A Surfeit of Sunsets, Dulcie Castree, Mākaro Press, December 2016

Dulcie Castree wrote short stories and poetry, before writing her novel, A Surfeit of Sunsets, in the mid 1980s. She had secured a publishing detail, the book was readied for publication, had an ISBN number good to go, but at the last moment, she withdrew the book due to editing challenges. Three decades later, her grandson Finnbar Castree Johansson, who lived in the same house and thought of his grandmother as a sibling, discovered the manuscript and decided to self publish it for the family. With the help of his aunties’ editing skills—Dulcie had four daughters—he produced a print run of 100. Dulcie, then in her nineties, died a few weeks before the novel was printed.

I got to see a taste of the novel online last year and I was captivated by what I read. Jane Parkin, an editor, and Mary McCallum from Mākaro Press, fell in love with the family edition, to the extent Mary reissued the novel in 2016. So much haunted me as I read the novel this week. Did Dulcie keep writing after she finished her first novel? Were her poems ever published (apparently her short stories were)? How old was she when she wrote the novel in the 1980s? Lynn Freeman interviewed Finn and Jane when the family edition came out last year, but has the book been reviewed? Does Dulcie, like Janet Frame, have a goose bath of unpublished poems? If so, are they any good? I have been haunted by the book, and I have been haunted by the woman who wrote it. Finn told Lynn that Dulcie’s failed publishing deal ‘screwed with her’ and she ‘didn’t write after it.’ She would have been in her sixties when she wrote the novel. What had she amassed leading up to that point?

I have scant answers to these questions, but I do have the novel, and Finn’s suggestion that the novel was ‘like an extension of her.’ Jane, who so loved the novel and scarcely had to change a word, saw the overriding voice as Dulcie’s. The novel is set in a small fictional town north of Wellington; there are the local residents and there are the Wellington escapees. Avid reader, Shirley has fled from an affair with a married man and a pregnancy termination. After the death of her husband, Poesy (Freda) has fled an empty house, with snobbish attitudes and a yearning to write poetry. Phoebe and Henry look after their niece May after the death of her mother. They, too, are Wellington exiles. There is an adult swimming group and a literary group that is more social than literary. You enter a fictional world brought to dazzling life through character and conversation. I am reminded initially of reading Virginia Woolf – of entering the long looping poetic conduit of her sentences where time slows and everything glows with life and feeling. I am reminded of Katherine Mansfield, and then again, Janet Frame. It is as though I enter a time that is both time-specific and out-of-its-time. For the most part you are becoming familiar with Shirley through her relations with the key residents, especially with May. Dulcie waits before revealing something about the child. It startles and sends me back to read her again. It is a curious thing the way you assume and presume as you read, and that the way we view people can be so constrained or biased. I am going to leave you the opportunity to discover May for yourselves. At the end of the book something dreadful happens that I did not expect.

What is particularly fascinating is how the novel swivels upon notions of poetry: the reading and writing and sharing of poems. May’s teacher thinks poetry is only suitable for children. Henry reads his sister-in-law’s poem notebook and finds unexpected and strange stirrings within himself. He doesn’t understand poetry but he hungers after it, searching for Felicity, and for himself, in the poems he reads: first, FT Palgrave’s Golden Treasury, then the Anthology of Twentieth Century New Zealand Poetry. He was born in England; he sees himself in one and then not the other, and then vice versa. Poesy hopes to ‘produce a poem, phoenix-like, from the ruins of her life.’ Francis, the other teacher, is composing a poem in his head, as though anybody can do it: ‘What a common thing poetry is.’ When he reads poetry, ‘he leaps straight into the pool of words like his belly-flopping boys and comes up dripping with joy.’ Poesy ‘persists in believing she can record the universe and beyond in eight rhyming rhymes.’ On the one hand, Dulcie delivers the portrait of a small town and the ripples effected by the summer gatecrashers, while on the other hand she builds a portrait of poetry, the way it is absorbed and borne and sung.

That the novel exudes an ethereal timelessness lures you in. The work resists narrative models, yet it offers a satisfying completeness, a voice that stitches you into a fictional world to the point you are part of it, as though you might give Poesy feedback on her poem. The sentences are both lyrical and lightly spun. When I finished reading I had that melancholy feeling you get at the end of a long summer holiday when the curtains are pulled, the bach door is locked, and you are beginning the long drive home, caught in an intertidal zone of freedom and routine, of drifting thoughts and daily chores, of different food and regular meals. Melancholic, too, because I am reminded of the shadows that women writers have occupied in New Zealand. I am haunted by this poetic book, and I want to peruse and pursue the threads that I have raised.

Author photo: Catherine Palethorpe

Radio New Zealand interview

Unity Book launch

Mākaro Press page

The launch of AS MUCH GOLD AS AN ASS COULD CARRY, by Vivienne Plumb with illustrations by Glenn Otto.

Friday 10 March, 6pm at split/fountain, 3C/23 Dundonald Street, Eden Terrace, Auckland.

Published by Split/Fountain

Split/Fountain page

I have gained much pleasure from reading the books on the long list. Of course – how can it not be?! – excellent poetry books did not make the cut. Take Chris Price’s glorious Beside Herself for example. I was transported by the uplift in Chris’s writing and celebrated it as one of her very best. I have said good things about all of the books because they gifted me reading experiences to savour. In my view, the long list was a go-to-point for the terrific writing that we are producing. I could not have picked four if I tried. I would have headed for the hills!

Boutique Presses are doing great things in New Zealand as are the University Presses, but in this showing, and with such noteworthy books appearing each year, and in quite staggering numbers, I am sendingsend a virtual bouquet of the sweetest roses to VUP. Three extraordinary books on the shortlist! Wonderful.

I adored the books shortlisted and will share my thoughts.

Tusiata Avia’s book is so rich and layered and essential. I have been reading and writing about this book in the past few months, and the more I read and write, the more I find to admire and move and challenge me. I wrote this after going to the launch:

Fale Aitu / Spirit House Tusiata Avia, Victoria University Press, 2016 (VUP author page)

Last night I drove into the city into some kind of warm, semi-tropical wetness —like a season that no longer knew what it ought or wanted to be — to go to the launch of Tusiata Avia’s new poetry collection. Tautai, the Pacific Art Gallery, was a perfect space, and filled to the brim with friends, family, writers and strong publisher support. I loved the warmth and writerly connections in the room. I have been reading Tusiata’s book on planes as poetry now seems to be my activity of choice in the air. I adore this book and have so much to say about it but want to save that for another occasion. I was an early reader so have had a long-term relationship with it.

the launch

The room went dark and an MIT student, bedecked in swishes of red, performed a piece from a previous collection, Blood Clot. Mesmerising.

Tusiata’s cousin and current Burns Fellow, Victor Rodger, gave a terrific speech that included a potted biography. I loved the way he applauded Tusiata not just as a tremendous poet, but as a teacher and solo mother. Her names means artist in Samoan and he saw artist in the numerous roles Tusiata embodies. Writing comes out of so much. He identified her new poems as brave, startling, moving and political. Spiky. I totally agree.

Having dedicated her book to her parents, Tusiata said that it was hard to be the parent of a poet who wrote about family. When she told her mother what she was writing, her mother embraced it. She opened her arms wide. She said the skeletons need to come out. The atua. Tusiata’s speech underlined how important this book is. It is not simply an exercise in how you can play with language, it goes to the roots of that it means to be daughter, mother, poet. It goes further than family into what it means to exist, to co-exist, in a global family. When a poet knows how to write what matters so much to her, when her words bring that alive with a such animation, poise and melody, it matters to you.

Four poems read. Lyrical, song-like, chant-like, that place feet on ground, that open the windows to let atua in and out, that cannot turn a blind eye, that hold tight to the love of a daughter, that come back to the body that is pulsing with life.

Yes I had goose bumps. You could hear a pin drop.

Fergus Barrowman, VUP publisher, made the important point that these poems face the dark but they also face an insistent life force.

Congratulations, this was a goosebump launch for a goosebump book.

Hera Lindsay Bird’s debut book broke me apart, gushed oceans of reaction through me and quite simply filled me with the joy of poetry. This is what I posted earlier on the blog:

All I care about is looking at things and naming them’

‘I love life’

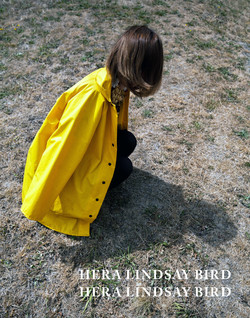

Hera Lindsay Bird Hera Lindsay Bird, Victoria University Press, 2016

For the past week or so, after visits to our key research libraries, I have been writing about Jessie Mackay, a founding mother of New Zealand poetry. What I am writing is under wraps but my relationship with both the woman and her poetry is not clear cut. She moves me, she astonishes me, she irritates me, but I am always filled with admiration. One question bubbling away is: how different is it for women writing over a hundred years later? Sure, contemporary poems are like a foreign country, we have changed so much. But what of our behaviour as poets? Our reception? What feeds us? What renders us vulnerable and what makes us strong?

I want to draw a pencil line from Jessie Mackay to Hera Lindsay Bird and see what I can peg on it. But I want to save these thoughts for my book.

Hera Lindsay Bird has attracted the biggest hoo-ha with a poetry book I can recall. It felt like I was witnessing the birth of a cult object. Images of the book cover on the side of a bus or a building (photoshopped?!?!) created a little Twitter buzz. Lorde tweeted. Anika Moa tweeted. Tim Upperton reviewed it on launch day on National Radio. Interviews flamed the fan base on The Spin Off, The Wireless and Pantograph Punch. The interviews promoted a debut poet that is hip and hot and essential reading. Poems posted have attracted long comment trails that apparently included downright vitriol (I haven’t read these and I think just applied to one poem). The Spin Off cites this as one of a number of factors in the shutting down of all comments on their site. The launch was jam packed, the book sold out, and took the number one spot on the bestseller list. Hera is a poet with attitude. Well, all poets have attitude, but there is a degree of provocation in what she says and writes. Maybe it’s a mix of bite and daring and vulnerability. Just like it is with JM, Hera’s poetry moves, astonishes and irritates me, but most importantly, it gets me thinking/feeling/reacting and prompts admiration.

A few thoughts on Hera Lindsay Bird by Hera Lindsay Bird (VUP author page)

This book is like rebooting self. Each poem reloads Hera. Click click whirr.

At first you might think the book is like the mohawk of a rebellious punk who doesn’t mind hate or kicking stones at glass windows or saying fuck at the drop of a hat.

The word love is in at least two thirds of the poems. It catches you at times with the most surprising, perfect image:

‘when we first fell in love

the heart like a trick candle

on an ancient, moss-dark birthday cake’

‘it’s love that plummets you

back down the elevator shaft’

You could think of this book as a handbook to love because Hera doesn’t just write love poems, she riffs on notions of love:

‘It’s like falling in love for the first time for the last time’

or: ‘What is there to say about love that hasn’t already been’

Some lines are meant to shock you out of reading lethargy:

‘I feel a lot of hate for people’

or: ‘My friend says it’s bad poetry to write a book’

or: ‘Some people are meant to hate forever’

or:

‘It’s a bad crime to say poetry in poetry

It’s a bad, adorable crime

Like robbing a bank with a mini-hairdryer’

Hera reads other poets and uses them as springboards to write from: Mary Ruefle, Bernadette Mayer, Mary Oliver, Chelsey Minnis, Emily Dickinson.

Sometimes the book feels like a confessional board. Poetry as confession. It hurts. There is pain. There is always love.

This poetry is personal. Poems (like little characters) interrupt the personal or the chantlike list or the nettle opinion the honey opinion as though they want a say and need to reflect back on their own making, if not maker.

Love hate sex girlfriends life death: it is not what you write but how you write it that makes a difference, that is the flash in the pan, not to mention the pan itself.

Hera writes in a conversational tone, sometimes loud, sometimes quiet, as though we are in a cafe together and some things get drowned out but the words are electric and we all listen spellbound.

She uses excellent similes. On poetry:

‘This is like an encore to an empty auditorium

It’s a swarm of hornets rising out of the piano’

‘Neither our love nor our failures will save us

all our memories

like tin cans on a wedding car

throwing up sparks’

‘I can only look at you

Like you are a slow-burning planet

And I am pouring water through a telescope.’

Hera likes to talk about bad poems; like the wry punk attitude that says look at my bad style. I am not convinced that there is much in the way of bad poetry here unless you are talking about a vein of impoliteness. It kind of feels like a set of Russian dolls – inside the bad poetry good poetry and inside that the bad and then good and so on and so forth. There is always craft and the ears have been working without fail.

One favourite poem in the book is ‘Mirror Traps’ but I am saving that for the Jessie Mackay pencil line.

Hera’s sumptuous book comes out of a very long tradition of poets busting apart poetic decorum, ideals and displays of self. It’s a while since we have witnessed such provocation on our local poetry scene. What I like about this scintillating writing is that each poem manifests such a love of and agility with words — no matter how bad it tries to be. It is addictive reading. Yes there is a flash that half blinds you and spits searing fat along your forearms, but you get to taste the sizzling halloumi with peppery rocket and citrus dressing.

‘I love to feel this bad because it reminds me of being human

I love this life too

Every day something new happens and I think

so this the way things are now’

PS I adore the cover!

Hera Lindsay Bird has an MA in poetry from Victoria University where she won the 2011 Adam Prize for best folio. She was the 2009 winner of the Story! Inc. Prize for Poetry and the Maurice Gee Prize in Children’s Writing. She lives in Wellington with her girlfriend and collection of Agatha Christie video games.

In a spooky moment of synchronicity, I was walking along Bethells Beach this morning in the crisp gloom hoping Gregory Kan’s book made the shortlist, not realising the decision was out today. I loved the inventiveness, the heart, the attentiveness, the thrilling electricity of his language and so much more:

Gregory Kan This Paper Boat Auckland University Press 2016 (AUP author page)

Gregory Kan’s debut poetry collection, This Paper Boat, is a joy to read on so many levels.

Kan’s poetry has featured in a number of literary journals and an early version of the book was shortlisted for the Kathleen Grattan Poetry Prize in 2013. He lives in Auckland.

Paper Boat traces ghosts. We hold onto Kan’s coat tails as he tracks family and the spirit of poet, Robin Hyde (Iris Wilkinson). The gateway to family becomes the gateway to Iris and the gateway to Iris becomes the gateway to family. There is overlap between family and missing poet but there is also a deep channel. The channel of difficulty, hard knocks, the tough to decipher. There is the creek of foreignness. The abrasiveness of the world when the world is not singular.

Kan enters the thicket of memory as he sets out to recover the family stories. He shows the father as son fishing in the drains, the mother as daughter obedient at school. Yet while he fills his pockets with parental anecdotes, there is too, the poignant way his parents remain other, mysterious, a gap that can never be completely filled:

In the past when I thought about people my parents

were somehow

not among them. But some wound stayed

wide in all of us, and now I see in their faces

strange rivers and waterfalls, tilted over with broom.

The familial stands are immensely moving, but so too is the search for Iris. Kan untangles Iris in the traces she has left – in her poems, her writings, her letters. He stands outside the gate to Wellington house, listening hard, or beside the rock pool. There is something that sets hairs on end when you stand in the footsteps of ghosts, the exact stone, the exact spot, and at times it is though they become both audible and visible. Hyde’s poems in Houses by the Sea, are sumptuous in detail. I think of this as Kan muses on the rock-pool bounty. When he stands at her gate:

I have to hear you to keep you

here, and I have to keep you

here to keep coming back.

I think too of Michele Leggott’s plea at the back of DIA to listen hard to the lost matrix of women poets, the early poets. To find ways to bring them close.

Kan brings Iris (Robin) close. His traces. Iris becomes woman as much as she does poet and the channel of difficulty fills with her darknesses as much as it does Kan’s. There is an aching core of confinement: her pregnancy, her loss of the baby, her second pregnancy, her placement of the baby elsewhere, her mental illness. His confinement in a jungle. His great-aunt’s abandonment as a baby.

The strands of love, foreignness and of difficulty are amplified by the look of the book. The way you aren’t reading a singular river of text that conforms to some kind of pattern. A singular narrative. It is like static, like hiccups, like stutters across the width of reading. I love this. Forms change. Forms make much of the white space. A page looks beautiful, but the white space becomes a transmission point for the voices barely heard.

At one point the blocks of text resemble the silhouettes of photographs in a family album. At another point, poems masquerade as censored Facebook entries.Later still, a fable-like poem tumbles across pages in italics.

The writing is understated, graceful, fluent, visually alive.

I want to pick up Hyde again. I want to stand by that Wellington rock pool and see what I can hear. I have read this book three times and it won’t be the last.

In the final pages, as part a ritual for The Hungry Ghost Festival, Kan sends a paper boat down the river ‘to ensure// that the ghosts find their way/ back.’

The book with its heartfelt offerings is like a paper boat, floating on an ethereal current so that poetry finds its way back to us all (or Hyde, or family).

Auckland University Press page

A terrific interview with Sarah Jane Barnett

Sequence in Sport

Finally Andrew Johnston’s book caught me in a prolonged trance of reading. This from my SST review:

Andrew Johnston, Fits & Starts Victoria University Press (VUP author page)

Based in Paris, Andrew Johnston writes poetry with such grace, and directs his finely-tuned ear and eye to the world and all its marvels. The poems in his new collection, Fits& Starts, luxuriate in white space and they are all the better for it. You want to savour each set of couplets slowly.

The middle section filters Echo through the chapters of the Bible’s First Testament; the final section runs from Alpha through to Zulu and forms an alphabet of exquisite side tracks. With Echo coasting through the sequences, it is not surprising rhyme catches the deftness of Bill Manhire.

Ideas drift like little balloons in and out of poems, experience lies in gritty grains. What is off-real jolts what is real. A taste: ‘How I married distance/ and how close we are.’

This book replays the pulse of living, dream, myth. I am buying it for a poet friend.

This is an urgent, politicised collection, which finds eloquent ways to dramatise and speak out against horrors, injustices and abuses, both domestic and public. The poems are tough, sensuous, often unnerving. Prose poems, pantoums, short lyrics, list poems, hieratic invocations: the passionate voice holds all these together. We teleport between geographies and cultures, Samoa to Christchurch, Gaza to New York. The world we think we know is constantly made strange, yet disconcertingly familiar; the unfamiliar seems normal, close to home.

The twisty, aphoristic, wrong-footing poems in this striking debut collection play the deliberately crass off against the deliberately ornate: ‘Byron, Whitman, our dog crushed by a garage door / Finger me slowly / In the snowscape of your childhood’. Similes, once a poetic no-no, perform exuberant oxymorons and flamboyant non-sequiturs: ‘I write this poem like double-leopard print / Like an antique locket filled with pubic hair’. Bird’s poems readjust readers’ expectations of what poetry can do, how it might behave.

As the marvellously titled opening poem, ‘The Otorhinolaryngologist’, puts it, these poems ‘hunt[] for something / in the hollow spaces // in the voiceless spaces’. These spaces include: found material from ancestry.com, the thoughts of an Afghani, the books of the Old Testament, the myth of Echo, the radio alphabet. The reader is trusted to puzzle, to fit, to start all over again. This hugely impressive, challenging collection is scored through with a broken music that sings in the head.

This ambitious debut collection is built around slivers of life-narrative, principally drawn from the life of Iris Wilkinson (Robin Hyde) and — with moving laconic restraint — from the lives of the poet’s parents, before and after coming to New Zealand. These strands are made to intertwine with, and haunt, each other, not least through the evocation of various Chinese ghosts. The collection aches with bewildered loss, a sense of emotional loose ends and pasts only half-grasped.

Michael Harlow is, with Emma Neale, judging this year’s National Flash Fiction Day (NFFD) competition. We are grateful to him for the time he has put into guest editing this issue, and we look forward to the shared insights of the Harlow-Neale team this year at NFFD.

Michelle Elvy: How fascinating working through the stories this month with you, Michael. I found myself reading at first on my own, with my own individual gaze, and then reading again once I had your feedback to consider as well. Tell me, when you first encountered the short list of 55, what were your early impressions and how did you go about your own initial assessments?

Michael Harlow: In judging or adjudicating the short form or ‘flash’ form, for me it’s always about bringing to the reading a curiosity about what am I going to discover?, which helps to read not only what’s going on at surface level, but also what might be going on between-the-lines, as it were, or at a deeper level. This is possible if one brings to it an ‘informed alertness’. One can’t read, with the right regard, poems or short prose texts if one is thinking about one’s shopping list…

Initially, I’m looking and listening to the language and its music. The text’s words and images; metaphors or word-symbols, or any mythic references. I tend to read all of the submissions aloud at some point; and I’m always listening for how the language goes beyond mere recording of an experience (actual or imaginal) into the feeling area – what is the language saying or trying to express in terms of what the poem feels like – the emotional colour, if you like, of all the language doing its stuff. And then, how is this conveyed or suggested to the reader. So, I’m not really for quite a while so interested in what the text is going to ‘mean’ – the meaning, if it is there or even elusively there, will emerge out of how the language and its thoughtfulness is composed. Every word has a long and deep history, so it makes good sense to read the words (and their translation into images) first, and see what you discover (or you don’t). And I try to keep an eye and ear on discovery as distinct from mere invention (tho imaginative invention is useful indeed). It is this kind of poem, although there are always going to be exceptions, that I short-list for further readings, and in this case, in discussion with my co-judge. And one has to be always alert for the unexpected or the quick surprise that can stretch (or even turn around) one’s prescriptive sense… Taking a collaborative approach – a co-reader-judge – is just very valuable indeed; and more democratic too.

ME: For me, reading your comments helped solidify some of my own early responses, but on the other hand I also found myself thinking harder on the merits or pitfalls of a particular story, so as to engage in a meaningful discussion. Beyond content, reading as an editor involves examining story structure, dialogue, pacing and polish. For me, a story may stand out for its originality, despite some weaknesses. And discussing each of the 55 short-listed stories really brought strengths and weaknesses into focus.

MH: Your response is spot-on, and says a great deal of what I could say, and more; and says it well, too (thanks). I can at this point only add that your editorial approach to reading the particulars – the consideration of the various elements of language being used, and the grammar of thought have been very helpful indeed, and have kept me super alert to the more formal structures that are so important, particularly in the short-form storytelling. Again, the value of a collaborative approach. And your ‘informed alertness’ that you bring to the process can and will inspire confidence in the writer.

ME: We had a number of strong submissions that leaned toward prose poetry, and some you noted for their tone-poem quality. I wonder if you could discuss the line between story and poem, and the importance of sound in writing, with regard to a few of those?

MH: As a reader (and practitioner) I am always aware of the prose that is in poetry, and the poetry that is in the short-prose form – one of the distinctive markers of the prose-poem. In this short form is a coming together of the sentence, which drives the narrative; and the line in poetry, which contains it. Bringing them together in the same field or space is one of the fundamental ways that the prose-poem creates a kind of dynamic tension that suits the short form. I often think of it as a visual model, that of a cruciform: the narrative aspect of the sentence moving along a horizontal line; and the poem line in rather a vertical movement, a kind of wonderfully composed constraint – which makes images, for example, more heightened, and animated, and that carry much of the search for some kind meaning the text might be struggling with and/or leading to…. This is perhaps a little too technical for this kind of project response, and is being developed in an essay I’m composing about flash.

We did have a number of what I think of as tone-poems, which as a form has been around since the beginning of musical (and poetry) composition. When I think of the tone-poem I am thinking of the music that is an inherent possibility in all language. And how the music of the language – its colour, emotional attitude and expressiveness, its lyric reach – can convey meaning. In many ways, then, it’s the sound-of-sense at work in the text. It is the phonic or sound-sense of the language, which is so important especially in the tone-poem to convey some of the feeling aspect, that breathes life into the text.

ME: We had wonderful variety in terms of story contents this month; remnants has proven to be a rich theme. Did the strongest stories strike you for the way they went about tackling the theme, or because of imagery and poeticisms, or clarity of language, or something else entirely? And let’s also talk about ‘making strange’!

MH: The remnants theme was always at the back of my mind as kind of sideline ‘referee’, since it was and is quite a broad theme, with plenty of room for variety of interpretation. Foremost, I was looking for and listening for how the language – its clarity, its aliveness in its imagery and metaphoric reach, and its sound-of-sense – engages the imagination in looking for ways to convey how it is we are so mysterious to ourselves and others… Which leads into ’making strange’ – an extension of which is discovering the strangeness that is in the familiar. By ‘strangeness’ I don’t mean the over-cooked quixotic, or the surrealism of the automatic writing project of some of the early Surrealists, or the contrived hyper-fantastical (that’s for another genre of writing). Rather: I am talking about trusting the unconscious, which is after all a major source of the imagination and the individual curves of the imagination – to make visible the often strange underworld of language. This can and does, if one listens for and to it, exploit the natural associative fluency that is the way the imagination works. All artists/writers/composers know that one is never in complete control of what we are doing when we are creating. The phrase itself (making strange) was at the centre of the Russian Formalist project, and at the core of the early beginnings of the poème en prose in the work of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Mallarmé, et al. Which suggests that this form was in fact a significant contribution to, if not the beginning of, the development of Modernism. What looks rather like an historical digression here is by way of locating the legacy, if you like, passed on to us as writers working in the short-prose/prose-poem form.

ME: It was so interesting to see that one of the stories selected is written by a 15-year-old writer. I am encouraged by young writers delving into the short short form – and as you know we have a youth category in this year’s NFFD competition (judged by Fleur Beale and Heather McQuillan). Do you think the practice of editing down to the essence of a thing is important for new or young writers? And do you think it harder than it seems?

MH: I like your attention to ‘youth writing’, good one. It’s very important to encourage and sometimes even nurture, by way of editorial/editing feedback for all or any of the reasons we might think of. I also think that one shouldn’t overdo it. Slashing away with the ‘red pencil’ too enthusiastically can produce a counter-effect often, in that it can be too devastating to the beginning writer – overkill syndrome. It was quite helpful in our collaboration that you cared so much about this, and that you were so ‘spot on’ in your reading comments. Better I think being selective rather than too inclusive. Editing a manuscript by request is another matter. Young writers can benefit from good editing skills in a number of other writing forums… I’m being a bit long-winded here, so you may need to exercise some of your very fine editing skills!

ME: We often say small fictions have a way of capturing a small moment, a thing that rests there at the surface, or on the page, with other layers happening underneath or at the edges. And yet sometimes a 250- or 300-word story can span a lifetime.

MH: What you say here…’capturing a small moment…with other layers happening underneath…can span a lifetime…’ needs repeating as often as you get the opportunity, because it identifies something of what is at the heart of the form; and it’s very incisive, and insightful of you. How the small, the miniature can contain the large or bigger and the more expansive. Not only Blake’s realization, but at the very heart of the scientific project in quantum physics, and the general search for the building blocks of matter – which is in many ways a search for the exemplary creation story (!). And what can be more important than our own Creation Story? An image that has stayed with me for a long time: looking into a pocket mirror and realizing that it contains the whole of the (Bath) Cathedral, viewed over my shoulder and behind me. A ‘small’ astonishment…

ME: One of the things I enjoy about reading for Flash Frontier is selecting a set of stories that work both individually and as a whole – as a collection. The rewarding challenge, for me as an editor, is finding the hidden gems and helping them shine. Reading for a competition, in contrast, requires a different kind of focus: there is no room for story edits, for re-thinks, for subtle tweaks or rearranged ending phrases. And so, a much harder place for the reader/ judge, because in the end there is less room to be forgiving (and encouraging) to writers. With that in mind, I wonder if you can share some thoughts about what you will be looking for in the flash fictions you read for the 2017 NFFD competition: pitfalls that may disqualify a story, or strengths that may make another stand out?

MH: I think I’ve covered much of this to a large extent in my above comments. I’ll be looking for and listening for much the same kind of stuff that I looked for in individual texts for Flash Frontier. My focus will generally be the same, since by the nature of the exercise, ‘editing’ doesn’t come into it, as you suggest. That said, I generally like to say something in the judge’s comments about the final choices – an indication, however brief, about what I admired and respected.

Emma Neale is, with Michael Harlow, judging this year’s National Flash Fiction Day competition. This month, we talked with her about poetry and prose, ‘glimpses’ and ‘flickers’ and compressed moments. We are delighted to hear some of her insights into reading and writing short forms of varying kinds. We hope you enjoy this interview as much as we have.

Emma Neale: I think the first time I was aware of the possibilities of very short fiction was when I read Virginia Woolf’s selected stories, which she calls ‘wild outbursts of freedom’ – I love the sense of these glancing, shivering rays of prose that reach for something beyond themselves. As the critic Sandra Kemp says, ‘Each moment flickers towards another’ – and Woolf herself described some of ‘these little pieces’ as arriving ‘all in a flash, as if flying, after being kept stone breaking for months.’ There are obvious links to Katherine Mansfield, there, and her ‘glimpses’. Although most of Mansfield’s stories are longer than the flash parameters, some of the fragments in The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks, or her Collected Letters, I think could be called flash fiction – they’re such evocative capsules of sensory and psychological observation that it feels as if, were they to run on for any longer, they would dilute their own potency.

Other writers of flash fiction, who might not call their short works ‘flash’, but whose I’ve really loved, are Charles Simic, Janet Frame, Jayne Anne Phillips, and Frankie McMillan. Simic’s book Dime Store Alchemy : The Art of Joseph Cornell includes work you could also call prose poetry, or even ‘flash biography’, or ‘flash bio-fiction’ – or flash ekphrastics. Or flash bio fictive ekphrasis? So small, so capacious. He uses Joseph Connell’s shadow boxes as starting points for his own surreal prose reveries that float up from the art works – almost as if Cornell’s boxes have released their own dreamy speech bubbles, with Simic as their amanuensis. I love the fabular touch in Simic’s work; he’s a kind of poetry inheritor of Grimm’s fairy tales, I think.

There are several Janet Frame short short stories that could slip into the ‘flash’ holding pen; and I love the way her work is so grounded in a piercingly observed social realism but then often gives a devastating cry into metaphysics, abstraction, a dark, analytical shock at the end. It’s as if she has altered the ‘twist in the tail’ tale so that it’s not a plot revelation she gives us, but a sudden ripping away of the veil of social pretense and practices into, often, the terrifying truth of mortality.

Jayne Anne Phillips is another intriguing flash fiction writer; frequently she explores the power dynamics, distortions and delusions of desire/sexuality in her very short work – and I love the strange, compressed, often overheated imagery she uses.

I had the wonderful experience of editing Frankie McMillan’s My Mother and the Hungarians last year – the first time I’d edited an interlinked series of flash fiction like this. I was completely engaged and transported by the way she managed to make each flash fiction cup its own mood, and yet also managed to carry them all successfully stacked on the narrative’s tray. There is a gentle combination of comedy and sympathy in the work that I think is an extraordinary tonal achievement.

EN:Compression is often called the main shared characteristic – although as soon as I recall that, I think of works like Paradise Lost, and the air goes out of that conviction. Woolf pointed out in her own work that her short fiction had more ‘rhythm’ than ‘narrative’ – so any rigid definition gets into trouble, I think, because every writer treats the form slightly differently. One might work hard to elevate plot as the main attraction of a flash piece; another might want to evoke atmosphere or character.

When I try to write poems, I’m trying to use sonic elements as the main distinguishing characteristic that would separate them from prose. So that means using the line break as evocative pause/silence/breath; assonance; alliteration; rhythm; rhyme and partial rhyme – although I very rarely use strict traditional metrical patterns and end rhymes combined.

We couldn’t cry about love because you just have to get on with it and of course there were the children.

EN: The poems tend to begin with the music or cadence of a particular phrase, although not always. Sometimes they do begin with an image that either troubles me or lifts me in some way. I write more prose poems than I do short stories; and in these, atmosphere is more important than narrative. The ‘how’ is more interesting than the ‘what’, in other words. In my novels, however, the dynamics between people and the question ‘what if?’ work together to feed a longer meditation on how characters get themselves in and out of various psychological predicaments.

EN: I think I learned this mainly from reading Mansfield and Frame during my PhD study. Their use of sensory image and metaphor taught me to look up at the world around me and try to convey how it presses against mind and skin. It’s also been a pragmatic response to juggling parenthood with work and writing. I haven’t had the time or resources to research grand historical or social movements; I’ve had to, increasingly, seize moments on the run. Although, that said, each novel I write has involved some research – just not the years and years in archives that I fantasise I might have had if I – well, let’s be realistic – if I were a completely different, less shambolic and more patient person.

EN: I started when I was very young and can still remember my first lesson in lineation from my primary school teacher; I was fascinated by the rule that a line that ran on too long for the right margin had to be stepped under itself. For some reason I found that urgent and thrilling. Before that, though, my mother had read poetry to me regularly – strong rhythmic expressive work like AA Milne’s poems for children, nursery rhymes and so on – and I never lost the habit of foraging bookshelves for more poetry. I kept a commonplace book from the age of about 11 or 12; I wrote in my spare time as a teenager, and started buying books of poetry for myself probably from about 15.

Major influences are hard to enumerate because I think unconscious influences are probably just as strong as writers I’ve fallen for and would instantly name. But – in terms of obvious education – I studied modern poetry at Victoria University of Wellington, and loved writing about Plath, Hughes, Larkin, Heaney; I tried to read everything by Bill Manhire, who was a lecturer of mine in both literary history and creative writing; I loved work by all kinds of New Zealand poets – Hone Tuwhare, Michael Harlow, Cilla McQueen, Ruth Dallas, Lauris Edmond, David Eggleton, Anne Kennedy, Paula Green, Vincent O’Sullivan, Jenny Bornholdt, Andrew Johnston, Paola Bilbrough – yet listing seems both reductive (there are many others), and also slightly misleading, as it’s often particular poems rather than entire bibliographies that have stayed resonant for me. I had very influential letters and sharp words from writing age-peers of mine when I was in my 20s; certain comments cut me to the core, as they really only can when you’re young — but I think they did help me both to develop an internal quality control and also a stubborn decision to carry on certain quirks. I’ve been through obsessive reading phases of poets like Louis MacNiece, Emily Dickinson, Elizabeth Bishop, Wallace Stevens, Louise Glück, Charles Simic, Anne Carson, Jack Gilbert, Pascale Petit, Robert Hayden, Anne Hébert and others, none of whom I think I can write anything like – but I also think that we read to take us away from ourselves and our internal soundtracks. So tracing influences is very unscientific. I try to stay open to poetry by younger writers now too: Warsan Shire, Alvin Pang, Joan Fleming, Kate Tempest, Jack Underwood, Emily Berry, Lemn Sissay – although I read in such a fragmented, often unscholarly way now, that I don’t know if anyone can really replace the deep and unconscious influence of the early poets I discovered when 30 and under.

He knows she can’t reply. The cell phone in his hand fits like an amulet, a locket that could show a rare old photo of the dead: delicate gold hinges only turned open when he’s alone. He keys in her name, a phrase, deletes. He’s under a kowhai whose yellow flowers hang down as if a woman tents him in her sleepy hair. Six tui tilt and tip in black arabesques fold the air with a crêpe paper rustle. He closes his eyes against vertigo, presses the bark that runs rough as unhealed grazes; imagines a room maple-coloured like a ship’s cabin and another man who hears her breath as if she is a child crouched in a wardrobe waiting for the dark’s hard sounds to resolve into words. He enters her name again. His thumb tingles as if the keypad were a cool metal zip lifted from the hollow in a neck, wooden toggles slipped from their soft cotton locks. He imagines the back of her head, the stitches of her collar, the fibres that sundust an earlobe. Ridiculous human thing, he types in another line of evidence, again deletes it. Buttons his coat right up to his throat as if to head somewhere colder: the wharf, say; oil-scummed water; salt-sting squall; a place to gather a fist of gravel as if everything launched and left to sink is simple boyish sport. The tuis’ coal-smoke ballet ignites to black shimmer: banks, plummets, surges higher. He slips the phone back into his pocket where he holds it like a smaller hand he must warm, holds it fingers tipped on its skin as if to a mouth: Let’s not say anything more, now.

EN: It all comes down to sound. Although this poem doesn’t have a regular stanzaic arrangement, the things that distinguish it from prose to me are the placement of the line-break; the notation of silence at line ends and stanza ends; the sonic emphasis on prosody, even if a traditionalist would only hear trace elements of that. I think if you read that poem aloud, you’ll hear how the line break helps to increase the stress on certain sounds.

EN: This is a very tough one to answer briefly as Billy Bird started as a verse novel, and then broke out of that cage and became a novel speckled with different aspects of poetry. Cheekily, I’ll refer you there to an interview I did with Sarah Jane Barnett at The Pantograph Punch. At least that’s an honest repetition, rather than self-plagiarism.

EN: I’m looking forward to something piquant, with unexpected yet apt tonal or narrative shifts. I’ll be fossicking for startling imagery married with a kind of forward motion – although I’m also looking forward to seeing how many writers go for narrative, and how many go for atmosphere or character instead. I want to see how many different ways writers flex the form. My advice would be to ask yourself if the imagery you’ve chosen is doing more than just prettifying the story: is it also carrying the right psychological load for the piece? The other is to imagine the story read aloud. Even with this word limit, would it bore your neighbour on a bus ride downtown? Or would it leave them wishing they didn’t have to leap off at their destination?

Thank you, Emma Neale. Here’s to the 2017 NFFD competition. Writers, get writing!

This year, National Flash Fiction Day has added a Youth (18 and under) category to the competition. We are excited to see more young people experimenting with the compressed form, and we welcome award-winning YA novelist Fleur Beale and the 2016 NFFD winner Heather McQuillan as judges of this new competition.

To the youth of Aotearoa: Get flashing!

Fleur Beale: Draft and redraft. Take out any words that aren’t essential. Keep the story compact, i.e., only one or two characters, one setting and one happening. Embrace the unexpected.

Heather McQuillan: I absolutely agree with Fleur. Writing short requires lots of changing and rearranging to get right.

You also have to tell your story in the best words possible. When you redraft make sure that nouns are specific and verbs are lively. Adjectives must earn their place and adverbs are redundant. Arrange those best words into well-constructed sentences and read them over and over to check for meaning, flow and effect.

HM: Even though you only have a few words you have to write a story that the reader can understand. Too often I’ve read (and written) stories that leave far too of the work much up to the poor reader. It’s a careful balance: too obvious is no fun and too cryptic is frustrating. They may be wondering along the way but at the end they have to be able to say, “Aha! So this is what it makes me think” rather than “What the heck was that all about?” Consider your reader.

The other common problem I’ve seen from young writers is trying to squish too much in. You need to think of this as a scene, maybe two very short scenes, not the whole movie. In this instance you don’t need a beginning; jump right in. But you do need something interesting to happen and you do need to bring about a change or shift, either for your character or your reader – or, hopefully, both.

HM: Flash fiction does not have a set formula – just take a look at some online journals! There you will see a range of tone, of stance, of style, of genre, of theme, of topic. I

suggest that you ask at your local or school library for ReDraft: Winning Writing by New Zealand Teenagers (the 2016 edition is titled The Dog Upstairs) or Write On magazine (the latest edition with the Tetris cover has a flash fiction feature), or look online at fingers comma toes to get an idea of what great writing by young people looks like.

But remember, we want to hear your voice, your take on what flash fiction can be.

FB: I’m hanging out to get hold of Maurice Gee’s latest, The Severed Land. Am also very excited that my niece Juliet Jacka’s next two books in her Frankie Pots girl detective series are out. They are for a mid-grade audience and so much fun.

HM: Like Fleur, I’m awaiting the arrival of my copy of The Severed Land by Maurice Gee. It’s in the mail. I also read today that Philip Pullman has a new trilogy, The Book of Dust, which crosses over with his Dark Materials series and I actually did a tiny dance of nerdy excitement. I do love great fantasy and science and speculative fiction!

FB: I suspect I’m going to get very hooked on flash fiction…

HM: I’m waiting for a letter from a publisher that tells me they have accepted the YA novel I finished last year. It is all about how unfair life can be, particularly when an evil corporation runs both schools and prisons and makes more money per prisoner than per pupil! But it’s mostly about how we should speak up for our friends, for ourselves and for what is right ‘Even if Your Voice Shakes’ (that’s the working title). I hope I don’t have to wait too long for the acceptance letter! I am also partway through a flash/verse novel based on the experience of Filipino migrant teens in post-earthquake Christchurch. My main new project will be a collection of flash fiction stories that will contribute towards a Masters in Creative Writing Thesis. And I will still be tutoring at The School for Young Writers in Christchurch. I love teaching but sometimes the kids write such amazing things they make me envious!

Bill Manhire has two new books out this year – a collection of poetry called Some Things To Place in a Coffin and Tell Me My Name – a collection of riddles along with a CD of songs composed by Norman Meehan, sung by Hannah Griffin.

Bill Manhire founded the International Institute of Modern Letters, which is home to New Zealand’s leading creative writing program. He is now Emeritus Professor of English and Creative Writing at Victoria. In 1997 he was made New Zealand’s inaugural Poet Laureate, and in 2005 he was appointed a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit and in in the same year was named an Arts Foundation of New Zealand Laureate. He holds an honorary Doctorate of Literature from the University of Otago and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand. He received the Prime Minister’s Award for poetry in 2007. In 2016 Victoria University Press published The Stories of Bill Manhire which collected new and published short fiction.

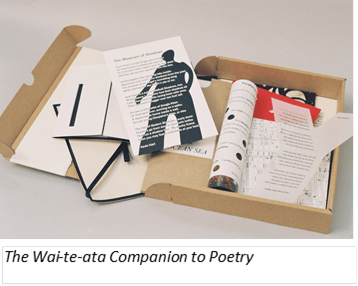

Victoria University of Wellington’s Wai-te-ata Press has been announced as a finalist in the prestigious Manly Artists’ Books Awards, for its artists’ book The Wai-te-ata Companion to Poetry.

An artists’ book is one made by an artist as artwork, and often reinvents the book form and challenges the reading experience.

The award is a biennial prize run by the Manly Public Library, New South Wales, Australia. Winning entries are acquired by the library and entered into specialist artists’ books collections, such as the Australian National Art Gallery collection, which holds more than 1000 artists’ books that date back to the 1970s.

Wellington artist and curator, Paul Thompson, says the success of The Wai-te-ata Companion to Poetry is due to the imagination that has gone into it.

“I had a strong concept for a book, made a mock-up and went to Wai-te-ata Press to see if they were interested in collaboration,” Mr Thompson says.

Dr Sydney Shep, Reader in Book History at Victoria and Director of Wai-te-ata Press says: “We recognised a good idea and have the experience, skills and knowledge to deliver it. The Press is known for its production of both New Zealand poetry and many other high quality and typographically adventurous publications.”

Designer and fellow book artist Glenna Matcham, focused on the opportunity to “bring enthusiasm, design and craft skills to an unusual project”.

“The Wai-te-ata Companion to Poetry is not a book to be judged by its cover,” says Dr Shep.

“The plain brown cardboard box holds 10 poems covering the last 200 years—ranging from well-known classics to poems from contemporary New Zealand and Australian poets. Each poem is treated as a digital handmade object rather than just a nicely designed and printed sheet of paper. Whether a map, a booklet, a cylinder or printed on sandpaper, each poem takes a unique form dictated by the content.”

“In a way it’s like interactive poetry,” says Mr Thompson, “but it works on several levels at the same time. One can read and enjoy the poems or, like any successful work of art, be immersed in an intensive experience of thinking, associating and exploring.”

For more information, and to purchase a limited edition copy, contact:

Dr Sydney Shep on 04-463 5684 or sydney.shep@vuw.ac.nz.

Paul Thompson on 04-913 9045 or museumphoton@clear.net.nz.

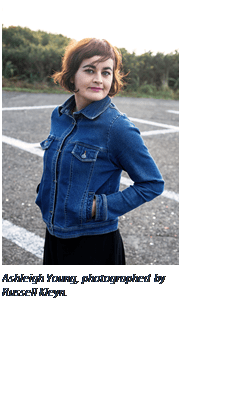

I have already posted this but thought I would do so again in view of Ashleigh’s prestigious writing award from Yale University (Windham-Campbell Prize).

You can hear Ashleigh and Kathryn Ryan in conversation on Radio National at 9.30 this morning.

I loved this book so much – well deserved congratulations, Ashleigh.

Can You Tolerate This? Personal Essays, Ashleigh Young, Victoria University Press, 2016

The other day I was on a plane about to fly to New Plymouth to go to the Ronald Hugh Morrieson Literary Award ceremony in Hawera. It was tight timing. I was going to jump off the plane into a car, drive for an hour, and walk into the function in the nick of time. But the plane’s lights kept switching on and off, the engine sounds rising and falling. It was faint-inducing heat. Babies were screaming, a high pitch of chat drowned out the safety talk. I had Ashleigh Young’s book of essays on my lap to finish on the plane. In my head I shouted, I just want to get off this place. Seconds later as though my wish made it true, we were told the plane had been cancelled and we needed to get another. I was right down the back of the plane and still not up to running in my foot-recovery regime but knew I really really wanted to do my job as judge. So I started running towards the ticket counter, foot alarmed.

I am running like an elephant or our duck-waddle cat. I can hear all these other flights that have been cancelled due to engineering problems. Everyone is running and scrambling and agonising. Three-quarters there and I hear our plane has now switched to delayed. I limp back to the regional cafe and start reading Ashleigh Young to blot out the panic. She is on an aeroplane. She is sitting next to a woman who tells her life story and her life story is extravagant. We hardly know what to trust – and that is what makes it such a gem. I can’t focus though. I can’t pick another story now with my skewy focus so hobble back to the ticket counter and hear all sorts of rumours. Our new plane was the cancelled Taupo plane. Everyone else is being bussed. I keep thinking about the woman with her extravagant stories and it reminded me of an Italian author Gianni Celati who collected the stories of others where the feather line between real and unreal is flighty. I am in the muddlewash of queues when a woman calls out asking if anyone needs special assistance. I ask for a wheelchair. I am being wheeled. I am back on the new plane next to the same young woman. She is studying physiotherapy. I could embroider my life.The fact I even tell her where I am going is like a little character warpslip as usually I don’t say a word on planes. We talk about injuries and homes. I have two of Ashleigh’s stories to go. I don’t get to read them. I walk into the ceremony 40 minutes late.

Asleigh Young’s collection of personal essays is an addictive read, but it is the kind of book I wanted to eek out (I read the last two stories on the plane home!). What would fill the gap? What would deliver the same sustaining mix of wit, revelation and aromatic detail. Ashleigh gathers in stories from her own life and replays them in sentences that flow so sweetly. Each essay is like a musical composition but it is the content that offers the reader gold. I love the shift in perception from child to adult, in reflecting back. I love the way stories harness what is intimate and personal but also venture out into the world, a world filtered through reading and the experiences of others, fascinating or strange. Perhaps it is all to do with a wry and agile mind that likes to roam and fossick.

Here’s a tasting plate of things I loved

Now and then you fall upon the way story comes into being. This one is especially good. It’s in in a terrific essay on her brother, JP:

‘My enthusiasm for the story was such that I felt it would write itself. The story was virtually already made. All I needed to do was grab hold of one end and pull the rest up behind it like an electric wire out of the ground.’ from ‘Big Red’

In the same essay this gem:

‘Just as JP was abandoning fashion, Neil and I were finding it, and fashion equipped us with new ways of being embarrassed.’

Still in the same essay, Ashleigh gets thinking about story again when she thinks about her film-making brother Neil:

‘Write your way towards an understanding, a tutor told me in a creative writing class. But what if you went backwards and wrote yourself away from the understanding?’

This strikes me as the kind of thing a Chinese philosopher might say in that going backwards is in fact your way forwards; in not knowing what you know, in knowing you don’t know.

One of the poems in New York Pocket Book picks up on Frank O’Hara’s accent. I loved reading the Frank O’Hara segue (pp70-71).

‘I returned to his lines over and over.’

Reading Frank’s lines from ‘Adieu to Norman, Bonjour to Joan and Jean-Paul,’ got Ashleigh thinking about continuity:

‘I fixated on these lines because they made me think about ways in which to continue, and what continuing meant. Getting up in the morning was one way. Getting dressed, facing the people around you–these were ways of continuing that kept your life open to possibility. But there was another way of continuing, and this was the continuing of silence. Our family had always continued to continue through events that we did not know how to speak of to one another.’

This from the plane story ‘Window Seat’:

‘I made my mind up to not decide there and then whether she was telling the truth. I wanted to stay open for as long as I could. I was wide awake when she said with resolve, ” Now, I’m going to tell you about you.”‘

I found this story moved me on so many surprising levels. The woman and her extravagant tongue. Especially the portrait of Ashleigh. I was holding the book on a plane and squirming. Squirming too at the way we reveal ourselves in shards that might embarrass. The book made me laugh out loud. Or just smile at that coiling thought. Or the deep-seated warmth of family, whatever the ups and downs. I thought the last essay, ‘Lark,’ an essay in which Ashleigh’s mother is encouraged to write, was the perfect ending. The mother rode her bike alongside them on the way to school, she used jackhammers and stripped paint off furniture. I adored the shadowy overlap between mother and daughter. Here is the gorgeous last paragraph of both book and essay:

‘A wine glass with tidal marks is on the table beside Julia’s father’s desk lamp. The lamp is doubled over like something in pain. From our desk inside the house where we are studying, we can see her through the caravan’s oblong window. Tonight she is at work on the book. She is trying to remember things. It is like practising another sort of language. It leads her to herself and it leads her away. Sometimes it unsteadies her until she finds another small friend to hold on to. A moonish light comes from her window. Her cloudy head bends over the table as she writes.’

This is a fabulous, symphonic collection. Ashleigh dares to imagine as much as she dares to admit. She has no doubt prompted us, from Cape Reinga to Rakiura, to get out pen and paper and write our way backwards, pulling electric cables, making room for extravagant tongues and familial love. I cannot recommend this collection highly enough.

Victoria University Press author page

1 March 2017

___________________________________________________________

Victoria creative writing tutor and alumna awarded prestigious Yale writing prize

Victoria University of Wellington staff member and alumna Ashleigh Young has won a prestigious Windham-Campbell Literature Prize worth USD$165,000 for her book of essays Can You Tolerate This? published by Victoria University Press (VUP) in 2016.

The annual prize is administered by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University and is awarded to writers around the globe to support their writing. Ms Young is one of eight prizewinners this year, and the first New Zealand writer to be awarded the prize since it was established in 2013.

Ms Young, who is a creative writing workshop coordinator at Victoria and an editor for VUP, says when she was first contacted about the prize she thought it was a hoax.

“A few moments after receiving a dubious-looking email, I was speaking to a man named Michael Kelleher, in Yale, Connecticut. He said: ‘So, listen, we’ve all been reading your book.’ It is an incredible thing to hear those words spoken in an American accent. And he said there was this prize called the Windham-Campbell Prize, and the prize was $165,000. And I had won it, for my book of essays.

“By this point I was clutching my head and my knees were giving out. I got off the phone and all my workmates were screaming. There was a lot of screaming that day. I’m actually still screaming right now. Just very quietly.”

The nomination process for the prize is done privately and the phone call from Yale is the first time winners are made aware of their award.

Previous winners of the prize include Helen Garner, Teju Cole, Hilton Als and Tessa Hadley.

Ms Young will receive the prize money in September, when she travels to Windham-Campbell Festival at Yale.

Ms Young says she’s finding it hard to accept that the prize is real.

“I’ve always thought of myself as ‘a small writer’. Someone who could only ever write in the margins, and only ever about her small experiences. But this truly mind-boggling honour means that suddenly, a dreamlike opportunity has opened up in front of me – to bring writing into the heart of my life and to have faith that it’s the right thing. I feel a gratitude that I can’t find words for. The generosity of the prize is completely astounding.”

Can You Tolerate This? is a collection of 21 personal essays with content that ranges from Hamilton’s nineties music scene to a stone-collecting French postman, family histories to Bikram yoga.

Ms Young began the collection during her Master of Arts in Creative Writing at Victoria’s International Institute of Modern Letters, and won the Adam Foundation Prize in Creative Writing for her Master’s manuscript. She has also published a collection of poems, Magnificent Moon (VUP, 2012).

Can You Tolerate This? has also been longlisted for the 2017 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.