Giving Birth to My Father, Tusiata Avia

Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2025

Ah. Tusiata Avia’s sublime fifth poetry collection is like moving into a meditative room where grief and love are yin and yang. The book is written to and from the death of her father, which in Sāmoan culture, is also his birth. Tusiata’s dad had lived in Aotearoa for fifty years, but returned to Sāmoa for the final stages of his life. He had helped build and nurture the Sāmoan community in Ōtautahi Christchurch.

The opening poems rise out of mourning, out of her father’s funeral ceremony in Sāmoa. First an imagined how-it-was-supposed-to-go sequence. Then a second how it-actually-went sequence. This precious collection was nine years in the making; a book, as Tusiata said in an RNZ radio interview, that was difficult to send into the world, a book in which she kept adjusting thoughts feelings revelations. It’s a eulogy, it’s writing poetry as a way of drawing close, it’s poetry as writing the gap that aches, facing the questions that compound, the anger that sizzles, it’s writing and living when each day grief is the shawl draped across the shoulders of being.

Yes. It’s travelling with and responding to and negotiating grief.

Ah. I am so deeply moved as I read this. Entering different scenes. Sometimes poignant, such as ‘In the Countdown carpark’, when the father’s hand rests on the shoulder of his fifty-year-old daughter sitting in his kitchen as she weeps. Or the flashes of anger at Sāmoan funeral culture and the way a grieving family feels, or the presence of water and of boats, the carving of boats, the rowing the steering the sharing. There is the ping and pang that her father wasn’t always present, a voice on the end of the line, and then how father and daughter are moving closer with visits in later years. The way mother and daughter, brother and many aunties, are also moving in and out of scenes, amplifying the love, sometimes irritations, but always returning and maintaining the integral power of alofa.

Yes. It’s travelling with and responding to and transmitting alofa.

It’s recognising the complicated difficulties of being mother daughter sister niece. It’s sitting in the gods with her mother to watch her dad in the band or hearing her beloved daughter on the ukulele.

It is is the shifting lights of here and not here, and as a reader my every pore is trembling. This from ‘I thought you were gone and not coming back’, where there are multiple light sources, there’s ice cream and old women’s foreheads:

It’s important I know where the light is coming from –

the afterlife or the ice cream?

My grandmother’s hair or the minister’s house?

The important thing is: I thought you were gone.

And then to read the final skin-trembling line: “in other words, you are the light, Dad.”

I stall on the poem, ‘Watch’. This is what Tusiata’s poetry can do. Swivel and tilt you as each poem carries you though every diamond-cut facet of feeling. Heck this poem sticks to me as it unfolds. The poet, and yes I am saying Tusiata, because this collection is incredibly personal, removes the watch from her father’s wrist, and then places it upon her own. You get that skin tremble again with building memory-ache as both poet and wristwatch summon this place and that occasion, this smell and that nickname. The brown watch that becomes gold watch, becomes missing watch, that becomes this watch returned. It’s me brimming with alofa and grief and tenderness, especially when I read the final two stanzas:

That was six months ago. Now I’m in the Sky City Hotel layering

myself in my niece’s make-up. I am going to have a seizure in a few

minutes. I will wake up and find myself on the bathroom floor. I

will crawl to the hotel phone, ring my cousin in Christchurch and

ask her what city I’m in and what to do.

You’re at the book awards, the book awards, she calls to me. Ring

Hine and make her come and get you. I ring Hine, who will win

the book awards. Before I leave the room, I open a small zip on the

side of my overnight bag and my father enters the room. He slips

the watch over my wrist. I kiss his hand. And we go.

And here we go, yes let’s go into the meditative room of reading, this special special place that Tusiata has built for herself, for her loved ones, that we, her poetry fans and friends can share, travelling deep into grief and alofa through the power and nourishing strength of words. Thank you.

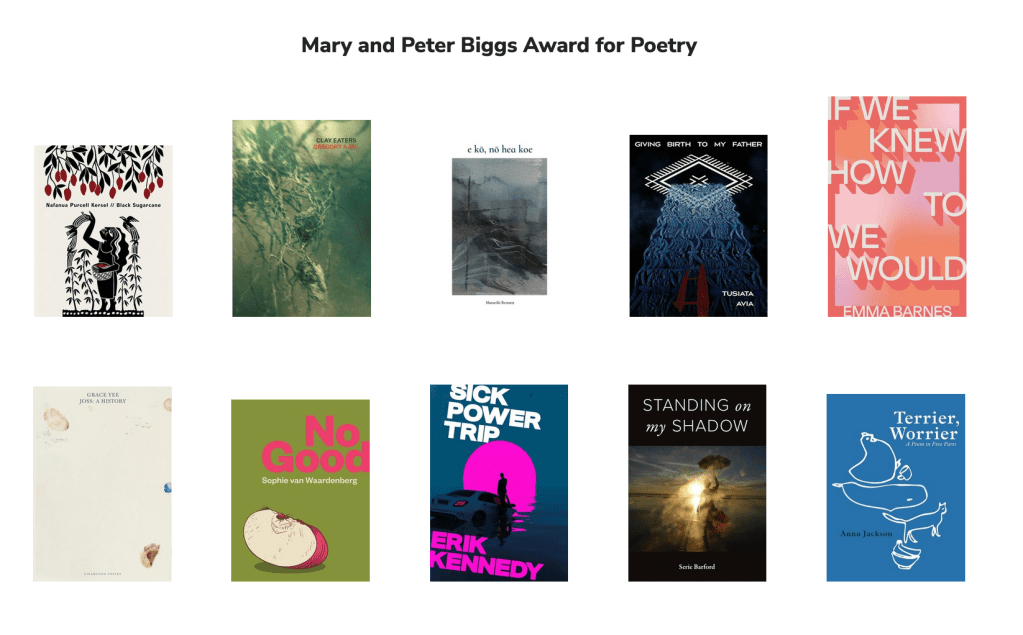

Tusiata Avia is the award-winning author of Wild Dogs Under My Skirt (2004; also staged internationally), Bloodclot (2009), Fale Aitu | Spirit House (2016), The Savage Coloniser Book (2020; winner of the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry and also staged nationally) and Big Fat Brown Bitch (2023). Tusiata has held the Fulbright Pacific Writers Fellowship at the University of Hawai‘i in 2005 and the Ursula Bethell Writer in Residence at University of Canterbury in 2010. She was the 2013 recipient of the Janet Frame Literary Trust Award, and in 2020 was appointed a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to poetry and the arts. In 2023 she was given a Distinguished Alumni Award at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington and a Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement.

Te Herenga Waka University page

Interview on RNZ on Culture 101