up being about (as it seemed to me, at least, as I was editing it) – the fact that writing a novel, or making art, or having a brilliant career of any sort, requires support and care; it’s much more communal than the myth of genius suggests. Stella Miles Franklin herself – specifically her bequest in perpetuity – is responsible for supporting women’s writing in Australia. The Stella Prize, for women and non-binary writers, is a brilliant contrast to the societal “shadows” that still exist. It was established by a group of angry (and apparently slightly drunk) women in 2012, after several years of Australia’s most prestigious fiction prize, the Miles Franklin Award, being given to men.

Paula: I still see critics denouncing the personal and the domestic as banal subject matter in fiction and poetry. I have reviewed wonderful poetry collections in recent years that explore issues and experiences of motherhood, domesticity, the impulse to write and create, the open parameters of creativity, of writing, of being, of thought. I am thinking of your own poetry, Louise Wallace, Hannah Mettner, Anna Jackson, Emma Neale, Kiri Piahana-Wong, Karlo Mila, for a start. Domesticity and creativity are at the heart of your novel. Like a daily pulse, a necessary heartbeat, providing both tension and reward. What sparked you to explore these within a narrative?

Amy: I think this was in part due to my not being finished with the diaristic, deeply domestic voice I’d been using in Neon Daze (a verse journal of the first four months of motherhood). In fact, I wrote Neon Daze while I was stuck with the historical middle section of My Brilliant Sister, because I’d just had a baby and my mind had no capacity for research or crafting a fictional voice. Instead, I let myself meditate on my immediate experience. When I eventually returned to My Brilliant Sister in earnest in 2021 (five years later!), we were in the midst of lockdowns in Melbourne and that confinement (not dissimilar to the confinement of having a newborn) led me to focus on the minutiae of life at home. Aside from these circumstantial factors, I also really enjoy reading work that honours precise domestic detail.

Paula: In an interview you describe the effect of reading Stella Miles Franklin’s novel My Brilliant Career at a turning point in your life. Did her approach to writing nuance your approach to writing?

Amy: Stella Miles Franklin wrote My Brilliant Career when she was a teenager, which I think is evident in the audacity and energy of the narration. Sybylla, Stella’s autofictional protagonist, is at turns hilarious and earnest, insufferable and inspiring, which charmed me and certainly helped me shape her character in the middle section of My Brilliant Sister. More broadly, I think I was encouraged by Franklin’s own courage in attempting to broach large, genuine questions in her novel – in a way, both of our novels concern what it means for women to lead a good life.

Paula: Stella based one of the characters, Sybylla, on herself. Did you find yourself weaving autobiographical traces into your narrative?

Amy: Yes, I did. The first of the three sections was, initially, much longer and more autobiographical than it ended up being in the published version. It became clear to me during the editing process that, while aspects of my own life were necessary to the novel as a whole, a swathe of diaristic material in the opening section would not go with the fictional second and third parts. So, last year, I started from scratch and rewrote the first section completely and fictionally, which felt impossible at the time but wonderful afterwards. Instead of patchworking different fabrics together, there were threads of autofiction laced through a more tonally coherent whole.

Paula: The novel’s two contemporary sections are set in the time of Covid, and signal its restrictive and divisive settings. For some it was a time of personal reassessment, of renewed values. Covid is still with us, but we face other local and global catastrophes. At one point, Ida comments on how reading a book enables you ‘to inhabit the lives of others’, to divert you from daily concerns. In the middle section, Linda proposes words as a form of nourishment. How do reading and writing work for you in these difficult times?

Amy: As long as I can remember, reading has been a treatment of sorts for me. I prescribe myself what I feel I’m lacking or require more of. Sometimes what I read feeds my mood, other times it teaches me something about how I’d like to write, or it shifts my perspective. Or it helps me sleep. At the moment I’m reading Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional, about a woman who joins a convent in, it seems, a bid to escape a profound loss of hope. As a novel, it questions whether loss of hope is a moral failure. I think this is an enormously important question for the times we are living in. But, also, I am aware that while reading can be a source of hope and solace and empathy, it needs to be, as far as is possible, accompanied by action. I read and admired Pip Adam’s writing advice recently, which advocated for political activism and community engagement as writerly behaviours.

Paula: Have you read any books in past year or so that have haunted, transported, inspired, delighted you, as yours has me?

Amy: So many! I’ve had a blessed run lately. Here are a few favourites:

Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book haunted me with its perfect portraits of both youth and age, via six-year-old Sophie and her grandmother. It reminded me of my (of everyone’s) mortality in such a way that was more warming than chilling.

Lauren Groff’s The Vaster Wilds transported me to 17th century America with such visceral vividness that I still see it, involuntarily, most days. Weird but true.

Airini Beautrais’ The Beautiful Afternoon inspired me (as all of Airini’s writing does) for its intellectual heft and candour and goodness (for want of a better word).

Amy Brown is a New Zealand-Australian writer and teacher who lives in Naarm/Melbourne. She has published three collections of poetry, four children’s novels, and completed a PhD at the University of Melbourne. Her poetry, essays and reviews have been published in Australia and New Zealand. The debut novel which became My Brilliant Sister was shortlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Prize for an Unpublished Manuscript.

Simon & Schuster page

Pingback: Poetry Shelf newsletter | NZ Poetry Shelf