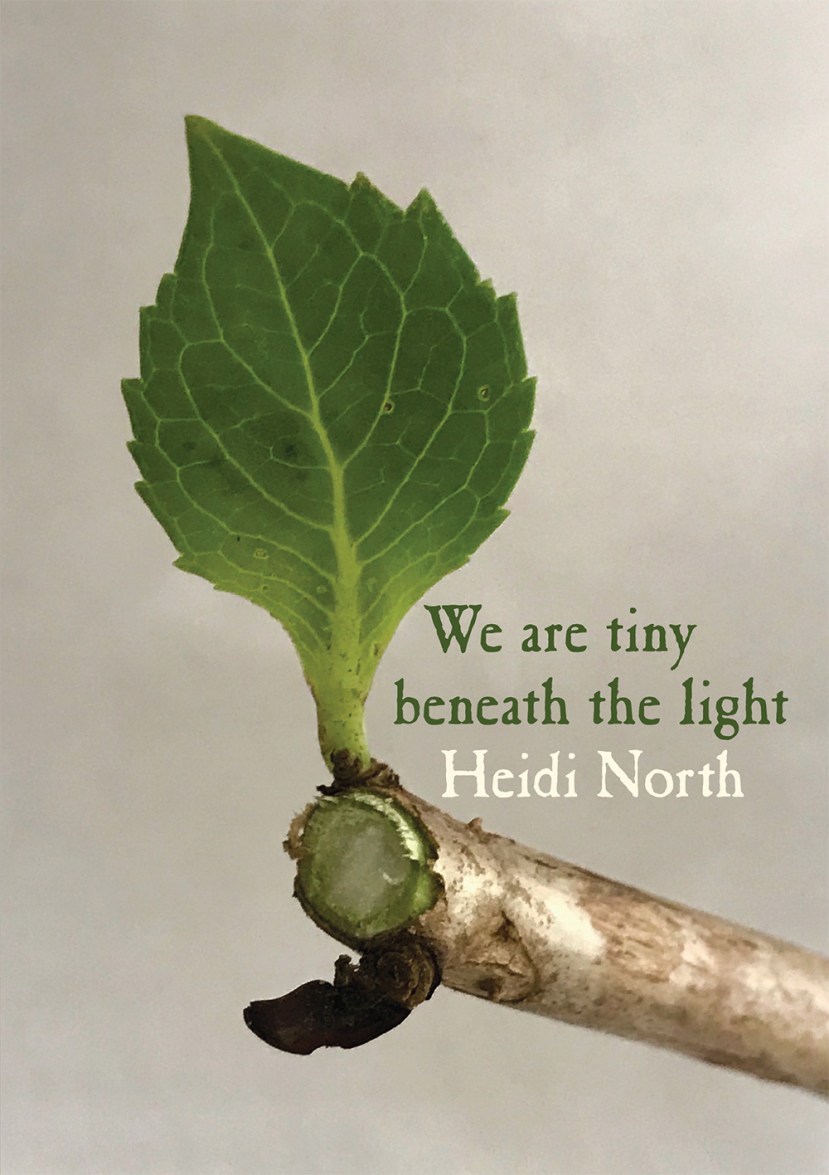

We are tiny beneath the light, Heidi North, The Cuba Press, 2019

Muscle memory

I don’t know how to let you go

into a future where you don’t turn

as if by muscle memory, as if by heart

to take my hand

I can still feel the beat under your palm

the dry square next to your thumb

crescent moons rise on your fingernails

the tiny red freckle sparking up

Heidi North, from We are tiny beneath the light,

Heidi North has won awards for both her poems and short stories, including an international Irish prize, and has published work in local and overseas journals. She was the New Zealand fellow in the Shanghai International Writers programme in 2016. She was awarded the Hatchette/NZSA mentorship to work on a novel and has a MA in Creative Writing from the University of Auckland. Her debut poetry collection Possiblity of Flight was published by Mākaro Press in 2015. U2 chose ‘Piha Beach, two years on’ from her new collection We are tiny beneath the light to screen at its Joshua Tree Stadium concerts in New Zealand. I find her poetry both economical and rich in effect, the self-exposure moving, the gaps equally significant.

Paula: I loved your debut collection Possibility of Flight. How do you look back upon that book?

Heidi: Oh thank you, that’s very kind of you to say. While I think there are things I would change if I published that collection today, I will always be fond of Possibility of Flight. It feels like a first book to me, in that I’d been working on some of those poems for a long time – some 10 years, so it felt so good to get them out there. This next book is quite different because it covers a relatively short space of time and I knew it didn’t have to contain the whole world. So they’re different collections. Possibility of Flight spans childhood, and leaving New Zealand to go on an OE to London, and ends with getting married and having a baby. Saying this, I realise you could read We Are Tiny Beneath the Light as a sequel of sorts.

Paula: Your new collection, with its evocation of both pain and joy, charts the end of a marriage. How difficult was it translating the private experience in poetic form and allowing it to go public? Does poetry aid the hard-to-say?

Heidi: I think that if I’d set down to write a book solely about the end of my marriage I would never have done it, but by working through the creative process and shaping the collection with my excellent editor and publisher, Mary McCallum at The Cuba Press, I allowed myself to be more vulnerable and go deeper, to strip away the poems that weren’t adding to this story, add in some more that did, and I let it become more of a narrative collection, which I think makes it stronger. I didn’t want people to think I was self-indulgent, and I didn’t want people to find it depressing. To counter that, I focused on the craft, and the book as its own entity, separate to me, and I hope that’s come through. But of course, there was a large part of me that was nervous to publish it – there is no escaping that this is an intense, personal book and I knew it was a risk. But yes, in general I think poetry aids the hard to say, and forces an honesty on ourselves as writer and reader that is at once liberating and terrifying. That’s the thrill of a poem.

There were three red apples

on the tree for weeks

and only today did you brave

the undercurrent of weeds

to find steady ground

to stand on to pick them.

from ‘Autumn’

Paula: Things matter gloriously in your poems. A window, dust, a rose, old photos, the sky resonate profoundly as I read and affect the way I inhabit a poem as reader. Were there particular things that you kept returning to? That were essential poem aides.

Heidi: There weren’t conscious things, but focusing on details, everyday things, is a way of dealing with the impossible. Poetry is a form of paying attention and slowing down. I use it to force to me do so, anyway – both when reading and writing poetry. When I think of myself writing this book, I have a sense of me grappling with the poems, they’re alive, wild and slippery, and I’m trying to button them down with concrete things rather than let them escape and run with the wind.

Paula: The three-section structure works well as you move from a specific place through despair and rupture to repair and joy. What effect did you want for the reader?

Heidi: I wanted to make sure I didn’t leave the reader in despair! Both because that’s an awful reading experience, and because that’s the truth of this story. I hoped to take the reader on a journey and that they would find grief and solace and joy in it, too. Because that’s the juxtaposition of life, isn’t it?

Paula: What are key things when you write a poem? When you read a poem?

Heidi: There’s the language, the musicality and muscularity of it. I want the poem to look right on the page. I spent a long time on that, the silence of a space, the punctuation – I could spend days on punctuation and how the words knit together – and I want to be startled and surprised with imagery. And I want all of this to come together with a clarity that feels like magic – I want to hear what the poem is singing and hear it ringing out clear. I don’t want the note the poem is sounding to be muddied with layers of complexity or cleverness for the sake of it. This is what I love reading in poetry and what I’m always aiming for.

The trouble

He’s wrapped his arms in muslin gauze

broken bird wings pressed close to his chest.

We pass without pecking

at the dried blood.

He’s been doing the washing in the communal machine.

He’s been doing a lot of that lately.

Heidi North

Paula: Did you read any poetry books that captured you as you wrote this collection?

Heidi: When I’m actively writing or editing poetry, I tend to stay away from reading too many other poets as it can influence me too much, but I came across Anne Michaels (she was at the Auckland Writers Festival in 2019) and when I heard her read I knew I needed to read more. She is an incredible poet and writer. Her collection, All We Saw, is so bold and unapologetically seeped in loss, and reading it gave me the courage to let We Are Tiny Beneath the Light be what it is – short, intense and quite raw. I often listen to music while I’m writing, often the same song over and over. For my first collection, Possibility of Flight, the song for that book is ‘England’ by The National and that was clear early on. This book took me longer to find the exact song, but in the end it is ‘Skin’ (live version) by Rag’n’Bone man.

Paula: Yes Anne Michaels was a festival highlight. I read all her books before she came and also especially loved All We Saw.

We Are Tiny Beneath the Light must have been a challenge. What kind of writing challenges do you see next?

Heidi: I have two novels kicking around and I think it’s time to finish them. One of them is a light-hearted novel about two sisters embarking on their OE to London and the other researched while I was in Shanghai on the Shanghai Writing Program in 2016, and wrote the bulk of while completing my Master’s at University of Auckland in 2017, with the inspirational Paula Morris. It’s the story of a runaway bride from Auckland who goes back to the last place she remembers being happy – Shanghai – after running out her wedding. Perhaps 2020 is the year to finish both of them!

From the top we survey our domain

the sand, the sea, those hills –

for an instant each soft blade

of tussock is picked out in brilliant sunshine

the world sharpened by tiny shadows

from ‘Burst’

Heidi North reads ‘The chickens’ from We are tiny beneath the light

The Cuba Press author page

Really enjoyed this! I like this, especially: ‘…focusing on details, everyday things, is a way of dealing with the impossible.’

LikeLike